Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Bedtime Stories for Managers

Farewell to Lofty Leadership. . . Welcome Engaging Management

Henry Mintzberg (Author)

Publication date: 02/05/2019

The moral here is this: managers need to leave their castles and find out what's actually going on in their kingdoms. And like real bedtime stories, these essays have metaphors galore. So prepare to grow strategies like weeds and organize like a cow. Discover the maestro myth of managing, find the soft underbelly of hard data, and learn why downsizing is bloodletting and your board should be a bee. Mintzberg writes, “Just try not to be outraged by anything you read, because some of my most outrageous ideas turn out to be my best. They just take a while to become obvious.”

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

The moral here is this: managers need to leave their castles and find out what's actually going on in their kingdoms. And like real bedtime stories, these essays have metaphors galore. So prepare to grow strategies like weeds and organize like a cow. Discover the maestro myth of managing, find the soft underbelly of hard data, and learn why downsizing is bloodletting and your board should be a bee. Mintzberg writes, “Just try not to be outraged by anything you read, because some of my most outrageous ideas turn out to be my best. They just take a while to become obvious.”

ONE

Stories of Managing

Big things and little things are my job. Middle-level arrangements can be delegated.

—Kōnosuke Matsushita, founder of Panasonic

Managing Scrambled Eggs

One morning years ago, I flew Eastern Airlines from Montreal to New York. It was the largest airline in the world at the time but was soon to go belly-up.

They served food in those days, well, sort of—something they called “scrambled eggs.” I said to the flight attendant: “I’ve eaten some awfully bad things on airplanes, but this has to be the worst.”

“I know,” she replied. “We keep telling them; they won’t listen.”

How can this be? If they were running a cemetery, I could understand the difficulties of communicating with the customers. But an airline? Whenever I encounter awful service or a badly designed product, I wonder if the management is running the business or reading the financial statements.1

The financial analysts were certainly reading those statements—and probably explaining the airline’s problem in terms of load factors and the like. Don’t believe a number of it. Eastern Airlines went belly-up because of those scrambled eggs.

Some years later, after telling this story to a group of managers, one of them, from IBM, came up to tell me another story: The CEO of Eastern Airlines came rushing in at the last minute for a flight, he said. First class was full, so they bumped a paying customer to put the CEO where I guess he had become accustomed. Apparently feeling guilty, he reportedly made his way to economy class. (No mention was made of his having to ask where it was.) There he apologized to the customer and introduced himself as the CEO of the airline. The customer replied: “Well, I’m the CEO of IBM.”

Now, don’t get this wrong. The problem was not about who was bumped. Quite the contrary. Status was the problem: higher class counted for more than common sense. Managing is not about sitting where you have become accustomed. It’s about eating the scrambled eggs.

The Maestro Myth of Managing

Picture the managerial maestro on the podium: a flick of the baton and marketing opens; a wave of the wand and sales chimes in; a grand sweep of the arms and HR, PR, and IT harmonize. It’s a manager’s dream—you can even attend leadership workshops orchestrated by conductors.2

Here are three quotes about this metaphor. As you read them, we’ll play a little game. Please vote for which quote best captures your understanding of managing. But there’s a trick: you must vote after you read each, before you have read any other. There is, however, a compensating trick: you can vote up to three times!

From Peter Drucker, the guru’s guru:

One analogy [for the manager] is the conductor of a symphony orchestra, through whose effort, vision and leadership individual instrumental parts that are so much noise by themselves become the living whole of music. But the conductor has the composer’s score: he is only interpreter. The manager is both composer and conductor.3

Your vote for the manager as composer and conductor? From Sune Carlson, a Swedish economist who carried out the first serious study of managerial work of Swedish CEOs:

Before we made the study, I always thought of a chief executive as the conductor of an orchestra, standing aloof on his platform. Now I am in some respects inclined to see him as the puppet in the puppet-show with hundreds of people pulling the strings and forcing him to act in one way or another.4

Your vote for the manager as puppet?

From Leonard Sayles, who studied middle managers in the United States:

The manager is like a symphony orchestra conductor, endeavoring to maintain a melodious performance … while the orchestra members are having various personal difficulties, stage hands are moving music stands, alternating excessive heat and cold are creating audience and instrumental problems, and the sponsor of the concert is insisting on irrational changes in the program.5

Your vote for the manager in rehearsal?

I have used this game with many groups of managers. The results are always the same: a few hands might go up for the first and a few more for the second, but when I read the third, all the hands go up! Managers are like orchestra conductors, all right, but away from performance, to the everyday grind. Beware of metaphors that glorify.

As for orchestra conductors, are they managers at all, even leaders? Outside of performance, certainly both, together. They select the musicians and the music and, during rehearsals, blend them into a coherent whole. But watch a conductor in performance: it is mostly that—performance. Better still, watch the musicians during performance: they barely look at the conductor—who, by the way, may be a guest conductor. Can you imagine a guest manager anywhere else?6

Who is pulling the strings: Toscanini or Tchaikovsky? Actually, the musicians do that, but each plays the notes written for their instrument by the composer, all together. So it is the composer who is both composer and conductor. But since the composers are dead, the conductors get the acclaim.

Maybe all the world really is a stage, with all the composers, conductors, managers, and players merely players. If so, no manager belongs on the podium of lofty leadership.

Managing to Lead

The fable that leadership is separate from, and superior to, management has been bad for management and worse for leadership.

The fashionable depiction sees leaders as doing the right things while managers do things right.7 This may sound right, until you try to do the right things without doing them right.

John Cleghorn, as CEO of Royal Bank of Canada, developed a reputation in his company for calling the office on his way to the airport to report a broken automatic-teller machine. This bank had thousands of such machines. Was he micromanaging? No, he was leading by example. Some of the best leadership is management practiced well.

Have you ever been managed by someone who didn’t lead? That must have been awfully discouraging. Well, how about having being led by someone who didn’t manage? That person may have been just plain disconnected: how could they know what was going on? As Jim March of the Stanford business school put it: “Leadership involves plumbing as well as poetry.”8

So let’s get past leadership dissociated from management, to recognize that these are two sides of the same job. Haven’t we had enough of leading by remote control, disconnected from everything except the “big picture”? In truth, the big picture has to be painted with the little brushstrokes of grounded experience.

You may have heard that we are overmanaged and underled. Now it’s the opposite: we have too much lofty leadership and not enough engaging management. Here is a comparison of the two. Take your choice.

Two Ways to Manage

|

Lofty Leadership |

Engaging Management |

|

1. Leaders are important people, quite apart from others who develop products and deliver services. |

1. Managers are important to the extent that they help other people be important. |

|

2. The higher “up” these leaders go, the more important they become. At the “top” the CEO is the organization. |

2. An effective organization is an interacting network, not a vertical hierarchy. Effective managers work throughout; they don’t sit on some top. |

|

3. Down the hierarchy goes the strategy—clear, deliberate, and bold—emanating from the chief, who takes the dramatic acts. Everyone else “implements.” |

3. Out of the network emerge strategies, as engaged people solve little problems that can grow into big strategies. |

|

4. To lead is to make decisions and allocate resources—including those Human Resources. Leadership thus means calculating, based on facts, from reports. |

4. To manage is to connect naturally with human beings. Managing thus means engaging, based on judgment, rooted in context. |

|

5. Leadership is thrust upon those who thrust their will on others. |

5. Leadership is a sacred trust earned from the respect of others. |

Selecting the Flawed Manager

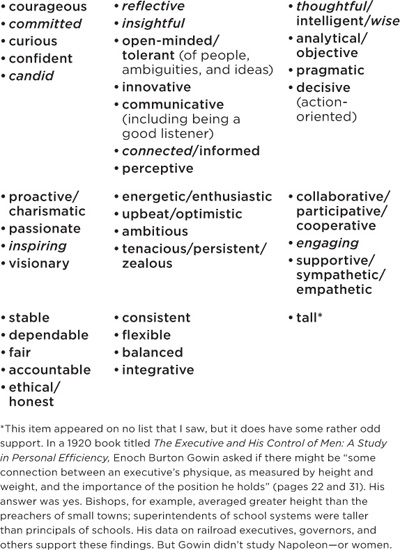

What makes a manager/leader effective?9 The answer awaits you in all sorts of little lists. For example, a University of Toronto Executive MBA brochure listed:

• The courage to challenge the status quo

• To flourish in a demanding environment

• To collaborate for the greater good

• To set clear direction in a rapidly changing world

• To be fearlessly decisive

The trouble with these little lists is that they are never complete. For example, where on this one is basic intelligence or being a good listener? Fear not—these qualities appear on other lists. So I made a comprehensive list from all the little lists I could find, adding a few favorites of my own. As you can see in the table at the story’s end, it contains 52 qualities. Be all 52 and you are bound to be a terribly effective manager—even if not a human one.

The Inevitably Flawed Manager

All of this is part of our romance with leadership that puts ordinary mortals on pedestals (“Rudolph is the perfect person for the job: he will save us!”), and then allows us to vilify them as they come crashing down (“How could Rudolph have failed us so?”). Yet some managers do stay up, if not on that precarious pedestal. How so?

The answer is simple: successful managers are flawed—everyone is flawed—but their particular flaws are not fatal under the circumstances. Reasonable human beings find ways to live with one another’s reasonable flaws.

Fatally flawed are those utopian lists of managerial qualities because they can be awfully wrong. Can anyone disagree about managers needing to be “fearlessly decisive”? For starters, those who watched George W. Bush lead (but not manage) the American march into Iraq. He certainly had “the courage to challenge the status quo” (if not the bad advice of his advisers). Ingvar Kamprad managed IKEA as it became one of the most successful retail chains ever. It reportedly needed 15 years to “set clear direction in a rapidly changing world.” Actually, it succeeded because the furniture world was not changing rapidly; IKEA changed it.

Choosing the Devil You Had Better Get to Know

If everyone’s flaws come out sooner or later, then sooner is better, especially for managers. In fact, managers should be selected for their flaws as much as for their qualities. Unfortunately, we tend to focus on the qualities, often just one: “Sally’s a great networker” or “Rudolph’s a visionary,” especially if the failed predecessor was a lousy networker or devoid of strategic vision.

There are really only two ways to know a person’s flaws: marry them or work for them. But how many among the people who select the managers—board members for chief executives, superior managers for subordinate ones (what awful terms)—have ever worked for the candidates, let alone been married to them? As a consequence, too many of their choices end up being “kiss up and kick down” people: smooth-talking and overconfident, great at impressing “superiors” but nasty in managing “subordinates.”

People who select managers have to hear from the people who know the candidates best. Now, they can’t exactly ask the candidates’ spouses because the current ones will be biased and the former ones will be more biased. But they can certainly get the opinions of the people who have been managed by these candidates.

I’m not one for magic bullets in management, but if one prescription could improve the practice of managing monumentally, here it is: give voice in selection processes to people who have been managed by the candidates. Please sleep on this bedtime story.

Composite List of Basic Qualities for Assured Managerial Success

Compiled from various sources; my own favorites are in italics.

The Epidemic of Managing without Soul

My daughter Lisa once left me a note in a shoe that read, “Souls need fixing.” Little did she know.

A Tale of Two Nursing Managers

When we asked the incoming participants of our International Masters for Health Leadership (IMHL) program to share stories about their experiences, an obstetrician told about the time when, as a resident, he was shuttling between the wards of several hospitals. He and his colleagues “loved working” in one of them. It was a “happy” place, thanks to a head nurse who cared. She was understanding, respectful of everyone, and intent on promoting collaboration between doctors and nurses. The place had soul.

Then she retired and was replaced by a nurse who had an MBA. Without “any conversation … she started questioning everything.” She was strict with the nurses, sometimes arriving early to check who might come late. Where there used to be chatting and laughing at the start of shifts, “it became normal for us to see one nurse crying” because of some comment by the new manager.

Morale plummeted, and soon that spread to the physicians: “It took two to three months to destroy that amazing family.… We used to compete to go to that hospital; [subsequently,] we didn’t want to go there anymore.” Yet “the higher authority didn’t intervene or maybe was not aware” of what was going on.

How often have you heard such a story—or lived one? (In one week I heard four.) And no few are about CEOs. Managing without soul has become an epidemic in society. The worst of it is mean-spirited, bullying people by playing them off against one another.

A Hotel with Soul

Sometime after, I was in England for a meeting at one of those corporate hotels—no spirit, no soul, high turnover of staff, the usual. Then Lisa and I headed up to the Lake District to check out a hotel for one of our programs.

I walked in and fell in love with the place. Beautifully appointed, perfectly cared for, a genuinely attentive staff—this hotel was loaded with soul. I have been studying organizations for so long that I can often sense soul, or lack of it, in an instant. I feel the energy of the place, or the lethargy; the genuine smile instead of the grin from a “greeter”; honest concern instead of “Customer Service.”

“What’s it mean to have soul?” Lisa asked.

“You know it when you see it,” I replied, “in every little corner.” I asked a waiter about hiking trails. He didn’t know, so he fetched the manager of the hotel, who explained them all in detail. I chatted with a young woman at reception. “The throw pillows on the bed are really beautiful,” I said.

“Yes,” she replied, “the owner cares for every detail—she picked those pillows herself.”

“How long have you been here?” I asked.

“Four years,” she answered proudly and then rattled off the tenures of the senior staff: the manager 14 years, the assistant manager 12 years, the head of sales a little less.

Why can’t all organizations be like this? Most people—employees, customers, managers—want to care, given half a chance. We human beings have souls, so why not our hospitals and hotels? Why do we build great institutions only to let them wither under people who should never be allowed to manage anything? Souls need fixing all right—and so does a lot of managing.

Five Easy Steps for Managing without Soul

Here are the only five easy steps you will find in this book. Any one will do.

• Manage the bottom line, as if you make money by managing money, rather than attending to products, services, and customers.

• Make a plan for every action—no spontaneity please, and no learning.

• Move managers around so that they can never get to know anything well but management (after a fashion).

• Hire and fire those Human Resources the way you buy and sell other resources.

• Do everything in five easy steps.

How about doing everything with five alert senses?

Managing in the Age of the Internet

Fundamentally, managing does not change. It’s a practice rooted in art and craft, not a science or a profession based on analysis. The subject matter of managing may change, but the effective practice does not.

Does this mean that the new digital technologies, especially email, haven’t changed the basic practice of managing? Yes, except in one particular respect: by intensifying the characteristics that have long prevailed in practice, they are throwing too much of it over the edge.

The Characteristics of Managing

As I found in my own initial research, managing is a hectic job: fast-paced, high-pressured, action-oriented, frequently interrupted. In the words of one chief executive, managing is “one damn thing after another.”10 The job is also largely oral: managers do a lot more talking and listening than reading and writing. And they do this communicating laterally as much as hierarchically: most managers spend at least as much time with people outside their units as with those inside. All of this is not bad managing; it is normal managing.

The Impact of the Internet

How, then, do the new digital technologies, especially email, affect this?

Maya, managing

• One thing seems certain: the capacity to communicate instantly with people everywhere increases the pace and pressure of managing—and likely the interruptions as well. If you’ve got mail, you’d better answer it right away. But don’t be fooled. Even before the internet, there was evidence that managers chose to be interrupted. Now more do so by checking messages at every little ping! and replying immediately. One corporate CEO told an interviewer: “You can never escape. You can’t go anywhere to contemplate or think.” Not true: you can go anywhere you please.

• Internet connectivity has intensified managers’ orientation to action: everything is expected to be faster, immediate. How ironic that a technology literally removed from the action—picture a manager facing a screen—exacerbates the action orientation of managing. With all those electrons flying about, the hyperactivity gets worse. (If you are reading this bedtime story on a Sunday evening, check your email because your boss—or you!—may have just called a meeting for Monday morning.)

• Of course, more time reading on the screen and writing on the keyboard means less time talking and listening to people face-to-face. There are only so many hours in every day. How many more of them are you now devoting to such reading and writing, instead of being with the staff, or the kids, or getting some decent sleep (after reading this story)?

• Email is limited to the poverty of words alone. There is no tone of voice to hear, no gesture to see, no presence to feel. Yet managing depends on this kind of information too. On the telephone people laugh or grunt; in meetings they nod in agreement or nod off in distraction. Astute managers pick up on these signals.

• Of course, email has made it easier to keep “in touch” with a wide network of contacts all over the world. But how about colleagues down the hall? Does sitting in front of a screen put you out of touch with them?

A senior government official I met boasted that he kept in touch with his staff through email early every morning. In touch with a keyboard perhaps, but with his staff?

These fast-paced characteristics of managing are normal only within limits. Exceed them at your own risk. The devil of the new technologies can be found in the details: when hectic becomes frenetic, a manager can lose control of the job and become a menace to the organization. The internet, by giving the illusion of control, may in fact be robbing many managers of control over their own work.

Thus this digital age may be driving much management practice over the edge, making it too remote and superficial. So don’t let the new technologies manage you: Don’t allow yourself to be mesmerized by them. Understand their dangers as well as their delights so that you can manage them. Turn them off. Sweet dreams!

Do We Really Live in Times of Great Change?

When a CEO sits down at a laptop to prepare a speech, the machine automatically types: “We live in times of great change.” That’s because just about every such speech over the past 50 years has started with this claim. That never changes.

Do we really live in times of great change? Look around and tell me what’s changed fundamentally. Your food, your furniture, your friends, your fixations? Are you wearing a tie or high heels? Why, other than because you always have? How about the engine of your car?

It probably has the basic technology that was in the Model T Ford. When you dressed this morning, did you say to yourself: If we live in times of such great change, how come we are still buttoning buttons? (The kind of buttons we use appeared in Germany in the thirteenth century.)

What’s my point? That we notice only what is changing, and most things are not. Sure, we notice the internet. (Zap, I hit a few keys and Wikipedia tells me about the origin of buttons.) But try to notice all the things that are not changing, because to manage change without managing continuity is anarchy.

Decision-Making: It’s Not What You Think

… It’s also what you see

How do we make decisions? That’s easy. First we diagnose, next we design (possible solutions), then we decide, and finally we do (carry the choice into action). In other words, we think in order to act: I call this thinking first.

Consider probably the most important decision of your life: finding your mate. Did you think first? Using this model, let’s say as a male in search of a female mate, first you make a list of what you are looking for, say, brilliant, beautiful, and bashful. Then you list all the possible candidates. Next comes the analysis: you score each candidate on all the criteria. Finally, you add up all the scores to find out who has won, then inform the lucky lady.

Except that she informs you that “While you were going through all this, I got married and now have a couple of kids.” Thinking first does have its drawbacks.

So chances are you proceeded in a different way, like my father, who announced to my grandmother, “Today I met the woman I’m going to marry!” There was not a lot of analysis in this decision, I assure you, but it worked out well—a long and happy marriage ensued.

This is known as “love at first sight.” As a model of decision-making, I call it seeing first. You might be surprised how many important decisions get made this way—for example, deciding to hire someone two seconds into an interview, or buying a facility because you like the look of the place. These are not necessarily whims; they can be insights.

But not so fast: there’s another, often more sensible way to make decisions. I call it doing first. I’ll leave how that works in finding a mate to your imagination. Suffice it to say that, when you’re not sure how to proceed—for decisions both big and small—you may have to do in order to think, instead of think in order to do. You try something, in a limited way, to see if it might work; if it doesn’t, you try something else, until you find something that works, and then do more of it. Start small to learn big.

Of course, this has its drawbacks too. As Terry Connolly, a professor interested in decision-making, quipped, “Nuclear wars and childbearing decisions are poor settings for a strategy of ‘try a little one and see how it goes.’”11 But there are lots of other decisions for which this can be a perfectly good approach. Paint a product blue: next thing you know, you may be selling a rainbow of colors.

So, do you have an important decision to make? Good. Hold those thoughts. Tomorrow, look around! Do something! You may find yourself thinking differently.12

Growing Strategies Like Weeds in a Garden

In need of a strategy? Here’s how, stylized a little from just about every book and article on the subject.

So neatly lined up (Photo by Henry Mintzberg)

The Hothouse Model of Strategy Formulation

1. There is one prime strategist, and that person is the chief executive officer—the planter of all strategies. Other managers may fertilize, while consultants offer advice (sometimes even the strategy itself—but don’t tell anybody).

2. Planners analyze the appropriate data so that the CEO can formulate the strategy through a controlled process of conscious thought, much as tomatoes are cultivated in a hothouse.

3. The strategy comes out of this process immaculately conceived, then to be made formally explicit, much as ripe tomatoes are picked and sent to market.

4. This explicit strategy is then implemented, which includes developing the necessary budgets as well as designing the appropriate structure—the hothouse for the strategy. (If the strategy fails, “implementation” is blamed, namely those dumbbells who were not smart enough to implement the CEO’s brilliant strategy. But be careful, because if those dumbbells are smart, they will ask: “Why, if you are so smart, did you not formulate a strategy that we dumbbells were capable of implementing?” You see, every failure of implementation is also a failure of formulation.)

5. Hence, to manage this process is to plant the strategy carefully and watch over it as it grows on schedule so that the market can beat a path to its produce.

Wait, don’t go off and start formulating your strategy quite yet. Read the next model first.

So wonderfully organic

A Grassroots Model of Strategy Formation

1. Strategies grow initially like weeds in a garden; no need to cultivate them like tomatoes in a hothouse. They can form, rather than having to be formulated, as decisions and actions taken one by one amalgamate into a consistent pattern. In other words, strategies emerge gradually through a process of learning. The hothouse, if need be, can come later.

2. These strategies can take root in all kinds of curious places, wherever people have the capacity to learn and the resources to support that capacity. Anyone in touch with an opportunity can come up with an idea that can evolve into a strategy. An engineer meets a customer and imagines a new product. No discussion, no planning—she just builds it. The seeds of a new strategy may have just been planted. The point is that organizations cannot always plan where a strategy will begin, let alone plan the strategy itself. Accordingly, productive strategists build gardens in fertile ground, where all kinds of ideas can take root and the best of them can grow.

3. Individual ideas become strategies when they pervade the organization. Other engineers see what she has done and follow suit. Then the salespeople get the idea. Next thing you know, the whole organization has a new strategy—a new pattern in its activities—which might even come as a surprise in the C suite. After all, weeds can proliferate and encompass a whole garden; then the conventional plants can look out of place. But what is a weed but a plant that wasn’t expected? With a change of perspective, the emerging strategy can become what’s valued, much as Europeans enjoy salads of the leaves of dandelions, America’s most notorious weed.

4. Of course, once an emerging strategy is recognized as valuable, its proliferation can be managed, the way plants are selectively propagated. An emergent strategy becomes a deliberate strategy going forward. Managers just have to appreciate when to exploit an established crop of strategies and when to encourage new strains to replace them.

5. Hence, to manage this process is not to plan or plant strategies but to recognize their emergence and intervene when appropriate. A truly destructive weed, once noticed, has to be uprooted immediately. But one that may be capable of bearing that fruit can be worth watching, in fact sometimes worth pretending not to notice until it bears that fruit or else withers. Then hothouses can be built around those that offer the hanging fruit, low or high.

Okay, now you are all set for strategy, by forgetting the word and doing a lot more learning than planning.13