Download PDF Excerpt

Videos by Coauthors

Follow us on YouTube

Rights Information

Managers as Mentors 3rd Edition

Building Partnerships for Learning

Chip Bell (Author) | Marshall Goldsmith (Author)

Publication date: 06/03/2013

Bestseller over 135,000+ copies sold

Augmented with six case studies of some of the top US CEOs. New chapters cover topics such as the role of mentoring in spurring innovation.

- New edition of a classic that has sold 120,000 copies worldwide and been translated into 10 languages

- Now coauthored by bestselling business author Marshall Goldsmith

- Completely revised and updated throughout with twelve new chapters, new tools, and new case studies

Mentoring is more important than ever. Younger workers expect it or they'll walk. Organizations need to provide it to stay competitive. This latest edition of the classic Managers as Mentors is a rapid-fire read that guides leaders in helping associates grow and adapt in today's tumultuous organizations. Thoroughly revised and updated, this edition places increased emphasis on the mentor as a learning catalyst for the protégé rather than as someone who simply hands down knowledge-crucial for younger workers who prize growth opportunities but tend to distrust hierarchy.

As with previous editions, a fictional case study of a mentor-protégé relationship runs through the book. But now this is augmented with six case studies of some of the top US CEOs. New chapters cover topics such as the role of mentoring in spurring innovation and mentoring a diverse and dispersed workforce accustomed to interacting and getting information digitally. Also new to this edition is the Mentor's Toolkit, six resources to help in developing the mentor-protégé relationship.

This hands-on guide takes the mystery out of effective mentoring, teaching leaders to be the kind of confident coaches integral to learning organizations.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( [email protected] )

Augmented with six case studies of some of the top US CEOs. New chapters cover topics such as the role of mentoring in spurring innovation.

- New edition of a classic that has sold 120,000 copies worldwide and been translated into 10 languages

- Now coauthored by bestselling business author Marshall Goldsmith

- Completely revised and updated throughout with twelve new chapters, new tools, and new case studies

Mentoring is more important than ever. Younger workers expect it or they'll walk. Organizations need to provide it to stay competitive. This latest edition of the classic Managers as Mentors is a rapid-fire read that guides leaders in helping associates grow and adapt in today's tumultuous organizations. Thoroughly revised and updated, this edition places increased emphasis on the mentor as a learning catalyst for the protégé rather than as someone who simply hands down knowledge-crucial for younger workers who prize growth opportunities but tend to distrust hierarchy.

As with previous editions, a fictional case study of a mentor-protégé relationship runs through the book. But now this is augmented with six case studies of some of the top US CEOs. New chapters cover topics such as the role of mentoring in spurring innovation and mentoring a diverse and dispersed workforce accustomed to interacting and getting information digitally. Also new to this edition is the Mentor's Toolkit, six resources to help in developing the mentor-protégé relationship.

This hands-on guide takes the mystery out of effective mentoring, teaching leaders to be the kind of confident coaches integral to learning organizations.

Chip R. Bell is a renowned keynote speaker and a senior partner with the Chip Bell Group. Global Gurus in 2020 ranked him for the sixth year in a row in the top three keynote speakers in the world on customer service. He has served as a consultant, trainer, or speaker to such major organizations as Ritz-Carlton Hotels, USAA, Harley-Davidson, Marriott, Microsoft, Lockheed-Martin, Cadillac, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Allstate, Caterpillar, Ultimate Software, Accenture, Verizon, and Home Depot. He was a highly decorated infantry unit commander in Vietnam with the elite 82nd Airborne and served as a guerilla tactics instructor with the Army Infantry School.

In 1989, with his co-author Ron Zemke, he pioneered what is now practiced universally as customer journey mapping, writing extensively about it in their 2003 book Service Magic. In 2005, he created the now patented practice of customer forensics.

Chip is the author of twenty-three books, including Kaleidoscope: Delivering Innovative Service That Sparkles (winner of a 2017 Best Book Award), Sprinkles: Creating Awesome Experiences Through Innovative Service, The 9½ Principles of Innovative Service,

Wired and Dangerous

(co-authored with John Patterson and a winner of a 2011 Axiom Award as well as a 2012 Independent Publishers IPPY Award),

Take Their Breath Away

(also with John Patterson),

Magnetic Service

(with Bilijack Bell and winner of the 2004 Benjamin Franklin Award),

Managing Knock Your Socks Off Service

(with Ron Zemke), Managers as Mentors (with Marshall Goldsmith and winner of an Athena Award),

Service Magic

(also with Ron Zemke),

Dance Lessons

(with Heather Shea) and Customers as Partners.

ICMI ranked him in 2019 among the top 10 bloggers on customer care. His “Service Unleashed” training program won a 2018 Stevie Award. He has appeared live on CNN, CNBC, Bloomberg TV, Fox Business, ABC, NPR and his work has appeared in Fortune, Forbes, Entrepreneur, Inc. Magazine, CEO Magazine, Fast Company, Real Leader, USA Today, Success, Wall Street Journal, Money Magazine and Businessweek. He writes a regular column for Forbes, CEO Magazine, CEO World Magazine, Real Leaders, MoneyInc, Retail Customer Experience, Smart Customer Service and SmartBrief on Leadership.

—Mike Krzyzewski, Head Coach, Duke University Men's Basketball, 2010 NCAA Champions

“Mentoring is the highest of the teaching arts, and in this new edition, Chip Bell and Marshall Goldsmith have skillfully crafted the essential handbook for all those who are trusted advisors to aspiring leaders.”

—Jim Kouzes, coauthor of The Leadership Challenge and Dean's Executive Fellow of Leadership, Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University

“Managers as Mentors will be the indispensable handbook of managers/leaders across the sectors.”

—Frances Hesselbein, President and CEO, The Frances Hesselbein Leadership Institute, and former CEO, Girls Scouts of the USA

Beginning Our Journey

Part 1 Mentoring Is . . .

1 Panning for Insight: The Art of Mentoring

2 Mentoring in Action: The Act of Mentoring Up Close

3 Assessing Your Mentoring Talents: A Self-Check Scale

4 CASE STUDY Every Knock's a Boost: An Interview with Mark Tercek, CEO of The Nature Conservancy

Part 2 Surrendering--Leveling the Learning Field

5 Kindling Kinship: The Power of Rapport

6 The Elements of Trust Making: "This Could Be the Start of Something Big!"

7 The Person in the Mirror: Mentor Humility Creates Protégé Confidence

8 Inside the Mind of the Protégé: When Fear and Learning Collide

9 CASE STUDY Fail Faster: An Interview with Liz Smith, CEO of Bloomin' Brands

Part 3 Accepting--Creating a Safe Haven for Risk Taking

10 Invitations to Risk: Acceptance as a Nurturer of Courage

11 Socrates' Great Secret: Awesome Queries

12 The Ear of an Ally: The Lost Art of Listening

13 "Give-and-Take" Starts with "Give": Distinguished Dialogues

14 CASE STUDY Simply Listen: An Interview with Deanna Mulligan, CEO of the Guardian Life Insurance Company of America

Part 4 Gifting--The Main Event

15 Avoiding Thin Ice: The Gift of Advice

16 Reporting on Blind Spots: The Gifts of Feedback and Feedforward

17 Linking Profi ciency to Purpose: The Gift of Focus

18 The Bluebirds' Secret: The Gift of Balance

19 Inviting Your Protégé to Enchantment: The Gift of Story

20 CASE STUDY Grace under Fire: An Interview with Joe Almeida, CEO of Covidien

Part 5 Extending-Nurturing a Self-Directed Learner

21 Beyond the Relationship: Ensuring the Transfer of Learning

22 "If You Want Something to Grow, Pour Champagne on It!"

23 Managing Sweet Sorrow: Life after Mentoring

24 CASE STUDY Fly High, Dive Deep: An Interview with Fred Hassan, Managing Director of Warburg Pincus, LLC

Part 6 Special Conditions

25 Unholy Alliances: Mentoring in Precarious Relationships

26 Arduous Alliances: Mentoring in Precarious Situations

27 CASE STUDY Respect Everyone: An Interview with Frances Hesselbein, CEO of Frances Hesselbein Leadership Institute

Part 7 The Mentor's Toolkit

Tool #1: Quick Tips for Mentors and Protégés

Tool #2: Mentoring Competence Measure

Tool #3: Mentoring FAQs

Tool #4: More Reading on Mentoring

Tool #5. Elements of a Learning Plan

Tool #6: The Eagle: An Inspirational Story

Notes

Bibliography

Thanks

Index

About the Authors

1

Panning for Insight

The Art of Mentoring

Learning is not attained by chance; it must be sought for with ardor and attended to with diligence.

Abigail Adams (1780)

Panning for gold is a lot like mentoring. It is not always easy. Panning for gold works like this. First, you put a double handful of sand in a heavy-gauge steel shallow pan and dip it in the water, filling it half full of water. Next, you gently move the pan back and forth as you let small amounts of yellow sand wash over the side of the pan.

The objective is to let the black sand sink to the bottom of the gold pan. But this is the point where panning for gold gets real serious. Impatience or strong-arming the way the pan is shaken means the black sand escapes over the side along with the yellow sand. Once black sand is the only sand left in the pan, you are rewarded with flecks of gold. The gold resides among the black sand.

Mentoring can be like panning for gold among the sand. Insight is generally not lying on top ready to be found and polished. If it were easy pickings, the help of a mentor would be unnecessary. It lies beneath the obvious and ordinary. It is lodged in the dark sands of irrational beliefs, myths, fears, prejudices, and biases. It lurks under untested hunches, ill-prepared starts, and unfortunate mistakes. Helping the protégé extract insight takes patience and persistence. It cannot be rushed and haphazardly forced. And, most of all, it cannot be strong-armed with the force of the mentor. It must be discovered by the protégé with the guidance of the mentor.

As a mentor, you are in charge of getting the protégé to properly shake the pan. You help the protégé learn to recognize the real treasures of insight and understanding and not be seduced by “fool’s gold”—achieved by rote and temporarily retained only “until the exam is over.” The way you help the protégé handle the dark sand is central to the acquisition of wisdom. That is the essence of mentoring with a partnership philosophy.

What is the nature of your responsibility? The whole concept of mentor has had a checkered path in the world of work. The most typical mental image has been that of a seasoned corporate sage conversing with a naïve, wet-behind-the-ears young recruit. The conversation would probably have been laced with informal rules, closely guarded secrets, and “I remember back in ’77 … ” stories of daredevil heroics and too-close-to-call tactics. And work-based mentoring has had an almost heady, academic sound, reserved solely for workers in white collars whose fathers advised, “Get to know ol’ Charlie.”

In recent years the term “mentor” became connected less with privilege and more with affirmative action. An organization viewed as a part of its responsibility enabling minority employees through a mentor to expedite their route through glass ceilings, beyond old-boy networks and the private winks formerly reserved for WASP males. Such mentoring sponsors sometimes salved the consciences of those who bravely talked goodness but became squeamish if expected to spearhead courageous acts. These mentoring programs sounded contemporary and forward-thinking. Some were of great service, but many were just lip service.

But what are the role and responsibility of mentoring, really? When the package is unwrapped and the politically correct is scraped away, what’s left? A mentor is defined in the dictionary as “a wise, trusted advisor … a teacher or coach.” Such a simple definition communicates a plain-vanilla context. In case you missed the preface, mentoring is defined as that part of the leader’s role that has learning as its primary outcome. Bottom line, a mentor is simply someone who helps someone else learn something that would have otherwise been learned less well, more slowly, or not at all. Notice the power-free nature of this definition; mentors are not power figures.

The traditional use of the word “mentor” denotes a person outside one’s usual chain of command—from the junior’s point of view, someone who “can help me understand the informal system and offer guidance on how to be successful in this crazy organization.” Not all mentors are supervisors or managers, but most effective supervisors and managers act as mentors. Mentoring is typically focused on one person; group mentoring is training or teaching. We will focus on the one-to-one relationship; the others are beyond the scope of this book.

Good leaders do a lot of things in the organizations they inhabit. Good leaders communicate a clear vision and articulate a precise direction. Good leaders provide performance feedback, inspire and encourage, and, when necessary, discipline. Good leaders also mentor. Once more, mentoring is that part of a leader’s role that has growth as its primary outcome.

Lessons from the First Mentor

The word “mentor” comes from The Odyssey, written by the Greek poet Homer. As Odysseus (Ulysses, in the Latin translation) is preparing to go fight the Trojan War, he realizes he is leaving behind his one and only heir, Telemachus. Since “Telie” (as he was probably known to his buddies) is in junior high, and since wars tended to drag on for years (the Trojan War lasted ten), Odysseus recognizes that Telie needs to be coached on how to “king” while Daddy is off fighting. He hires a trusted family friend named Mentor to be Telie’s tutor. Mentor is both wise and sensitive—two important ingredients of world-class mentoring.

The history of the word “mentor” is instructive for several reasons. First, it underscores the legacy nature of mentoring. Like Odysseus, great leaders strive to leave behind a benefaction of added value. Second, Mentor (the old man) combined the wisdom of experience with the sensitivity of a fawn in his attempts to convey kinging skills to young Telemachus. We all know the challenge of conveying our hard-won wisdom to another without resistance. The successful mentor is able to circumvent resistance.

Homer characterizes Mentor as a family friend. The symbolism contained in this relationship is apropos to contemporary mentors. Effective mentors are like friends in that their goal is to create a safe context for growth. They are also like family in that their focus is to offer an unconditional, faithful acceptance of the protégé. Friends work to add and multiply, not subtract. Family members care, even in the face of mistakes and errors.

Superior mentors know how adults learn. Operating out of their intuition or on what they have learned from books, classes, or other mentors, the best mentors recognize that they are, first and foremost, facilitators and catalysts in a process of discovery and insight. They know that mentoring is not about smart comments, eloquent lectures, or clever quips. Mentors practice their skills with a combination of never-ending compassion, crystal-clear communication, and a sincere joy in the role of being a helper along a journey toward mastering.

Just like the first practitioner of their craft, mentors love learning, not teaching. They treasure sharing rather than showing off, giving rather than boasting. Great mentors are not only devoted fans of their protégés, they are loyal fans of the dream of what their protégés can become with their guidance.

Traps to Avoid

There are countless traps along the path of mentordom. Mentoring can be a power trip for those seeking an admirer, a manifestation of greed for those who must have slaves. Mentoring can be a platform for proselytizing for a cause or crusade, a strong tale told to an innocent or unknowing listener. However, the traps of power, greed, and crusading all pale when compared with the subtler “watch out fors” listed below. There are other traps, of course, but these are the ones that most frequently raise their ugly heads to sabotage healthy relationships.

Keep the traps in mind as you read the rest of the book; search for them within yourself. By the time you’ve read the last page, you will perhaps have learned to avoid those to which you are most susceptible.

I Can Help

When is help helpful and when is it harmful? People inclined to be charitable with their time, energy, and expertise often attempt to help when what the learner actually needs is to struggle and find her own way. Here’s a test: if you ask the protégé, “May I help?” and she says no, how do you feel? Be honest with yourself. If you react with even a trace of rejection and self-pity, this may be your trap to avoid.

I Know Best

Some people become mentors because they enjoy being recognized as someone in the know. They relish the affirmations from protégés who brag to others about their helpful mentor. They especially like protégés who regularly compliment them on their contribution. This is a trap! You may get off track and end up using the protégé for your own recognition needs. The test? If your protégé comes to you and says that he has found someone else who might be more helpful as a mentor, how do you react? If you feel more than mild and momentary disappointment, beware! This may be your special trap.

I Can Help You Get Ahead

Mentors can be useful in getting around organizational barriers, getting into offices otherwise closed, and getting special tips useful in climbing the ladder of success. As sometime kingmakers, they make promises that can carry an “I can get it for you wholesale” seduction. All these “gettings” can be valuable and important. They can also add a bartering, sinister component to an otherwise promising relationship. The “You scratch my back, and …” approach to mentoring relationships can infuse a scorekeeping dimension that is detrimental to both parties. Although reciprocity can be important, a tit-for-tat aspect can lead one person in the relationship to a scorekeeping, “You owe me one” view of the relationship.

You Need Me

When mentors feel that their protégés need them, they are laying the groundwork for a relationship based on dependence. Although many mentor-protégé partnerships begin with some degree of dependence, the goal is to transform the relationship into one of strength and interdependence. A relationship based on dependence can ultimately become a source of resentment for the protégé, false power for the mentor.

If the protégé views the mentoring process as a chore or a necessary ritual, it is generally a dependent relationship that will not be allowed to grow up. Remember, the focus should be on helping the protégé become strong, not on helping the protégé feel better about being weak.

The Qualities of Great Mentoring

Great mentors are not immune to traps; great mentors recognize the traps they are likely to fall into and work hard to compensate for them. How do they do that? They do it by understanding the qualities of a mentor-protégé relationship focused on discovery and learner independence—and then learning to be living, breathing models of those qualities.

First and foremost, great mentoring is a partnership. And partnership starts with balance.

Balance

Unlike a relationship based on power and control, a learning partnership is a balanced alliance, grounded in mutual interests, interdependence, and respect. Power-seeking mentors tend to mentor with credentials and sovereignty; partnership-driven mentors seek to mentor with authenticity and openness. In a balanced learning partnership, energy is given early in the relationship to role clarity and communication of expectations; there is a spirit of generosity and acceptance rather than a focus on rules and rights. Partners recognize their differences while respecting their common needs and objectives.

Truth

Countless books extol the benefits of clear and accurate communication. Partnership communication has one additional quality: it is clean, pure, characterized by the highest level of integrity and honesty. Truth-seekers work not only to ensure that their words are pure (the truth and nothing but the truth) but also to help others communicate with equal purity. When a mentor works hard to give feedback to a protégé in a way that is caringly frank and compassionately straightforward, it is in pursuit of clean communication. When a mentor implores the protégé for candid feedback, it is a plea for clean communication. The path of learning begins with the mentor’s genuineness and candor.

Trust

Trust begins with experience; experience begins with a leap of faith. Perfect monologues, even with airtight proof and solid support documentation, do not foster a climate of experimentation and risk taking. They foster passive acceptance, not personal investment. If protégés see their mentors taking risks, they will follow suit. A “trust-full” partnership is one in which error is accepted as a necessary step on the path from novice to master.

Abundance

Partnership-driven mentors exude generosity. There is a giver orientation that finds enchantment in sharing wisdom. As the “Father of Adult Learning,” Malcolm Knowles, says, “Great trainers [and mentors] love learning and are happiest when they are around its occurrence.”1 Such relationships are celebratory and affirming. As the mentor gives, the protégé reciprocates, and abundance begins to characterize the relationship. And there is never a possessive, credit-seeking dimension (“That’s MY protégé”).

Passion

Great mentoring partnerships are filled with passion; they are guided by mentors with deep feelings and a willingness to communicate those feelings. Passionate mentors recognize that effective learning has a vitality about it that is not logical, not rational, and not orderly. Such mentors get carried away with the spirit of the partnership and their feelings about the process of learning. Some may exude emotion quietly, but their cause-driven energy is clearly present. In a nutshell, mentors not only love the learning process, they love what the protégé can become—and they passionately demonstrate that devotion.

Courage

Mentoring takes courage; learning takes courage. Great mentors are allies of courage; they cultivate a partnership of courageousness. They take risks with learning, showing boldness in their efforts, and elicit courage in protégés by the examples they set. The preamble to learning is risk, the willingness to take a shaky step without the security of perfection. The preamble to risk is courage.

Ethics

Effective mentors must be clean in their learner-dealings, not false, manipulative, or greedy. Competent mentors must be honest and congruent in their communications and actions. They must not steal their learners’ opportunities for struggle or moments of glory. Great mentors refrain from coveting their learners’ talents or falsifying their own. They must honor the learner just as they honor the process of mutual learning.

Partnerships are the expectancy of the best in our abilities, attitudes, and aspirations. In a learning partnership, the mentor is not only helping the protégé but also continually communicating a belief that he or she is a fan of the learner. Partnerships are far more than good synergy. Great partnerships go beyond “greater than” to a realm of unforeseen worth. And worth in a mentoring partnership is laced with the equity of balance, the clarity of truth, the security of trust, the affirmation of abundance, the energy of passion, the boldness of courage, and the grounding of ethics.

The Real Aim of Mentoring:

Mastering, Not Mastery

George is someone who has never been a person of moderation. When George was in college, he joined a group of fellow wayward students to take a forbidden midnight swim in the pool at the girls’ gym on the other side of a tall, locked chain-link fence. George was the one who decided everyone should make it a skinny-dipping adventure. The fact that George was the only one who stripped never seemed to bother him. It was not surprising that years later, after reading the best-selling book Swim with the Sharks without Being Eaten Alive, George went to a pet store and boldly bought a live shark for his Miami apartment. Though less than a foot long, it was a real shark—with a distinctive white dorsal fin rising out of its gun-metal-gray body. George named the little fish Harvey after the book’s author, Harvey Mackay.

Sometime later, George’s life took an unexpected turn. He was promoted to regional sales manager of his company and transferred to Houston. Knowing he was going to be on the road a lot, George worried about who would take care of little Harvey. So he gave the shark to Sea World in Orlando. Harvey moved from a two-gallon fish bowl to an aquarium the size of a three-story house.

Several years went by. When George got married, the inextinguishable kid in George picked Walt Disney World as the perfect honeymoon site. While he and his wife were in Orlando, they decided to go by Sea World and check on little Harvey. They were stunned. Harvey now was almost ten feet long and weighed nearly five hundred pounds.

When George told one of us about Harvey, we thought it was another of his tall tales. But George was convincing. Apparently certain animals—like sharks, and like humans—grow commensurately with their surroundings. Google it if you don’t believe us! If we are to grow to our greatest potential, we need a safe and unrestricted environment.

To grow is fundamentally the act of expanding, an unfolding into greatness. And so expansiveness is the most important attribute of a great mentoring relationship. Mentoring effectiveness is all about clearing an emotional path to make the learning journey as free of boundaries as possible. Change is a door opened from the inside. But it is the mentoring relationship that delivers the key to that door.

The real aim of mentoring is not mastery. Mastery implies closure, an ending, arrival at a destination. In today’s ever-changing world, the goal is “mastering,” a never-ending, ever-expansive journey of perpetual growth. It suggests the relationship is more important than the goal, that the process is more valued than the outcome.

Busting the Boundaries

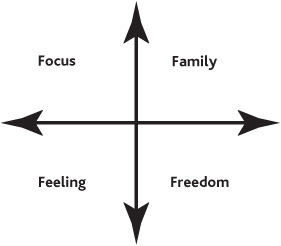

So what can a mentor do to set up an expansive, boundary-free learning environment? Extensive research shows that great mentors give unswerving attention to four essential components: focus, feeling, family, and freedom.

Focus

There are several ways adult learning (andragogy) is different from child learning (pedagogy). Adults are motivated to learn when they perceive an immediate or short-term rationale for that learning. You can tell a child, “This history you are learning in the classroom may not be useful on the playground at recess, but someday it will be helpful to you” and retain their interest. Adults are not so gullible. Granted, some adults get a kick out of learning purely for learning’s sake, but they are in the minority. Most adults are motivated to learn if the effort will have a clear payoff in the present or—at most—in the very near future.

The mentoring partnership must be conducted so that the protégé knows the purpose of the learning. There needs to be an “as a result of this learning, you will be able to …” component woven through your partnership. In the organizational context, it helps to anchor the learning to the unit or organizational vision or mission, to unit objectives, and to the protégé’s personal or professional goals and aspirations. The tie must be subtle … and at the same time obvious. It should be an initial focus … and a perpetual one. Anchoring learning to objectives is one way to create useful guide-posts for measuring success. Think of focus as not only the basis for your interaction but as the very language you speak.

Feeling

Do you remember what you learned about relationships when you were in high school? Remember that friendship that went sour and how you worked so hard to get it back together? Remember going steady, breaking up, having fights, making up … and on and on? The lessons learned in those heart-pain days seem indelibly etched in our memories. They are the lessons we teach our children, nieces or nephews, or friends’ children.

Now think about other things you learned in high school. Maybe you learned sine, cosine, and tangent. You learned to conjugate verbs and diagram sentences. You knew the length of the Amazon River, the height of the Empire State Building and could name the capital of every state in the union—including South Dakota and Kentucky! And you probably got A’s on those tests. Remember? If there were a pop quiz today, how would you fare? Somehow, most learning that is not anchored to the heart is not retained.

The mentoring relationship is at its best when it is conducted with spirit and emotion. Talk with someone who has served in a combat role in war. They can tell you intricate details of the conflicts but only vaguely about the time spent in training. The lessons learned in combat were lessons of the heart, imprinted with the passion of the most exhilarating highs and the most depressing lows. Part of the mentor’s job is to foster an environment where feelings, emotions, and learning are tightly linked.

Family

Mentoring works best when implemented in the spirit of partnership. In The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge talks about another’s “fellowship” as a key support for learning, but we think “family” is a better “f” word to capture the spirit of partnership. Fellowship could be simply an association, but “family” implies a much deeper relationship. Learning requires risk taking and experimentation. It necessitates error and mistake. It is uniquely difficult for a mentor to carry out an insight goal (fostering discovery) from an in-charge (I’m the boss) role. Even if the mentor is not in a functional managerial role, simply being an “expert” creates the potential of unequal power. Applied to mentor and protégé, “family” implies a close relationship, not a parent-child relationship. The goal is partnership.

Freedom

The ultimate test of the expansiveness of the mentoring relationship is when the learner is set free. Mentoring relationships are exercises in ceaseless letting go. Few conditions do a greater disservice to the protégé than mentor dependence. Dependence leads to protégé uncertainty and insecurity. Dependence results in a relationship that is inefficient and barren of worth to either mentor or protégé. Dependence implies the mentor is the sole repository of the wisdom required by the protégé.

Engendering freedom is all about creating strength and courage. Fostering freedom is also about building bridges to other resources, including linking the protégé up with other mentors. It means helping the protégé connect with a storehouse of resources to be accessed as needed.

SAGE: The Model for Great Mentoring

If the aim is to nurture “mastering”—through a mentoring partnership focused on learner discovery and independence, in a climate that reduces boundaries and encourages risk—what are the steps or stages needed to reach that aim?

The mentoring model found in this book is built around the belief that great mentoring requires four core competencies, each of which can be applied in many ways. These competencies form the sequential steps in the process of mentoring. All four have been selected for their ability to blend effectively. Not accidentally, the first letters of these four competencies (and steps) spell the word “SAGE”—a helpful mnemonic as well as a symbolic representation of the goal, the power-free facilitation of learning. They are:

Surrendering—leveling the learning field;

Accepting—creating a safe haven for risk taking;

Gifting—the core contributions of the mentor, the Main Event; and

Extending—nurturing protégé independence.

Surrendering

Most leaders are socially conditioned to drive the process of learning; great mentors surrender to it. Driving the process has many unfortunate effects. It tends to cause resistance; it minimizes the potential for serendipitous growth, and it tilts the focus from competence to control.

If there is one word many leaders hate, it is the word “surrender.” However, by “surrender” we don’t mean losing but yielding to a flow greater than either player in the process. The dictionary defines “surrender” as “to yield possession of.” Mentors who attempt to hold, own, or control the process deprive their protégés of the freedom needed to foster discovery.

Surrendering is the process of leveling the learning field. Most mentoring relationships begin with mentor and protégé in unequal power positions … boss to subordinate, master to novice, or teacher to student. The risk is that power creates anxiety and anxiety minimizes risk taking—that ever-important ingredient required for growth. Surrendering encompasses all the actions the mentor takes to pull power and authority out of the mentoring relationship so protégé anxiety is lowered and courage is heightened.

Accepting

Accepting is the act of inclusion. Acceptance is what renowned psychologist Carl Rogers labeled “unconditional positive regard.” Most managers are taught to focus on exclusion. Exclusion is associated with preferential treatment, presumption, arrogance, and insolence—growth killers all. The verb “accept,” however, implies ridding oneself of bias, preconceived judgments, and human labeling. Accepting is embracing, rather than evaluating or judging.

Accepting is code for creating an egalitarian, safe haven for learning. When mentors demonstrate noticeable curiosity, they telegraph acceptance. When mentors encourage and support, they send a message that safety abounds. Protégés need safety in the mentoring relationship in order to undertake experimental behavior in the face of public vulnerability.

Gifting

Gifting is the act of generosity. Gifting, as opposed to giving, means bestowing something of value upon another without expecting anything in return. Mentors have many gifts to share. When they bestow those gifts abundantly and unconditionally, they strengthen the relationship and keep it healthy. Gifting is the antithesis of taking or using manipulatively. It is at the opposite end of the spectrum from greed.

Gifting is often seen as the main event of mentoring. Mentors gift advice, they gift feedback, they gift focus and direction, they gift the proper balance between intervening and letting protégés test their wings, and they gift their passion for learning. However, just as we all recoil at the sound of “Let me give you some advice,” protégés must be ready for the mentor’s gifts. Surrendering and accepting are important initial steps in creating a readiness in the protégé. Gifts are wasted when they are not valued—when they are discounted and discarded.

Extending

Extending means pushing the relationship beyond its expected boundaries. Mentors who extend are those willing to give up the relationship in the interest of growth, to seek alternative ways to foster growth. They recognize that the protégé’s learning can occur and be enhanced in many and mysterious ways. Extending is needed to create an independent self-directed learner.

Surrendering, accepting, gifting, and extending are the capabilities or proficiencies required for the mentor to be an effective partner in the protégé’s growth. These four core competencies also serve as the organizing structure for the rest of this book. Their sequence is important. The process of mentoring begins with surrendering and ends with extending. Under each of the four competencies you will find several chapters full of techniques for demonstrating that competence effectively.

Mentoring is an honor. Except for love, there is no greater gift one can give another than the gift of growth. It is a rare privilege to help another learn, have the relevant wisdom to be useful to another, and partner with someone who can benefit from that wisdom. This book is crafted with a single goal: to help you exercise that honor and privilege in a manner that benefits you and all those you influence.