Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Business Ethics, Seventh Edition 7th Edition

A Stakeholder and Issues Management Approach

Joseph Weiss (Author)

Publication date: 11/23/2021

Joseph Weiss's Business Ethics is a pragmatic, hands-on guide for determining right and wrong in the business world. To be socially responsible and ethical, Weiss maintains, businesses must acknowledge the impact their decisions can have on the world beyond their walls. An advantage of the book is the integration of a stakeholder perspective with an issues and crisis management approach so students can look at how a business's actions affect not just share price and profit but the well-being of employees, customers, suppliers, the local community, the larger society, other nations, and the environment.

Weiss includes twenty-three cases that immerse students directly in contemporary ethical dilemmas. Eight new cases in this edition include Facebook's (mis)use of customer data, the impact of COVID-19 on higher education, the opioid epidemic, the rise of Uber, the rapid growth of AI, safety concerns over the Boeing 737, the Wells Fargo false saving accounts scandal, and plastics being dumped into the ocean.

Several chapters feature a unique point/counterpoint exercise that challenges students to argue both sides of a heated ethical issue. This edition has eleven new point/counterpoint exercises, addressing questions like, Should tech giants be broken apart? What is the line between free speech and dangerous disinformation? Has the Me Too movement gone too far? As with previous editions, the seventh edition features a complete set of ancillary materials for instructors: teaching guides, test banks, and PowerPoint presentations.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Joseph Weiss's Business Ethics is a pragmatic, hands-on guide for determining right and wrong in the business world. To be socially responsible and ethical, Weiss maintains, businesses must acknowledge the impact their decisions can have on the world beyond their walls. An advantage of the book is the integration of a stakeholder perspective with an issues and crisis management approach so students can look at how a business's actions affect not just share price and profit but the well-being of employees, customers, suppliers, the local community, the larger society, other nations, and the environment.

Weiss includes twenty-three cases that immerse students directly in contemporary ethical dilemmas. Eight new cases in this edition include Facebook's (mis)use of customer data, the impact of COVID-19 on higher education, the opioid epidemic, the rise of Uber, the rapid growth of AI, safety concerns over the Boeing 737, the Wells Fargo false saving accounts scandal, and plastics being dumped into the ocean.

Several chapters feature a unique point/counterpoint exercise that challenges students to argue both sides of a heated ethical issue. This edition has eleven new point/counterpoint exercises, addressing questions like, Should tech giants be broken apart? What is the line between free speech and dangerous disinformation? Has the Me Too movement gone too far? As with previous editions, the seventh edition features a complete set of ancillary materials for instructors: teaching guides, test banks, and PowerPoint presentations.

Joseph W. Weiss, PhD, is Professor of Management and Senior Fellow with the Center of Business Ethics at Bentley University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He specializes in Executive Leadership Development, Business Ethics, and Management & Technology. He served as a Senior Fulbright Program Specialist in Moscow and Madrid and was a business program evaluator with the Fulbright program for two years. He has taught and lectured in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. He is author of several books and articles in the fields of business ethics, project management, leadership, organizational change, and technology management. He has won awards in his university teaching, and was Chair of the Consulting Division in the national Academy of Management. He consults to companies in organizational change, leadership development, and business ethics.

Business Ethics, the Changing Environment, and Stakeholder Management

1.1 Business Ethics and the Changing Environment

1.2 What Is Business Ethics? Why Does It Matter?

1.3 Levels of Business Ethics

1.4 Five Myths about Business Ethics

1.5 Why Use Ethical Reasoning in Business?

1.6 Can Business Ethics Be Taught?

1.7 Plan of the Book

Chapter 2

Ethical Principles, Quick Tests, and Decision-Making Guidelines

2.1 Ethical Reasoning and Moral Decision Making

2.2 Ethical Principles and Decision Making

2.3 Four Social Responsibility Roles

2.4 Levels of Ethical Reasoning and Moral Decision Making

2.5 Identifying and Addressing Ethical Dilemmas

2.6 Individual Ethical Decision-Making Styles

2.7 Quick Ethical Tests

2.8 Concluding Comments

Chapter 3

Stakeholder and Issues Management Approaches

3.1 Stakeholder Theory and the Stakeholder Management Approach Defined

3.2 Why Use a Stakeholder Management Approach for Business Ethics?

3.3 How to Execute a Stakeholder Analysis

3.4 Negotiation Methods: Resolving Stakeholder Disputes

3.5 Stakeholder Management Approach: Using Ethical Principles and Reasoning

3.6 Moral Responsibilities of Cross-Functional Area Professionals

3.7 Issues Management: Integrating a Stakeholder Framework

3.8 Managing Crises

Chapter 4

The Corporation and External Stakeholders: Corporate Governance: From the Boardroom to the Marketplace

4.1 Managing Corporate Social Responsibility in the Marketplace

4.2 Managing Corporate Responsibility with External Stakeholders

4.3 Managing and Balancing Corporate Governance, Compliance, and Regulation

4.4 The Role of Law and Regulatory Agencies and Corporate Compliance

4.5 Managing External Issues and Crises: Lessons from the Past (Back to the Future?)

Chapter 5

Corporate Responsibilities, Consumer Stakeholders, and the Environment

5.1 Corporate Responsibility toward Consumer Stakeholders

5.2 Corporate Responsibility in Advertising

5.3 Controversial Issues in Advertising: The Internet, Children,

5.4 Managing Product Safety and Liability Responsibly

5.5 Corporate Responsibility and the Environment

Chapter 6

The Corporation and Internal Stakeholders: Values-Based Moral Leadership, Culture, Strategy, and Self-Regulation

6.1 Leadership and Stakeholder Management

6.2 Organizational Culture, Compliance, and Stakeholder Management

6.3 Leading and Managing Strategy and Structure

6.4 Leading Internal Stakeholder Values in the Organization

6.5 Corporate Self-Regulation and Ethics Programs: Challenges and Issues

Chapter 7

Employee Stakeholders and the Corporation

7.1 Employee Stakeholders in the Changing Workforce

7.2 The Changing Social Contract between Corporations and Employees

7.3 Employee and Employer Rights and Responsibilities

7.4 Discrimination, Equal Employment Opportunity, and Affirmative Action Discrimination

Workplace

7.6 Whistle-Blowing versus Organizational Loyalty

Chapter 8

Business Ethics and Stakeholder Management in the Global Environment

8.1 The Connected Global Economy and Globalization

8.2 Managing and Working in a Different Global World: Professional and Ethical Competencies

8.3 Societal Issues and Globalization: The Dark Side

8.4 Multinational Enterprises as Stakeholders

8.5 Triple Bottom Line, Social Entrepreneurship, and Microfinancing

8.6 MNEs: Stakeholder Values, Guidelines, and Codes for

8.7 Cross-Cultural Ethical Decision Making and Negotiation Methods

1

BUSINESS ETHICS, THE CHANGING ENVIRONMENT, AND STAKEHOLDER MANAGEMENT

1.1 Business Ethics and the Changing Environment

1.2 What Is Business Ethics? Why Does It Matter?

1.4 Five Myths about Business Ethics

1.5 Why Use Ethical Reasoning in Business?

1.6 Can Business Ethics Be Taught?

1. Education Pushed to the Brink: How Covid-19 Is Redefining Recruitment and Admissions Decisions

2. Classic Ponzi Scheme: Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC: Wall Street Trading Firm

3. Cyberbullying: Who’s to Blame and What Can Be Done?

OPENING CASE

Blogger: “Hi. i download music and movies, limewire, torrent [and other sites]. Is it illegal for me to download or is it just illegal for the person uploading it. Does anyone know someone who was caught and got into trouble for it, what happened to them. Personally I don’t see a difference between downloading a song or taping it on a cassette from a radio!”1

The Covid-19 crisis has accelerated the use of online technologies, particularly social media, mobile phone apps, entertainment, and communication sites. Illegal file sharing continues to be problematic. “The U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Global Innovation Policy Center estimated in 2019 that online piracy accounts for 26.6 billion views of U.S.-produced movies and 126.7 billion views of U.S.-produced TV episodes every year. The economic impact of digital video piracy extends far beyond the movie and television industries; in total, it is responsible for at least $29.2 billion in lost domestic revenues, 230,000 in lost American jobs, and $47.5 billion in reduced GDP [gross domestic product].”2 The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), on behalf of its member companies and copyright owners, has sued more than 20,000 people and settled 2,500 cases for unlawful downloading. RIAA detectives log on to peer-to-peer networks where they easily identify illegal activity since users’ shared folders are visible to all. The majority of these cases have been settled out of court for $1,000 to $3,000, but fines per music track can go up to $150,000 under the Copyright Act.

More recently, a practice known as “torrenting” has contributed to illegal file sharing, particularly with books, movies, and games. A “torrent” or “tracker” breaks up “the big file and chops it up into little pieces, called ‘packets’… that are shared throughout a network of computers also downloading the same file you are.” You are usually downloading it from a network of peers. Copyrighted files are illegal to download without paying, and some of these technologies make downloading easier. The risks for becoming part of a “torrent community” or downloading copyrighted files for “free” can be substantial. Trolls, hackers, and other vipers can track, steal, and corrupt your computer system. “Anti-piracy activists claim that copyright infringement (most of it done through torrenting) is costing the U.S. economy $250 billion per year.”3

The nation’s first file-sharing defendant to challenge an RIAA lawsuit, Jammie Thomas-Rasset, reached the end of the appeals process to overturn a jury-determined $222,000 fine in 2013. She was ordered to pay this amount, which she argued was unconstitutionally excessive, for downloading and sharing 24 copyrighted songs using the now-defunct file-sharing service Kazaa. The Supreme Court has not yet heard a file-sharing case, having also declined without comment to review the only other appeal following Thomas-Rasset’s case. (In that case, the court let stand a federal jury–imposed fine of $675,000 against Joel Tenenbaum for downloading and sharing 30 songs.) “As I’ve said from the beginning, I do not have now, nor do I anticipate in the future, having $220,000 to pay this,” Thomas-Rasset said. “If they do decide to try and collect, I will file for bankruptcy as I have no other option.”4

Once the well-funded RIAA initiates a lawsuit, many defendants are pressured to settle out of court in order to avoid oppressive legal expenses. Others simply can’t take the risk of large fines that juries have shown themselves willing to impose.

New technologies and the trend toward digital consumption, as noted above, have made intellectual property both more critical to businesses’ bottom lines and more difficult to protect. No company, big or small, is immune to the intellectual property protection challenge. Illegal downloads of music are not the only concern. In 2011, the U.S. Copyright Group initiated what it called “the largest illegal downloading case in U.S. history” at the time, suing over 23,000 file sharers who illegally downloaded Sylvester Stallone’s movie The Expendables. This case was expanded to include the 25,000 users who also downloaded Voltage Pictures’ The Hurt Locker, which increased the total number of defendants to approximately 50,000, all of whom used peer-to-peer downloading through BitTorrent. The lawsuits were filed based on the illegal downloads made from an Internet Protocol (IP) address. The use of an IP address as identifier presents ethical issues—for example, should a parent be responsible for a child downloading a movie through the family’s IP address? What about a landlord who supplied Internet to a tenant?

Digital books are also now in play. In 2012, a now-classic lawsuit was filed in China against technology giant Apple for sales of illegal book downloads through its App Store. Nine Chinese authors are demanding payment of $1.88 million for unauthorized versions of their books that were submitted to the App Store and sold to consumers for a profit. Again, the individual IP addresses are the primary way of determining who performed the illegal download. Telecom providers and their customers face privacy concerns, as companies are being asked for the names of customers associated with IP addresses identified with certain downloads.

Privacy activists argue that an IP address (which identifies the subscriber but not the person operating the computer) is private, protected information that can be shown during criminal but not civil investigations. Fred von Lohmann, a senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, has suggested on his organization’s blog that “courts are not prepared to simply award default judgments worth tens of thousands of dollars against individuals based on a piece of paper backed by no evidence.”5

1.1 Business Ethics and the Changing Environment

The Internet, Zoom, and other apps—with enhanced use during Covid-19—are now among the primary ways of communicating, doing business, and managing life—individually, organizationally, nationally, and internationally. Those less fortunate in the United States as well as the last “third billion” of people in undeveloped countries who are not and cannot afford broadband access are particularly disadvantaged.6 Covid-19 has been a wake-up call to the health and welfare and technological needs of the United States and businesses worldwide. Also, as this chapter’s opening case shows, there is more than one side to every complex issue and debate involving businesses, consumers, families, other institutions, and professionals. When stakeholders, governments, and companies cannot agree or negotiate competing claims among themselves, the issues generally go to the courts, as was shown in the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

Stakeholders are individuals, companies, groups, and even governments and their subsystems that cause and respond to external issues, opportunities, and threats. Global crises, natural disasters, corporate scandals, globalization, deregulation, mergers, technology, and global cyberterrorism have accelerated the rate of change and brought about a climate of uncertainty in which stakeholders must make business and moral decisions. Issues concerning questionable ethical and illegal business practices confront everyone, as exemplified in some of the following examples:

• Covid-19 and events surrounding and heightened by it have ushered in a host of contemporary issues that have both legal and ethical urgency. Cybersecurity is a necessity for all. Hackers demanding and getting ransomware extracted $144 million in 2020 from municipality governments, universities, and private businesses.7

• Public outrage over institutional racism, triggered by the May 2020 murder of George Floyd, gave rise to the Black Lives Matter movement nationally and internationally and has pressured police and other criminal justice institutions to reimagine their organizations and practices.

• While Covid-19 has in many ways overshadowed other previous crises, the subprime-lending crisis of 2008 is also memorable, as it affected stakeholders as varied as consumers, banks, mortgage companies, real estate firms, and homeowners. Many companies that sold mortgages to unqualified buyers lied about low-risk, high-return products. Wall Street companies, while thriving, are also settling lawsuits stemming from the 2008 crisis. Hundreds of thousands of subprime borrowers struggled from that crisis, and many lost their homes. Subprime securities still pose a significant legal risk to the firms that packaged them, using capital that could be gainfully applied to the current economy.”8 Standing now as a landmark financial crisis, in 2011, Bank of America announced that it would “take a whopping $20 billion hit to put the fallout from the subprime bust behind it and satisfy claims from angry investors.”9 The ethics and decisions precipitating the crisis contributed to tilt the U.S. economy toward recession, with long-lasting effects.

• The corporate scandals in the 1990s through 2001 at Enron, Adelphia, Halliburton, MCI WorldCom, Tyco, Arthur Andersen, Global Crossing, Dynegy, Qwest, and Merrill Lynch are now deemed “classic cases” economically and in business ethics; and similar scandals could reoccur at other firms without responsible diligence, especially with democracies across the globe threatened by domestic terrorism, lax citizen and environmental protection policies, and shared governance by stakeholders and stockholders. We reference these classic cases since they jolted shareholder and public confidence in Wall Street and corporate governance. Enron’s bankruptcy with assets of $63.4 billion defies imagination, and WorldCom’s bankruptcy set the record for the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history.10 Only 22 percent of Americans express a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in big business, compared to 65 percent who express confidence in small business.11 Confidence in big business reached its highest point in 1974 at 34 percent, and even during the dot-com boom in the late 1990s it hovered at 30 percent. The lowest rating of 16 percent was polled in 2009 after the subprime-lending crisis, and although public confidence has since increased slightly, the significant differential in American confidence between big and small business belies a public mistrust of big business that may not be easily repaired.12

• According to the New York Times, “Even as millions of people have lost their jobs during the [Covid-19] pandemic, the soaring stock market since the spring of 2020 has delivered outsized gains to the wealthiest Americans. And few among the superrich have done as well as corporate executives who received stock awards this year.”13 Moreover, the debate continues over excessive pay to those chief executive officers (CEOs) who continue to post poor corporate performance. Large bonuses paid out during the financial crisis made executive pay a controversial topic, yet investors did little to solve the issue. “Investors had the opportunity to provide advisory votes on executive pay at financial firms that received TARP [Troubled Asset Relief Program] funds in 2009, and they gave thumbs up to pay packages at every single one of those institutions. This proxy season, with advisory votes now widely available (thanks to the Dodd-Frank Act), only five companies’ executive compensation packages have received a thumbs down from shareholders.”14 “Realized CEO compensation grew 105.1% from 2009 to 2019, the period capturing the recovery from the Great Recession; in that period granted CEO compensation grew 35.7%. In contrast, typical workers in these large firms saw their average annual compensation grow by just 7.6% over the last 10 years.”15 A recent analysis showed that in 2020, the average multiple of CEO compensation to that of rank-and-file workers is 320.”16

• During the Covid-19 pandemic, some critics on the right of the political spectrum continue to argue that companies still can become overregulated. Others argue that more sufficient and effective regulation of the largest financial and social media companies is needed to overcome the inequalities in income, pay, wealth, and taxes that have been created. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 was one response to the scandals in the early 2000s. This act states that corporate officers will serve prison time and pay large fines if they are found guilty of fraudulent financial reporting and of deceiving shareholders. Implementing this legislation requires companies to create accounting oversight boards, establish ethics codes, show financial reports in greater detail to investors, and have the CEO and chief financial officer (CFO) personally sign off on and take responsibility for all financial statements and internal controls. Implementing these provisions is costly for corporations. Some claim their profits and global competitiveness are negatively affected and the regulations are “unenforceable.”17 More recently, Covid-19 and the ensuing economic crisis has exposed an increasing racial divide along with income inequalities between those at the top of the income and wealth spectrum and the shrinking middle- and lower-income levels.

• U.S. firms before Covid were outsourcing work to other countries to cut costs and improve profits, work that some argue could be accomplished in the United States. Estimates of U.S. jobs outsourced range from 104,000 in 2000 to 400,000 in 2004, and on average, 300,000 annually. “Forrester Research estimated that 3.3 million U.S. jobs and about $136 billion in wages would be moved to overseas countries such as India, China, and Russia by 2015. Deloitte Consulting reported that 2 million jobs would move from the United States and Europe to overseas destinations within the financial services business. Across all industries the emigration of service jobs can be as high as 4 million.”18 Do U.S. employees who are laid off and displaced need protection, or is this practice part of another societal business transformation? Is the United States becoming part of a global supply chain in which outsourcing is “business as usual,” or is the working middle class in the United States and elsewhere at risk of predatory industrial practices and ineffective government polices?19 Still, there are critics in 2020 who argue that outsourcing does lower company costs, increases profits for stockholders, and gives lower prices to consumers—resulting in higher standards of living and an overall increase in employment for larger numbers of the population.

• Will robots, robotics, and artificial intelligence (AI) applications replace humans in the workplace? This interesting but disruptive development poses concerns. “The outsourcing of human jobs as a side effect of globalization has arguably contributed to the current unemployment crisis. However, one rather extreme trend sees humans done away with altogether, even in the low-wage countries where many American jobs have landed.”20 What will be the ethical implications of the next wave of AI development, “where full-blown autonomous self-learning systems take us into the realm of science fiction—delivery systems and self-driving vehicles alone could change day-to-day life as we know it, not to mention the social implications.”21 AI also extends into electronic warfare (drones), education (robot assisted or led), and manufacturing (a Taiwanese company replaced a “human force of 1.2 million people with 1 million robots to make laptops, mobile devices, and other electronics hardware for Apple, Hewlett-Packard, Dell, and Sony”).22 One futurist predicted that as many as 50 million jobs could be lost to machines by 2030, and even 50 percent of all human jobs by 2040. These, again, may be extreme views.

These large macro-level issues taken together underlie many ethical dilemmas that affect business and individual decisions among stakeholders in organizations, professions, as well as individual lives. Before discussing stakeholder theory, the management approach that it is based on, and how these perspectives and methods can help individuals and companies better understand how to make more socially responsible decisions, we take a brief look at the broader environmental forces that affect industries, organizations, and individuals.

Seeing the “Big Picture”

Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Thomas Friedman continues to track mega changes, including those resulting from Covid, on a global scale. His 2011 book, That Used to Be Us: How America Fell Behind in the World It Invented and How We Can Come Back, is particularly prophetic now. In it, he suggests an agenda for change to meet larger challenges. His book The Lexus and the Olive Tree vividly illustrates a macroenvironmental perspective that provides helpful insights into stakeholder and issues management mind-sets and approaches.23 Friedman notes:

Like everyone else trying to adjust to this new globalization system and bring it into focus, I had to retrain myself and develop new lenses to see it. Today, more than ever, the traditional boundaries between politics, culture, technology, finance, national security, and ecology are disappearing. You often cannot explain one without referring to the others, and you cannot explain the whole without reference to them all. I wish I could say I understood all this when I began my career, but I didn’t. I came to this approach entirely by accident, as successive changes in my career kept forcing me to add one more lens on top of another, just to survive.24

After quoting Murray Gell-Mann, the Nobel laureate and former professor of theoretical physics at Caltech, Friedman continues:

We need a corpus of people who consider that it is important to take a serious and professional look at the whole system. It has to be a crude look, because you will never master every part or every interconnection. Unfortunately, in a great many places in our society, including academia and most bureaucracies, prestige accrues principally to those who study carefully some [narrow] aspect of a problem, a trade, a technology, or a culture, while discussion of the big picture is relegated to cocktail party conversation. That is crazy. We have to learn not only to have specialists but also people whose specialty is to spot the strong interactions and entanglements of the different dimensions, and then take a crude look at the whole.25

POINT/COUNTERPOINT

File Sharing: Still a Problem, but Harmful Theft or Sign of the Times?

Instructions: Each student in this exercise must select either Point or CounterPoint arguments (no in-between choices), defend that choice, and state why you believe either one or the other. Be ready to argue your choice as the instructor directs. Afterward, the class is debriefed, and there is further discussion as a class.

POINT: File sharing is theft, illegal, and endangers the entire structure of incentives that allows the creation of digital media. Downloading even one copyrighted song, movie, book, or game illegally has severe costs for the musicians and the owners and employees of the companies that produce songs, and for legitimate online music services, not to mention consumers who purchase music legally. Those responsible, even peripherally, for illegal file sharing should be tracked down by any means possible and held accountable for these costs and damages.

COUNTERPOINT: The generation that grew up with the advent of digital media has a well-cultivated expectation of ease and freedom when it comes to accessing music, television, and books using the Internet. Not only younger individuals but consumers worldwide are prone through torrenting and other enticing sites to download “free” materials and are at risk, because their files and devices can also be hacked. Companies are willing to capitalize on that ease to boost their profits. It is unethical to use technology and the legal system to “make examples” of those (possibly innocent bystanders whose IP addresses were used by others) who are simply showing the flaws and gaps in distribution strategies.

“I watch some of my favorite shows on Hulu.com for free and I buy others on Amazon or iTunes. I pay a fee to use Pandora for ad-free Internet radio, or Spotify for specific music playlists. But like many of my friends, I don’t own a TV, so when there is no other way to access a show, I will download it from a torrent [file-sharing] site since I can, and my friends do as well.”

—Interview with a Generation Y “Millennial”

“The Boston Celtics are my favorite basketball team, but unfortunately, I live in the New York area. This means that the local sports channel only shows New York Knicks games and Brooklyn Nets games. With no other way of watching every Celtics game, I am enticed to go on Reddit and watch the Celtics game streamed illegally. Is this my fault? It’s available and my friends do it.”

—Interview with a Generation Y “Millennial”

Environmental Forces and Stakeholders

Organizations and individuals are embedded in and interact with multiple changing local, national, and international environments, as contemporary media and news and the above discussions illustrate. Each chapter of this book provides some context for reported events, controversies, and ethical arguments. Chapter 8 in particular illustrates and references an international perspective, as do sections throughout this text. These environments are increasingly moving into a global system of dynamically interrelated interactions among businesses and economies, even though some scholars and pundits argue that globalization has been in retreat in part because of the pandemic and also because of emergent nationalistic, autocratic leaders who claim democracies are failing.26

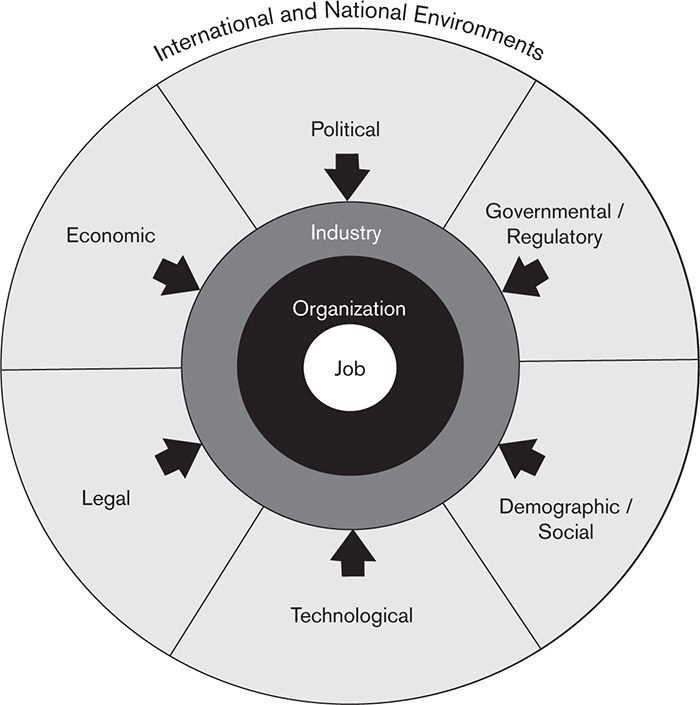

Still, the motto “Think globally before acting locally” is relevant in many situations. The macro-level environmental forces shown in Figure 1.1 affect the performance and operation of industries, organizations, and jobs. This framework can be used as a starting point to identify trends, issues, opportunities, and ethical problems that affect people and stakes in different levels. A first step toward understanding stakeholder issues is to gain an understanding of environmental forces that influence stakeholders, their issues, and stakes. As we present an overview of these environmental forces here, think of the effects and pressures each of the forces has on you.

Figure 1.1

Environmental Dimensions Affecting Industries, Organizations, and Jobs

The economic environment is under Covid-19 stress presently but shows potential for rebounding once vaccinations and containment start to work. The global economy, suppressed from 2016 to 2021, will rebound and continue to evolve through renewed global trade, markets, and resource flows, despite previous debates and forced ideologies to the contrary. The rise of China has overshadowed India presently. The United States will have to regain its international presence and credibility post-Covid with new trade opportunities and business practices.

The technological environment has become a necessity, no longer a luxury. Although speed, scope, economy of scale, and efficiency are transforming transactions through information technology, privacy and surveillance issues continue to emerge. The boundary between surveillance and convenience also continues to blur. Has the company or organization for which you work used surveillance to monitor Internet use?

Disinformation and misinformation have plagued and still threaten the United States and some other countries and democracies. International and national “bad actors,” domestic terrorist groups, and divides between “red” and “blue” political and ideological mind-sets will have to be mended for real change to occur.

The government and legal environments are also in a state of repair after the brutal January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, with continuing identity and dangerous divisive politics in the U.S. Congress. But regulatory laws such as the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 that established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, whose mission is to protect consumers by carrying out federal consumer financial laws, educating consumers, and hearing complaints from the public, will help citizens with credit card abuses in particular.27

The demographic and social environment continues to change as national boundaries experience the effects of globalization and the workforce becomes more diverse. The Black Lives Matter movement has reinvigorated interest in solving institutional racism. Emphasis currently is on addressing concrete national, state, and local (in the United States) policy changes with regard to income inequality, justice of the treatment of Black and minority citizens by law enforcement officers, and inclusiveness policies and practices in and across institutions. Employers and employees are faced with Covid-19 problems of shutdowns, stress, loss, and employment as well as employability. At the same time, employers and employees continue to face tensions with demographic factors related to aging and very young populations; minorities becoming majorities; generational differences; and the effects of downsizing and outsourcing on morale, productivity, and security. Those companies that survive the Covid-19 crisis face economic survival issues, but they also must strive to effectively integrate a workforce that is at once increasingly younger and older, less educated and more educated, technologically sophisticated and technologically unskilled.

In this book these environmental factors are incorporated into a stakeholder and issues management approach that also includes an ethical analysis of actors external and internal to organizations. The larger perspective underlying these analytical approaches is represented by the following question: How can the common good of all stakeholders in controversial situations be realized?

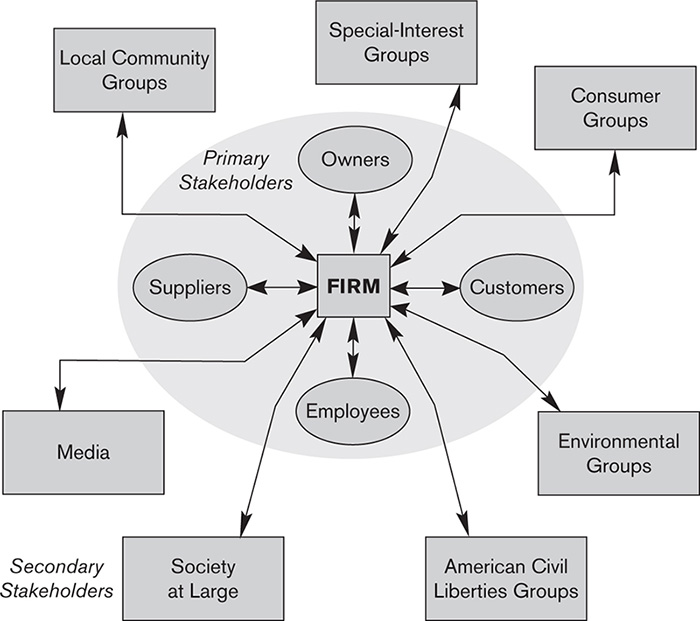

Stakeholder Management Approach

How do companies, the media, political groups, consumers, employees, competitors, and other groups respond in socially ethical and responsible ways when impacted by an issue, dilemma, threat, or opportunity from the environments just described? The stakeholder theory expands a narrow view of corporations from a stockholder-only perspective to include the many stakeholders who are also involved in how corporations envision the future, treat people and the environment, and serve the common good for the many. Implementing this view starts with the ethical imperatives and moral understandings that corporations that use natural resources and the environment must serve, as well as providing for those who buy their products and services. This view and accompanying methods are explained in more detail in Chapters 2 and 3 especially and inform the whole text.

The stakeholder theory begins to address these questions by enabling individuals and groups to articulate collaborative, win-win strategies based on:

1. Identifying and prioritizing issues, threats, or opportunities

2. Mapping who the stakeholders are

3. Identifying their stakes, interests, and power sources

4. Showing who the members of coalitions are or may become

5. Showing what each stakeholder’s ethics are (and should be)

6. Developing collaborative strategies and dialogue from a “higher ground” perspective to move plans and interactions to the desired closure for all parties

Chapter 3 lays out specific steps and strategies for analyzing stakeholders. Our aim is to develop awareness of the ethical and social responsibilities of different stakeholders. As Figure 1.2 illustrates, there can be a wide range of stakeholders in any situation. We turn to a general discussion of “business ethics” in the following section to introduce the subject and motivate you to investigate ethical dimensions of organizational and professional behavior.

Figure 1.2

Primary versus Secondary Stakeholder Groups

1.2 What Is Business Ethics? Why Does It Matter?

Business ethicists ask, “What is right and wrong, good and bad, harmful and beneficial regarding decisions and actions in organizational transactions?” Ethical reasoning and logic is explained in more detail in Chapter 2, but we note here that approaching problems using a moral frame of reference can influence solution paths as well as options and outcomes. Since “solutions” to business and organizational problems may have more than one alternative, and sometimes no right solution may seem available, using principled, ethical thinking provides structured and systematic ways of making decisions based on values, as opposed to relying on perceptions that may be distorted, pressures from others, or the quickest and easiest available options that may prove more harmful.

What Is Ethics, and What Are the Areas of Ethical Theory?

Ethics derives from the Greek word ethos—meaning “character”—and is also known as moral philosophy, which is a branch of philosophy that involves “systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct.”28 Ethics involves understanding the differences between right and wrong thinking and actions and using principled decision making to choose actions that do not hurt others. Although intuition and creativity are often involved in having to decide between what seems like two “wrong” or less desirable choices in a dilemma where there are no easy alternatives, using ethical principles to inform our thinking before acting hastily may reduce the negative consequences of our actions. Classic ethical principles are presented in more detail in Chapter 2, but by way of an introduction, three general areas constitute a framework for understanding ethical theories: metaethics, normative ethics, and descriptive ethics.29

Metaethics considers where one’s ethical principles “come from, and what they mean.” Do one’s ethical beliefs come from what society has prescribed? Did our parents, family, or religious institutions influence and shape our ethical beliefs? Are our principles part of our emotions and attitudes? Metaethical perspectives address these questions and focus on issues of universal truths, the will of God, the role of reason in ethical judgments, and the meaning of ethical terms themselves.30 More practically, if we are studying a case or observing an event in the news, we can inquire about what and where a particular CEO’s or professional’s ethical principles (or lack thereof ) are and where in that person’s life and work history these beliefs were adopted.

Normative ethics is more practical. It involves prescribing ethical behaviors and evaluating what should be done in the future. We can inquire about specific moral standards that govern and influence right from wrong conduct and behaviors. Normative ethics also deals with what habits we need to develop, what duties and responsibilities we should follow, and the consequences of our behavior and its effects on others. Again, in a business or organizational context, we observe and address ethical problems and issues with individuals, teams, and leaders and address ways of preventing and/or solving ethical dilemmas and problems.

Descriptive ethics involves the examination of other people’s beliefs and principles. It also relates to presenting—describing but not interpreting or evaluating—facts, events, and ethical actions in specific situations and places. In any context—organizational, relationship, or business—our aim here is to understand, not predict, judge, or solve, an ethical or unethical behavior or action.

Learning to think, reason, and act ethically helps us to become aware of and recognize potential ethical problems. Then we can evaluate values, assumptions, and judgments regarding the problem before we act. Ultimately, ethical principles alone cannot answer what the late theologian Paul Tillich called “the courage to be” in serious ethical dilemmas or crises. We can also learn from business case studies, role playing, and discussions on how our actions affect others in different situations. Acting accountably and responsibly is still a choice.

Laura Nash defined business ethics as “the study of how personal moral norms apply to the activities and goals of commercial enterprise. It is not a separate moral standard, but the study of how the business context poses its own unique problems for the moral person who acts as an agent of this system.” Nash stated that business ethics deals with three basic areas of managerial decision making: (1) choices about what the laws should be and whether to follow them; (2) choices about economic and social issues outside the domain of law; and (3) choices about the priority of self-interest over the company’s interests.31

Unethical Business Practices and Employees

The 2020 Global Business Ethics Survey Report from the Ethics and Compliance Initiative (ECI) surveyed responses from 18 countries across global regions, including North America, South America, Europe, Asia Pacific, Africa, and the Middle East.32

Some Key Findings from the ECI:

• One in every five employees feels pressure to compromise their organization’s ethics standards, policies, or the law.

• Employees who feel pressure are about twice as likely to observe various types of misconduct.

• The incidence of pressure was three times as high for employees with weak leader commitment to organizational values and ethical leadership compared with strong leader commitment.

A 2014 National Business Ethics Survey (NBES)33 from the reputable Ethics Resource Center identified the types of ethical misconduct that were reported in the United States.

Specific Types of Ethical Misconduct Reported

The most frequently observed types of misconduct were a worker witnessing abusive behavior (18 percent), lying to employees (17 percent), discrimination (12 percent), and sexual harassment (7 percent). Types of misconduct that were viewed less frequently include falsifying company financial data and public reports (3 percent) or bribing officials (2 percent). Many employees still do not report misconduct that they observe, and fear of retaliation is increasingly valid. This retaliation can lead to instability in the workplace by driving away talented employees. Even with increasing investment in ethical programs, the rate of reporting was still within the range of 63 to 65 percent. Detailed data suggests that a potential factor is employees independently attempting to create a solution without the involvement of management.34

The Retaliation Trust/Fear/Reality Disconnect

Of the employees who reported witnessing misconduct in the 2014 NBES, approximately 20 percent experienced retaliation. Those companies that practice good business ethics will reap strong results in the future. It provides comfort to employees to speak out on matters, as shown by these statistics: “Reporting rates are higher (72 percent) at companies where the employee thinks retaliation is not tolerated compared to those who think retaliation is tolerated (54 percent).”35 Even in a scenario where an employee misses an initial opportunity to report misconduct, evidence suggests an improving situation. The willingness for employees who are victims of retaliation to report misconduct in the future was 86 percent (compared to the 95 percent of people who did not suffer retaliation but would report it in the future).36

An emphasis on and teaching of business ethics is slowly but surely producing positive results and has a strong impact on the company as a whole. The NBES report also made recommendations to help improve the business ethics of the workplaces:

• Maintain commitment to ethics and compliance program and seek industry leadership.

• Focus on efforts to empower employees and deepen their commitment to the company and its long-term success.

• Develop ongoing programs and structures to monitor misconduct within the company.

• Develop initiatives to address the most common forms of misconduct.

• Educate workers about Dodd-Frank and other laws designed to encourage whistle-blowers and protect them from retaliation.37

Why Does Ethics Matter in Business?

“Doing the right thing” matters to firms, taxpayers, employees, and other stakeholders, as well as to society. To companies and employers, acting legally and ethically means saving billions of dollars each year in lawsuits, settlements, and theft. One study found that the annual business costs of internal fraud range between the annual gross domestic product (GDP) of Bulgaria ($66 billion) and that of Taiwan ($586 billion). It has also been estimated that theft costs companies $600 billion annually, and that 79 percent of workers admit to or think about stealing from their employers. Other studies have shown that corporations have paid significant financial penalties for acting unethically.38 The U.S. Department of Commerce noted that as many as one-third of all business failures annually can be attributed to employee theft. “Potential global loss from fraud and employee theft is $2.9 trillion annually. It is also estimated that 33 percent of corporate bankruptcies in the United States are linked to employee theft.39

Relationships, Reputation, Morale, and Productivity

Costs to businesses also include deterioration of relationships; damage to reputation; declining employee productivity, creativity, and loyalty; ineffective information flow throughout the organization; and absenteeism. Companies that have a reputation for unethical and uncaring behavior toward employees also have a difficult time recruiting and retaining valued professionals.

Integrity, Culture, Communication, and the Common Good

Strong ethical leadership goes hand in hand with strong integrity. Both ethics and integrity have a significant impact on a company’s operations. “History has often shown the importance of ethics in business—even a single lapse in judgment by one employee can significantly affect a company’s reputation and its bottom line. Leaders who show a solid moral compass and set a forthright example for their employees foster a work environment where integrity becomes a core value.”40

Integrity/Ethics

What is the degree to which coworkers, managers, and senior leaders display integrity and ethical conduct? ECI data suggests that companies have been reinforcing the importance of integrity/ethics; namely, 47 percent of U.S. respondents in 2018 reported that they have “personally observed conduct that violated either the law or organization standards.” This number dropped from 51 percent reported four years earlies. Of the 47 percent of people, 69 percent of them reported a misbehavior, an all-time high and 23 percent increase since the first study, which was done in 2020. Some reported ethical acts included stealing, sexual harassment, misuse of confidential information, and giving or accepting bribes.41

The same study also identifies an important aspect of improving “employee conduct” in culture—which is defined as “the shared understanding of what really matters in an organization and the way things really get done.” While a strong culture provides many benefits, unfortunately, only 20 percent of respondents were confident that their company has a strong ethical culture. In an attempt to resolve this issue, suggestions on how to improve workplace ethical culture included the following: “(1) Promote a statement of values throughout the organization and set ethical standards to guide employee actions. (2) Include ethics and compliance in performance goals. (3) Regularly survey employee attitudes about pressures to disregard ethics. (4) Assess the ethical culture in the company and provide support in areas it may be weak. (5) Reinforce cultural norms of the unacceptability of performance without integrity. (6) Make sure company ethics and compliance programs are of high quality.”42

Working for the Best Companies

Employees care about ethics because they are attracted to ethically and socially responsible companies. Fortune magazine regularly publishes a list of the 100 best companies to work for. Although the list continues to change, it is instructive to observe some of the characteristics of good employers that employees repeatedly cite.

Over 252,000 employees at 257 firms doing business in 45 international participated in the 2020 survey. Companies were surveyed by the Great Place to Work Institute, a global research and consulting firm operating in 45 countries around the world. Sixty-six percent of the survey is based on the institute’s “Trust Index” survey, which relates to employees attitudes about “management’s credibility, job satisfaction, and camaraderie.” Thirty-three percent relates to a “Culture Audit” (i.e., pay and benefit programs, hiring practices, communication, training, recognition programs, and diversity efforts).43

The public and consumers benefit from organizations acting in an ethically and socially responsible manner. Ethics matters in business because all stakeholders stand to gain when organizations, groups, and individuals seek to do the right thing, as well as to do things the right way. Ethical companies create investor loyalty, customer satisfaction, and business performance and profits.44 The following section presents different levels on which ethical issues can occur.

1.3 Levels of Business Ethics

Because ethical problems are not only an individual or personal matter, it is helpful to examine where issues originate and how they change. Business leaders and professionals manage a wide range of stakeholders inside and outside their organizations. Understanding these stakeholders and their concerns will facilitate our understanding of the complex relationships between participants involved in solving ethical problems.

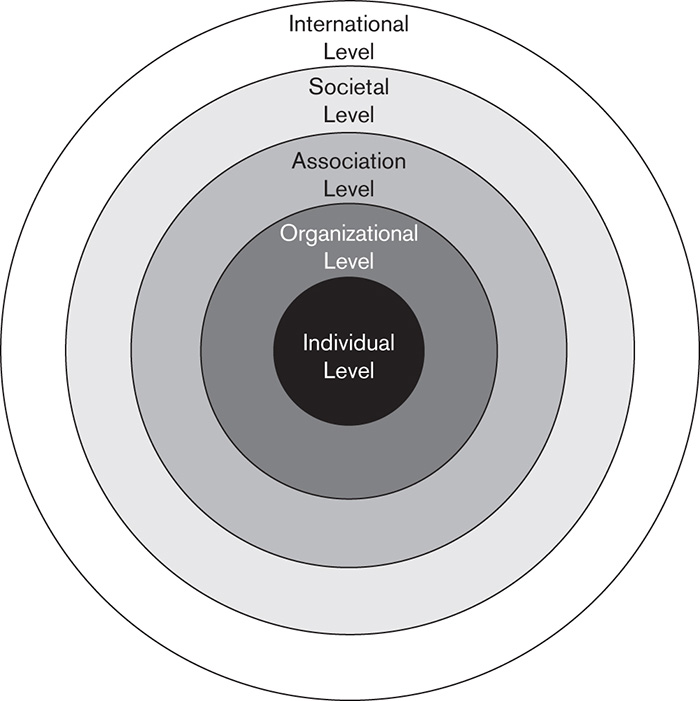

Ethical and moral issues in business can be examined on at least five levels. Figure 1.3 illustrates these five levels: individual, organizational, association, societal, and international.45

Figure 1.3

Business Ethics Levels

Source: Carroll, A. B. (1978). Linking business ethics to behavior in organizations. SAM Advanced Management Journal 43(3): 7. Reprinted with permission from Society for Advancement of Management, Texas A&M University, College of Business.

POINT/COUNTERPOINT

Can Ethics Really Be Taught?

Instructions: Take either one side or the other, Point or CounterPoint, in this exercise. Choose the side you feel the most comfortable with, not how you feel others might think of you or what you wish you could or should do. You’ll gain more learning this way. This exercise isn’t done to impress; it is designed for you to hear yourself, then others.

POINT: Ethics can’t really be taught—it’s part intuition, part beliefs, and part choice. Best to think about and study it, but then go with whatever the situation requires you to do and with what you can and are able to.

COUNTERPOINT: If you don’t decide by principle(s), then learning ethical ones and practicing with cases, discussion, and reflection will help you. Intuition may not work in a tough or crisis situation. Besides, do you really trust yourself to do “the right thing” under pressure or even in ordinary situations?

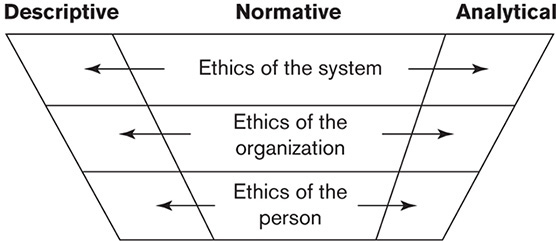

Figure 1.4

A Framework for Classifying Ethical Issues and Levels

Source: Matthews, J. B., Goodpaster, K. E., and Nash, L. L. (1985). Policies and persons: A casebook in business ethics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 509. Reproduced with permission from Kenneth E. Goodpaster.

Asking Key Questions

It is helpful to be aware of the ethical levels of a situation and the possible interaction between these levels when confronting a question that has moral implications. The following questions can be asked when a problematic decision or action is perceived (before it becomes an ethical dilemma):

• What are my core values and beliefs?

• What are the core values and beliefs of my organization?

• Whose values, beliefs, and interests may be at risk in this decision? Why?

• Who will be harmed or helped by my decision or by the decision of my organization?

• How will my own and my organization’s core values and beliefs be affected or changed by this decision?

• How will I and my organization be affected by the decision?

Figure 1.4 offers a graphic to help identify the ethics of the system (i.e., a country or region’s customs, values, and laws); your organization (i.e., the written formal and informal acceptable norms and ways of doing business); and your own ethics, values, and standards.

In the following section, popular myths about business ethics are presented to challenge misconceptions regarding the nature of ethics and business. You may take the “Quick Test of Your Ethical Beliefs” before reading this section.

Ethical Insight 1.1

Quick Test of Your Ethical Beliefs

Answer each question with your first reaction. Circle the number, from 1 to 4, that best represents your beliefs, where 1 represents “Completely agree,” 2 represents “Often agree,” 3 represents “Somewhat disagree,” and 4 represents “Completely disagree.”

1. I consider money to be the most important reason for working at a job or in an organization. 1 2 3 4

2. I would hide truthful information about someone or something at work to save my job. 1 2 3 4

3. Lying is usually necessary to succeed in business. 1 2 3 4

4. Cutthroat competition is part of getting ahead in the business world. 1 2 3 4

5. I would do what is needed to promote my own career in a company, short of committing a serious crime. 1 2 3 4

6. Acting ethically at home and with friends is not the same as acting ethically on the job. 1 2 3 4

7. Rules are for people who don’t really want to make it to the top of a company. 1 2 3 4

8. I believe that the “Golden Rule” is that the person who has the gold rules. 1 2 3 4

9. Ethics should be taught at home and in the family, not in professional or higher education. 1 2 3 4

10. I consider myself the type of person who does whatever it takes to get a job done, period. 1 2 3 4

Add up all the points. Your Total Score is: ______

Total your scores by adding up the numbers you circled. The lower your score, the more questionable your ethical principles regarding business activities. The lowest possible score is 10, the highest 40. Be ready to give reasons for your answers in a class discussion.

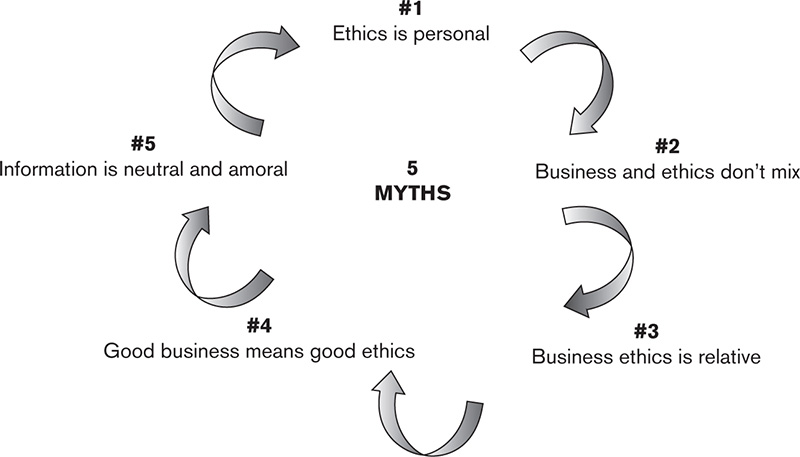

1.4 Five Myths about Business Ethics

Not everyone agrees that ethics is a relevant subject for business education or dealings. Some have argued that “business ethics” is an oxymoron or a contradiction in terms. Although this book does not advocate a particular ethical position or belief system, it argues that ethics is relevant to business transactions. However, certain myths persist about business ethics. The more popular myths are presented in Figure 1.5.

A myth is “a belief given uncritical acceptance by the members of a group, especially in support of existing or traditional practices and institutions.”46

Myths regarding the relationship between business and ethics do not represent truth but popular and unexamined notions. Which, if any, of the following myths have you accepted as unquestioned truth? Which do you reject? Do you know anyone who holds any of these myths as true?

Myth 1: Ethics Is a Personal, Individual Affair, Not a Public or Debatable Matter

This myth holds that individual ethics is based primarily and often only on personal or religious beliefs and that one decides what is right and wrong in the privacy of one’s conscience. This myth is supported in part by Milton Friedman, a well-known economist, who views “social responsibility,” as an expression of business ethics, to be unsuitable for business professionals to address seriously or professionally because they are not equipped or trained to do so.47

Figure 1.5

Five Business Ethics Myths

Although it is true that individuals must make moral choices in life, including business affairs, it is also true that individuals do not operate in a vacuum. Individual ethical choices are most often influenced by discussions, conversations, and debates and made in group contexts. Individuals often rely on organizations and groups for meaning, direction, and purpose. Moreover, individuals are integral parts of organizational cultures, which have standards to govern what is acceptable. Therefore, to argue that ethics related to business issues is mainly a matter of personal or individual choice is to underestimate the role organizations play in shaping and influencing members’ attitudes and behaviors.

Studies indicate that organizations that act in socially irresponsible ways often pay penalties for unethical behavior.48 In fact, the results of the studies advocate integrating ethics into the strategic management process because it is both the right and the profitable thing to do. Corporate social performance has been found to increase financial performance. One study notes that “analysis of corporate failures and disasters strongly suggests that incorporating ethics in before-profit decision making can improve strategy development and implementation and ultimately maximize corporate profits.”49 Moreover, the popularity of books, training, and articles on learning organizations and the habits of highly effective people among Fortune 500 and 1000 companies suggests that organizational leaders and professionals have a need for purposeful, socially responsible management training and practices.50

Myth 2: Business and Ethics Do Not Mix

This myth holds that business practices are basically amoral (not necessarily immoral) because businesses operate in a free market. This myth also asserts that management is based on scientific rather than religious or ethical principles.51

Although this myth may have thrived in an earlier industrializing U.S. society and even during the 1960s, it has eroded over the past two decades. The widespread consequences of computer hacking on individual, commercial, and government systems that affect the public’s welfare, like identity theft on the Internet (stealing others’ Social Security numbers and using their bank accounts and credit cards), and of kickbacks, unsafe products, oil spills, toxic dumping, air and water pollution, and improper use of public funds have contributed to the erosion. The international and national infatuation with a purely scientific understanding of U.S. business practices, in particular, and of a values-free marketing system has been undermined by these events. As one saying goes, “A little experience can inform a lot of theory.”

The ethicist Richard DeGeorge has noted that the belief that business is amoral is a myth because it ignores the business involvement of all of us. Business is a human activity, not simply a scientific one, and as such, it can be evaluated from a moral perspective. If everyone in business acted amorally or immorally, as a pseudoscientific notion of business would suggest, businesses would collapse. Employees would openly s