CHAPTER 1

THE EVOLUTION OF COMPASSION

I’VE BEEN exploring, studying, and teaching compassion my whole life. As a child, I lost track of how many times my parents admonished me by saying, “How would you feel if someone did that to you?” As I got a little older, the message changed to “Show some compassion” or “Walk a mile in their shoes.” I learned that compassion meant showing empathy and practicing the Golden Rule.

I grew up as a Mennonite missionary kid in Africa. My father was a farmer from Kansas who got an advanced degree in animal husbandry and sought to solve the problem of protein deficiency among Congolese tribes in tropical climates. My mother was a nurse, helping solve the problems of malnutrition, disease, and poor hygiene. I learned that compassion meant alleviating suffering.

During my high school years in southern Africa in the 1980s, I saw firsthand the injustice and violence of racism and apartheid. Nelson Mandela, who held a vision of reuniting South Africa under a truly representative democracy, was in prison on Robben Island. I remember struggling with the pacifist teachings of my Mennonite faith. How could I respond to violence with kindness when everything is unjust and evil? When I turned eighteen I was required to register for the draft since I was a US citizen, even though I lived in Botswana. I registered as a conscientious objector, doing my best to articulate my support for my country but resistance to participating in war. I was taught that compassion meant avoiding violence and turning the other cheek.

I returned to America in 1985 to attend Bethel College, a small Mennonite liberal arts college in central Kansas. This experience opened my mind to different perspectives, engaged my critical thinking, and invited me to challenge my own beliefs. In this environment I learned that compassion meant being open-minded and tolerant of diversity.

My graduate training in clinical psychology at the University of Kansas during the early 1990s included a mediation certificate. When I was practicing mediation with a feuding couple, success meant finding a solution that both parties could live with and avoiding going to court. I learned that compassion meant finding a workable compromise.

As a clinical psychologist trained in the late 1990s, I was taught to show unconditional acceptance; be a “safe, nonanxious presence”; and attend to my client’s feelings. Compassion in the therapy space meant helping clients feel safe, cared for, and valuable as human beings.

In the early 2000s I helped start an integrated behavioral medicine clinic at a regional hospital and discovered two more sides to compassion. As a liaison consultant within the healthcare environment, compassion meant coordinating care across diverse disciplines to keep the whole person at the center of it all.

At the same time, the mindfulness and meditation movement was hitting prime time, pioneered by the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. I studied many of these emerging techniques and applied them in my treatment with patients who struggled with chronic, relapsing medical conditions. This movement has continued to evolve and grow. Now you can choose from dozens of smartphone apps that guide daily meditations and self-compassion exercises. In this context, compassion meant non-judgmental self-acceptance, presence, and self-care.

In 2008 I left clinical practice to start a professional leadership development company, motivated by the desire to make a bigger difference in a different context. I had been managing a multistate employee assistance program and noticed the prevalence of mental health problems in the workplace. I knew that most of the affected employees would never get professional mental health support but still needed the kind of help they weren’t getting anywhere else. I also noticed how toxic many workplaces were. Employees didn’t feel valued, leaders were overworked and caught between too much responsibility and too little authority, and corporate profit seeking was increasing income disparity. The 2008 recession only compounded these dynamics. Compassion in this context seemed pretty basic: treat your employees with fairness and dignity.

I feel so fortunate that the behavioral health organization in which I worked had an adventure ropes course. I seized the opportunity to get trained as an adventure course facilitator and started facilitating team building with corporate teams, students, and other community groups. Using an experiential process with teams to build cohesion, trust, and problem-solving skills was so rewarding. I saw potential for transformation within leaders, teams, and cultures and wanted to be part of that on a larger scale. I was fortunate to be trained and mentored by some of the greats in the adventure industry: Karl Rohnke, Tom Leahy, Michelle Cummings, Michael Gass, and the Project Adventure organization.

On the adventure course was the first place I began to experience the accountability aspect of compassion. On a high ropes course or even during an experiential learning activity on the ground, people need a balance of supportive acceptance and attention to boundaries and principles. A person’s safety often depends on it. In this context, I experienced the tension between psychological safety and accountability for self-care. Whether doing a trust fall or helping your teammate scale a twelve-foot wall, each person must take 100 percent responsibility for their behaviors and roles while adhering to critical physical safety guidelines. At the same time, if people don’t take absolute care of the psychological safety and acceptance of another’s experience, participants can end up in risky situations or emotionally traumatized by the experience.

As an aside, the experiences that my partners and I shared on adventure courses at a previous employer before starting Next Element are part of what inspired the name of our company. A typical adventure course contains a variety of elements, each one designed to enable specific, positive growth experiences. A group will move from element to element depending on its goals for the experience. Facilitators often asked the group, “Are you ready to go to the next element?” We used to have a secret challenge among ourselves to see who could work in the phrase next element most often during the day without any clients knowing it.

Early on in my career as a clinical psychologist, I experienced the push for results. I was responsible for meeting quality and performance goals, completing documentation on time, and keeping my credentials current. As I began taking on leadership roles, I took on the added responsibility of holding others accountable for these same results. In these positions, I first began to appreciate that building connections and getting results go hand in hand. Compassion and accountability are not opposites; they should not compete with each other. Viewing them as such can take a leader down an unproductive path.

Since founding Next Element in 2008, we’ve gone all in on compassion. Our mission is to bring more compassion to the world. We’ve continued to study and explore what it means to be compassionate and how to make compassion accessible to more people. Over the years, we’ve seen a distinct progression in the way compassion is viewed and practiced in the workplace. We have struggled within our own company to reconcile connection and results.

Compassion’s Journey

Compassion has been on an interesting journey over the last decade. I’ve segmented this journey into five eras: self-compassion, business compassion, inclusion compassion, pandemic compassion, and compassionate accountability. The date ranges are not absolute, and plenty of overlap exists between the eras. The main point is to capture how our relationship with compassion at work and in leadership has changed over time. See if you can relate to these shifts. Where were you in your journey as a leader during these eras? How did you experience these dynamics? Did you experience tension between connection and results?

Self-Compassion (before 2008)

Prior to the mid-2000s, compassion was seen as a personal practice, something that individuals could use to reduce stress, be more healthy, and expand their consciousness. Historical figures such as Mother Teresa, Gandhi, and the Dalai Lama were lifted up as models of compassion. Some workplaces recognized the importance of self-compassion, and some even supported their employees to pursue personal compassion practices under the banner of stress management or general wellness. But for the most part, compassion was a personal practice, or reserved for our heroes, not an integral part of corporate culture. Thankfully, research continues to show the benefits of compassion on wellness, and views have changed.

Business Compassion (2008 to Present)

A 2008 study on workplace conflict conducted by CCP Inc. found that US companies spent more than 2.8 hours per week dealing with conflict, which equated to approximately $359 billion in paid hours in 2008. In many cases, this severely crippled productivity and morale.1

At the height of the Great Resignation during the COVID-19 pandemic, newer research reported in the MIT Sloan Management Review showed that toxic workplace culture is over ten times more important in driving people to leave their jobs than compensation.2

Toxic cultures are rife with negative conflict where employees don’t feel safe, empowered, or motivated. One of the biggest complaints of employees working in toxic work environments is that productivity and profit always get top priority at the expense of people and relationships.

Compassionate capitalism, as described in Blaine Bartlett’s 2016 book, is a reaction to this trend. Bartlett blames uncontrolled, free-market capitalism for the rise of toxic work cultures. Results have become the only goal, and consequently, connection to others and the world in which we live has been lost. This has led to accountability without compassion. As an alternative, he promotes a model driven by enlightened self-interest, which balances business success with human and environmental consciousness.3

He argues that enlightened self-interest actually produces better, more sustainable business outcomes while strengthening relationships between people and between humans and their environment—thus, accountability with compassion.

As data has accumulated on the negative impact of toxic work cultures on engagement, retention, productivity, and profitability, attention has turned toward how to humanize the workplace for better business results. Awakening Compassion at Work, by Jane Dutton and Monica Worline and published in 2017, offers a great synopsis of the research showing that strong relationships and respect for individuals can drive positive business results.4

In 2020 the Harvard Business

Review published a summary of the literature showing that compassion in leadership improves collaboration, raises levels of trust, and enhances loyalty.5

One promising healthcare-focused study showed that relational leadership practices, which include more compassion within the leadership culture, can have a stronger and more sustainable positive impact than tactical interventions, such as increased pay or flexible work schedules.6

Companies such as Google and LinkedIn led the early charge in creating more human-centered work environments. Google’s research on team effectiveness showed that psychological safety was a key ingredient in high-performing teams.7

LinkedIn was one of the pioneers in the movement to make compassion a central part of the workplace experience. Jeff Weiner was the CEO of LinkedIn from 2009 to 2020. He is regarded as one of the pioneers of compassionate workplaces for his systematic efforts to embed it into the culture. In 2018 Jeff appointed Scott Shute as head of Mindfulness and Compassion Programs, signaling a serious commitment to the philosophy that compassion is not only the right thing to do but also good for business. Scott’s book, The Full Body Yes, articulates some of the principles he helped develop and teach at LinkedIn.8

The business compassion era helped us realize that a lack of compassion hurts business, while more compassion can help businesses realize even greater success without the negative consequences.

Inclusion Compassion (2017 to Present)

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives encourage self-awareness, cultural competency, and empathy in employees, addressing unconscious bias as well as promoting an overall safe, welcoming workplace environment. Diversity initiatives have been growing since long before 2017, but in the last several years, a focus on equity and inclusion has become a mainstream movement in corporate culture.

Gloria Cotton, one of the most respected voices for inclusion, defines inclusion this way: “Being a pro-inclusionist means creating specific actions to help every person feel welcomed, valued, respected, heard, understood and supported.”9

Inclusion compassion is about recognizing the inherent value and contribution of all human beings and then taking steps to make this a reality in the workplace. Although organizations are implementing DEI within a range of levels, it’s nearly impossible to be considered a leading employer without a well-developed DEI program, including appointing a top executive-level inclusion officer. Fortune is one of the most prominent publications that has added a ranking for companies based on their DEI efforts. This era positioned compassion as a foundation for inclusion.

Pandemic Compassion (2020 to 2021)

On January 9, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced a mysterious coronavirus-related pneumonia, first found in Wuhan, China. The first confirmed case in the United States was on January 21, 2020. On January 31, WHO announced a world health emergency. On February 3, the United States declared a public health emergency, and by March 11, WHO had officially announced COVID-19 as a pandemic.

Crisis can bring people together. Despite the political rhetoric, the one thing we all had in common was that we were afraid. “We are in this together” became the anthem. Somehow, when people are going through something difficult, just knowing we aren’t alone can help tremendously. For a short time, the pandemic brought the world together in spirit.

The word compassion originates from the Latin root meaning “to suffer or struggle with.” Worrying that the pandemic was probably going to get worse before it got better, and without a solution in sight, all we had was our shared suffering. Those were the good old days. Compassion took a big swing as the pandemic continued.

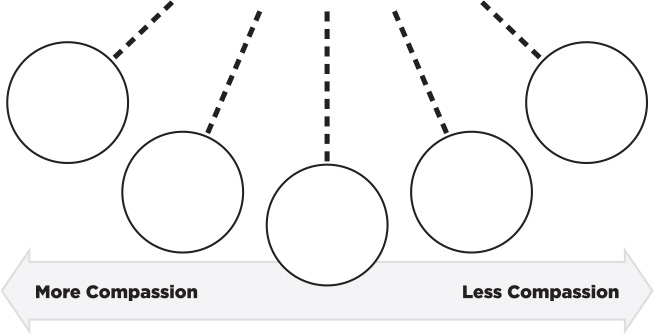

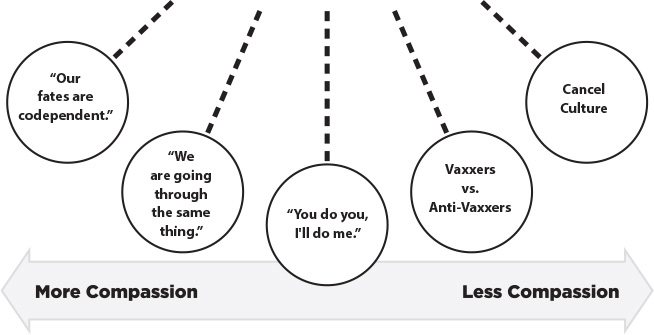

First, imagine a pendulum of compassion as shown in figure 1.1. A swing to the left represents more compassion. A swing to the right represents less compassion. We could apply this lens to any situation by asking ourselves, “What would it look like to respond with more compassion? Less compassion?”

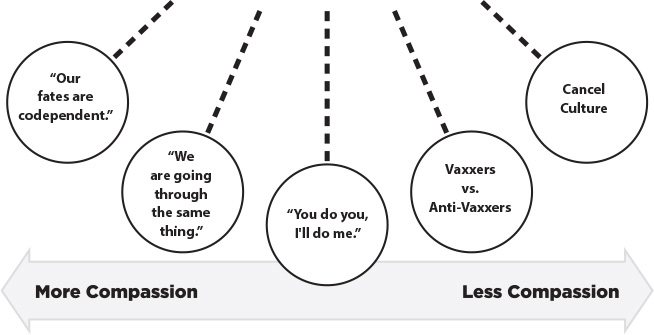

March through June 2020 were the good old days for compassion. “We’re all in this together” was the anthem. This represents a moderate level of compassion since it recognizes that others are also suffering and that we have something in common, something that unites us.

But how fast we can change and swing to the other extreme. Consider cancel culture: it has become common, almost normal, to viciously attack someone, attempt to destroy their reputation, or even resort to physical violence simply because we don’t agree with their position or like their perspective on something. My belief is that cancel culture was made possible by the combination of ubiquitous and powerful social media, coupled with high-profile and influential leaders who modeled a willingness to use it as a weapon to further their own selfish agendas. This twisted attempt at accountability harbors no compassion.

FIGURE 1.1. The pendulum of compassion. Designed by Scott Light, CG Studios.

Let’s take a look at how the pendulum swung during the first two years of the pandemic in figure 1.2.

I witnessed this firsthand a couple of years ago in my hometown. A local educator was accused of sexually assaulting a student. The investigation did not result in any formal charges, so some members of the community took matters into their own hands, launching a public cancel campaign against this person. The polarization caused by the publicity made it nearly impossible to engage in meaningful dialogue or pursue any form of restorative justice. This is an example of accountability without compassion.

Applying this to the pandemic, we saw extreme hatred and attacks between ideological groups formed around their beliefs about the virus, the cause, the vaccine, or how different groups should be treated. The vaxxer versus anti-vaxxer war ensued for nearly two years, with each side continually trying to discredit and vilify the other. Research showed significant differences along political party lines regarding vaccination status and beliefs about the virus. This certainly is evidence of less compassion since it focuses on differences rather than commonalities. How quickly we went from “We are all in this together” to “You are a threat to our democracy since you don’t agree with my position on COVID-19.”

FIGURE 1.2. The pendulum of compassion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Designed by Scott Light, CG Studios.

And then we have that in-between place, where compassion is neither noticeably present nor absent. The pendulum is at dead center.

I was a member of my church’s elder leadership team from 2019 to 2021. During that time we agonized around the same issues every organization faced: How can we continue our mission and stay operational during the pandemic?

In fall 2021 we lifted the mask requirement in our church, leaving it open to personal choice. The next Sunday I showed up for church still wearing my mask. Among a couple dozen people who showed up that Sunday, I was one of only two who were wearing a mask. I was worried about being judged because I was in the minority. But it didn’t happen. I didn’t sense any negative energy in my interactions. I also didn’t get any support. Nothing was said one way or the other.

The problem with the in-between place is that we basically allow people to do their thing, with an unspoken agreement not to say anything: “You do you, I’ll do me” or “Let’s agree to disagree.” It’s a no-man’s-land where people coexist but without the intimacy and connection that comes when we embrace our interdependency and engage in healthy conflict.

The Solution: Compassionate Accountability

Compassion is so much more than most of us imagine or have experienced. I consider myself fortunate to have learned and experienced so many aspects of compassion—though even that learning was incomplete.

Compassion isn’t just tolerance, safety, caring, empathy, alleviation of suffering, kindness, nonviolence, or even inclusion. Compassion means truly embracing that our fates are codependent. We aren’t just going through the same trials, we truly are in this together. My actions affect you. Your actions affect me. My thoughts, beliefs, and feelings have a powerful impact on the world around me, and so do yours. Our world is inextricably connected. We get the biggest and best results through our connections, not in spite of them.

Compassion is what makes us human, keeps us on track, and brings us back together when we’ve lost our way.

Just being nice doesn’t cut it. Compassion without accountability doesn’t address the tough issues we are facing, nor does it acknowledge the inherent conflict when attempting to bring diverse viewpoints and skill sets together to solve big problems. Similarly, accountability without compassion results in toxic cultures that focus only on the endgame at the expense of people and relationships.

The next evolution of compassion is Compassionate Accountability.

Tom Henry, former learning and development coordinator at Whole Foods Market, has been heavily involved in the conscious capitalism movement. During an interview for my podcast, Tom shared with me one of the primary tenets of conscious capitalism, conscious culture, which implies and affirms, “We are in this together.”10

He went on to explain, “We are not separate individuals, we are a collective consciousness. Our fate as human beings is interdependent, so how we view and treat each other is critical to our survival and our ability to thrive.” This idea is consistent with Charles Darwin’s discovery that species who work together and depend on one another during tough times are more likely to survive and thrive.

Darwin’s discovery applies even to the biggest organizations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the WD-40 Company thrived and grew stronger thanks to its culture of compassion characterized by a safe and strong team-focused environment, transparent communication, consistent high standards, and leaders who modeled the company’s values. WD-40 already had a long track record of success, but when many global organizations were struggling to survive and keep great talent, engagement at WD-40 went up to an all-time high. In 2021 98 percent of employees said they were excited to work there.

Garry Ridge, chairman and CEO of WD-40 for twenty-five years and up through the pandemic, credits its success to the company’s compassionate culture, based on Garry’s philosophy that a tribe is more successful than a team. Garry explained to me, “A team is something you play on. A tribe is something you belong to, like a family. Tribes feed and protect each other. Teams come and go, but tribes thrive over the long term.” In his latest book, The Unexpected Learning Moment: Lessons in Leading a Thriving Culture through Lockdown 2020, Garry shares more specifics about how compassionate cultures can help organizations thrive during crisis.11

Dr. Rob McKenna, founder of WilD Leaders, is an industrial and organizational psychologist and leadership expert focusing on leading under pressure, with clients including Boeing, Microsoft, Heineken, and United Way. In my conversations with Rob, he has shared his deep conviction that we are in an unprecedented time in which whole and intentional leadership development matters.12

We need leaders who can balance peacekeeping with truth speaking, lead with a sense of purpose, and see capability and potential instead of barriers.

Now more than ever, we need to bring compassion and accountability together, embracing both in full measure. Without it, the pendulum will keep swinging or, even worse, get stuck. If we want a better future and better companies, we need to invite people to prepare for this.