This is a pragmatic, hands-on, up-to-date guide to determining right and wrong in the business world. Joseph Weiss integrates a stakeholder perspective with an issues-oriented approach so students look at how a business's actions affect not just share price and profit but the well-being of employees, customers, suppliers, the local community, the larger society, other nations, and the environment.

Weiss uses a wealth of contemporary examples, including twenty-three customized cases that immerse students directly in recent business ethics dilemmas and ask them to consider how they would resolve them. The recent economic collapse raised ethical issues that have yet to be resolved—there could not be a better time for a fully updated edition of Weiss's classic, accessible blend of theory and practice.

New to the Sixth Edition!

New Cases! Fourteen of the twenty-three cases in this book are brand new to this edition. They touch on issues such as cyberbullying, fracking, neuromarketing, and for-profit education and involve institutions like Goldman Sachs, Google, Kaiser Permanente, Walmart, Ford, and Facebook.

Updated Throughout! The text has been updated with the latest research, including new national ethics survey data, perspectives on generational differences, and global and international issues. Each chapter includes recent business press stories touching on ethical issues.

New Feature! Several chapters now feature a unique Point/Counterpoint exercise that challenges students to argue both sides of a contemporary issue, such as too-big-to-fail institutions, the Boston bomber Rolling Stone cover, student loan debt, online file sharing, and questions raised by social media.

This is a pragmatic, hands-on, up-to-date guide to determining right and wrong in the business world. Joseph Weiss integrates a stakeholder perspective with an issues-oriented approach so students look at how a business's actions affect not just share price and profit but the well-being of employees, customers, suppliers, the local community, the larger society, other nations, and the environment.

Weiss uses a wealth of contemporary examples, including twenty-three customized cases that immerse students directly in recent business ethics dilemmas and ask them to consider how they would resolve them. The recent economic collapse raised ethical issues that have yet to be resolved—there could not be a better time for a fully updated edition of Weiss's classic, accessible blend of theory and practice.

New to the Sixth Edition!

New Cases! Fourteen of the twenty-three cases in this book are brand new to this edition. They touch on issues such as cyberbullying, fracking, neuromarketing, and for-profit education and involve institutions like Goldman Sachs, Google, Kaiser Permanente, Walmart, Ford, and Facebook.

Updated Throughout! The text has been updated with the latest research, including new national ethics survey data, perspectives on generational differences, and global and international issues. Each chapter includes recent business press stories touching on ethical issues.

New Feature! Several chapters now feature a unique Point/Counterpoint exercise that challenges students to argue both sides of a contemporary issue, such as too-big-to-fail institutions, the Boston bomber Rolling Stone cover, student loan debt, online file sharing, and questions raised by social media.

Joseph W. Weiss, PhD, is Professor of Management and Senior Fellow with the Center of Business Ethics at Bentley University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He specializes in Executive Leadership Development, Business Ethics, and Management & Technology. He served as a Senior Fulbright Program Specialist in Moscow and Madrid and was a business program evaluator with the Fulbright program for two years. He has taught and lectured in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. He is author of several books and articles in the fields of business ethics, project management, leadership, organizational change, and technology management. He has won awards in his university teaching, and was Chair of the Consulting Division in the national Academy of Management. He consults to companies in organizational change, leadership development, and business ethics.

Chapter 2 Ethical Principles, Quick Tests, and Decision-Making

Chapter 3 Stakeholder and Issues Management Approaches

Chapter 4 The Corporation and External Stakeholders: Corporate Governance: From the Boardroom to the Marketplace

Chapter 5 Corporate Responsibilities, Consumer Stakeholders, and the Environment

Chapter 6 The Corporation and Internal Stakeholders: Values-Based Moral Leadership, Culture, Strategy, and Self-Regulation

Chapter 7 Employee Stakeholders and the Corporation

Chapter 8 Business Ethics Stakeholder Management in the Global Environment

NOTES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Index

1

BUSINESS ETHICS, THE CHANGING ENVIRONMENT, AND STAKEHOLDER MANAGEMENT

1.1 Business Ethics and the Changing Environment

1.2 What Is Business Ethics? Why Does It Matter?

1.4 Five Myths about Business Ethics

1.5 Why Use Ethical Reasoning in Business?

1.6 Can Business Ethics Be Taught and Trained?

1. Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC: Wall Street Trading Firm

2. Cyberbullying: Who’s to Blame and What Can Be Done?

OPENING CASE

Blogger: “Hi. i download music and movies, limewire and torrent. is it illegal for me to download or is it just illegal for the person uploading it. does anyone know someone who was caught and got into trouble for it, what happened them. Personally I dont see a difference between downloading a song or taping it on a cassette from a radio!!”1

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), on behalf of its member companies and copyright owners, has sued more than 30,000 people for unlawful downloading. RIAA detectives log on to peer-to-peer networks where they easily identify illegal activity since users’ shared folders are visible to all. The majority of these cases have been settled out of court for $1,000—$3,000, but fines per music track can go up to $150,000 under the Copyright Act.

The nation’s first file-sharing defendant to challenge an RIAA lawsuit, Jammie Thomas-Rasset, reached the end of the appeals process to overturn a jury-determined $222,000 fine in 2013. She was ordered to pay this amount, which she argued was unconstitutionally excessive, for downloading and sharing 24 copyrighted songs using the now-defunct file-sharing service Kazaa. The Supreme Court has not yet heard a file-sharing case, having also declined without comment to review the only other appeal following Thomas-Rasset’s. (In that case, the Court let stand a federal jury-imposed fine of $675,000 against Joel Tenenbaum for downloading and sharing 30 songs.) “As I’ve said from the beginning, I do not have now, nor do I anticipate in the future, having $220,000 to pay this,” Thomas-Rasset said. “If they do decide to try and collect, I will file for bankruptcy as I have no other option.”2

Students often use university networks to illegally distribute copyrighted sound recordings on unauthorized peer-to-peer services. The RIAA has issued subpoenas to universities nationwide, including networks in Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. Most universities give up students’ identities only after offering an opportunity to stop the subpoena with their own funds. As in earlier rounds of lawsuits, the RIAA is utilizing the “John Doe” litigation process, which is used to sue defendants whose names are not known.

RIAA president Cary Sherman has discussed the ongoing effort to reach out to the university community with proactive solutions to the problem of illegal file-sharing on college campuses: “It remains as important as ever that we continue to work with the university community in a way that is respectful of the law as well as university values. That is one of our top priorities, and we believe our constructive outreach has been enormously productive so far. Along with offering students legitimate music services, campus-wide educational and technological initiatives are playing a critical role. But there is also a complementary need for enforcement by copyright owners against the serious offenders—to remind people that this activity is illegal.”

He added: “Illegally downloading music from the Internet costs everyone—the musicians not getting compensated for their craft, the owners and employees of the thousands of record stores that have been forced to close, legitimate online music services building their businesses, and consumers who play by the rules and purchase their music legally.”

On the other hand, once the well-funded RIAA initiates a lawsuit, many defendants are pressured to settle out of court in order to avoid oppressive legal expenses. Others simply can’t take the risk of large fines that juries have shown themselves willing to impose.

New technologies and the trend toward digital consumption have made intellectual property both more critical to businesses’ bottom lines and more difficult to protect. No company, big or small, is immune to the intellectual property protection challenge. Illegal downloads of music are not the only concern. A new wave of lawsuits is being filed against individuals who illegally download movies through sites like Napster and BitTorrent. In 2011, the U.S. Copyright Group initiated “the largest illegal downloading case in US history” at the time, suing over 23,000 file sharers who illegally downloaded Sylvester Stallone’s movie The Expendables. This case was expanded to include the 25,000 users who also downloaded Voltage Pictures’ The Hurt Locker, which increased the total number of defendants to approximately 50,000, all of whom used peer-to-peer downloading through BitTorrent. The lawsuits were filed based on the illegal downloads made from an Internet Protocol (IP) address. The use of an IP address as identifier presents ethical issues—for example, should a parent be responsible for a child downloading a movie through the family’s IP address? What about a landlord who supplied Internet to a tenant?

Digital books are also now in play. In 2012, a lawsuit was filed in China against technology giant Apple for sales of illegal book downloads through its App Store. Nine Chinese authors are demanding payment of $1.88 million for unauthorized versions of their books that were submitted to the App Store and sold to consumers for a profit. Again, the individual IP addresses are the primary way of determining who performed the illegal download. Telecom providers and their customers face privacy concerns, as companies are being asked for the names of customers associated with IP addresses identified with certain downloads.

Privacy activists argue that an IP address (which identifies the subscriber but not the person operating the computer) is private, protected information that can be shown during criminal but not civil investigations. Fred von Lohmann, senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, has suggested on his organization’s blog that “courts are not prepared to simply award default judgments worth tens of thousands of dollars against individuals based on a piece of paper backed by no evidence.”3

1.1 Business Ethics and the Changing Environment

The Internet is changing everything: the way we communicate, relate, read, shop, bank, study, listen to music, get news and “TV,” and participate in politics. Of course the last “third billion” of people in undeveloped countries are not participating on broadband as is the rest of the world,4 but they predictably will, first through mobile phones. Businesses and governments operate in and are disrupted by changing technological, legal, economic, social, and political environments with competing stakeholders and power claims, as many Middle Eastern countries in particular are experiencing. Also, as this chapter’s opening case shows, there is more than one side to every complex issue and debate involving businesses, consumers, families, other institutions, and professionals. When stakeholders and companies cannot agree or negotiate competing claims among themselves, the issues generally go to the courts.

The RIAA, in the opening case, does not wish to alienate too many college students because they are also the music industry’s best customers. At the same time, the association believes it must protect those groups it represents. Not all stakeholders in this controversy agree on goals and strategies. For example, not all music artists oppose students downloading or even sharing some of their copyrighted songs. Offering free access to some songs is a good advertising tactic. On the other hand, shouldn’t those songwriters and recording companies who spend their time and money creating, marketing, distributing, and selling their intellectual property protect that property? Is file sharing, without limits or boundaries, stealing other people’s property? If not, what is this practice to be called? If file sharing continues in some form, and ends up helping sales for many artists, will it become legitimate? Should it? Is this just the new way business models are being changed by 15–26 year olds? While the debate continues, individuals (15 year olds and younger in many cases) who still illegally share files have rights as private citizens under the law, and recording companies have rights of property protection. Who is right and who is wrong, especially when two rights collide? Who stands to lose and who to gain? Who gets hurt by these transactions? Which group’s ethical positions are most defensible?

Stakeholders are individuals, companies, groups, and even governments and their subsystems that cause and respond to external issues, opportunities, and threats. Corporate scandals, globalization, deregulation, mergers, technology, and global terrorism have accelerated the rate of change and brought about a climate of uncertainty in which stakeholders must make business and moral decisions. Issues concerning questionable ethical and illegal business practices confront everyone, as the following examples illustrate:

• The subprime lending crisis in 2008 involved stakeholders as varied as consumers, banks, mortgage companies, real estate firms, and homeowners. Many companies that sold mortgages to unqualified buyers lied about low-risk, high-return products. Wall Street companies, while thriving, are also settling lawsuits stemming from the 2008 crisis. In 2013, “Hundreds of thousands of subprime borrowers are still struggling. Subprime securities still pose a significant legal risk to the firms that packaged them, and they use up capital that could be deployed elsewhere in the economy.”5 In 2011, Bank of America announced that it would “take a whopping $20 billion hit to put the fallout from the subprime bust behind it and satisfy claims from angry investors.”6 The ethics and decisions precipitating the crisis contributed to tilting the U.S. economy toward recession, with long-lasting effects.

• The corporate scandals in the 1990s through 2001 at Enron, Adelphia, Halliburton, MCI WorldCom, Tyco, Arthur Andersen, Global Crossing, Dynegy, Qwest, Merrill Lynch, and other firms that once jarred shareholder and public confidence in Wall Street and corporate governance may now seem like ancient history to those with short-term memories. Enron’s bankruptcy with assets of $63.4 billion defies imagination, but WorldCom’s bankruptcy set the record for the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history (Benston, 2003). Only 22% of Americans express a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in big business, compared to 65% who express confidence in small business.7 Confidence in big business reached its highest point in 1974 at 34%, and even during the dot-com boom in the late 1990s it hovered at 30%. The lowest rating of 16% was polled in 2009 after the subprime lending crisis, and although public confidence has slightly increased, the significant differential in American confidence between big and small business belies a public mistrust of big business that may not be easily repaired.8

• The debate continues over excessive pay to those chief executive officers (CEOs) who posted poor corporate performance. Large bonuses paid out during the financial crisis made executive pay a controversial topic, yet investors did little to solve the issue. “Investors had the opportunity to provide advisory votes on executive pay at financial firms that received TARP funds in 2009, and they gave thumbs up to pay packages at every single one of those institutions. This proxy season, with advisory votes now widely available (thanks to the Dodd-Frank Act), only five companies’ executive compensation packages have received a thumbs down from shareholders.”9 The Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that while median CEO salaries grew at 27% in 2010, overall worker pay only increased by 2.1%. “It’s been almost three years since Congress directed the Securities and Exchange Commission to require public companies to disclose the ratio of their chief executive officers’ compensation to the median of the rest of their employees’. The agency has yet to produce a rule.”10 An independent 2013 analysis by Bloomberg showed that “Across the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index of companies, the average multiple of CEO compensation to that of rank-and-file workers is 204, up 20 percent since 2009.”11

• Some critics on the right of the political spectrum argue that companies are becoming overregulated since the scandals. Others argue there is not sufficient regulation of the largest financial companies. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 is one response to those scandals. This act states that corporate officers will serve prison time and pay large fines if they are found guilty of fraudulent financial reporting and of deceiving shareholders. Implementing this legislation requires companies to create accounting oversight boards, establish ethics codes, show financial reports in greater detail to investors, and have the CEO and chief financial officer (CFO) personally sign off on and take responsibility for all financial statements and internal controls. Implementing these provisions is costly for corporations. Some claim their profits and global competitiveness are negatively affected and the regulations are “unenforceable.”12

• U.S. firms are outsourcing work to other countries to cut costs and improve profits, work that some argue could be accomplished in the United States. Estimates of U.S. jobs outsourced range from 104,000 in 2000 to 400,000 in 2004, and to a projected 3.3 million by 2015. “Forrester Research estimated that 3.3 million U.S. jobs and about $136 billion in wages would be moved to overseas countries such as India, China, and Russia by 2015. Deloitte Consulting reported that 2 million jobs would move from the United States and Europe to overseas destinations within the financial services business. Across all industries the emigration of service jobs can be as high as 4 million.”13 Do U.S. employees who are laid off and displaced need protection, or is this practice part of another societal business transformation? Is the United States becoming part of a global supply chain in which outsourcing is “business as usual” in a “flat world,” or is the working middle class in the United States and elsewhere at risk of predatory industrial practices and ineffective government polices?14

• Will robots, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI) applications replace humans in the workplace? This interesting but disruptive development poses concerns. “The outsourcing of human jobs as a side effect of globalization has arguably contributed to the current unemployment crisis. However, a growing trend sees humans done away with altogether, even in the low-wage countries where many American jobs have landed”.15 What will be the ethical implications of the next wave of AI development, “where full-blown autonomous self-learning systems take us into the realm of science fiction—delivery systems and self-driving vehicles alone could change day-to-day life as we know it, not to mention the social implications.”16 AI also extends into electronic warfare (drones), education (robot assisted or led), and manufacturing (a Taiwanese company replaced a “human force of 1.2 million people with 1 million robots to make laptops, mobile devices and other electronics hardware for Apple, Hewlett-Packard, Dell and Sony”).17 One futurist predicted that as many as 50 million jobs could be lost to machines by 2030, and even 50% of all human jobs by 2040.

These large macro-level issues underlie many ethical dilemmas that affect business and individual decisions among stakeholders in organizations, professions, as well as individual lives. Before discussing stakeholder theory, and the management approach that it is based on, and how these perspectives and methods can help individuals and companies better understand how to make more socially responsible decisions, we take a brief look at the broader environmental forces that affect industries, organizations, and individuals.

Seeing the “Big Picture”

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Thomas Friedman, continues to track megachanges on a global scale. His 2011 book, That Used to Be Us: How America Fell Behind in the World It Invented and How We Can Come Back, suggests an agenda for change to meet larger challenges. His books, The World Is Flat 3.0, and The Lexus and the Olive Tree, vividly illustrate a macroenvironmental perspective that provides helpful insights into stakeholder and issues management mind-sets and approaches.18 Friedman notes, “Like everyone else trying to adjust to this new globalization system and bring it into focus, I had to retrain myself and develop new lenses to see it. Today, more than ever, the traditional boundaries between politics, culture, technology, finance, national security, and ecology are disappearing. You often cannot explain one without referring to the others, and you cannot explain the whole without reference to them all. I wish I could say I understood all this when I began my career, but I didn’t. I came to this approach entirely by accident, as successive changes in my career kept forcing me to add one more lens on top of another, just to survive.”19

After quoting Murray Gell-Mann, the Nobel laureate and former professor of theoretical physics at Caltech, Friedman continues, “We need a corpus of people who consider that it is important to take a serious and professional look at the whole system. It has to be a crude look, because you will never master every part or every interconnection. Unfortunately, in a great many places in our society, including academia and most bureaucracies, prestige accrues principally to those who study carefully some [narrow] aspect of a problem, a trade, a technology, or a culture, while discussion of the big picture is relegated to cocktail party conversation. That is crazy. We have to learn not only to have specialists but also people whose specialty is to spot the strong interactions and entanglements of the different dimensions, and then take a crude look at the whole.”20

POINT/COUNTERPOINT

File Sharing: Harmful Theft or Sign of the Times?

This exercise provides a more complete case with student interaction.

“I watch some of my favorite shows on hulu.com for free and I buy others on Amazon or iTunes. I pay a fee to use Pandora for ad-free internet radio, or Spotify for specific music playlists. But like many of my friends, I don’t own a TV, so when there is no other way to access a show, I will download it from a torrent [file-sharing] site.”

—Interview with a Generation Y “Millennial”

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), on behalf of its member companies and copyright owners, has sued more than 30,000 people for unlawful downloading. RIAA detectives log on to peer-to-peer networks where they easily identify illegal activity since users’ shared folders are visible to all. The majority of these cases have been settled out of court for $1,000—$3,000, but fines per music track can go up to $150,000 under the Copyright Act.

The nation’s first file-sharing defendant to challenge an RIAA lawsuit, Jammie Thomas-Rasset, in 2013 reached the end of the appeals process to overturn a jury-determined $222,000 fine. She was ordered to pay this amount, which she argued was unconstitutionally excessive, for downloading and sharing 24 copyrighted songs using the now-defunct file-sharing service Kazaa. The Supreme Court has not yet heard a file-sharing case, having also declined without comment to review the only other appeal following Thomas-Rasset’s.

Students often use university networks to illegally distribute copyrighted sound recordings on unauthorized peer-to-peer services. The RIAA issues subpoenas to universities nationwide, including networks in Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. Most universities give up students’ identities only after offering an opportunity to stop the subpoena with their own funds. As in earlier rounds of lawsuits, the RIAA is utilizing the “John Doe” litigation process, which is used to sue defendants whose names are not known.

RIAA President Cary Sherman cites the ongoing effort to reach out to the university community with proactive solutions to the problem of illegal file sharing on college campuses, saying, “It remains as important as ever that we continue to work with the university community in a way that is respectful of the law as well as university values. . . . Along with offering students legitimate music services, campus-wide educational and technological initiatives are playing a critical role. But there is also a complementary need for enforcement by copyright owners against the serious offenders—to remind people that this activity is illegal and . . . costs everyone.”

On the other hand, once the well-funded RIAA initiates a lawsuit, many defendants are pressured to settle out of court in order to avoid oppressive legal expenses. Others simply can’t take the risk of large fines that juries have shown themselves willing to impose.

New technologies and the trend toward digital consumption have made intellectual property both more critical to businesses’ bottom line and more difficult to protect. No company, big or small, is immune to the IP protection challenge. Illegal downloads of music are not the only concern. A new wave of lawsuits is being filed against individuals who illegally download movies through sites like Napster and BitTorrent.

In 2011, the U.S. Copyright Group initiated “the largest illegal downloading case in U.S. history” at the time, suing over 23,000 file sharers who illegally downloaded Sylvester Stallone’s movie, The Expendables. This case was expanded to include the 25,000 users who also downloaded Voltage Pictures’ The Hurt Locker, which increased the total number of defendants to approximately 50,000 who used peer-to-peer downloading through BitTorrent. The lawsuits are filed based on the illegal downloads made from an IP address.

Digital books are also now in play. In 2012, a lawsuit was filed in China against technology giant Apple for sales of illegal book downloads through the App Store. Nine Chinese authors are demanding payment of $1.88 million for unauthorized versions of their books that were submitted to the App Store and sold to consumers for a profit. Again, the individual IP addresses are the primary way of determining who performed the illegal download. Telecom providers and their customers face privacy concerns, as companies are being asked for the names of customers associated with IP addresses identified with certain downloads.

Privacy activists argue that an IP address (which identifies the subscriber but not the person operating the computer) is private, protected information that can be shown during criminal but not civil investigations. Fred von Lohmann, senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, has suggested on his organization’s blog that “courts are not prepared to simply award default judgments worth tens of thousands of dollars against individuals based on a piece of paper backed by no evidence.”

Instructions: (1) Each student team individually adopts either the Point or CounterPoint argument and justifies their reasons (arguments using this case and other evidence/opinions). (2) Then, either in teams or designated arrangements, each shares their reasons. (3) The class is debriefed and insights shared.

POINT: File sharing is theft, and endangers the entire structure of incentives that allows the creation of digital media. Downloading even one song illegally has severe costs for the musicians and the owners and employees of the companies that produce songs, and legitimate online music services, not to mention consumers who purchase music legally. Those responsible, even peripherally, for illegal file sharing should be tracked down by any means possible and held accountable for these costs and damages.

COUNTERPOINT: The generation that grew up with the advent of digital media has a well-cultivated expectation of ease and freedom when it comes to accessing music, television, and books using the Internet. Companies are willing to capitalize on that ease to boost their profits. It is unethical to use technology and the legal system to “make examples” of those (possibly innocent bystanders whose IP addresses were used by others) who are simply showing the flaws and gaps in distribution strategies.

SOURCES

The exercise was authored by Taya Weiss and draws on the following sources:

Brian, M. (January 7, 2012). Apple facing $1.88 million lawsuit in China over sales of illegal book downloads. http://thenextweb.com/apple/2012/01/07/apple-facing-1-88-million-lawsuit-in-china-over-sales-of-illegal-book-downloads/, accessed March 7, 2012.

Kravets, David. (March 18, 2013). Supreme Court OKs $222K verdict for sharing 24 songs. Wired.com. http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2013/03/scotus-jammie-thomas-rasset/, accessed January 8, 2014.

Kirk, Jeremy. (2008). U.S. judge pokes hole in file-sharing lawsuit. Court ruling could force the music industry to provide more evidence against people accused of illegal file sharing, legal experts say. InfoWorld.com. http://www.infoworld.com/article/08/02/26/US-judge-pokes-hole-in-file-sharing-lawsuit_1.html, accessed March 7, 2012.

McMillan, G. (May 10, 2011). Are you one of 23,000 defendants in the U.S.’ biggest illegal download lawsuit? Time.com. http://techland.time.com/2011/05/10/are-you-one-of-23000-defendants-in-the-us-biggest-illegal-download-lawsuit/, accessed March 7, 2012.

Pepitone, J. (June 10, 2011). 50,000 BitTorrent users sued for alleged illegal downloads. CNNMoney.com. http://money.cnn.com/2011/06/10/technology/bittorrent_lawsuits/index.htm, accessed March 7, 2012.

Recording Industry Association of America. (March 2008). New wave of illegal file sharing lawsuits brought by RIAA. RIAA.com. http://www.riaa.com/newsitem.php?news_year_filter=2004&resultpage=10&id=D119AD49-5C18-2513-AB36-A06ED24EB13D, accessed March 7, 2012.

von Lohmann, F. (February 25, 2008). RIAA File-Sharing Complaint Fails to Support Default Judgment. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2008/02/riaa-file-sharing-complaint-fails-support-default-judgment, accessed February 19, 2014.

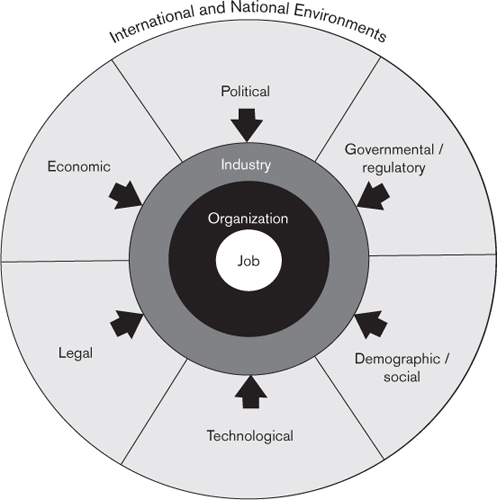

Environmental Forces and Stakeholders

Organizations and individuals are embedded in and interact with multiple changing local, national, and international environments, as the above discussion illustrates. These environments are increasingly merging into a global system of dynamically interrelated interactions among businesses and economies. We must “think globally before acting locally” in many situations. The macro-level environmental forces shown in Figure 1.1 affect the performance and operation of industries, organizations, and jobs. This framework can be used as a starting point to identify trends, issues, opportunities, and ethical problems that affect people and stakes in different levels. A first step toward understanding stakeholder issues is to gain an understanding of environmental forces that influence stakes. As we present an overview of these environmental forces here, think of the effects and pressures each of the forces has on you.

Figure 1.1

Environmental Dimensions Affecting Industries, Organizations, and Jobs

The economic environment continues to evolve into a more global context of trade, markets, and resource flows. Large and small U.S. companies are expanding businesses and products overseas. Stock and bond market volatility and in-terdependencies across international regions are unprecedented, including the European market and the future of the euro, which is challenged by some defaulting economies. The rise of China and India presents new trade opportunities and business practices, if human rights problems can be solved in those countries. Do you see your career and next job being affected by this round of globalization?

The technological environment has ushered in the advent of electronic communication, online social networking, and near-constant connectivity to the Internet, all of which are changing economies, industries, companies, and jobs. U.S. jobs that are based on routine technologies and rules-oriented procedures are vulnerable to outsourcing. Online technologies facilitate changing corporate “best practices.” Company supply chains are also becoming virtually and globally integrated online. Although speed, scope, economy of scale, and efficiency are transforming transactions through information technology, privacy and surveillance issues continue to emerge. The boundary between surveillance and convenience also continues to blur. Has the company or organization for which you work used surveillance to monitor Internet use?

Electronic democracy is changing the way individuals and groups think and act on political issues. Instant web surveys broadcast over interactive web sites have created a global chat room for political issues. Creation of online communities in the 2004, 2008, and 2012 presidential campaigns have proved an effective political strategy for both U.S. parties’ fundraising programs and mobilizing of new voters. Have you used the Internet to participate in a national, local, or regional political process?

The government and legal environments continue to create regulatory laws and procedures to protect consumers and restrict unfair corporate practices. Since Enron and other corporate scandals, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and the revised 2004 Federal Sentencing Guidelines were created to audit and constrain corporate executives from blatant fraudulence on financial statements. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, whose mission is to protect consumers by carrying out federal consumer financial laws, educating consumers, and hearing complaints from the public, and more recently that Bureau has been functioning to help citizens with credit card abuses in particular.21

Several federal agencies are also changing—or ignoring—standards for corporations. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), for example, has sped up the required market approval time for new drugs sought by patients with life-threatening diseases, but lags behind in taking some unsafe drugs off the market.

Uneven regulation of fraudulent and anticompetitive practices affects competition, shareholders, and consumers. Executives from Enron and other large U.S. firms involved in scandals have been tried and sentenced. Should the banks that loaned them funds also be charged with wrongdoing? Should U.S. laws be enforced more evenly? Who regulates the regulators? The subprime lending crisis raises some of the same questions. Who can the public trust for advice about mortgages and substantial loans? Who is responsible and accountable for educating and constraining the public in such transactions in a democratic, capitalist society?

Legal questions and issues affect all of these environmental dimensions and every stakeholder and investor. How much power should the government have to administer laws to protect citizens and ensure that business transactions are fair? Also, who protects the consumer in a free-market system? These issues, which are exemplified in the file-sharing controversy as summarized in this chapter’s opening case, question the nature and limits of consumer and corporate laws in a free-market economy.

The demographic and social environment continues to change as national boundaries experience the effects of globalization and the workforce becomes more diverse. Employers and employees are faced with aging and very young populations; minorities becoming majorities; generational differences; and the effects of downsizing and outsourcing on morale, productivity, and security. How can companies effectively integrate a workforce that is increasingly both younger and older, less educated and more educated, technologically sophisticated and technologically unskilled?

In this book these environmental factors are incorporated into a stakeholder and issues management approach that also includes an ethical analysis of actors external and internal to organizations. The larger perspective underlying these analytical approaches is represented by the following question: How can the common good of all stakeholders in controversial situations be realized?

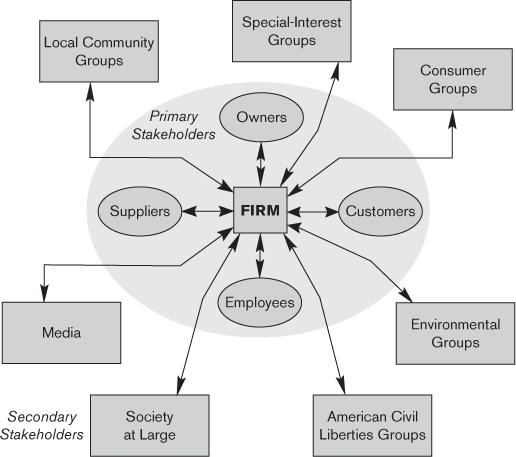

Stakeholder Management Approach

How do companies, the media, political groups, consumers, employees, competitors, and other groups respond in socially ethical and responsible ways when they effect and are affected by an issue, dilemma, threat, or opportunity from the environments just described? The stakeholder theory expands a narrow view of corporations from a stockholder-only perspective to include the many stakeholders who are also involved in how corporations envision the future, treat people and the environment, and serve the common good for the many. Implementing this view starts with understanding the ethical imperatives and moral understandings that corporations that use natural resources and the environment must serve, as well as providing for those who buy their products and services. This view and accompanying methods are explained in more detail in Chapters 2 and 3 especially and inform the whole text.

The stakeholder theory begins to address these questions by enabling individuals and groups to articulate collaborative, win—win strategies based on:

1. Identifying and prioritizing issues, threats, or opportunities.

2. Mapping who the stakeholders are.

3. Identifying their stakes, interests, and power sources.

4. Showing who the members of coalitions are or may become.

5. Showing what each stakeholder’s ethics are (and should be).

6. Developing collaborative strategies and dialogue from a “higher ground” perspective to move plans and interactions to the desired closure for all parties.

Chapter 3 lays out specific steps and strategies for analyzing stakeholders. Here, our aim is to develop awareness of the ethical and social responsibilities of different stakeholders. As Figure 1.2 illustrates, there can be a wide range of stakeholders in any situation. We turn to a general discussion of “business ethics” in the following section to introduce the subject and motivate you to investigate ethical dimensions of organizational and professional behavior.

Figure 1.2

Primary vs. Secondary Stakeholder Groups

1.2 What Is Business Ethics? Why Does It Matter?

Business ethicists ask, “What is right and wrong, good and bad, harmful and beneficial regarding decisions and actions in organizational transactions?” Ethical reasoning and logic is explained in more detail in Chapter 2, but we note here that approaching problems using a moral frame of reference can influence solution paths as well as options and outcomes. Since “solutions” to business and organizational problems may have more than one alternative, and sometimes no right solution may seem available, using principled ethical thinking provides structured and systematic ways of decision making based on values, not only perceptions that may be distorted, pressures from others, or the quickest and easiest available options—that may prove more harmful.

What Is Ethics and What Are the Areas of Ethical Theory?

Ethics derives from the Greek word ethos—meaning “character”—and is also known as moral philosophy, which is a branch of philosophy that involves “systematizing, defending and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct.”22 Ethics involves understanding the differences between right and wrong thinking and actions, and using principled decision making to choose actions that do not hurt others. Although intuition and creativity are often involved in having to decide between what seems like two “wrong” or less desirable choices in a dilemma where there are no easy alternatives, using ethical principles to inform our thinking before acting hastily may reduce the negative consequences of our actions. Classic ethical principles are presented in more detail in the next chapter, but by way of an introduction, the following three general areas constitute a framework for understanding ethical theories: metaethics, normative ethics, and descriptive ethics.23

Metaethics considers where one’s ethical principles “come from, and what they mean.” Do one’s ethical beliefs come from what society has prescribed? Did our parents, family, religious institutions influence and shape our ethical beliefs? Are our principles part of our emotions and attitudes? Metaethical perspectives address these questions and focus on issues of universal truths, the will of God, the role of reason in ethical judgments, and the meaning of ethical terms themselves.24 More practically, if we are studying a case or observing an event in the news, we can inquire about what and where a particular CEO’s or professional’s ethical principles (or lack thereof) are and where in his/her life and work history these beliefs were adopted.

Normative ethics is more practical; this type of ethics involves prescribing and evaluating ethical behaviors—what should be done in the future. We can inquire about specific moral standards that govern and influence right from wrong conduct and behaviors. Normative ethics also deals with what habits we need to develop, what duties and responsibilities we should follow, and the consequences of our behavior and its effects on others. Again, in a business or organizational context, we observe and address ethical problems and issues with individuals, teams, leaders and address ways of preventing and/or solving ethical dilemmas and problems.

Descriptive ethics involves the examination of other people’s beliefs and principles. It also relates to presenting—describing but not interpreting or evaluating—facts, events, and ethical actions in specific situations and places. In any context—organizational, relationship, or business—our aim here is to understand, not predict, judge, or solve an ethical or unethical behavior or action.

Learning to think, reason, and act ethically helps us to become aware of and recognize potential ethical problems. Then we can evaluate values, assumptions, and judgments regarding the problem before we act. Ultimately, ethical principles alone cannot answer what the late theologian Paul Tillich called “the courage to be” in serious ethical dilemmas or crises. We can also learn from business case studies, role playing, and discussions on how our actions affect others in different situations. Acting accountably and responsibly is still a choice.

Laura Nash defined business ethics as “the study of how personal moral norms apply to the activities and goals of commercial enterprise. It is not a separate moral standard, but the study of how the business context poses its own unique problems for the moral person who acts as an agent of this system.” Nash stated that business ethics deals with three basic areas of managerial decision making: (1) choices about what the laws should be and whether to follow them; (2) choices about economic and social issues outside the domain of law; and (3) choices about the priority of self-interest over the company’s interests.25

Unethical Business Practices and Employees

The seventh (2011) National Business Ethics Survey (NBES), which obtained 4,800 responses representative of the entire U.S. workforce,26 reported an ethical environment unlike any we have seen before in America: “American employees are doing the right thing more than ever before, but in other ways employees’ experiences are worse than in the past.”27 The survey findings are summarized below in terms of the “bad” and “good” news found in the workforce:

The “Bad” News

• Retaliation is on the rise against employee whistle-blowers, with 22% of employees who reported misconduct experiencing some form of retaliation.

• More employees (13%) feel pressure to compromise their ethical standards in order to do their jobs.

• The number of companies with weak ethical cultures has grown to near-record highs, now at 42%.

The “Good” News

• The workplace is experiencing the lowest levels of misconduct, with only 45% of employees witnessing misconduct.

• A record high (65%) of those employees now report misconduct.

• Management is improving its oversight and increasing efforts to raise awareness about ethics—34% of employees felt more closely watched by management, and 42% of employees recognized increased ethical awareness efforts.

The authors of the survey note that an ethical downturn is on the horizon. The economic decline and high unemployment have created a unique ethical environment fueled by other modern factors like social networking. “Research has revealed a significant ethics divide between those who are active on social networks and those who are not.”28

Specific Types of Ethical Misconduct Reported

The top five most frequently observed types of misconduct were: misuse of company time (33%), abusive behavior (21%), lying to employees (20%), company resource abuse (20%), and violating company Internet use policies (16%). Types of misconduct with the largest increases included: sexual harassment, substance abuse, insider trading, illegal political contributions, stealing, and environmental violations.29

Many employees still do not report misconduct that they observe, and fear of retaliation is increasingly valid. “When all employees are asked whether they could question management without fear of retaliation, 19 percent said it was not safe to do so.” The most common forms of retaliation include: exclusion by management from decision and work activity (64%), cold shoulder attitudes from other employees (62%), verbal abuse from management (62%), not given promotions or raises (55%), and cut pay or hours (46%). This retaliation can lead to instability in the workplace by driving away talented employees. “About seven of 10 employees who experienced retaliation plan to leave their current place of employment within five years.”30

Ethics and Compliance Programs

Ethical components of company culture include: “management’s trustworthiness, whether managers at all levels talk about ethics and model appropriate behavior, the extent to which employees value and support ethical conduct, accountability and transparency.” Eleven percent of companies in 2011 had weak ethical cultures. Companies can reduce ethics risks by investing in a strong ethics and compliance program: “86% of companies with a well-implemented ethics and compliance program also have a strong ethics culture.”31

The Retaliation Trust/Fear/Reality Disconnect

Of the 65% of employees who reported witnessing misconduct in the 2011 NBES, 22% (or approximately 9 million employees) experienced retaliation. These victims of retaliation are far more likely to report misconduct to an outside source, rather than to a member of management. This can have many negative consequences for stakeholders involved.32

Reporting rates are much higher in companies that have well-implemented ethics and compliance programs; only 6% of employees in companies with strong ethics and compliance programs did not report observed misconduct.

It is interesting to note the impact of social networking on the ethical environment of a company. According to the 2011 NBES:

• “Active social networkers report far more negative experiences of workplace ethics. As a group, they are almost four times more likely to experience pressure to compromise standards and about three times more likely to experience retaliation for reporting misconduct than co-workers who are less active with social networking. They also are far more likely to observe misconduct.” Seventy-two percent of active social networkers surveyed observed misconduct; 42% felt pressure to compromise standards; and 56% experienced retaliation after reporting misconduct.

• Active social networkers, as discussed in this chapter’s opening case, are also more likely to believe that questionable behaviors are acceptable. Forty-two percent of active social networkers felt that it was acceptable to blog or tweet negatively about their company or colleagues; 42% felt that it was acceptable to buy personal items on a company credit card as long as it was paid back; 51% felt it was acceptable to do less work as payback for cuts in pay or benefits; 50% felt it was acceptable to keep a copy of confidential work documents in case you need them in your next job; and 46% felt that it was acceptable to take a copy of work software home for use on their personal computer. Only about 10% of non-active social networkers felt that these activities were acceptable.33 Are you an active social networker? Do these results resonate with you?

These findings suggest that any useful definition of business ethics must address a range of problems in the workplace, including relationships among professionals at all levels and among corporate executives and external groups.

Why Does Ethics Matter in Business?

“Doing the right thing” matters to firms, taxpayers, employees, and other stakeholders, as well as to society. To companies and employers, acting legally and ethically means saving billions of dollars each year in lawsuits, settlements, and theft. One study found that the annual business costs of internal fraud range between the annual gross domestic profit (GDP) of Bulgaria ($50 billion) and that of Taiwan ($400 billion). It has also been estimated that theft costs companies $600 billion annually, and that 79% of workers admit to or think about stealing from their employers. Other studies have shown that corporations have paid significant financial penalties for acting unethically.34 The U.S. Department of Commerce noted that “as many as one-third of all business failures annually can be attributed to employee theft.” Experts have estimated that approximately 40% of fraud and theft losses to American businesses are internal.35

Relationships, Reputation, Morale, and Productivity

Costs to businesses also include deterioration of relationships; damage to reputation; declining employee productivity, creativity, and loyalty; ineffective information flow throughout the organization; and absenteeism. Companies that have a reputation for unethical and uncaring behavior toward employees also have a difficult time recruiting and retaining valued professionals.

Integrity, Culture, Communication, and the Common Good

Strong ethical leadership goes hand in hand with strong integrity. Both ethics and integrity have a significant impact on a company’s operations. “‘History has often shown the importance of ethics in business – even a single lapse in judgment by one employee can significantly affect a company’s reputation and its bottom line.’ Leaders who show a solid moral compass and set a forthright example for their employees foster a work environment where integrity becomes a core value.”36 A study of the 50 best companies to work for in Canada (based on survey responses from over 100,000 Canadian employees at 115 organizations, with input from 1,400 leaders and human resources professionals) found that integrity and ethics matter in the following ways: there is more flexibility and balance; values have changed; and organizations are valuing new employees more since the demographics have changed.37 These changes are explained next.

Integrity/Ethics

What is the degree to which coworkers, managers, and senior leaders display integrity and ethical conduct? Eighty-eight percent of employees at the top 10 best employers agreed or strongly agreed that coworkers displayed integrity and ethical conduct at all times, whereas only 60% felt that way at the bottom 10 organizations. With respect to managers, the numbers were 90% at the top 10 and 63% at the bottom 10 organizations. A bigger difference existed with regard to whether senior leadership displayed integrity and ethical conduct at all times, with 89% of employees at the top 10 best employers agreeing or strongly agreeing, whereas less than half—48%—felt that way at the bottom 10 employers.38

The same study found that “engagement is higher at organizations where employees feel they share the same values as their employer” and that “sense of ‘common purpose’ can increase employee commitment, especially amongst older workers.” The authors also noted that “a perceived lack of integrity on the part of co-workers, managers and leaders has, as expected, a detrimental effect on engagement. What was perhaps unanticipated in the study findings, however, was the really negative opinion of the ethics of senior leadership at low-engagement organizations.”

Working for the Best Companies

Employees care about ethics because they are attracted to ethically and socially responsible companies. Fortune magazine regularly publishes the 100 best companies for which to work (http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/best-companies).39 Although the list continues to change, it is instructive to observe some of the characteristics of good employers that employees repeatedly cite. The most frequently mentioned characteristics include profit sharing, bonuses, and monetary awards. However, the list also contains policies and benefits that balance work and personal life and those that encourage social responsibility. Consider these policies described by employees:

• When it comes to flextime requests, managers are encouraged to “do what is right and human.”

• There is an employee hotline to report violations of company values.

• Managers will fire clients who don’t respect its security officers.

• Employees donated more than 28,000 hours of volunteer labor last year.

The public and consumers benefit from organizations acting in an ethically and socially responsible manner. Ethics matters in business because all stakeholders stand to gain when organizations, groups, and individuals seek to do the right thing, as well as to do things the right way. Ethical companies create investor loyalty, customer satisfaction, and business performance and profits.40 The following section presents different levels on which ethical issues can occur.

1.3 Levels of Business Ethics

Because ethical problems are not only an individual or personal matter, it is helpful to see where issues originate, and how they change. Business leaders and professionals manage a wide range of stakeholders inside and outside their organizations. Understanding these stakeholders and their concerns will facilitate our understanding of the complex relationships between participants involved in solving ethical problems.

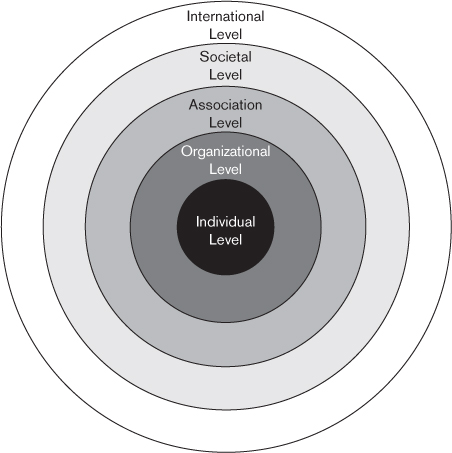

Ethical and moral issues in business can be examined on at least five levels. Figure 1.3 illustrates these five levels: individual, organizational, association, societal, and international.41 Aaron Feuerstein’s now classic story as former CEO of Malden Mills exemplifies how an ethical leader in his seventies turned a disaster into an opportunity. His actions reflected his person, faith, allegiance to his family and community, and sense of social responsibility.

On December 11, 1995, Malden Mills in Lawrence, Massachusetts—manufacturer of Polartec and Polarfleece fabrics and the largest employer in the city—was destroyed by fire. Over 1,400 people were out of work. Feuerstein stated, “Everything I did after the fire was in keeping with the ethical standards I’ve tried to maintain my entire life, so it’s surprising we’ve gotten so much attention. Whether I deserve it or not, I guess I became a symbol of what the average worker would like corporate America to be in a time when the American dream has been pretty badly injured.” Feuerstein announced shortly after the fire that the employees would stay on the payroll while the plant was rebuilt for 60 days. He noted, “I think it was a wise business decision, but that isn’t why I did it. I did it because it was the right thing to do.”

Figure 1.3

Business Ethics Levels

Source: Carroll, Archie B. (1978). Linking business ethics to behavior in organizations. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 43(3), 7. Reprinted with permission from Society for Advancement of Management, Texas A&M University, College of Business.