Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Creating an Environment for Successful Projects, 3rd Edition 3rd Edition

Randall Englund (Author) | Robert J. Graham (Author)

Publication date: 10/01/2019

For over twenty years, Creating an Environment for Successful Projects has been a staple for upper managers who want to help projects succeed. This new edition includes case studies from companies that have successfully applied the approach, along with practical tools such as templates, surveys, and benchmark reports for savvy leaders who want to ensure project success throughout their organizations. The insights in this book will help management speed projects along instead of getting in their way. All too often, well-intentioned managers put roadblocks in the team's way instead of empowering them with the tools they need to succeed. This approach to project environments, grounded in decades of research and practice, will help you make your organization the most project-friendly it's ever been.

Organizational changes rarely work unless upper management is heavily involved. Although project managers are most closely responsible for the success of projects, upper managers are the ones who ultimately create an environment that supports those projects. The way upper managers define, structure, and act toward projects has an important effect on the success or failure of those projects and, consequently, the success or failure of the organization. This book helps all managers understand the need for project management changes and shows how to develop project management as an organizational practice.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

For over twenty years, Creating an Environment for Successful Projects has been a staple for upper managers who want to help projects succeed. This new edition includes case studies from companies that have successfully applied the approach, along with practical tools such as templates, surveys, and benchmark reports for savvy leaders who want to ensure project success throughout their organizations. The insights in this book will help management speed projects along instead of getting in their way. All too often, well-intentioned managers put roadblocks in the team's way instead of empowering them with the tools they need to succeed. This approach to project environments, grounded in decades of research and practice, will help you make your organization the most project-friendly it's ever been.

Organizational changes rarely work unless upper management is heavily involved. Although project managers are most closely responsible for the success of projects, upper managers are the ones who ultimately create an environment that supports those projects. The way upper managers define, structure, and act toward projects has an important effect on the success or failure of those projects and, consequently, the success or failure of the organization. This book helps all managers understand the need for project management changes and shows how to develop project management as an organizational practice.

—Lewis E. Platt, former Chairman, President, and CEO, Hewlett-Packard Company

“Creating an Environment for Successful Projects is an outstanding resource for any organization, team, or individual responsible for delivering projects effectively. We have used the authors' experiences and knowledge to workshop the needs in our organization and continue to develop tactics to further enhance our project management practices. This book will remain on my shelf as a reference for our future.”

—James A. Lee, PE, LEED AP, President, Shive-Hattery

“The first edition was so valued that it was stolen from my NASA office after I told others that it was one of the finest project leadership books around. Glad to see that the third edition is coming out.”

—Edward J. Hoffman, PhD, former Chief Knowledge Officer, NASA; CEO, Knowledge Strategies; Strategic Advisor, PMI; and Senior Lecturer, Columbia University School of Professional Studies

“Creating an Environment for Successful Projects became our bible for program leadership during PMO startup and continues to be a fundamental part of our thinking as we work to attain recognition as a truly project-based organization.”

—Colonel Gary LaGassey, former Project Office Program Manager, Aviano Air Base, Italy

“The book is rich with examples of why typical management behavior interferes with new product development. It clearly explains why upper managers are fearful, why corporate communications are so often poor, and yes, how to fix such things. The goal is to give project managers the freedom, training, and support to run rather autonomous and effective new product development programs.”

—John D. Trudel, Journal of Management Consulting

CHAPTER ONE

Leading Change to a Project-Based Organization

When all the conditions of an event are present, it comes to pass.

HEGEL, PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Most future growth in organizations will result from successful development projects that generate new products, services, or procedures. Such projects are also a principal way of creating organizational change; implementing change and growth strategies is usually entrusted to project managers. However, project success is often as much a result of the organizational environment as of the skills of the project manager. As the size and importance of projects increase, the project manager becomes the head of a complex development operation with an organizational dimension that can make important contributions to project success or failure. That this organizational dimension may help explain project performance has been strangely neglected in the literature, a problem we address here by examining the role of upper management in creating an environment that promotes project success.

All too commonly, people become project managers by accident. One way to become a project manager is to ask a question at a meeting and then be told, “That’s a good question. Why don’t you take on the project of dealing with that problem?” Or somebody comes up with an idea and is tapped to make it happen, or the generator of the idea looks around for the first person in sight to whom it can be assigned for implementation. Experience indicates that in the process of developing projects, upper managers often appoint inexperienced or accidental project managers (APMs), give them a project to manage, and then systematically undermine their ability to achieve success. Upper managers do not usually undermine APMs on purpose, but too often they apply assumptions and methods to project management that are more appropriate to regular departmental management. Projects are a totally different beast in many ways. Everyday management generally is a matter of repeating various standard processes; projects, in contrast, create something new.

In addition, upper managers are often unaware of how their behavior influences project success or failure. Because previous examinations of project success focus almost exclusively on the functions of the project manager, there is an understandable lack of awareness of the importance of the project environment and the behavior of middle and higher managers in organizations—those managers of project managers whom we refer to as upper managers. It is important to understand the impact of their behavior on the future survival of organizations. Roles and responsibilities are changing as organizations become organic and project based—that is, driven by internal markets and team accountability for specific results. Any lapses by upper managers in the authenticity and integrity of their dealings with project managers and with managers in other departments are likely to have a severe impact on the achievement of project goals.

Upper managers can emulate successful gardeners: best results occur when creating an environment for systems to perform the way they innately know how to.

A Scenario

Many upper managers voice increasing frustration with the results of projects undertaken in their areas of responsibility. They lament that despite sending people out for training and buying project management software, projects seem to take too long, cost too much, and produce less than the desired results. Why is that? To help understand the problem, consider the following scenario.

An upper manager gets an idea, perhaps from reading a book or attending a conference, and has a vision of a product or service that the organization can offer. This vision may differ from what the company normally provides, so creating the product becomes a special project. Talking it over with associates, the manager is delighted when one of the best engineers becomes interested. To get the concept rolling, the manager asks this engineer to manage the project. They both figure the project can be done quickly because the engineer has achieved good results on past work. The new project manager talks to a few colleagues, and soon a team of engineers begins working on the design. After a while, the team comes back to the upper manager with good news and bad news. The good news is that a certain technology needed for the project is available inside the organization; it was developed in another division, however, so the team needs to borrow a few people from there to get it. The bad news is that another needed technology is not available in the organization, so new people will have to be hired. The upper manager arranges to borrow people from the other division and authorizes hiring the needed employees from the outside.

Delay begins about here. The new employees must be approved by the executive committee and then must have job descriptions defined and developed by the personnel department. Because these new people know the latest technology, they are expensive; even so, it takes them longer than expected to become productive once they are on board because they are not used to the ways of their new employer. Eventually, however, the whole group gets working—until a manager from the other division, for which this special project is not a priority, takes back the borrowed engineers. Work slows again as the upper manager tries to negotiate their return. Some engineers are finally freed for the project, but they are not the original engineers and thus they lack the requisite skills, which results in more delays until they are brought up to speed.

When work finally resumes, questions arise about marketing the new product and about using patented technology to create it. The upper manager must therefore add people from the marketing and legal departments to the project. Sure enough, the lawyers ascertain that the new employees inadvertently used a technology patented by another company; the upper manager must determine whether it is cheaper to pay for its use or develop an alternative technology. Communication with the new project team members from marketing is difficult because marketing uses a different email system from that of the engineering and legal departments. Decision making is further delayed as upper managers argue over a number of manufacturing issues that came up on previous projects but were never resolved.

The team grows disgruntled as it becomes clear that the great engineer is not skilled in planning and conflict management; the situation is not improved when the engineer disappears for several weeks to fix problems that arose from a previous project. Elsewhere in the organization, people begin to grumble that the project is costing lots and accomplishing little. Some do not believe the project is a good idea. The upper manager spends time justifying the project to other department managers but cannot avoid finally being called before the executive committee to explain why it is taking so long and costing so much.

If this scenario seems at all far-fetched, consider this letter that one of us received:

I work in a planning and distribution organization. My duties include leading efforts that are called projects and generally I’m fixing a problem with a process or system. Rarely do I get due dates or objectives … and when I press my sponsor[s] on this point they tell me essentially that they just want it done. Coupled with this the department has difficulty achieving the full intent of the objectives, and we are pretty unproductive (we don’t get many projects completed in a year). We are putting together a proposal including development of dedicated project managers in the organization whose entire job is to lead the projects of the organization (as opposed to the current method of choosing people whose work is closely aligned to the project).

Unfortunately, some managers feel strongly that they do not want their resources utilized by the project managers (and subject to the project manager’s discretion). Plus, they want to have access to their people to pursue their own objectives (this includes assigning one of their people as project lead[er] regardless of skill). At this point we need help in convincing these managers to support the process of project management …

You can almost hear the voice trailing off in a sigh of frustration.

Another problem is the assumption that project work should take about as long as traditional work. This sets expectations that can never be met, so projects always seem slower and more costly than other activities. Actually, they should take longer; project work represents something new and different, so the inevitable unknowns, such as those in the scenario, need to be factored into the expected length. It is also a false assumption that project work can be handled in the same way as other work, using the same organization and the same people. In reality, because project work is different, it requires a project-based organization. The project in the scenario failed because upper management had not created an environment for project success.

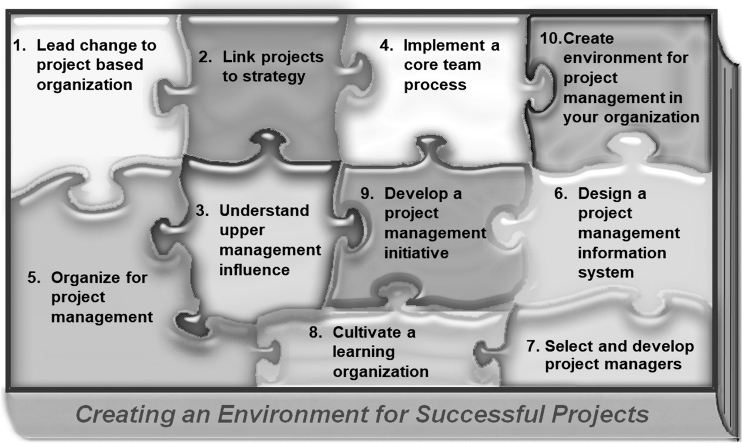

Creating an Environment for Successful Projects

What environmental components foster successful projects? Many misconceptions develop into folklore over time, such as the Humpty Dumpty nursery rhyme (see Box 1.1). The king’s men may not have been able to put Humpty’s pieces together, but the key pieces needed to create a picture of a supportive project environment (see Figure 1.1) can be readily assembled with this book as a guide.

A word of caution: the pieces we are assembling will not stay together without glue, and the glue has two vital ingredients: authenticity and integrity. Authenticity means that people really mean what they say. Integrity means that they really do what they say they will do, and for the reasons they stated initially. It is a recurring theme in this book that authenticity and integrity link the head and the heart, the words and actions; they separate belief from disbelief and often make the difference between success and failure.

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall

All the King’s Horses

And all the King’s Men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

The character in this nursery rhyme is usually represented as an egg that falls and breaks. In reality, a humpty dumpty was a type of military cannon. During a battle, it was put up on a wall. When the cannon was fired, the recoil sent it off the wall to the ground, where it came apart. The king’s horses were the cavalry, and the king’s men were the army. They were there to win the battle, but they couldn’t put Humpty the cannon together again: they were not able to put together all the pieces required for success.

Each of the ten pieces in the figure is the subject of a chapter in this book.

1. Lead Change to a Project-Based Organization. The balance of this chapter examines a process for changing organizations and discusses the requirements of change agents. Changing to a project-based organization requires changes in the behavior of upper managers and project managers. For example, a project-based organization must also be team based; to create such an organization, upper managers and project managers themselves need to work together as a team.

2. Link Projects to Strategy. It is important to link projects to strategy. Upper managers need to work together to develop a strategic emphasis for projects. One factor in motivating project team members is to show them that the project they are working on has been selected as a result of a strategic plan. If they instead feel that the project was selected on a whim, that nobody wants it or supports it, and that it will most likely be canceled, they will probably (and understandably) not do their best work. Upper managers can help avoid this problem by linking the project to the strategic plan and developing a portfolio of projects that implements the plan. Many organizations use upper management teams to manage the project portfolio; this approach would certainly have reduced the problems and delays depicted in the previous scenario.

Chevron, for example, developed the Chevron Project Development and Execution Process (CPDEP), which provides a formalized discipline for managing projects (Cohen and Kuehn, 1996). A key element of CPDEP is the involvement of all stakeholders at the appropriate time. In the initial process phase to identify and assess opportunities, a multifunctional team of upper managers meets to test the opportunity for strategic fit and to develop a preliminary overall plan. The project does not proceed from this phase unless there is a good fit with the overall strategy. Developing a process for selecting and managing a portfolio of projects is the subject of Chapter Two.

3. Understand Upper Management Influence. Many of the best practices of project management often fail to get upper management support. Many upper managers are unaware of how their behavior influences project success. To help ensure success, they are advised to develop a project support system that incorporates such practices as negotiating the project deadline, supporting the creative process, allowing time for and supporting the concept of project planning, choosing not to interfere in project execution, demanding no useless scope changes, and changing the reward system to motivate project work. These topics are considered in Chapter Three.

4. Implement a Core Team Process. A core team consists of people who represent the various departments necessary to complete a project. This team needs to be developed at the beginning of the project, and its members perform most effectively when they stay with the project from beginning to end. Developing a core team process and making it work are essential to minimizing project cycle time and avoiding unnecessary delays. Important as they are, however, core teams are rarely implemented well without the implicit and explicit support of upper management. Firms that have used core teams often report dramatic results. Cadillac (1991), for example, found that core teams can accomplish styling changes that previously took 175 weeks in 90–150 weeks. Developing a core team is the subject of Chapter Four.

5. Organize for Project Management. The revitalization process described in Chapter One provides the impetus in Chapter Five for determining how an organization may be changed to support proper project management. In the scenario earlier in this chapter, much of the delay can be attributed to the lack of an organizational design that supports project management. In contrast, the decentralized corporate culture of Hewlett-Packard (HP), as one example, gives business managers a great deal of freedom in tackling new challenges. Upper managers have a responsibility to set up organizational structures that support successful projects. Because structure influences behavior, Chapter Five reviews the characteristics of alternative organizational structures and examines what can be done to alleviate some of the problems caused by certain structures.

6. Design a Project Management Information System. In the past, organizational policies, procedures, and authority relationships held things together. The project-based organization lacks much of that structural framework; instead, the project organization is kept intact by an information system. For example, former HP executive vice president Rick Belluzzo (1996b) envisioned a “people-centric information environment that provides access to information anytime, anywhere … and that spurs the development of a wide range of specialized devices and services that people can use to enrich their personal and professional lives.” Upper managers need to work in concert to design information systems that support successful projects and provide information across the organization. In this regard, online technological capabilities are increasingly attractive and important but do not replace the need for upper management to determine what information is necessary and develop systems to provide it. Chapter Six covers this in depth.

7. Select and Develop Project Managers. Developed organizations will see the end of the APM. Project management needs to be seen as a viable position, not just a temporary annoyance, and project management skill needs to become a core organizational competence. This requires a conscious, planned program for project manager selection and training. HP, Computer Science Corporation, Keane, and 3M are among the companies that have spent large amounts on project manager training and development, as discussed in Chapter Seven. The development emphasis of these organizations seems justified because the project managers of today will become the leaders of the project-based organization of tomorrow. This is such an important topic that Bowen, Clark, Halloway, and Wheelwright (1994a) advise organizations to “make projects the school for leaders.”

8. Cultivate a Learning Organization. Chapter Eight summarizes the concepts of organizational learning as they apply to project-based organizations. One key to organizational learning is the post-project review, which helps project participants and the rest of the organization learn from project experiences. Although its value may be priceless and its cost nil, this learning process takes place only if upper managers set up a formal program and require the reviews. When they do, many tools for project improvement can be developed that can help eliminate frustrating delays. For example, British Petroleum (BP) has operated a post-project appraisal unit since 1977 (Gulliver, 1987), and BP managers attribute dramatic results to it. By learning from past projects, they say that they are much more on target in developing new project proposals, have a much better idea of how long projects take, and thus experience less frustration at perceived project delays. Learning from project experience becomes a major emphasis in project-based organizations and can be seen as a competitive advantage.

9. Develop a Project Management Initiative. HP had an ongoing initiative to continually improve its project management practices. Dubbed the Project Management Initiative, it was part of senior management’s breakthrough objective to get the right products to market quickly and effectively. An initiative group works with upper managers and project managers to increase project management knowledge and practice throughout the organization. Project management became very important to HP’s success because more than half of customer orders typically came from products it introduced within the previous two years. Shorter product life cycles mean more new projects are needed to maintain growth. Marvin Patterson, a former director of corporate engineering at HP, says, “Due to my experience since I left HP, I would say that HP probably has the best project managers in the world, or at least in this hemisphere. The Project Management Initiative made a huge contribution to this success” (personal conversation). The details of an initiative process are presented in Chapter Nine. This approach can be extrapolated into a more general project or program management office.

10. Create an Environment for Successful Projects in Your Organization. Chapter Ten provides suggestions for adapting and applying the concepts in this book to cultural environments that differ from those described herein. For example, Honeywell developed a global information technology project management initiative based on its chief information officer’s desire to have modern project management disciplines throughout Honeywell Information Systems be “the way of doing business” and a “core competency.” To accomplish this, the initiative group developed a project management focus group of fifteen people from different departments to discuss the basis of good project management. With input from this group, the initiative team developed a project management model, a project management process, and a supporting training and education curriculum; it also promotes a professional project manager certification process. The team’s vision was for Honeywell Information Systems to be recognized “as a world-class leader in modern Information Technology Project Management principles, processes, and practices” (Koroknay, 1996, p. x).

3M developed the Project Management Professional Development Center, which consisted of people and services from three information technology organizations. A center offers consulting help for project teams, research on the latest best practices and help in applying them, and a project management competency model supported by a project leader curriculum. It also sponsors a project leader forum, where project leaders can meet in person to share stories and problems. Communication is enhanced by an “electronic post office,” a communications network linking all project managers (Storeygard, 1995). These and other company efforts are detailed in Chapter Ten as a guide to developing better project management.

All these examples represent significant efforts on the part of major corporations to meet the challenge of developing project management expertise. Such major effort is needed because the change to project management means changing deeply ingrained habits of organizational behavior. Many cherished and highly rewarded practices need to be replaced by new practices, and this often requires major upheaval.

Major upheaval requires authenticity and integrity on the part of upper managers. Most change efforts do not fail from lack of concepts or from lack of a description of how to do it right. Most change programs fail when upper managers are hoist on their own petard of inauthenticity and lack of integrity. This failure happens because people involved in the situations where managers violate authenticity and integrity sense the lack of resolve, feel the lack of leadership, and despair of the situation. When upper managers speak without authenticity, they stand like the naked emperor: they think they are clothed, but everyone else sees the truth. When upper managers lack integrity they do not “walk the walk”; they only “talk the talk.” People sense the disconnection and become cynical. Management cannot ask others to change without first changing themselves. Implementing the concepts in this book depends on upper management’s resolve to approach the needed changes with authenticity and integrity.

The Need for Project Management

Forces outside the organization are pushing the need for project management. An important shift in the marketplace is that customers who were formerly content with products now demand total solutions to problems. In the past, customers bought an array of products to solve their problems; the functional or bureaucratic organization provided standard products, each of which was a partial solution to problems. Thus, bureaucratic organizations put out products, and consumers needed to piece together components from various companies to solve their problems or create fresh solutions. To provide today’s customers with total solutions, project-based rather than product-based organizations are best. The new organization uses multidisciplinary project teams that move across the organization on the customer’s behalf to provide a total solution. This continuing trend means that project management is both the present and the future of organizational management. Projects also provide the means to offer transformational experiences for ever-demanding customers.

The project management concept is based on cross-functional teams that are assembled to achieve a specific purpose, usually in a specific time and within a limited budget. These teams are temporary; once they achieve their objective, they are disbanded, and team members assume traditional work or are assigned to yet another project. Because project teams cut across traditional functional lines, they are best suited to provide total customer solutions. Typically, one person is in charge of the team: the project manager or project leader.

Project management has taken root in many but not all organizations. New products were often developed by staff in a functional organization. But with increasing pressure to get products to market, special project teams were formed; they also proved useful in developing systems solutions for customers. People in organizations suddenly found themselves working on many projects.

Project management is a trend that will continue to accelerate. During workshops and consulting engagements with numerous participants, we find that more and more people, from administrative assistants up to CEOs, are doing project-based work. Membership and certifications from professional associations such as the Project Management Institute and advanced degrees from universities are increasing.

A shift to projects cannot be accomplished simply by adding projects to department work, because there are substantial differences between department and project work. For one, departments do not foster change; the hallmark of a good department is repeat processes or products, and good department management involves establishing procedures that allow the repeat work to be done as efficiently as possible. This is not conducive to doing something new, because departments support the status quo—in fact, they are the status quo. Projects, in contrast, foster change and thus disturb the status quo.

Furthermore, departments normally are not cross-functional, whereas projects require a cross-functional view of the entire organization because the target of projects is often a system (such as payroll, customer profiles, customer interface, or a set of products) that is itself part of a larger system or at least connected to some other system. For a project to be successful, its effects on all other systems need to be considered. People skills in departments are more often focused on production rather than on developing processes to achieve unique new results. Tales of failures caused by unexpected consequences are legend in any new operation. It takes a total view of the organization to ensure successful projects, and this requires a cross-functional team. This wide view is normally not found in departments.

Also, departments are assumed to last forever, whereas projects have a limited life. Because projects are temporary, they are not seen as the department’s “real work” and so are given low priority and not assigned the best people. This is a recipe for project failure.

Departments are also level conscious. Much of the power and leadership in departments depends on the level in the hierarchy. Projects require multilevel participation. The power should flow to the person who can get the job done, and this may often require that people work for someone below their level. This could be difficult to achieve in departments.

The role of upper management is of paramount importance in developing a project-based organization. Such development involves a lot more than moving lines and boxes on an organization chart, sending a few managers out to training, and telling them to “do project management.” The process of developing a project-based organization mirrors the desired new organization because the process is itself a project. It requires a vision of how the organization will function and what it will achieve. It requires that upper managers act as a team among themselves and with project managers to change the organization. It requires a change in behavior, as an organization is not a chart but rather the sum total of the behavior of the people who work in it. It also requires a plan and the participation of important stakeholders, such as customers.

Organizations have found cross-functional project teams to be very effective for project work. For example, when Chrysler went to a platform team for its cab forward design, it cut the new model development time from three and a half or four years down to only two years. In addition, the number of people necessary went from fifteen hundred to seven hundred. When PECO Energy attempted to refuel nuclear reactors using a departmental approach, it took 120 days. With a cross-functional team approach, PECO set a company, U.S., and world record for refueling time of just under twenty-three days in February 1995 (“Company Sets Industry Standard,” 1996). Refining the team approach, it set another world record in October 1996, completing the refueling in nineteen days and ten hours. PECO officials attribute this achievement to two years of planning, superb coordination, and great teamwork. Examples like this are commonplace when organizations begin to take the project management approach seriously. Clearly the payoff is well worth the effort.

Toward the Project-Based Organization

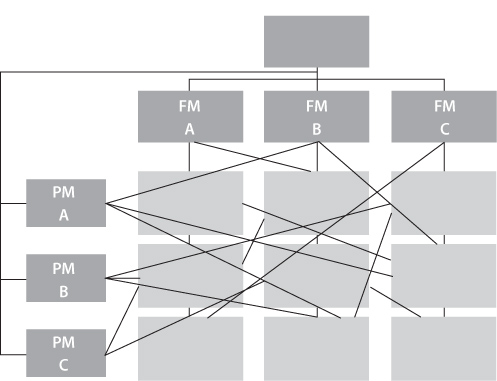

In initial attempts to respond to the need for project management, many organizations attempted to integrate projects into a functional organization by using the matrix approach, in which functional managers (designated as FMs in Figure 1.2) control departments such as engineering and marketing and project managers (PMs) coordinate the work across functions.

But in general, the matrix organization tended to cause more problems than it solved.

The major fault was that it was a marginal change—a mere modification to the old hierarchical organization. This meant that many of upper management’s assumptions were based on the functional organization or mechanistic model. As a result, many of the behaviors that were rewarded by upper management were actually counterproductive to successful projects. Project team members felt that organizational rewards favored departmental work and that working on projects was actually bad for their careers. Many people working in a matrix organization complained of being caught in a web of conflicting orders, conflicting priorities, and reward systems that did not match the stated organizational goals (see Figure 1.3). Effective behavioral change requires a change in the reward system, and this did not occur in many matrix organizations.

FIGURE 1.2 Matrix Organization

The use of a matrix for project management is a classic case of rewarding one behavior while hoping for another—that is, rewarding departmental work while hoping for project work. Although people were told that working for two bosses would be beneficial to their careers, experience proved to them that doing project work decreased their chances for promotion. Because they did not see project work as compatible with their personal interests, the project work suffered. The rewarded behaviors were those the organization wanted to discourage, and the desired behaviors were those that went unrewarded. Such organizational perversity is an example of the type described in Kerr’s classic article, “On the Folly of Rewarding A, While Hoping for B” ([1975] 1995; see Box 1.2).

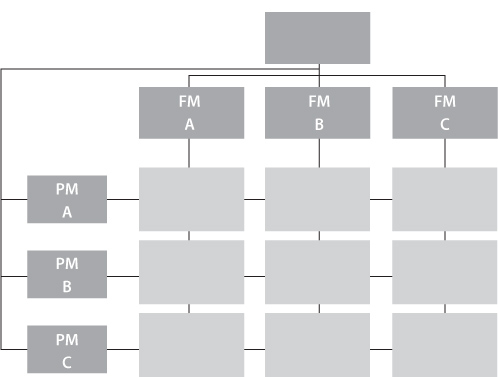

FIGURE 1.3 Caught in a Web

BOX 1.2 Organizational Perversity

Steven Kerr realized that individuals seek to know what activities will be rewarded by the organization and then carry them out, “often to the virtual exclusion of activities not rewarded.” However, he found numerous organizations where the types of behavior rewarded are those that the rewarder is actually trying to discourage, even as the desired behavior is not being rewarded at all. Kerr cites examples such as universities, where “society hopes that professors will not neglect their teaching responsibilities, but rewards them almost entirely for research and publications,” as well as “sports teams [that] hope for teamwork but usually reward based on individual performance” and “business organizations [that] hope for performance but reward attendance.” We have experienced organizations that say they want upper managers to oversee and mentor projects but reward them based on the number of people in their department. They are, in other words, organizationally perverse: their organization members say they want one behavior but reward activity that will ensure that it cannot be accomplished.

Because the matrix approach represented only a marginal change, the typical problems of bureaucracy often appeared. In many cases, the money continued to reside in the departments, with projects having limited budgets. Project members were treated as second-class citizens. In addition, individual positions and promotions continued to reside in the departments, making those groups much more important for long-term career success. Even if projects were given budget authority, conflicts over priorities continued to arise. Rules were then needed to resolve conflicts, and these rules tended to accumulate. Whenever a mistake was made or a conflict noticed, a rule was made to prevent its recurrence. As a result, operational responsibility tended to drift upward, and conflict resolution required top management involvement. Finally, the rules began to guide behavior and became a concern in themselves. People acted with concern for the rules, not with concern for the success of the whole. This is classic bureaucracy in action.

The weakness of bureaucracy brings the tenets of the organic organization into focus. The organic organization is one in which everyone takes responsibility for the success of the whole. When this happens, the basic notion of regulating relations among people by separating them into specific predefined functions is abandoned. The challenge is to create a system where people enter into relations that are determined by problems rather than by structure (see Figure 1.4). Connecting lines show people working together on project teams. I (Englund) can attest to this structure as I had an R&D manager on a systems development team along with individuals and managers from various departments. In essence, people market their services to those projects inside the organization that need them and are capable of paying for those services.

The tenets of such an organization are described in The Post-Bureaucratic Organization (Heckscher and Donnellon, 1994), in which the basic building block is considered to be the team. Consensus on action is reached not by positional power but by influence—the ability to persuade rather than to command. The ability to persuade is based on knowledge of the issues, commitment to shared goals, and proven past effectiveness. Each person in the group understands how his or her performance afects the overall strategy.

Ability to influence is based on trust, and trust is based on interdependence—an understanding that the fortunes of the whole depend on the performance of all participants. The empowered manager assesses the level of trust and agreement that exists with another person (Block, 1991) and plans an approach to that person that leverages the strengths of that relationship.

Highly effective people in this organization can influence without authority by using reciprocity as the basis for influence. People need to learn to exchange “currencies” (Cohen and Bradford, 2017) based on respective needs, leading to win-win situations. Communications need to be explicit and out in the open.

Stand Up for a Dollar Exercise: This is an exercise I (Graham) designed to help prospective project managers really understand the need for management integrity, the glue that holds the puzzle together. Standing in front of a project management class, I hold up a dollar and state that I will give that dollar to the first person that I see stand up. Usually the participants are stunned, and no one moves. However, after about a minute, someone will stand up and I give them the dollar.

I then ask the other participants why they do not have that dollar. The usual response is that they did not believe that I was really going to do it. I respond by saying, “I told you I was going to do it.” The usual response to that statement is that they don’t know me, so they didn’t trust me.

I then protest, saying that “many people call me Honest Bob,” and they usually respond that it makes no difference what others say; they won’t believe me until they get to know me. At that point I start to take another dollar out of my wallet and people start to stand up before I say anything.

When I ask the group about the difference in behavior between the first and second dollar, they say that they feel they know me better because they saw me give away the dollar the first time. The lessons for new project managers and upper managers alike are clear: your team members and others don’t know you, so they don’t really trust you. Don’t take it personally. Only after you do what you say you are going to do will they begin to develop trust. That trust is all important for good project management. It is the glue that holds teams together.

I (Englund) encountered similar behavior during consulting engagements. A common theme arising from interviewing a cross section of colleagues is lack of trust. Probing further, the cause is not usually because of previous bad experiences; rather, it is a default response of not knowing others is to not trust them. A simple antidote is getting all colleagues together, to develop personal relationships that engender trust. Suggest a new default of trusting others, until encounters prove otherwise.

Structure of a Project-Based Organization

A strong emphasis on interdependence and strategy leads to a strong emphasis on organizational mission. In order to link individual contributions to the mission, there is increased emphasis on information about the organizational strategy and an attempt to clarify the relationship between individual jobs and the mission. This calls for a new type of information system where information linking individuals to the strategic plan is readily available.

Guidelines for action take the form of principles rather than rules. Principles are based on the reasons that certain behaviors contribute to the accomplishment of strategy. One important principle is a relatively open system of peer evaluation, so that people get a relatively detailed view of each other’s strengths and weaknesses. This calls for a change in the evaluations and reward system. In addition, this type of organization has no boundaries. There is far more tolerance for outsiders coming in and insiders going out. The boundary between the organization and its customers blurs, and the boundaries between levels and departments within the organization disappear. In addition, the postbureaucratic organization eliminates the idea of permanence, where decisions are final. The emphasis is now on decision processes.

As many project teams already embrace these structural elements, it stands to reason that organizations will find it easier and beneficial to become more project based and customer oriented. Since customers want to buy solutions, not standard products, the organizational unit that can respond to this market is the customer-oriented project team. The team works to understand the customer’s problems and what the team should achieve. With this understanding, the team can develop new solutions, perhaps ones that customers or end users had not even imagined. This requires a changed relationship between the company and the customer: the customer becomes a vital part of the team.

Segmentation studies of top performing companies identified three innovation models for strategic alignment that is crucial to project-based organizations: need seekers, market readers, and technology drivers (Jaruzelski, Chwalik, and Goehle, 2018, pp. 57–69). Making up 34 percent of respondents, need seeker “companies engage customers directly to generate new ideas, then develop original products and services and get them to market first.” Market readers, which make up 23 percent, are fast followers that “typically generate ideas by closely monitoring their markets, customers, and competitors, focusing largely on creating value through incremental innovations to current products.” Technology drivers, 44 percent of respondents, “depend heavily on internal technological expertise to develop new products and services, driving both breakthrough innovation and incremental change to meet known and unknown needs of customers via new technology.”

Furthermore, “need seekers are far better than market readers and technology drivers at turning their corporate culture to their advantage.” Apple, which has long been identified as a need seeker, has placed innovation into the company’s cultural DNA. It hires people who can collaborate cross-functionally.

Customer-driven teams abandon the level-consciousness about relative job positions prevalent in many functional organizations. Project leaders are appointed because of their expertise in running projects, not because they have attained a particular level in the organization. Because the ability to influence is not based on position, level-consciousness decreases. In addition, as there are fewer levels, position becomes less important. A team member may be one or two levels above the project manager on the organization chart but still report to the project manager for that project (as in Figure 1.4). Team members no longer think of themselves as members of a particular function but as members of a team that is doing something for the good of the entire organization. Several customers may become members of the team, as was the case on the Boeing 777 airliner project (King, 1992). Many team members may be from outside the organization, doing work on contract for that particular project. The project manager thus assembles the project team based on what is best for the project, not on which people the organization can spare.

Becton-Dickinson, an organization that embodied this trend, provides innovative technology and advanced solutions in flow cytometry systems (Stoy, 1996). In designing an organization to be more responsive to the needs of development programs, this company found that embedded functional management was delaying the cycle time. To help reduce cycle time, it eliminated functional managers and their departments. The important tasks of functional managers were put into focused groups, and a project management office was established to develop direction for project management in the new organization.

Increasingly, organizations will consist of a smaller group of full-time employees and a large contractual fringe of individual contractors or strategic alliances that provide goods or services for given projects. In other words, the customer-based team properly comprises a small core of employees plus relationships with outside experts who work contractually for all or part of a project. Internal market organizations are based on areas of expertise and have profit and loss responsibility. Each area provides services to other areas for a fee. Rather than having their performance measured by how well they stick to a budget, these areas are measured according to how well they complete an internal project that helps the rest of the organization achieve its mission. In this way, everyone knows how their actions affect both profitability and the attainment of a mission that is stated in a strategic plan.

Moving to a project-based organization presents unique challenges to upper managers, as outlined by Wilson and others (1994):

• The leader has little or no “position power.” The position power inherent in functional organizations has to change as the project-based organization is introduced. The team leader has little direct control over the career paths of team members. Instead, team members require an independent career path over which they themselves have control and to which the project work can contribute. Developing such a scheme is similar to the development of an individual retirement account, where the employer makes contributions but the individual has control of the fund. This type of scheme has been used in universities for years; it allows professors to move easily from place to place, taking their retirement account with them. Organizations need to make it easy for team members to move from project to project, taking their career path progress with them.

Asked by a gathering of project managers whether the project management skill set was transferable to other functions, former HP CEO Lew Platt (1994) replied, “I think if you learn the skills of project management that you can manage a project in manufacturing, or a project in IT, or a project in marketing just as easily as you can manage a project in development. The issues are different, but I think the basic skills are pretty much the same.… In these times, it is quite important that you actually do think about moving around from one function to another as a way of getting a fresh set of experiences, reigniting your interest in the job.… It’s a tremendous growth experience.”

Upper managers need to develop project managers and project management so that the project managers can lead based on influence rather than positional authority. Developing project managers and career paths is discussed in Chapter Seven.

• Conflicts arise over team member time and resource requirements. Thus, upper managers need to have a good plan and work out priorities. Alternatively, internal market pricing may be used to allocate scarce resources—individuals or organizations pay with internal charge accounts, sometimes called location code dollars, for services they find valuable. Value-based pricing mechanisms are a feature of internal market-based organizations. Ideas for allocating resources are covered in Chapter Two.

• Organizational boundaries are unclear. Project management often requires quantum leaps in the level of cooperation among organizational units. If people see evidence that cooperation is not valued, achieving cooperation is almost impossible. The alternatives to cooperation are turf wars and as-needed appeals to higher authorities, neither of which is beneficial in the long run. Upper management needs to create a structure where cooperation is rewarded. This is discussed in Chapters Two and Five.

• Time and organizational pressures abound. Upper management must be ready to support best practices that allow reduction in cycle time. This includes developing a core team system, developing project goal statements, allowing time for project planning, not interfering with project operations, facilitating communication with customers, and supplying necessary resources. In addition, an adequate project time frame needs to be negotiated so that the team has a chance for a win. These topics are covered in more detail in Chapters Three and Four.

• Team members do not know one another. Effective project teams require unprecedented levels of trust and openness. The climate of trust and openness starts at the top. If upper managers are not trustworthy, truthful, and open with each other, there is little chance that project team members will be so with one another. Trust and openness are the antithesis of most bureaucratic organizations. Upper managers coming from a less trusting organization may have difficulty developing high levels of trust.

• Team members are independent and self-motivated. Because team members may not even work for the organization, project managers need to develop influence skills, and upper managers need to support training and development of negotiating skills.

All these challenges require that upper managers work together to develop a process aimed at encouraging new types of behavior. Members of the organization look to the upper managers for guidance in both strategy and behavior. If there is a lack of integrity between what is said and what is done, skepticism rises and morale falls. How can upper managers expect good teamwork when they fight among themselves? Organizational change requires not just a concept of a new organization but the resolve to create it. If upper managers expect team members to change their behavior, they should be ready to change their own behavior as well. Sending people to project manager training is not enough. The shift to a project-based organization requires a concerted effort from all upper managers, as well as training for themselves.

A Model of Organizational and Behavioral Change

Any group of people may be said to have a culture: a set of beliefs, values, norms, and practices that help the group solve its problems. Business organizations are groups of people and thus have a culture too; therefore, a revitalization model can be used to describe the phases of change in organizational cultures. For changes in organizational culture to occur, behavioral changes in the people who make up the culture need to occur.

The steps to achieve actual change in behavior are difficult indeed. Few believe in the benefits of change until they actually experience them. Change agents often feel like the person described by Plato (see Box 1.3), particularly when their visions of the future provoke ridicule. When new ideas provoke ridicule in an organization, it usually means that the people in it are not ready for change because they do not yet see the need. If upper managers start a change process before they really believe change is necessary, others will sense this lack of authenticity and the process will fail. A change process is effective when the change leaders believe it is necessary and show the way to others. The revitalization process acknowledges this fact and describes the stages an organization goes through until the majority of its members are ready for change.

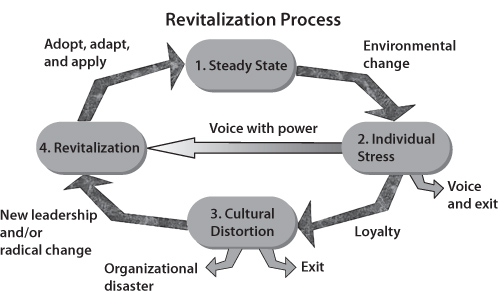

The revitalization process model described by Wallace (1970) considers the time and processes necessary to change behavior. He uses this model to describe a society moving through a series of temporally overlapping but functionally distinct phases of change. The stages of the revitalization process are shown in Figure 1.5. Basically, successful organizations develop procedures that allow them to achieve a steady state such that the organizational system handles any problems that arise. But as the environment changes, continued use of old procedures causes people to enter a period of individual stress. If this is allowed to continue, the organization falls into a period of cultural distortion, where the procedures cause many problems. However, enlightened upper managers can bypass that state and go directly to a period of revitalization, in which new procedures are adopted to match the problems in the revised environment.

Feedback from previous readers describes how this model provides increased understanding for them about what is happening in their organizations. Sometimes a tactic is to be patient during the stress and distortion stages while at the same time preparing for revitalization; this includes studying best practices, proposing new operating modes, and developing an increased set of skills (Englund and Bucero, 2019a). A good way to depict the model in action is to use historical references.

BOX 1.3 Response to Change Agents

According to Plato’s Republic, “Human beings are like prisoners chained to the wall of a dark subterranean cave, where they can never turn around to see the light of a fire that is higher up and at a distance behind them. When objects outside the cave pass in front of the light, the prisoners mistake as real what are really shadows created on the wall. Only one who is freed from his chains and leaves the cave to enter the real world beyond can glimpse true reality.… Once he habituates himself to the light and comes to recognize the true cause of things, he would hold precious the clarity of this new understanding.… Were he be required to return to the cave and contend with the others in their usual activity of ‘understanding’ the shadows, he would likely only provoke their ridicule and be unable to persuade them that what they were perceiving was only a dim reflection of reality” (Tarnus, 1991, p. 42).

THE STEADY STATE

Every organization begins with a set of problems that need to be solved in order for the organization to carry on its business. (The case of early AT&T is a good example; see Box 1.4.) Successful organizations develop a culture—a set of beliefs, values, norms, and practices—that helps the members of the organization solve these problems. This culture is embodied in a set of organizational rules that are passed on from one generation to the next. Application of these rules keeps the organization in a state of equilibrium. Each year looks much like the last, as the organization produces similar products through repeatable processes. The members of the organization become more and more efficient at applying the rules, and the organization thrives. This is the steady state, which we could equate to the mechanistic or functional model of organizations.

To keep an organization in the steady state, a control system is developed. Whenever outside disturbances threaten the equilibrium of the organization, the control system detects and interprets them and sets in motion practices that counteract them.

Control systems are both internal and external. The external control system attempts to regulate the environment in a way favorable to the organization, such as by gaining patents, monopolies, or other favorable government rulings. The internal control system regulates members’ behavior and works to eliminate any threat to the smooth functioning of the organization. Organizations in the steady state are characterized by large and onerous control systems that, as we shall see, become their undoing.

During the steady state, the organization is usually successful and often able to affect its environment more than the environment is able to affect the organization. This is often due to some patent, monopoly, or new process the organization has developed that is not yet general knowledge. When this is so, there is little time pressure on projects; the control system acts to fend off the need for change. As a result, project management is not really necessary. Projects wend their way through the bureaucracy in due course.

Functional organizations were a necessary step in the evolution of organization design. Consider the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, a forerunner of today’s AT&T, which was established on February 28, 1885. It was formed to operate long-distance telephone lines to interconnect local exchange areas of the Bell companies. Although it must have seemed incomprehensible in 1885, the plan was to extend those lines to connect “each and every city, town and place in the State of New York with one or more points in each and every other city, town or place in said state, and each and every other of the United States, and in Canada and Mexico … and by cable and other appropriate means with the rest of the known world” (Shooshan, 1984, p. 9).

Such a lofty goal required massive generation of and attention to standard procedures. Without each and every city, town, and place following the same procedures, there is no way the AT&T network could have been completed. The procedures helped solve problems. After all, there was no way to call to discuss and fix connection problems until the phone was actually connected. So, bureaucracy was created by necessity, allowing the next generation of organizations to emerge from it.

For example, AT&T reached its steady state in the period 1934–1960 (Graham, 1985). By 1934, the Bell system had operating companies in most major American cities, and AT&T could proceed to tie them together and provide the dream of universal service. To provide this service, AT&T was given a telephone monopoly in the United States. Given the lack of competition, AT&T developed a steady, stable, predictable, and military-like culture that allowed the efficient realization of the goal. The antitrust cases brought against AT&T during this period were defeated.

THE PERIOD OF INCREASED INDIVIDUAL STRESS

Over time, the environment of an organization changes such that the existing culture is no longer appropriate for the problems it faces. When, for example, customers begin to demand new and different products and solutions, the assumptions on which the organizational culture was built become increasingly invalid. Following old procedures at such times begins to cause problems rather than solve them. Some individuals in the organization begin to realize that major changes are necessary, but they often go unheeded as others continue to find success using the old ways. During this phase, the organization continues to be successful—it may even experience its most successful period—so it is not surprising that many members of the firm do not see the need for change.

Problems get exacerbated because those who see the need for change and sound the alarm are often forced out of the organization (we have seen cartoons depicting a director addressing a board saying, “Those who said I should retire … are not here anymore”). In the process of exit, voice, and loyalty described by Hirschman (1970), people who see the need for change often leave the firm (exit) and join other organizations where the change has already been made or is being implemented—firms that are already in their period of revitalization.

An alternative to exiting is to voice strong opinions about the needed changes. This is often followed by exiting; as other members of the firm do not see the need for change, the advocate of it is likely to be accused of not being a team player. If the individual still does not want to exit, the final alternative is loyalty—succumbing to pressure and going along with the others. No change takes place; the fate of potential change agents during the period of increased individual stress is that they leave the organization or join the majority.