99 TO 1

1 Coming Apart at the Middle

An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal

ailment of all republics.

—Plutarch (c. 46–120 CE)

For more than three decades, the United States has undertaken a dangerous social experiment: How much inequality can a democratic self-governing society handle? How far can we stretch the gap between the super-rich 1 percent and everyone else before something snaps?

We have pulled apart. Over a relatively short period of time, since the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, a massive share of global income and wealth has funneled upward into the bank accounts of the richest 1 percent—and, within that group, the richest one-tenth of 1 percent.

This has been not just a U.S. trend but a global tendency, as the wealthiest 1 percent of the planet’s citizens delinked from the rest of humanity in terms of wealth, opportunity, life expectancy, and quality of life.

The New Grand Canyon: Extreme Inequality

There has always been economic inequality in the world and within the United States, even during what is called the “shared prosperity” decades after World War II, 1947 to 1977. But since the late 1970s, we’ve entered into a period of extreme inequality, a dizzying reordering of society.

This radical upward redistribution of wealth was not a weather event but a human-created disaster. Segments of the organized 1 percent lobbied politicians and pressed for changes in the rules in the political area, rules governing such areas as trade, taxes, workers, and corporations. In a nutshell: (1) the rules of the economy have been changed to benefit asset owners at the expense of wage earners, and (2) these rule changes have benefited global corporations at the expense of local businesses. There has been a triumph of capital and a betrayal of work.

The story of the last three decades is that working hard and earning wages didn’t move you ahead. “Real income”—excluding inflation—has remained stagnant or fallen since the late 1970s. Meanwhile, income from wealth (such as investments, property, and stocks) has taken off on a rocket launcher. Today, the dirty secret about how to get very wealthy in this economy is to start with wealth.

Most Americans are aware, on some level, that the rich have gotten steadily richer. We’ve seen the reports about mansions being torn down to build new mega-mansions. Or the CEOs who are paid more in one day than their average employees earn in a year. We’ve watched the middle-class dream collapse for ourselves or loved ones around us. We’ve intuitively sensed a shift in the culture toward individualism and the celebration of excessive wealth while also witnessing an erosion of the community institutions that we all depend on, such as schools, libraries, public transportation, and parks.

The Inequality Chat Room

Meanwhile, the public conversation over inequality has slowly progressed since 1980. In the late 1980s, the main debate was over whether inequality existed at all. Pundits and scholars squabbled over the data. Kevin Phillips, a former speechwriter for President Richard Nixon, wrote a book called The Politics of Rich and Poor that decried the first stage of income inequality in the 1980s.

1

Others countered that his facts were wrong or disputed his methodology.

2

By 2000, however, there was a strong consensus about the facts of income inequality. Speeches by conservatives Alan Greenspan and President George W. Bush decried the troubling trends in income disparity.

3

The public disagreement shifted to a dispute over what caused these inequalities and whether they mattered at all. Most agreed that poverty—inadequate income, lack of resources, and social exclusion—is a problem. But does it matter how wealthy the wealthy are? Does the concentration of wealth matter to the larger society?

This is where the debate has remained stalled for many years. Some analysts argue that inequality doesn’t matter as long as there is mobility, opportunity, and poverty alleviation. And some believe inequality is good because it motivates people at the bottom of the economic ladder to work harder.

Most of us have been too busy to monitor the changing trends in the economy. Some of us have been on a financial treadmill, working harder and running faster to stay in the same place. Or we’ve lost ground, watching our dreams of future economic stability slip away. The real inequality story has crept up on most of us while we weren’t looking.

A Tolerance for Inequality

Now we’re waking up. Attitude polls indicate that people are much more alarmed about wealth inequality and the destruction it has wreaked upon our economic lives.

The United States has historically had a very high tolerance for inequality compared to the rest of the world. For decades, the majority attitude toward stories of excessive wealth was “So what?”

4

Prior to 2008, polls reflected that a majority of Americans, while troubled by growing inequality, believed that income inequality was a result of varying degrees of individual merit. In other words, people’s economic status was a reflection of deservedness—hard work, intelligence, and effort. Most people were not troubled by the fact that a small sliver of people was becoming fantastically wealthy—as long as that wealth was fairly attained and that others had the same opportunity in terms of social mobility.

But since 2008, public attitudes have shifted. The middle-class standard of living has imploded, with once stable families now experiencing economic insecurity. And intergenerational mobility in the United States—the promise that the circumstances of one’s children will likely be better than one’s own—is now lower than in other industrialized countries. A greater percentage of the public now believes that the lopsided distribution of wealth is a problem. More people view great fortunes as the result of the wealthy 1 percent rigging the rules of the game in their favor.

5

Even with growing unease over inequality, the issue has remained sequestered from public debate. The policy debates in Washington, D.C., appear disconnected from the real concerns of ordinary Americans. For example, the U.S. Congress appears preoccupied with matters such as the national debt and debt ceiling, rather than deep unemployment, home foreclosures, corporate tax dodging, and the collapse of the middle class.

Most of us have felt powerless to change these growing inequality dynamics and the reckless and shortsighted actions of the powerful. This is, in part, because most of the corporate media that dominates our airwaves didn’t think inequality was a topic worthy of much public scrutiny or discussion.

Until recently. Thanks to protesters occupying Wall Street and the “99 percent” movement across the world, the conversation began to shift. And even as protests morph into new forms, a fundamental change in attitudes is under way.

Media analysis during the summer and fall of 2011 found that media attention shifted away from a focus on debt to a focus on unemployment, inequality, and Wall Street.

6

By October 2011, two-thirds of the public believed wealth should be more evenly distributed and that Congress should reverse tax cuts for corporations and increase income taxes on millionaires.

7

These feelings about inequality are unlikely to change in coming years. People’s deep anger has been given credence. The eloquent personal statements appearing at places such as the We Are the 99 Percent website give expression to the suffering, pain, insecurity, and anger that have been invisible for far too long. There is no going back.

The simple demand that we should have an economy that works for everyone, not just the richest 1 percent, is powerful, resonant, and inspiring.

The current political system, dominated by the concerns of the top 1 percent and captured by a small segment of global corporations, is incapable of responding to demands for greater shared prosperity. And so the pressure will continue to build for real change.

The 99 Percent Movement

At the Occupy Wall Street protests, an early hand-lettered protest sign stated, WE ARE THE 99 PERCENT. Soon a website emerged, with individuals writing their “we are the 99 percent” stories.

8

One military veteran wrote that she had friends die for this country and is grateful not to have student loans. But her fiancé will have over $75,000 in loans.

I am a licensed practical nurse with no job prospects. I haven’t been employed in over a year… . I couldn’t get a job as a waitress as I was overqualified. I am the 99%.

9

Another young woman writes that she is unable to save for her February wedding because she’s working in a restaurant busing tables for $8 an hour to help her father pay off $23,000 in student loans and medical bills.

I want to start a family someday, but the future looks dim.

I’m not even 20 years old yet and I already feel like debt will consume my whole life. I am the 99%.

“We are the 99 percent” has become the rallying cry for a new way of looking at the economy. Through the lens of 99 versus 1, we can ask questions such as: Will this policy help the bottom 99 percent? Is this politician a servant of the 1 percent? Which side are you on?

The First Gilded Age: 1890–1929

The history of inequality in the last hundred years reveals that our nation previously lived through a period of extreme inequality and reversed those trends, thanks in part to people coming together to press for change. Understanding this history will help us roll back the current chapter of inequality we are living through.

The last time U.S. society experienced such extreme levels of inequality was during the long Gilded Age from 1890 to 1928. In the aftermath of the industrial revolution, wealth inequalities became glaring and stark.

The great robber baron fortunes, those of Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Vanderbilt, exercised tremendous economic, political, and cultural power. And a handful of giant corporations—what a century ago were called “concentrations” and “trusts”—dominated the political system with their short-term interests.

Scholars estimate that around 1929, the wealthiest 1 percent owned as much as 44 percent of all private wealth, compared to about 36.5 percent today.

10

Equally alarming was the rate of corporate consolidation and the formation of monopolies, especially in railroads, banking, and heavy industry such as steel production. Between 1897 and 1904, some 4,227 firms consolidated into 257 companies.

11

Historian James Huston observed that “in a wave of pools, trusts, and then mergers, large business enterprise took over the core production of the American economy. The change induced a panic mentality among commentators who feared that now the distribution of wealth was becoming permanently warped and unsuitable for republican institutions.”

12

During this first Gilded Age there was a robust debate about the consequences of inequality. Social commentators, religious leaders, and industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie rang the alarm about the threat that concentrated wealth and power posed to our democracy, economy, and culture. They believed it shattered all the ideals upon which the U.S. experiment in self-governance was founded.

13

Journalist Henry Demarest Lloyd characterized the era as “wealth against commonwealth,” with the corrosive power of concentrated wealth undermining the larger common good. After the American Revolution, which eliminated the hereditary rule of monarchy, the United States was now dangerously close to becoming a plutocracy—a society ruled by its wealthy elite. Exposés of the period documented the almost complete capture of the U.S. Senate by wealthy and corporate interests.

14

At the time, a young Louis Brandeis stated, “We can have concentrated wealth in the hands of a few or we can have democracy. But we cannot have both.”

15

Being in the bottom 99 percent in 1910 undoubtedly was bleak. It must have seemed at the time that the concentrations of wealth and power were unchangeable. It would have been almost impossible to envision back then that the next generation would live in a flowering period of relative equality and shared prosperity.

The extended Gilded Age ended in 1929, in part because of the Great Depression and two world wars. But a significant factor was that popular movements and political leaders rebelled against the corrosive impact of extreme inequality. Religious leaders, urban workers, rural populists and farmers, and civic-oriented politicians were champions of fundamental rule changes and reforms.

16

These reformers pressed for policies to reduce concentrated wealth and broaden prosperity. They advocated for rule changes such as passage of the federal income tax and estate tax in 1916 with the explicit goal of reducing income and wealth concentrations.

17

Other rule changes included legislation banning child labor, breaking up corporate monopolies (trust busting), expanding corporate regulation, and instituting social expenditures to address poverty and poor housing conditions.

These changes had the positive impact of greatly reducing wealth disparities. The share of wealth owned by the 1 percent dropped from 44 percent in 1929 to 20 percent in 1970.

18

Growing Together: The Years of Shared Prosperity, 1947–1977

The shared prosperity in the years after World War II was the result of rule changes made between 1930 and the 1960s that focused on expansion of the middle class, not on enriching the 1 percent. Some economists called this period of relative equality the “great compression” because of the ways that U.S. society equalized out.

19

Policy Changes That Reversed the First Gilded Age

Why did this happen? Part of the reason was the collapse of fortunes during the Great Depression. But, equally important, our society advanced a two-part pro-equality agenda that reduced wealth concentrations and promoted expansion of the middle class.

Pro-Middle-Class Agenda. The rules of the economy were organized to promote the expansion of a middle class, particularly among white households. Tax revenue was invested in expanding educational opportunity, homeownership, and infrastructure.

• Expansion of free higher education. Programs such as the GI Bill provided debt-free college educations to more than 11 million returning veterans between 1945 and 1955. Benefits went beyond military veterans to include additional groups via Pell Grants, other educational grants, and low-interest loans.

• Homeownership expansion. Government programs aimed at boosting homeownership, such as the Farmers Home Administration, Federal Housing Administration mortgage insurance, and housing loans provided through the Veterans Administration, provided low fixed-rate mortgages for terms as long as forty years. Between 1945 and 1968 the percentage of the U.S. population that became home-owners expanded from 44 percent to 63 percent. This investment put a generation of homeowners on the road to wealth building.

20

Reducing the concentration of wealth. Emerging out of the Great Depression, a number of policies were boldly aimed at reducing the concentration of wealth and corporate power.

• Taxing high incomes and wealth. In 1916, Congress instituted both progressive inheritance taxes and high income taxes. Over a generation, this greatly reduced wealth disparities and also raised revenue to pay for the middle-class agenda.

• Oversight and taxing of corporations. Corporations were brought under considerably more public oversight after the Depression and were required to contribute tax revenue to the war effort and the building of society’s infrastructure.

• Boosting labor power in relation to Wall Street power. Rules were changed to permit greater worker organization, which gave workers a greater voice in the economy.

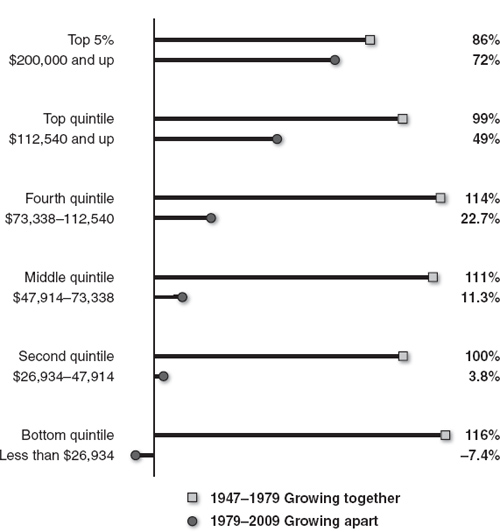

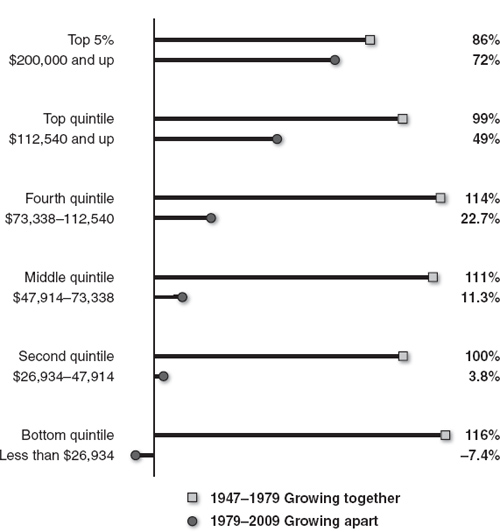

These rule changes resulted in widely shared prosperity across all segments of U.S. society. In the thirty years after World War II, from 1947 to 1977, real income growth was seen across the economic spectrum. The highest-income 1 percent saw their incomes rise during this period at the same rate as the rest of the society. The rising tide lifted almost all boats across the society, particularly for whites and men.

Figure 1. Growing together after World War II and pulling apart after 1979.

There’s an important historical lesson and political point here. We have reversed extreme inequality that existed once before in U.S. history. Because these inequalities are human-made, they are not impermeable to change.

Pulling Apart: 1977 to Present

The “growing together” years after World War II were a stark contrast to the “pulling apart” period of unequal growth of income and wealth over the last thirty-five years. In coming chapters, we will explore the reasons extreme inequality has grown. But part of the story is simple: the rules governing the economy were tilted to benefit the wealthiest 1 percent at the expense of the 99 percent, and to benefit the top Wall Street corporations at the expense of Main Street businesses.

Starting in the late 1970s, as many large U.S. corporations established global assembly lines, real wages for much of the U.S. population began to stagnate. For the bottom 20 percent, real wages actually declined between 1976 and 1990.

These dismal wage trends would have been worse if not for two factors that masked their real impact. The first was the increasing number of hours worked per household, especially with more women entering the paid labor force. This meant that some households could maintain their standard of living in the face of rising health care and housing costs, even as real wages declined.

21

The second factor was easy access to credit. Households in the bottom 80 percent borrowed heavily to fill in for declining or stagnant wages. They utilized credit cards and high-interest consumer loans, paying interest rates over 20 percent in some cases. If they owned a home, they often borrowed against the equity in their property.

22

For millions of households, wage stagnation and falling wealth resulted in greater poverty and job insecurity. For others, debt and overwork fueled a vast illusion of middle-class affluence, as consumption expanded even as wages fell. People bought new cars and flat-screen TVs and went to Red Lobster for dinner. But this middle-class consumption was based on working more hours and borrowing, not on real wage growth. As we shall see, this sowed the seeds for the economic meltdown of 2008.