CHAPTER 1

Believe-in-You Money

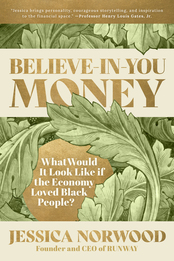

The first time I used the term “Believe-in-You Money” was during a keynote session I was facilitating for a conference on local economies in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was November 2015, and snow was coming down heavily. I opened the session with a story about the city’s Black business legacy. I believe in calling on the histories of Black business owners as a way of acknowledging the long-standing legacy of and fight for equal opportunity. Their life stories provide me with language that enables me to give voice to the problems that Black owners face in service of moving forward. As you read this book, you’ll encounter stories that animate the experiences of Black entrepreneurs. In my keynote speech that day in Cincinnati, I told the story of Henry Boyd.

Henry Boyd was born an enslaved person on a Kentucky plantation in 1802.1 When he was 24, he arrived in Cincinnati, a free state, as a skilled carpenter and woodworker. Hoping to find work, he applied for jobs but was turned down when White workers threatened to leave if Boyd was hired. One day, when one of the White carpenters came to work drunk, Boyd took on the work and impressed the owner. Soon, he was contracted for more projects, and word began to spread about Boyd’s talent. Over time, Boyd made enough money to purchase the freedom of his brother and sister.

With a growing number of customers, Boyd purchased a woodworking shop and began creating a new design for a bed frame, the Boyd Bedstead. The beds were sturdy and had railing that was both decorative and functional. But because of racial discrimination, he was unable to get a patent for his design. In 1833, a White cabinetmaker named George Porter was issued the patent for Boyd’s designs. It’s not known if Porter and Boyd worked together to secure the patent, but we do know that Boyd was a unique businessman. The H. Boyd Company was integrated with both White and Black men working together, and his popularity was such that prominent Cincinnatians of the time purchased his bed frames.

By 1855, the H. Boyd Company had expanded to include a showroom and took up several storefronts downtown. However, Boyd’s vision of a fully integrated company was not welcomed by everyone. His business was burned down twice, and in 1862—with no companies willing to insure him—Boyd closed his doors for good. Despite being well known in abolitionist circles for his contributions as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, Boyd died with no remarkable fanfare and was buried in an unmarked grave.2

When I stepped offstage after sharing the story of Henry Boyd, Oscar Perry Abello, a journalist who covers local economics and power building, asked me what made me share Boyd’s story. I told him that what happened to Boyd—the economic discrimination and violence—is still happening to Black companies today. Part of the reason for this is the persistent discrimination that created and continues to expand the wealth gap. Oscar and I talked about the ongoing sabotage that these owners are subjected to, often over many generations. “How do you change that?” he asked. I said, “We need to invest as if we care about the people and about the places they come from. We need Believe-in-You Money.”

A few months after this exchange, Oscar published a story about my efforts to provide friendly, nonexploitative capital to Black founders as a form of repair for the racial discrimination they continue to face. When the piece went to print, I didn’t yet have the language to name precisely what I was calling for. But over time I arrived at the term “Believe-in-You Money” to describe my proposal for a new approach that provides business capital in a way that can support the repair of racial injustice.

What Is Believe-in-You Money?

Believe-in-You Money is nonextractive,

patient capital that is explicitly antiracist.

It is not “venture capital, but make it Black.” Believe-in-You Money is something different. It’s community centered, rooted in storytelling and rituals of care and kinship. This kind of money is held by women in small villages in El Salvador as well as by giving circles in Birmingham, Alabama. This money is everywhere. The people who move this money are in sou sous, which are informal savings communities throughout the African diaspora, online on crowdfunding sites, in boardrooms, or sitting with their wealth manager. This money is drawn to the power of the people. This money makes you feel good. This money makes you feel seen. This money finds joy in the success of others. This money sees our shared humanity. This kind of money is an energy—the Ase of life itself— and has been moving between peoples for a millennium.

Believe-in-You Money is a commitment to providing Black founders and creators flexible, nonburdensome money at the beginning of their capital experience. It could be considered an intentional alternative to conventional friends-and-family capital because it’s explicitly antiracist and nonextractive, but the spirit of the idea is the same. Believe-in-You Money can be in the form of gifts, grants, patient debt, revenue share, convertible equity, and other forms I have not thought of. The goal of the capital is to shift power and to build trust, mutual support, and respect.

Believe-in-You Money is the answer when we want to pour into one another in a way that provides an additional source of power to move forward. Perhaps you have received this kind of money or just instinctively understand the intentions. Believe-in-You Money is capital that is nonextractive; patient, long-term; and antiracist. These descriptors are discussed below.

1. Nonextractive

Nonextractive capital broadly represents the belief that the money invested should benefit the founders more than the investor. Nonextractive terms can show up inside of the terms of repayment, interest rates, and risk management. Nonextractive finance can be used in loans, licensing, or royalty or future sales so long as the funds do not require the founder to give up equity. Nonextraction also means that repayment happens only when the company is able to cover operating expenses and when the business owner is able to pay themselves. In a nonextractive deal, security is based on the mission alignment and business preparedness of the company and a person’s relationships with the community instead of collateral or personal assets. Finally, and most importantly, nonextractive capital does not use credit scores but rather uses a character-based underwriting process that looks at multiple dimensions of the company and the company’s impact in the community.

2. Patient, Long-Term

There are many funds that already use patient or long-term capital strategies. In The Nature of Investing: Resilient Investment Strategies through Biomimicry, Katherine Collins talks about how biomimicry—applying the wisdom of nature to human systems— can inform our investing decisions.3 When we think about it, nature takes time to replenish and regenerate from a harvest or a major change in the environment, and if one were investing with nature, the return rate would be much slower, more harmonious, and interconnected to the people and the planet. These ideas are not new; they have been a part of Afro-Indigenous culture for a long time.

In the impact investing space, patient capital is often described as waiting a considerable amount of time—sometimes 10 years— before seeing a financial return. The idea behind patient capital is that by forgoing a quick return, we will get better social and environmental impact. Both the racial equity fund at RSF Social Finance and international lender Acumen use patient capital as a tool to support their investments.4 Investors use patient capital because they understand that these businesses have more barriers to overcome on their way to success. Funds that use long-term repayment schedules also tend to work in closer partnership with the business owner, providing technical support and access to key relationships and resources.

3. Antiracist

If you haven’t already, I strongly recommend you read How to Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi, who reminds us that the opposite of “racist” isn’t “not racist.” It is “antiracist.” Antiracism is all about the action that flows from the awareness of racism. In other words, now that you know about the racial wealth gap, what action are you going to take to dismantle it? Kendi says that to be an antiracist is to commit to undoing racism by constantly identifying it, describing it, and dismantling it. Believe-in-You Money puts this concept into motion by asking us to take action using different rules, procedures, and guidelines for investing in Black-founded start-up companies. Instead of being color-blind, we need to be explicitly antiracist. Kendi reminds us that there is no such thing as race-neutral or nonracist policy, and that in order to end the racial wealth gap, we will have to make policies that promote racial equity and are antiracist.

The 6 Characteristics of Believe-in-You Money

This book offers two pathways to ensure the success of Black business owners: one path to support personal change, and another path to ensure systems change. Personal change is about how we, the readers, can make changes in how we support Black companies. In the first half of the book, I share that if we want to help Black founders, we need to invest using nonextractive money, long-term money, and antiracist money. This kind of investment will have a personal impact on the founder that increases the possibility of their business surviving and thriving. It puts capital in their hands that’s much more reparative than what the market generally provides. But it does not change the system. For that, we need to talk about the six ways Believe-in-You Money can support systemic change.

The second half of the book is dedicated to going beyond investing in a Black founder alone to investing in the sustainability of Black-owned businesses and the ecosystem broadly. Chapters 4 through 9 introduce the six characteristics that can guide investment strategy, build power, and increase wealth in Black communities, using Black business investing as a starting strategy. I think these guiding characteristics are what make the difference. The systems change work is at the heart of what this book is aiming for—a revolutionary change in how we finance Black companies.

These chapters talk about the underlying values of Believe-in-You Money. You will quickly notice that each characteristic is a direct challenge to our current extractive system, and that is on purpose. I want us to see the current system; I want us to see what I am asking us to leave behind; and I want us to see what I’m inviting us to step into. I am asking us to leave behind an extractive economy in favor of a more loving and restorative economy. Ultimately, this is about “how we show up.” As you read, you may notice that some of the language will seem familiar, especially if you are in social justice movement spaces, because these characteristics are rooted inside those spaces too. I have learned to rely on the six characteristics in Believe-in-You Money as a compass on the road to repair. Working with these characteristics creates a new opportunity to be adaptive and unique—no more cookie-cutter ideas; this is about transformation.

In an effort to clearly articulate the characteristics of Believe-in-You Money and support greater understanding, I created the Believe-in-You Money Investing Chart, identifying the goals and attributes of Believe-in-You Money, contrasted with the symptoms of today’s extractive investing practices.

This chart is at the heart of the changes we could see when we use the ideas found in Believe-in-You Money. Black-owned businesses don’t need to be in a competition for scarce or time-sensitive funds; they need to be in community, with access to the financial support they need to thrive. True Believe-in-You Money follows those biblical words on love: love “believes all things.”

Believe-in-You Money Investing Chart

Money That Loves Black People |

Extractive Money |

Transformational relationships |

Transactional relationships |

Shared risk and the profit and reward go to the folks who did the work |

Risk-averse

Lion’s share of profits goes to investor

|

|

Restorative, mutually beneficial, accountable

Centering those harmed

|

Unequal power dynamics

Complicit in maintaining systems of oppression and harm

|

|

Promotes transparency and open communication

Confronts and releases shame and fear

|

Promotes secrecy, opacity, and unnecessary complication |

Impact made through interdependence, collective action, democratic processes |

Emphasizes individualistic, going-it-alone bootstrapping approach and reinforces the myth of meritocracy |

Regenerative, stable systems |

Exploitative, unstable systems |

Ask yourself whether your investments embody the identifiers from the chart:

1. Transformational relationships—Are we creating relationships that are based in truth-telling? Are we centering relationships that allow for transparency and vulnerability, learning and unlearning, and growth and education?

2. Shared risk—Are we recentering our understanding of risk by asking ourselves, What can’t we lose? This question focuses us on the things that matter: the workers, community well-being, and the planet.

3. Restorative and mutually beneficial—Have we created a space that addresses power dynamics and differences? Are we centering the experience of the founder rather than that of the investor? What does this look like when we have created spaces and conditions that are restorative and reparative?

4. Release shame and fear—Can we invite healing into this process? Is there a pathway to be courageous and open with our concerns? Can we create spaciousness to invite clarity over complication? Can we relax some of our ideas of process-heavy workloads with good communication, transparency, and grace?

5. Collective action—What does this look like if we emphasize community over the ideas of a single leader, which leads to founder burnout? How does our strategy unlock more collective power?

6. Regenerative systems—Did we build an ecosystem of support around the company and the community? Did we honor the cultural relationships that call for intersectional thinking? Are we building systems that allow people to thrive and that create sustainable places?

This list of characteristics can help you identify places where you can check in and evaluate the work. Questions like “Does this investment support collective action?” will help us determine whether we are doing personal change or systems change. It’s wise to revisit these concepts every so often to see if you are moving in alignment with your intentions. The truth is, we will need to be in process and in community about repairing racial harm for a lifetime. Just remember to embrace adaptation and give yourself grace. Remember that these six characteristics are about systems change, which is all about shifting attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs toward a new way of doing things. I am clear that I want to shift toward an economy that loves Black people. This is not Band-Aid work; if we commit to this, it will unlock and uplift the brilliance of Black people in a really special way.

In writing this book, I had the honor of talking to the legends in my life—leaders who manage funds, foundations, and financial institutions and who lead movements that build power and restore our soul. I spoke with seven friends, most of whom are Black women, with a White man and an Asian man in the mix too. Some of these individuals identify as queer. I asked them to talk to me about Believe-in-You Money in their lives, whether they’ve ever received this kind of support, and what it would mean to our community if others got it. We spent a lot of time talking candidly about race and power inside of money, with truth-telling as a recurring theme. I asked them what advice they would give to others who wanted to follow in their footsteps and invest Believe-in-You Money, and the answers were honest and profound. They all said in their own ways that we need to be doing our personal, internal work to undo racism in ourselves and in our systems. I am deeply grateful for the trust they have given me. Their ideas helped me understand what’s possible and unpack what has been holding us back, offering space to see the intersections of our relationships with wealth and racial equity. Together, we lift up a vision of transformation so powerful that I wish for all of us to hear it, invest in it, and experience it.