Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Building a Successful Social Venture

A Guide for Social Entrepreneurs

Eric Carlson (Author) | James Koch (Author)

Publication date: 09/18/2018

Building a Successful Social Venture draws on Eric Carlson's and James Koch's pioneering work with the Global Social Benefit Institute, cofounded by Koch at Santa Clara University's Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship. Since 2003, over 200 Silicon Valley executives have mentored more than 800 aspiring social entrepreneurs at the GSBI. It is this unparalleled real-world foundation that truly sets the book apart. Early versions of the book were used in both undergraduate and MBA classes.

Part 1 of the book describes the assumptions that the GSBI model is based on: a bottom-up approach to social change, a focus on base-of-the-pyramid markets, and a specific approach to business planning developed by the GSBI. Part 2 presents the seven elements of the GSBI business planning process, and Part 3 lays out the keys to executing it. The book includes “Social Venture Snapshots” illustrating how different organizations have realized elements of the plan, as well as a wealth of checklists and exercises.

Social ventures hold enormous promise to solve some of the world's most intractable problems. This book offers a tested framework for students, social entrepreneurs, and field researchers who wish to learn more about the application of business principles and theories of change for advancing social progress and creating a more just world.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Building a Successful Social Venture draws on Eric Carlson's and James Koch's pioneering work with the Global Social Benefit Institute, cofounded by Koch at Santa Clara University's Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship. Since 2003, over 200 Silicon Valley executives have mentored more than 800 aspiring social entrepreneurs at the GSBI. It is this unparalleled real-world foundation that truly sets the book apart. Early versions of the book were used in both undergraduate and MBA classes.

Part 1 of the book describes the assumptions that the GSBI model is based on: a bottom-up approach to social change, a focus on base-of-the-pyramid markets, and a specific approach to business planning developed by the GSBI. Part 2 presents the seven elements of the GSBI business planning process, and Part 3 lays out the keys to executing it. The book includes “Social Venture Snapshots” illustrating how different organizations have realized elements of the plan, as well as a wealth of checklists and exercises.

Social ventures hold enormous promise to solve some of the world's most intractable problems. This book offers a tested framework for students, social entrepreneurs, and field researchers who wish to learn more about the application of business principles and theories of change for advancing social progress and creating a more just world.

—Bill Drayton, CEO, Ashoka

“Jim Koch and Eric Carlson have drawn on more than a decade's experience with hundreds of social enterprise ventures working in communities around the world. From that rich database they have assembled a unique and valuable field-tested guide to business plan development that puts market-based approaches in service of social and developmental goals.”

—Dr. Al Hammond, serial social entrepreneur and principal author of The Next 4 Billion

“Rooted in Silicon Valley's entrepreneurial DNA, this practical guide will help social entrepreneurs build ventures that can scale their impact in serving the unmet needs of humanity and empower students with the knowledge and skills they need to transform their ideas into sustainable realities.”

—Dr. Thane Kreiner, Executive Director and Howard and Alida Charney University Professor, Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship, Santa Clara University

From Social Entrepreneurs:

“Where else can one find out how to go about developing a business plan with both impact and profit in mind? Where else does one find a guide to convert intractable social problems into opportunities for realistic dreamers to tackle through effective social ventures? Jim Koch and Eric Carlson's book Building a Successful Social Venture provides a powerful guide for social entrepreneurs like me, who must permanently battle the tradeoffs between social impact and sustainability. The book is a treasure.”

—Martin Burt, PhD, founder, Fundación Paraguaya (2005 Skoll Awardee), Poverty Stoplight, and Teach a Man to Fish

“The information found here is detailed and pertinent, with real-life insights into the origins and functioning of social enterprises. Step-by-step guidelines, examples, and charts offer a critical but encouraging perspective on building and scaling social impact.”

—Neelam Chibber, cofounder and Managing Trustee, Industree Crafts Foundation (2011 Social Entrepreneur of the Year India Awardee), and Schwab Fellow

“The term ‘social venture' has been notoriously ill-defined over the past decade. The authors bring much-needed definition to the space. This will be helpful for investors, regulators, and entrepreneurs alike going forward. At Kiva, we benefitted greatly from the Global Social Benefit Incubator in getting started. This work can help us take it to the next level!”

—Matt Flannery, cofounder and former CEO, Kiva (2008 Skoll Awardee), and cofounder and CEO, Branch.co

“The knowledge captured by the book is amazing. I wish we had a book like this for reference in 2002–03 when we went about setting up Ziqitza. Back then there was no concept of ‘social venture.' I believe this is a good foundation for anyone who is looking to start a social venture. Attending GSBI was a great experience for me; I learned so much in the short time I was on campus.”

—Ravi Krishna, cofounder and Director, Ziqitza Health Care (2013 Times of India Social Impact Awardee)

“A comprehensive guide and tool kit for these times. Koch and Carlson illuminate the field with research, case studies, and critical specification checklists. Their work makes it clear that social entrepreneurship has a vital role to play in the personal and collective transformation required to create a more harmonious and equitable world.”

—Ronni Goldfarb, founder and former President and CEO, Equal Access International (2016 Tech Awards Laureate)

“Carlson and Koch have written an informative guide that shows readers the unique opportunity that social entrepreneurship offers to address complex societal challenges and offers specific, engaging, and practical guidance for those of us eager to create financially sustainable and beneficial social ventures.”

—Sara Goldman, cofounder, Heart of the Heartland

“This book is the culmination of James Koch and Eric Carlson's dedication to mentoring hundreds of social enterprises, from formation through scale. There's never one right way to build a company, so they have aggregated and analyzed the different lessons learned from many organizations. This book is well worth the read for any aspiring or practicing social entrepreneur!”

—Lesley Marincola, founder and CEO, Angaza (2018 Skoll Awardee and 2016 Tech Awards Laureate)

“I have had the honor of learning many of the concepts presented in this book directly from Jim and Eric at Santa Clara. I applied many of these concepts at Husk Power Systems and raised funding to scale. This book does a phenomenal job of providing a very detailed and easy-to-follow framework for launching and scaling successful businesses focused on solving the world's biggest problems. Concrete case studies are presented in a succinct way to illustrate how these frameworks can be applied effectively. I would highly recommend both social entrepreneurs and successful social enterprises to read this book and use it as a reference to continually evolve.”

—Manoj Sinha, cofounder and CEO, Husk Power Systems (2009 and 2013 GSBI alumnus)

“An inspirational, holistic, and practical resource with real-world lessons and examples. A must-read for early stage ventures as well as ventures moving along the path to scale. I admire Jim and Eric's completeness of vision and their true and unwavering commitment to building social ventures and mentoring the social entrepreneurs who lead them.”

—Elizabeth Hausler, founder and CEO, Build Change (2017 Skoll Awardee)

From Undergraduate Beta Tests of Building a Successful Social Venture:

“University students hunger for effective theories of positive social change: Building a Successful Social Venture provides them a feast. Unlike most textbooks about social entrepreneurship, Building a Sucessful Social Venture challenges students to drill down into business models and how these can drive change in society. My students have drawn rich insights in enterprise-led social transformation from this book with direct application to action research projects around the world. Subsequent to using this book in two classes, four students received Fulbright Awards.”

—Keith Douglass Warner, OFM, Senior Director, Education and Action Research, and Director, Global Social Benefit Fellowship, Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship, Santa Clara University

From Santa Clara University MBA Students:

“I really enjoyed the class and definitely will be applying it to a future social venture I've wanted to create since I was much younger. Maybe I'll see you at the GSBI in a few years!”

—Bhargav Brahmbhatt

“This was by far my favorite class in the MBA curriculum. I've learned so much from the weekly assignments and roundtable discussions. I just developed my first ever business plan for work, which was a huge undertaking, and I would have been so lost without this course.”

—Erin Horiuchi

“It was a great learning experience for me and I am sure I will be using the concepts in my social venture.”

—Sijith Salim

“I thoroughly enjoyed the class, and I learned a lot about social entrepreneurship and MoringaConnect. It was a great experience working on a business plan for a real company with founders who are trying to make a real impact on the lives of farmers in Ghana. I will definitely take the lessons learned with me, and I hope to apply them throughout my career and personal life.”

—Brooke Langer

From Academic and Industry Experts:

“Complementing and extending prior Base of the Pyramid work, Carlson and Koch's book provides something new and important: a business planning paradigm designed specifically for the unique opportunities and challenges facing BoP entrepreneurs. The outcome is an entrepreneurs' roadmap for building better social ventures.”

—Ted London, Adjunct Professor, Ross School of Business & Senior Research Fellow, William Davidson Institute, University of Michigan, and author of The Base of the Pyramid Promise: Building Businesses with Impact and Scale

“This excellent workbook takes the reader through the steps in the process of developing and running a social venture. The examples are richly described and make the concepts come alive.”

—Madhu Viswanathan, PhD, Professor, Diane and Steven N. Miller Centennial Chair in Business, Founder of Subsistence Marketplace Initiative, Gies College of Business University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and author of Bottom-Up Enterprise: Insights from Subsistence Marketplaces.

“Carlson and Koch have crafted a rare primer that offers inspiration and guidance for every stage of the entrepreneurial journey. Building a Successful Social Venture shines as a text for undergraduate and graduate students of social innovation. The authors offer deep experiential wisdom and theory-driven frameworks built upon the practice of hundreds of social ventures. The stakes for social innovation are high for us all, and the authors place commendable emphasis on execution with a social consciousness—including actionable tools for investors, managers, and entrepreneurs who care about meaningful social change. This book is invaluable.”

—Geoffrey Desa, PhD, Associate Professor of Management and Social Innovation, San Francisco State University

“What a wonderful overview of the field with amazing tools for not only understanding conceptually but also moving the ideas of social innovation and social venture into practice.”

—Adrienne Falcon, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Public and Nonprofit Leadership, and Director, Master of Advocacy and Political Leadership, Metropolitan State University

“I feel very privileged to have been part of the first ten years of the Global Social Benefit Incubator at Santa Clara University in Silicon Valley—as a mentor, coach, friend, and teacher. In their book, Eric Carlson and James Koch brilliantly capture the lessons learned from the first ten years of their accelerator, informed by a unique combination of the Jesuit commitment to social justice and Silicon Valley's entrepreneurial and innovation-driven culture. This is a must-read for all social entrepreneurs serious about scaling their impact.”

—Charly Kleissner, PhD, cofounder, KL Felicitas Foundation, Toniic, 100% Impact Network, and Social-Impact International

“The authors have decades of experience on what it takes to build a social enterprise. It is no easy feat, and this book provides a detailed manuscript for entrepreneurs, with examples, exercises, and resources touching on each aspect of building a business. In the age of ‘fail fast,' this is a book on ‘build it to last.' The authors also trace the arc of shared experience and the original thesis behind creating social impact to guide both new enterprises and today's corporations in creating a better tomorrow.”

—John Kohler, Executive Fellow and Senior Director, Impact Capital, Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship, Santa Clara University

“Jim and Eric's book comes at a great time. Solving the world's toughest social issues—such as poverty, access to energy, health care, and education—has not occurred with top-down philanthropy. This “Guide for Social Entrepreneurs” simplifies that process of teaching social entrepreneurship from a bottom-up perspective. It is not an academic thought piece but rather draws from the experience of hundreds of social enterprises, both successful and unsuccessful; learning perhaps as much or more from the failures as from the successes. I highly recommend it.”

—Brad Mattson, Chairman, Siva Power; former Lead Mentor, GSBI; and founder and former CEO, Novellus and Mattson Technology

“This is the most practical and useful book for anyone thinking about developing a social venture that combines market-based principles with a social mission. Written by two authors who have deep experience working with hundreds of social ventures from around the world, every chapter, case study, and exercise is based on a solid foundation of lessons from more than a decade of experience with the GSBI program. This book is essential reading for social entrepreneurs, impact investors, and others interested in this sector.”

—Saurabh Lall, PhD, Assistant Professor of Social Enterprise and Nonprofit Management, School of Planning, Public Policy and Management, University of Oregon

“Professors Koch and Carlson have captured the essence of what has become the gold standard for social entrepreneur success and growth. With over ten years of practical implementation, involving hundreds of social entrepreneurs, they thoroughly detail the development of sustainable, scalable social business models and plans; clearly explain ‘bottom-up innovation through social ventures' and social change theory; and offer sound practical advice to overcome key challenges that all social entrepreneurs must deal with. I've been a social entrepreneur mentor for almost fifteen years, and this book is my number-one tool to accelerate the success of social businesses.”

—Dennis Reker, Lead Mentor, GSBI, and former senior executive, Intel

“From the perspective of someone who, in parallel with an international business career, has devoted more than fifty years to the development of bottom-up approaches to poverty reduction and social innovation, I find Building a Successful Social Venture by Eric Carlson and James Koch to be a magnificent contribution to this field and an invaluable handbook for those who wish to start, grow, fund, or evaluate a social venture—whether nonprofit or for-profit. This guide creates a historic and social context within which practitioners can better understand the significance of what they are doing, and it provides them with the tools they need to become effective at doing it. I believe it should be required reading for anyone who wants to change things for the better in a sustainable way.”

—Robert H. Scarlett, Board Chair, Venn Foundation; Trustee, Sundance Family Foundation; and Member, President's Circle, Accion

“The Miller Center at Santa Clara University has continued to be a source of rigorous and serious work with social entrepreneurs worldwide—contributing invaluable insights that have significantly influenced our own development and the field of social entrepreneurship. We believe that this new book based on the Santa Clara University experience will help thousands of entrepreneurs.”

—Alfred Vernis, Associate Professor of Business Policy and Strategy and cofounder, Institute for Social Innovation, ESADE Business School, ESADE–Ramon Llull University, Barcelona, Spain

“This fantastic resource sets a framework for social ventures as essential actors in the global economy. The middle part is the recipe: the how-to for social entrepreneurs. The beginning and end position social ventures as answers to needs in society and the economy that have not been, and arguably cannot be, addressed any other way. Social ventures are simultaneously a ‘new thing' in terms of their legitimacy in the eyes of academics and conventional businesspeople, and they're all around us. We all probably interact daily with, or may even already be part of, one, often without realizing it. This book illuminates the potential to improve the world in what we may already be doing and shows how we can do it even more powerfully. While newcomers to social entrepreneurship will find this an indispensable resource, it may be even more important for experienced social entrepreneurs because it will remind you of how mighty your work really is.”

—Sara Olsen, founder and CEO, SVT Group

1. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Theories of Social Progress

2. The Market at the Base of the Pyramid

3. Paradigms for Social Venture Business Plans

Part II: Managing a Sustainable/Scalable Social Business

4. Mission, Opportunity, Strategies

5. The External Environment

6. The Target Market Segment

7. Operations and Value Chain

8. Organization and Human Resources

9. Business Model

10. Metrics and Accountability

Part III: Execution

11. Operating Plan

12. Financing

13. The Path Forward

Chapter 1

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Theories of Social Progress

Pamela Hartigan began the 2012 Skoll World Forum with an eloquent recasting of a timeless nursery rhyme, lamenting our contemporary “Humpty Dumpty world.” In this world, “a good many of the king’s men are struggling to put Humpty back together again,” she said.1 As you may recall, things do not quite work out for Mr. Dumpty.

Even so, Hartigan went on to herald a “phase of new thinking and experimentation” where a growing group of people “with imagination, commitment, persistence, and strong ethical fiber is working furiously to ensure that Humpty Dumpty’s model is transformed and replaced with pathways that achieve economic and social justice and arrest the destruction of our planet.” Far from leaving Humpty in a heap—or to the king’s men to fix—Hartigan urged the forum to “seize this hugely important opportunity” and concluded with a provocative question: “How do we rewire our systems, our practices, and our mindsets so our story reflects a greater convergence rather than fragmentation of effort?”

In other words, how do we harness “the global movement of outrage on the part of ordinary citizens against an increasingly unfair and unsustainable society” and join it with “practical, creative, and committed social entrepreneurs” so that Humpty Dumpty is not simply recast the same as he was? For Hartigan, succeeding in this way is to ensure that when “our collective story is told, it will be about depicting the time that occurred when human ingenuity, empathy, and integrity rises to dominance together to address unprecedented threats.”

Our world is awash in urgent environmental, human, and social challenges. Many of them—the scourge of global poverty, for instance—are interdependent, dynamic, and seemingly intractable. What we know about how to solve them is far from complete. Not only are these global challenges urgent, but their scale is also growing at rates that appear beyond the capacity of our institutions to adapt. Are governments, philanthropic groups, large companies, and the independent sector equipped for the job? Perhaps not as they are.

Conceptual Roots

The conceptual foundations for this book are rooted in contexts of deep global poverty—contexts where scale matters. In the fifty years from 1962 to 2013, the world population grew from 3.2 billion to 7.1 billion, on a growth trajectory to reach 9.2 billion by 2050.2 Imagine our increasingly fragile planet tripling in population over the course of a single eighty-seven-year lifetime, from 1962 to 2050. Now visualize more than 95 percent of this growth concentrated in poor countries with accelerating rural to urban migrations. Imagine populations ballooning in cities like Beijing, Kolkata, and Mexico City, where millions of people are already choking in traffic congestion and air pollution, and where the combination of infrastructure and fiscal deficits renders governments incapable of meeting basic life-supporting necessities like safe water, sanitation, housing, education, and general public safety. In these contexts and others like them, the ability to develop solutions that can be replicated at scale is urgent.

Especially among refugees and youth trapped in generational poverty, it is little wonder that the world is experiencing unprecedented population migration from destitute rural areas to cities, and from the global south to the global north. Even so, the 2016 Social Progress Index, a major study of social well-being across 133 nations, illuminates what populations migrating in search of greater income opportunities will discover—namely, that geographic advantages in per capita income and human well-being are not synonymous. Just take a look at the United States. Ranked 5th in the world in GDP per capita, the United States ranks 27th out of 133 nations on the Social Progress Index for personal safety; 40th in access to basic knowledge, because too many kids are not in school; 36th in environmental quality due to greenhouse gas emissions, poor water quality, and threats to biodiversity; and 68th on health and wellness, despite outspending every nation in the world on its healthcare system.3 Over the past twenty-five years, U.S. gains in per capita income have become increasingly concentrated in the top 1 to 5 percent of the population. Median household incomes have stagnated, income inequality has grown, and the majority of citizens have not experienced improvements in quality of life. All of this contributes to nationalist instincts and pushback from citizens who see waves of immigrants as a source of downward pressure on working-class wages and competition for increasingly scarce opportunities to join the middle class.

In the United States, the poverty threshold for a family of four in 2015 was $24,257 per year, approximately $16.50 a day per person.4 In richer parts of the developing world, it is $4.00 a day per person. And, when purchasing power parity is taken into account, in extremely poor nations, it is $2.00 a day. At these income levels, the poor exist in a precarious state. Above these minimum thresholds, people may not appear in poverty counts, but they do not live in a world where, to paraphrase Nobel Prize–winning economist Amartya Sen, they have the freedom to make life choices that can significantly improve their hopes of a better future.5 With respect to the hope of achieving a middle-class standard of living, Thomas Piketty’s work on global capitalism has painted a pessimistic picture documenting unprecedented increases in income inequality and declining upward mobility over the last thirty years.6

Although in 2017 the eight richest people in the world owned more wealth than the 3.6 billion people in the bottom half of the world’s population,7 increasing wealth disparity is not unique to developing countries. The Pew Research Center finds income inequality in the United States at the highest level since 1928.8 After accounting for taxes and income transfers like social security, the United States is second only to Chile in terms of having the highest level of inequality in the world. Moreover, wealth inequality is even greater than income inequality. In 2013, the highest-earning one-fifth of U.S. families earned 59.1 percent of all income and held 88.9 percent of all wealth. Similarly, in China and India, inequality—as measured by the Gini coefficient (which measures the statistical distribution of incomes)—grew substantially between 1990 and 2015, from 0.45 to 0.51 in India and from 0.33 to 0.53 in China.9 A Gini coefficient of 0 indicates that citizens shared equally in national income, whereas a coefficient of 1.0 indicates perfect inequality, with one person receiving 100 percent of all income. As elsewhere, the inability of India and China to develop and sustain a rising middle class imperils future growth and social stability.

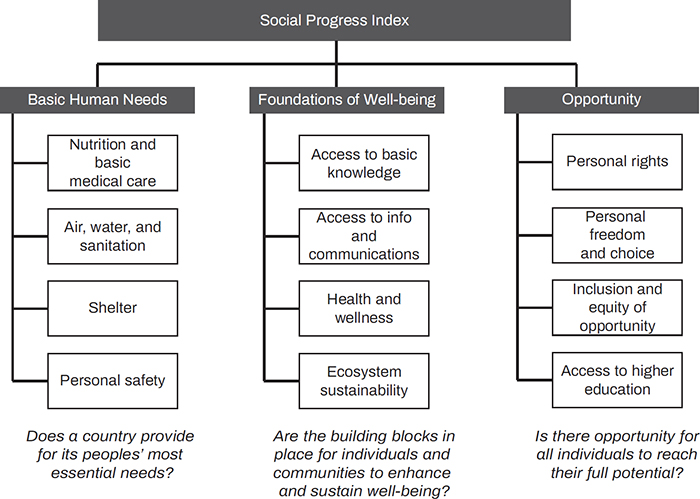

Figure 1.1 Social Progress Index

GDP growth alone does not ensure social progress or improved well-being of citizens—both of which often depend on the shifting priorities of governmental bodies. Reflecting Amartya Sen’s “development as freedom” philosophy, the Social Progress Imperative movement sees the world differently, as reflected in its Social Progress Index (SPI) in Figure 1.1. It posits a more complete assessment of national wealth—one that encompasses the capacity of a society to meet its citizens’ basic human needs, enhance and sustain the quality of their lives, and create the conditions for all individuals to reach their full potential.

While an in-depth examination of poverty is beyond the scope of this book, overall evidence of effective top-down solutions for fostering a more just world—be it in the form of government programs to alleviate poverty or trickle-down economic prosperity—is weak. We turn next to a brief examination of this evidence through a review of alternative approaches for eliminating poverty.

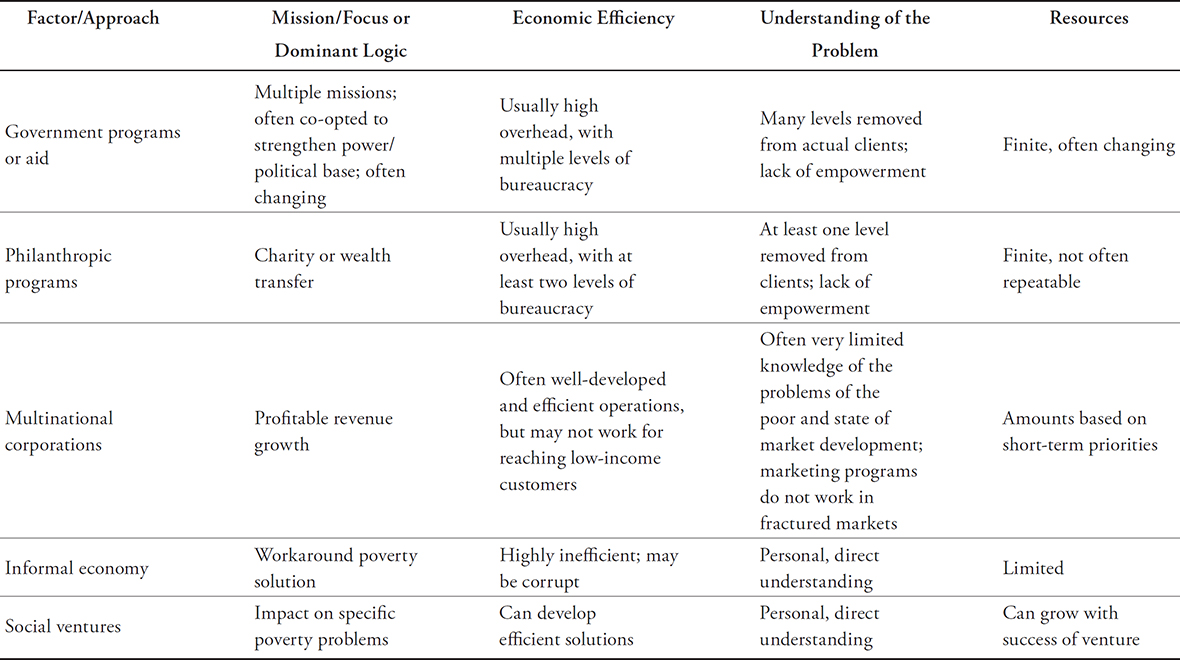

Comparing Approaches to Poverty Reduction

Since the end of World War II and the formation of the United Nations, several efforts have been mounted worldwide to help eliminate or reduce poverty. These efforts can be divided into five categories:

1. Government programs: National governments use tax revenues or subsidies and, in some instances, foreign aid to fund or operate programs

2. Philanthropy: Wealthy individuals create private foundations, charities raise money to fund or operate programs, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds support community initiatives

3. Multinational corporations: Large corporations use their resources and organization to enter and serve markets with unmet needs

4. The informal economy: A parallel system of economic exchange that, in some instances, uses illegal methods to address problems

5. Social ventures: Small organizations (both nonprofit and for-profit) focus on reducing poverty in a specific market segment

Figure 1.2 compares these five approaches to poverty reduction. We will now briefly review the first four poverty reduction approaches. The remainder of the chapter lays the foundation for the advantages of the fifth category, social ventures.

Government and Philanthropy

Although some consider government programs or aid and philanthropy to be distinct approaches to economic development, they are grouped together here because each is based on the assumption that, with adequate resources or external incentives, social systems can be changed from the outside. In the case of government, this perspective encompasses trickle-down theories of economic development, or the belief that macropolicy to stimulate economic growth will have trickle-down benefits to the well-being of those at the lowest rungs of society.10 In the case of global philanthropy, belief systems encompass a variety of meta-theories—each reflecting alternative models of what constitutes social progress and how best to achieve it in the minds of benefactors and their foundation entities. In either instance, critical resources needed for achieving social progress are externally controlled at higher institutional levels by the gatekeepers to public or private wealth.

Figure 1.2 Approaches to Poverty Reduction

Many economists and politicians, from J. K. Galbraith to Ross Perot and Bernie Sanders, have criticized trickle-down economics as an inefficient way to tackle urgent social needs. However, as with noteworthy success stories from the world of foundations, macropolicy can contribute to economic prosperity across economic strata. When the government invests directly in creating businesses (e.g., manufacturing in China) or accelerating the development of industry clusters in concentrated urban regions, it can have a substantial impact on economic development. For example, in China, the poverty level has dropped from around 80 percent under communism to around 40 percent under government-sponsored capitalism.11 Similarly, where government acts to stimulate capital formation in emergent technologies (e.g., Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency [DARPA] and advances in computer networking in the United States), significant and widely shared economic benefits can result. Even so, about 14 percent of the U.S. population (about forty-six million people) still lives below the poverty level, and a poverty rate of 40 percent in China equates to five hundred million people.12 In fact, the socialist approach to economic policy in Sweden fares no better when it comes to eliminating poverty, with 25 percent of Swedish citizens living in poverty.13

While targeted government programs and philanthropic initiatives to address poverty or other unmet social needs can fill the gaps in broad-based macropolicy, both are subject to a number of execution risks, including lack of accountability, failure to foster innovation, mindless pursuit of “scale” or size in the presence of inefficiency, economic waste via bureaucratic intermediaries, and the absence of impact measurement or evidence of a return on investment. Social entrepreneurship can ameliorate these risks. In its emphasis on human agency and the development of innovative capacity from the bottom up, it complements the large-scale system-changing goals of governments and global philanthropy.

The Role of Multinational Corporations: C. K. Prahalad’s Thesis

In the presence of global capitalism, business has a vital role to play in creating a more sustainable, just, and prosperous world for all people. In practice, the record is mixed. The UN Millennium Development Goals set a target of reducing the number of people living in extreme poverty by half between 1990 and 2015. Thanks in large measure to free trade, by 2015 the number of the world’s seven billion inhabitants subsisting on less than $1.25 a day (the internationally accepted poverty threshold in 1990) had been reduced by half, to 1.1 billion. This definition of poverty, however, is socially constructed, and these subsistence levels of income are associated with fundamental gaps in access to the basic necessities of life—safe water and sanitation, nutrition, quality education, affordable healthcare, transportation, housing, and community safety. To paraphrase Thomas Hobbes, at these subsistence levels, life remains nasty, brutish, and short.

C. K. Prahalad’s “Fortune at the Base of the Pyramid” thesis in 2004 posited an optimistic and hopeful view—one in which multinational companies envisioning the bottom four billion of the world’s population as a market opportunity would become a wellspring of innovation devoted to serving the urgent unmet needs of humanity and eradicating global poverty. This thesis was challenged by Bill Davidow, founder and partner of Mohr, Davidow Ventures, at Santa Clara University’s 2003 Conference “Networked World—Information Technology and Globalization” and later by Ted London in his book The Base of the Pyramid Promise: Building Businesses with Impact and Scale. For Davidow, corporate infrastructure is ill equipped to meet the challenging context and specific needs of the world’s poor. London’s research found that major business contributions beyond case studies and pilots to serve Base of the Pyramid needs have been scant. He posits that big companies have significant advantages in low-cost production and distribution as well as in capital efficiency because of their ability to achieve economies of scale. However, they have significant disadvantages when it comes to close-to-the-ground appreciations of the life circumstances of the poor, their needs, how to coinvent solutions with the poor, and how to overcome the daunting challenges of last-mile distribution in fragmented markets.

The Informal Economy

In the 1980s, a project begun at the University of California Berkeley defined the “informal economy” as the production and distribution of legal goods and services occurring beyond the purview of formal institutions. The project posited that the informal economy resulted from the cost of operating a business within the legal rules of an economy being greater than the costs of operating the same business illegally.14 This project also documented the size of the informal economy in several countries.

Around the same time, Hernando De Soto, using the same definition, documented the informal economy in three market sectors (housing, retail, and transport) in Peru.15 De Soto posited that the informal economy was still inefficient in providing goods and services because of the high costs of being “outside” the system. He argued that, to help the informal economy become both more efficient and part of the formal economy, simple laws governing business formation and operation were necessary.

Twenty years later, Prahalad defined “transaction governance capacity” as the system of rules that regulates and supports business formation.16 Prahalad, like De Soto, felt that the informal economy would continue unless government could ensure that transaction governance costs (the costs of formal rule-based transactions) in the formal economy were less than those costs in the informal economy.

The informal economy dwarfs the formal economy, and it exists as a social institution to fill a void. It is relationship based and has its own norms centered largely on trust and reciprocity. It involves exchange relationships that encompass barter and flexible payment arrangements—arrangements that accommodate the minimal savings and uneven cash flows of the poor.17 Unfortunately, there is no evidence that the informal economy actually reduces the poverty of its participants. Rather, it seems to be an economic system that accommodates poverty.

Theories of the informal economy are relevant to social entrepreneurs because, in many countries, that is where social ventures still operate. In some cases, social ventures may create a sustainable, scalable business in contexts where transaction governance capacity is low by focusing on how to reduce transaction costs (for example, through m-commerce or electronically mediated access to government services). These kinds of efforts can transform previously unstructured and inefficient markets, including those “subsistence economies” with impediments like a lack of infrastructure and the absence of rule of law for ventures that operate in these economies.18

Market Imperfections and Approaches to Poverty Reduction

As we will discuss in chapter 2, Prahalad’s thesis of market-based solutions to poverty as an alternative to top-down government solutions or welfare assumed that markets, as we comprehend them, existed at the base of the economic pyramid. In reality, these markets were large—for essential products and services estimated to be $5 trillion—but extremely fragmented.19 They existed in contexts where the rule of law and the enforceability of contracts were weak, corruption was prevalent, literacy and skill levels were low, and civil engineering deficits were extremely high. In these contexts, market intelligence, awareness of customer needs, and knowledge of the way markets worked were often extremely weak, especially among governmental, philanthropic, and multinational corporations. How barter systems, the absence of fixed pricing, and the conventions of one-to-one sales channels might influence market entry and growth was unknown. Neither were the implications of serving a customer base composed primarily of people working in the informal economy understood. In India, for example, 90 percent of the population is supported by the informal economy with irregular and unpredictable subsistence wages.20

In economics, the term “institutional voids” refers to an absence of the institutional arrangements and actors required to enable the smooth functioning of markets.21 These voids can be reflected in the weak enforcement of formal regulation or contracts, as well as a lack of intermediaries and public infrastructure—factors that raise transaction costs and, as a consequence, significantly hinder market-type activity. From a transaction cost economics perspective, the absence of a fully developed institutional context—including well-defined property rights, rules of exchange, and legal recourse—undermines the emergence of well-functioning capital, labor, and product markets.22 Where such formal institutional arrangements are lacking, they are frequently supplemented by local norms and traditions—both of which are poorly understood by major companies. This makes an understanding of the landscape of potential partners in local operating environments crucial to enterprise success.

Innovation for the Base of the Pyramid requires deep empathy with specific user needs and the constraints of their contexts. The poor are not an undifferentiated mass. For example, in her study of Grameen Shakti’s approach to energy markets in Bangladesh, Nancy Wimmer discovered different design requirements for addressing various BOP income and occupational segments (e.g., farmer, fisherman, merchants, craftsmen, teachers, clinics, schools). While the scale of Shakti’s of-grid lighting solutions for the poor was miniscule in comparison with offerings in developed economies, the unit size and configuration of offerings still varied substantially. At Shakti and elsewhere, distribution modalities also vary substantially depending on BOP income segments.23

BOP markets must be viewed on their own terms, with their own logic. Their characteristics are quite different from the well-articulated markets served by multinational and major companies in advanced economies. In some instances, the latter may be mature markets approaching saturation—a circumstance that Prahalad hypothesized would stimulate interest in serving nascent BOP markets. Still, big companies understand these well-defined markets—and it is here where their cost structures and operating styles fit most comfortably.

Advantages of Bottom-Up Innovation through Social Ventures

Taking a more proximate or bottom-up view involves migrating from a vision of “serving markets” to one of “developing these markets.” This entails a process of co-creation in environments with unique traditions, customs, and ground-level dynamics.24 For the most part, big companies have either ignored or been ineffective in these settings, whereas start-ups are beginning to chart a path to market creation. Their underlying rationales are often quite different from those of classic for-profit firms.25 Frequently, they assume a hybrid orientation, intending to be economically viable while making a societal impact at the same time.26 In this regard, they represent a more humanistic logic than the impersonal forms of market exchange that characterize advanced economies.27

In working with social entrepreneurs from developing countries, we realized that we had more to learn than we had to teach. Their proximate view as bottom-up innovators provides economies of interaction and learning that are inaccessible to big-company strategists and government technocrats—or to us in the hallways of our university setting. These entrepreneurs are in continuous dialogue with those they serve, listening to voices we may never hear. In contexts of extreme resource scarcity, they work with underserved populations to coinvent product and service solutions to some of the most difficult problems in the world. In these settings, markets must be created. Here, bottom-up approaches to social innovation and market creation have advantages in

• adapting the best practices in social marketing and behavioral change to local contexts,

• utilizing existing supply chain infrastructure to complement organizational capabilities,

• tapping local customer financing through regional banks or established microfinance institutions,

• leveraging social capital and local network acumen to access stakeholder resources, and

• combining technology advances with bottom-up innovation requirements on the basis of deep empathy with local needs.

The two examples we use in chapters 4–12, Grameen Shakti and Sankara, illustrate how these advantages work in practice. Shakti leveraged these advantages to become the world’s largest solar home provider. Sankara did so to become the world’s largest provider of affordable eye care. From our work with organizations like Shakti and Sankara, we believe that social entrepreneurs who can integrate their bottom-up perspectives with the knowledge of seasoned entrepreneurs about how to grow a business hold great promise for successful ventures that serve the poor.

Building a successful venture to serve marginalized populations in settings with low trust in government and outsiders requires a deep appreciation of the local customs, sociopolitical structures, and norms that form the basis for local systems of economic exchange. The bottom-up and participatory approach to enterprise development and market creation in this guide for social entrepreneurs contrasts with top-down methods that have dominated government policy and the BOP market entry strategies of multinational companies. It integrates social innovation with design for affordability as critical factors in serving the poor.28 It is consistent with research by Jain and Koch that underscores the importance of embedding solutions in local ecosystems.29 In their in-depth case analysis of of-grid BOP enterprises they conclude that viable solutions ultimately “involve mixing and matching state of the art technologies with indigenous knowledge, as well as an appreciation of resident absorptive capacity,” a process they call “indigenization.” They suggest that it is possible to address both economic viability and affordability constraints “through the development of micro-provisioning mechanisms that involve understanding unit economics across improvised value chains.” And finally, they highlight the importance of having incentive plans and logistics “for last mile agent-based sales and service” when “co-producing and embedding solutions” in BOP environments. With these kinds of arrangements at the ecosystem level, “organizations can increase capital efficiency, align solutions with the informal rules of exchange, and tap into extant trust-based social structures, thereby securing legitimacy for their endeavors.”

Social entrepreneurs are leading the way in discovering how to serve these distinct markets:

• They have superior knowledge of customer needs and practical knowledge of how to create compelling value equations through cost reduction or enhancing customer value.

• They possess knowledge about how culture, language, symbols, and opinion leaders shape attitudes. This knowledge enhances their ability to make effective use of local media (e.g., through imaginative soap operas for educating customers or mobile platform applications in the local language).

• They understand local distribution and how existing channels might be appropriated to reach customers.

• They understand local stakeholders and, as we address in chapter 5, how they might be enlisted to mitigate risks or leveraged through value chain innovation.

Unlike multinational companies that enter Base of the Pyramid markets from the outside, social entrepreneurs build enterprises and markets from an inside or bottom-up perspective. In settings where word of mouth is critical, they understand the bases of trust and how specific elements of brand identity influence early adoption and wider market penetration.

To Recap

In this chapter we examined top-down and bottom-up approaches to serving unmet human needs. In the context of market-based solutions, we revisited the “eradicating poverty through profits” thesis of the late C. K. Prahalad and the BOP innovation leadership role he envisioned for major companies. While there is growing evidence of innovation, social entrepreneurs, rather than major companies, are leading. Their proximate view of these unserved markets holds particular promise for producing transformative change in Base of the Pyramid communities.

The growth of social entrepreneurship as a field coincides with the emergence of a “fourth sector” that bridges the rationalities of public, private, and nonprofit or philanthropic organizations. At the nexus of this convergence, social entrepreneurship is unleashing creativity and becoming a potential wellspring of ideas for disruptive innovation. In contrast to charity, big companies that are driven by short-term profits and often viewed as extractive—or distrusted governments widely viewed as offering bureaucratic solutions gamed by incumbent actors for private gain—social entrepreneurs are rooted in local contexts and perceived as empowering local communities. They are a vital source of research and development because they are on the ground, addressing the challenges of market creation in the specific context of resource constraints and market imperfections.

Pamela Hartigan’s 2012 speech at the Skoll World Forum described as outrage the response of “ordinary citizens against an increasingly unfair and unsustainable society.” This outrage was reflected in a July 26, 2013, editorial by Peter Bufett:30

It’s time for a new operating system. Not a 2.0 or a 3.0, but something built from the ground up—a new code. What we have is a crisis of imagination. Albert Einstein said that you cannot solve a problem with the same mind-set that created it. Foundation dollars should be the best “risk capital” out there. There are people working hard at showing examples of other ways to live in a functioning society that truly creates greater prosperity for all (and I don’t mean more people getting to have more stuff ).

Money should be spent trying out concepts that shatter current structures and systems that have turned much of the world into one vast market. Is progress really Wi-Fi on every street corner? No. It’s when no 13-year-old girl on the planet gets sold for sex. But as long as most folks are patting themselves on the back for charitable acts, we’ve got a perpetual poverty machine. It’s an old story; we really need a new one.

As many will recall from childhood memories of Humpty Dumpty, all the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again. The top-down, macroeconomy approaches of governments to eradicate poverty reflect the orthodoxies of political majorities that float above the realities of impoverished communities. As with the outside-in efforts of major companies to develop market-based solutions to poverty, they often suffer from a lack of connectedness with the lives of real people. This empathy deficit undermines an appreciation of market failure and deep thinking about the factors that hold unjust equilibriums in place. In this context, macromeasures of economic well-being like GDP per capita mask the realities of inequality, widespread poverty, and the systemic barriers to social progress. In this chapter we tried to show why existing approaches (governmental, philanthropic, and corporate) have fallen short. In the next chapter, we take a closer look at the market at the Base of the Pyramid.

Background Resources

Ansari, Shahzad, Kamal Munir, and Tricia Gregg. “Impact at the ‘Bottom of the Pyramid’: The Role of Social Capital in Capability Development and Community Empowerment.” Journal of Management Studies 49, no. 4 (2012): 813–842.

Battilana, Julie, and Matthew Lee. “Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing—Insights from the Study of Social Enterprises.” Academy of Management Annals 8 (2014): 397–441.

Bugg-Llevine, Antony, and Jed Emerson. Impact Investing: Transforming How We Make Money While Making a Difference. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2011.

Coase, R. H. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (October 1960): 1–44.

Desa, Geoffrey, and James Koch. “Building Sustainable Social Ventures at the Base of the Pyramid.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8 (2014): 146–174.

De Soto, Hernando. The Other Path. New York: Harper and Row, 1989.

The Economist. “Poverty Elucidation Day.” October 20, 2014.

Forbes. “America Has Less Poverty Than Sweden.” September 10, 2012.

Grimes, Matthew G., Jeffery S. McMullen, Timothy J. Vogus, and Toyah L. Miller. “Studying the Origins of Social Entrepreneurship.” Academy of Management Review 38, no. 3 (July 1, 2013): 460–463.

Hammond, A., W. Kramer, J. Tran, R. Katz, and W. Courtland. The Next 4 Billion: Market Size and Business Strategy at the Base of the Pyramid. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2007.

Jain, S., and J. Koch. “Articulated Embedding in the Development of Markets for Under-Served Communities: The Case of Clean-Energy Provision to Of-Grid Publics.” Academy of Management Annual Conference, Vancouver, BC, August 2015.

Jain, S., and J. Koch. “Conceptualizing Markets for Underserved Communities.” In Sustain-ability, Society, Business Ethics, and Entrepreneurship, edited by A. Guerber and G. Mark-man, 71–91. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2016.

Khanna, Tarun, and Krishna G. Palepu. “Why Focused Strategies May Be Wrong for Emerging Markets.” Harvard Business Review, July-August 1997.

London, Ted. The Base of the Pyramid Promise—Building Businesses with Impact and Scale. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Piketty, Thomas. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

Portes, Alejandro, Manuel Castells, and Lauren A. Benton, eds. The Informal Economy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Prahalad, C. K. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits. Philadelphia: Wharton School Publishing, 2010.

Social Progress Index. “2017 Social Progress Index.” Accessed March 14, 2018. https://www.socialprogressindex.com/.

Sowell, Thomas. Trickle Down Theory. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2012.

Sridharan, S., and M. Viswanathan. “Marketing in Subsistence Marketplaces: Consumption and Entrepreneurship in a South Indian Context.” Journal of Consumer Marketing 25, no. 7 (2008): 455–462.

Viswanathan, Madhu. Bottom-Up Enterprise: Insights from Subsistence Marketplaces. eBook-partnership: eText and Stripes Publishing, 2016.

Williamson, Oliver E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985.

Wimmer, Nancy. Green Energy for a Billion Poor. Vatterstetten: MCRE Verlag, 2012.