Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Culture Crossing

Discover the Key to Making Successful Connections in the New Global Era

Michael Landers (Author)

Publication date: 01/09/2017

People, money, and information are flowing faster than ever across international borders, putting us all just one step away from a culture crash—that moment when you unintentionally confuse, frustrate, or offend someone from another culture. Are you struggling with trying to learn the customs, nuances, and hot buttons of every culture you might come into contact with? Michael Landers guides you toward a better solution: becoming aware of your own cultural “baggage.” You'll learn to sidestep the knee-jerk reactions that can get you into trouble and develop the agility to adjust your behaviors and expectations as needed. Through a mix of entertaining and instructive stories, valuable insights, and eye-opening self-assessments, Culture Crossing offers an essential primer for improving all your interactions with people from any background.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

People, money, and information are flowing faster than ever across international borders, putting us all just one step away from a culture crash—that moment when you unintentionally confuse, frustrate, or offend someone from another culture. Are you struggling with trying to learn the customs, nuances, and hot buttons of every culture you might come into contact with? Michael Landers guides you toward a better solution: becoming aware of your own cultural “baggage.” You'll learn to sidestep the knee-jerk reactions that can get you into trouble and develop the agility to adjust your behaviors and expectations as needed. Through a mix of entertaining and instructive stories, valuable insights, and eye-opening self-assessments, Culture Crossing offers an essential primer for improving all your interactions with people from any background.

Michael Landers is the founder and president of Culture Crossing, Inc., a global consulting company dedicated to finding innovative solutions for those working in global contexts. Although American, Landers was raised throughout Latin America and speaks Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese and is proficient in Japanese and Italian. Culture Crossing s clients include Apple, Google, Samsung, HSBC, SAP, Novartis, Fiat Worldwide, Isuzu Motors of Japan, Kaiser Permanente, CalAtlantic Homes, and Mead Johnson.

—Brian Tracy, author of How the Best Leaders Lead and Eat That Frog!

“Drawing upon his own extensive international experience, Michael has created an indispensable tool for anyone who interacts with people from other cultures. (And who among us doesn't?)”

—Luciana Duarte, Global Head of Employee Communications, Engagement, and Culture, HP Inc.

“I wish I had this book sooner! Between working abroad in India and starting a company in New York City, I've found myself in so many situations where I didn't know what the cultural norm was. I can't wait to apply the lessons I've learned from Culture Crossing to situations I know I'll find myself in in the future.”

—Liz Wessel, cofounder and CEO, WayUp

“Understanding culture is the key to creating and maintaining successful relationships in this increasingly global world. This book is a must-read for those just entering the workforce to the leaders of top companies.”

—Alex Churchill, Executive Chairman, VonChurch, and CEO, Gamesmith

“Michael combines a rare and deep understanding of global cultural issues with humor to create awareness on one of the most important topics of our era. His stories and teachings have been invaluable for us at SAP Academy, as we have trained hundreds of millennials from over fifty countries in our global training facility. If you serve in any organization or role in which you work with people from different cultures, run, don't walk, to read this book.”

—Rae Kyriazis, Global Vice President, SAP

“The most profound reality we face as marketers is the multicultural fractionalization of our marketplace. We are perplexed by this, so we continue to talk in our own voice rather than learning how to listen to these diverse voices with an empathy that is agile and truly customer-centric. Michael Landers has changed the way our people think and act with his method and teaching.”

—Bill McDonough, Senior Vice President and Chief Marketing Office, M/I Homes

ONE

Cultural Awakenings

How culture shapes our thoughts and behaviors

When you ask a five-year-old kid from the United States what a dog says, he or she will probably say “woof-woof” or “bowwow.” Ask a kid living in Japan, and you’re likely to get a “wan-wan.” Try it in Iran, and you’ll hear “hauv-hauv.” In Laos they say “voon-voon.” It’s “gong-gong” in Indonesia and “mung-mung” in Korea.

Besides being a fun bit of knowledge to share at a dinner party, animal sounds are a good example of how people from different cultures are programmed from an early age to interpret the same experiences in different ways. It also underscores how culturally specific perceptions can get deeply lodged in our brains. Imagine if you suddenly had to convince yourself that your dog was saying “voon-voon.” Unless you are from Laos, it would probably take a while.

Here’s another example: think about how you indicate yes and no without using words. For most people in the United States, the answer is simple: nodding your head up and down means “yes,” and turning your head left and right means “no.” In Bulgaria, however, nodding your head up and down means “no,” and turning your head left and right means “yes”!

Just for fun, here’s a challenge for you, to test your own programming: try answering the following two questions with a nonverbal “yes” or “no,” but do it the Bulgarian way, turning your head side to side for “yes,” and up and down for “no.”

Do you want to win the lottery?

Would you pay $100 for a hamburger?

For most people, answering these questions is probably more challenging than you expected it to be. After hearing, seeing, believing, or doing anything a particular way throughout your whole life, it can be extremely difficult to change the way you act, react, or perceive someone else’s behaviors. It’s all a result of programming, some of which is biologically hardwired and some of which is based on our experiences. Your cultural programming comprises various combinations of values, perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, and behaviors—and it plays a large role in shaping our identities, providing us with instructions for how to navigate our lives.

In our earliest years we’re taught things like language, manners, societal do’s and don’ts, punishable behaviors, and what sound a dog makes. As our cultural programming continues to accrue and be reinforced over our lifetimes, it manifests in the way we make decisions, problem solve, perceive time, build trust, communicate, buy and sell, and even how we die.

Some of our cultural programming has been handed down to us by ancestors who lived thousands of years ago, but our programming is also continuously rewritten by contemporary communities, seeking to make sense of outdated programming in a modern context. We as individuals have the choice to adapt our personal programming to new scenarios and surroundings, or not. It’s the technological equivalent of updating your operating system. If you don’t perform the update, your functionality may be compromised.

Despite the profound ways in which culture influences our personas, most of us are barely aware of it—that is, until we encounter people whose cultural programming is different from ours. Our minds—our personal operating systems—may freeze up and crash just as our electronic devices do. Instead of manifesting as a frozen screen, it causes us to feel uncomfortable, perplexed, and frustrated. We may shut down, explode with emotion, or simply give up and walk away—thereby missing out on opportunities to build positive relations and achieve success at work and in other aspects of our lives. I call these kinds of encounters culture crashes.

When culture crashes happen, it is often a result of unconscious incompetence. More simply put: “You don’t know what you don’t know.” Acknowledging that you are in the dark is actually the first step to increasing your self-awareness and avoiding the kind of “crash” just described. It means you are ready to open your mind to things you may never have considered before.

Some of our behaviors are modeled on those we have seen or heard, like how to make animal noises or indicate yes or no. But there are hundreds, if not thousands of other more nuanced behaviors whose cultural origins are less apparent. These are things like how close you usually stand to a friend or colleague while talking, how promptly you show up for a party or business function, or whether and when you look someone in the eye.

While some of these habits can be chalked up to individual personality or experience, many of them are rooted in culture. For example, when I ask people from the United States what makes someone seem trustworthy to them, one of the most common answers is: “Someone who looks me directly in the eye.” So when someone doesn’t look them in the eye, they immediately begin to question whether or not this person is trustworthy.

In many Western cultures, direct eye contact is viewed as a sign of respect and expected between people of all ages and genders. But in parts of Thailand, Oman, and Japan, direct eye contact is often construed as a sign of disrespect, especially between genders and people of different ages.

I can clearly remember my first experience with eye contact confusion when I moved to Japan to teach English in my early twenties. I was struck by how practically none of my students would look me in the eye, even those who were significantly older than I was. In the United States, this would have been construed as a sign of disrespect, but in Japan, avoiding eye contact with your teachers is a show of deference. I tried to train my students to look me in the eye when speaking English, and they eventually got the hang of it. Meanwhile, I was busy trying to retrain myself to avoid the eyes of my Japanese martial arts master. It was much more challenging than I anticipated.

The way we greet others is also something we are culturally programmed to do at a very young age, but the way in which we perform these greetings is continually refined over time as we learn about the more subtle implications. Consider all of the nuances of a gesture as seemingly simple as a handshake. The strength and length of your grasp, the hand you use, and what you do with your eyes while you shake all have certain implications. In the United States, a firm handshake generally signifies a sense of confidence—a positive attribute. Conversely, offering a limp, “dead fish” handshake can cause the person on the receiving end of the shake to feel uncomfortable and question the confidence, authenticity, and professionalism of the other person. If the handshake is firm but lingers too long and turns into a hand-hold, people may feel uncomfortable or threatened by behavior interpreted as pushy, and they may start to question the person’s motives.

Meanwhile, in parts of the Middle East and Africa, the same lingering handshake often signifies respect, admiration, or commitment to the personal or business relationship. If someone tries to pull away too quickly, it could be viewed as a sign of disrespect or lack of trust and dedication.

Former President George W. Bush was well coached in 2005 when he strolled through the garden of his Crawford, Texas, compound holding hands with Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, in an effort to improve relations and lower oil prices.1 But photos and videos of them holding hands struck a nerve with U.S. citizens. It became fodder for news reporters and late night talk show hosts, and “man on the street” interviews in U.S. cities revealed how people were agitated by the handholding and struggled to make sense of its implications.2

Now consider how someone might not be aware of any or all of these nuances if he or she was raised in a culture where handshaking is not a typical greeting. If you had grown up in a place like Korea or Japan you probably would have been taught to bow as a greeting, and learned to do it to the correct depth, depending on the person or the context. In Thailand you might be assessed for the position of your wai, a common greeting that entails holding your palms pressed together and held close to your chest while slowly lowering your head. In places like Italy, Lebanon, and Brazil, you would learn to dole out the appropriate number of kisses and exactly where and how firmly to plant them on someone’s cheek.

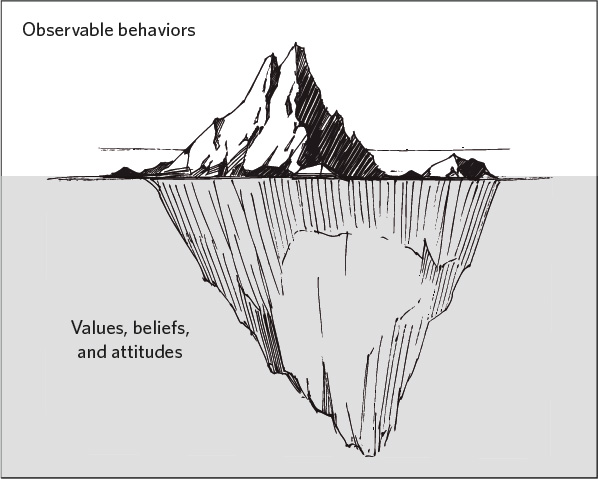

The nuances of all these gestures are equally as subtle as those for the U.S. handshake. Of course, behaviors like greetings and eye contact are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to differences in our cultural conditioning. Look below the surface, and we start to uncover some of the underlying reasons why we do what we do, and we begin to discover the key to increasing our cross-cultural awareness.

Cultural Icebergs

Boarding a public bus in Colombo, Sri Lanka, can feel at times like trying to be the first one through the doors of Walmart on Black Friday. Or at least that’s how it was described to me by a friend who traveled to this tear-shaped island off the coast of southern India a few years ago.

Based on her upbringing in the United States, she has certain expectations about how to board buses—or trains or planes, for that matter. She doesn’t always expect people to stand in a perfect line. She’s jammed herself into crowded New York City subway cars countless times. But she does assume people will get on a bus in some sort of orderly and courteous fashion. Here in Colombo, however, as they opened the doors at her downtown stop, it was as if a stampede was bearing down on her. Standing in the midst of a crush of bodies trying to squeeze through the narrow doorway was not only startling and illogical to her, but sort of scary too. But mostly she interpreted this behavior as rudeness.

Two things happened during this experience. First, she observed the behavior of the people jamming themselves onto the bus. Second, she interpreted this experience based on how she’s been boarding buses her entire life. Her interpretations caused her to feel annoyed, uncomfortable, and disrespected. But what if she didn’t have those expectations? What if she had been raised in a culture where everybody boarded a bus this way?

How people stand in line is one of those culturally influenced behaviors that are easy to observe, although we may not even realize that culture is at work behind the scenes. The list of easy-to-spot behaviors includes what people eat, how they dress, the language they speak, the tone of voice they use, gestures, and so on. What’s more difficult to observe is the why behind these behaviors. And knowing the why—or at least being open to the idea that the whys can vary significantly—is the first step to improving your cross-cultural agility.

The most obvious answer to the question of why we do what we do is this: because that’s what everyone else does. In places like the United States, Great Britain, or Germany, you quickly learn to line up for the bus, and that cutting the line isn’t cool. In many parts of China or India, on the other hand, lining up is not generally expected, and people learn quickly that if they don’t forge ahead, they may never get on the bus.

But the reason why entire groups of people tend to board buses in different ways has to do with the values, beliefs, and attitudes of each culture. In cultures where order and efficiency are highly valued in all aspects of life, these virtues dictate the way people queue up. In other cultures, order is generally viewed as a behavior warranted only in certain situations, not in all facets of life. Another cultural factor that can influence how people line up relates to varying perceptions of space and time—a fascinating subject that we’ll explore in chapter five.

By now you’ve gotten the picture that culture influences us in countless ways, leaving its mark on everything from how we view time and create priorities to how we cultivate relationships and grow old. The building blocks of our cultural programming are values, beliefs, and attitudes—invisible elements that subconsciously drive many of our behaviors.

Invisible is the key word here.

You most likely have seen the iceberg model (Figure 1.1) before in learning and development contexts. I use it here because it can help you wrap your brain around these invisible aspects of your cultural programming.

Figure 1.1: The iceberg

We spend our lives reacting to what we observe—what’s above the proverbial waterline. We hear what people say, see what they do, and interpret the nuances of all of this based on our assumptions and prior experiences.

But what if the values, beliefs, and attitudes that lie hidden deep below the waterline are different from our own? Consider that those unseen differences could change the meaning and intent of what someone is saying or doing. What would the implications be?

This is what happened to my friend in Sri Lanka. Her deep-rooted social conditioning caused her to subconsciously assume that everyone else valued public order in the same way that she did. As a result, she interpreted the bus boarding process as chaotic, rude, and disrespectful.

Our minds are hardwired to jump to the conclusion that others’ values and beliefs—and the meaning behind their behaviors—are the same as our own. The good news is that it’s possible to override our brain’s hardwiring and build a new, more culturally responsive navigation system. With practice and knowledge, we can rein in our automatic responses, open our minds to different interpretations of what people say and do, and adjust our reactions accordingly.

As an example, at the Sri Lankan bus stop my friend could have done a few things differently. First, before jumping to conclusions, she could have paused to recognize how she was feeling. Then she could have cleared out some mental space to open her mind and assess the situation, and observe that everyone else was acting the same way. Having done that, it would have been easier for her to adjust her reflexive reaction. She still would have felt jostled and uncomfortable, but it probably wouldn’t have made her feel angry or disrespected, or caused her to start developing negative stereotypes about people from this culture. She also could have used the same assessment method if she had been boarding the bus in a U.S. city and someone from another culture shoved her in order to get on more quickly. Instead of immediately getting upset and lashing out, she could have considered that the person had not yet adapted their own cultural programming to mesh with way people board buses in the United States.

In a similar vein, armed with your new awareness about the nuances of greetings across cultures, you could hit the pause button during a handshake and recognize that any differences from the handshake you expected could be making you jump to false conclusions about the other person. Your heightened awareness might lead you to adjust your own greeting style so you don’t make the wrong impression or send an unintended message.

These are just a few examples of the countless scenarios in which improved cultural awareness and adaptability can help you connect with others—as opposed to crashing. In today’s globalized communities, workplaces, and markets, raising your level of awareness and adaptability is essential to making successful culture crossings.

Some people might question the need for this kind of cultural dexterity in light of an emerging “global culture”—a sociological phenomenon that suggests cultures are becoming more alike. The rise of this global culture is a result of economic and technological changes that are accelerating and expanding the flow of people and ideas across national boundaries. The ever-broadening dispersal of media, arts, and consumer products is facilitating this diffusion and assimilation of cultural values, preferences, and protocols, changing the way that we behave and think. Global culture is further fostered through advances in communication technology that make it seem easier than ever to communicate and “connect” with people from diverse nationalities. But don’t be fooled. There are still plenty of nuances that can and do get lost in translation, largely because it is so difficult to override your earliest and deepest programming. Few if any behaviors are truly universal;3 no emoji expression will ever be completely fail-safe in its implications.

So how do you retrain your brain to deftly navigate a wide variety of cross-cultural interactions? For starters, you have some unpacking to do.

Unpacking Your Cultural Baggage

Whatever my clients’ goals are—whether they are relocating to another country, trying to sell goods and services to recent immigrants on their home turf, or trying to defuse tension in a multicultural office—the first step is always the same: they have to get familiar with the many ways that their own cultural programming influences their behaviors.

Another useful way to wrap your brain around your own programming is to think of it as baggage—cultural baggage. Much like emotional baggage, cultural baggage is something we unwittingly tote around with us at all times, never knowing when or how it may influence our behaviors.

When we unzip our cultural baggage we can see at a glance those observable behaviors that lie at the top, but not the underlying ideologies that are stuffed deep within or packed away in hidden compartments.

You can start taking inventory of those items in the deepest recesses of your cultural baggage by asking yourself this question: What values truly shape my perceptions, actions, and reactions?

For most of us, it’s not an easy question to answer. We often define ourselves by work and lifestyle choices (sales guy, creative type, vegetarian) or by things that we have a passion for (nature, a sports team, food). But we don’t spend as much time pondering those core values and beliefs that affect so many of our behaviors—things like individuality, formality, and perceptions of time—largely because in the context of a single culture, it’s generally safe to take many of those ideologies for granted. While you may have vast differences of opinion around hot-button political issues, when it comes to certain values, beliefs, and corresponding behaviors, you may find that you are surprisingly in synch with most other people from your culture.

But it can be challenging to identify those core philosophies that unify our own cultures, never mind other cultures. Fortunately, we have at our disposal a good set of investigative tools to jump-start our investigation. We call them proverbs.

Squeaky Wheels and Rolling Stones

One of my favorite parts of delivering cultural training workshops is when I ask people to share a few proverbs from their country or region.

“Hang in there like a hair in a biscuit,” was one of the funnier sayings I picked up last year while speaking to a group in Georgia. If you’ve ever tried to pull a stray hair out of a baked good, you know that this saying is all about tenacity. Although not a quintessential U.S. proverb, this saying clearly speaks to the way that people in the United States value perseverance in many facets of life. Even if someone is unsuccessful—or their efforts are futile—that person is often applauded simply for sticking with it.

The proverbs range from grave to hilarious, but many of them are very telling when it comes to revealing unseen ideologies that drive behaviors in a particular culture. Although some proverbs may be more aspirational than they are actually put into practice, they still offer a useful platform for a first foray into the deep recesses of your cultural baggage.

Consider some other, more classic U.S. proverbs and the messages they send, followed by contrasting proverbs from other cultures.

The squeaky wheel gets the grease. (United States)

From a very early age, most people from the United States are urged to speak up and be heard. Nobody should be silenced. If you don’t like your food, tell the chef. If you are being treated unfairly, let someone know. If you don’t interrupt and speak up at a meeting, people may think that you didn’t add any value.

The proverb “The squeaky wheel gets the grease” is a reflection of the high value that people in the United States place on their constitutional right to openly express themselves and assert their individuality. This freedom was, of course, one of the reasons the first colonists set out for North America.

The duck that quacks the loudest gets shot. (China)

In some countries, asserting your individuality is not a driving value. In cultures like Japan, Qatar, and India, group harmony tends to be valued over individuality (something we’ll delve into in chapter two). In these cultures, group harmony should not be sacrificed in the name of individual merit or airing differences; hence the Chinese proverb “The duck that quacks the loudest gets shot.”

You may have also heard the Japanese proverb “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down,” which reflects the same sentiment. While some cultures might interpret this as conformist or oppressive ideology, residents of Japan or China tend to view this as the key to a harmonious community.

If we don’t acknowledge or abide by the values illuminated by these proverbs when interacting with people from these cultures, it can become a major obstacle to achieving our goals. When I first began my career in Japan, I attended weekly meetings where the mostly Japanese staff would discuss current issues and goals. One of my responsibilities at this company was marketing, and so I would repeatedly volunteer ideas at these meetings about how the company could reach more customers.

My ideas were always met with head nods in agreement and verbal approvals such as, “Good idea, Michael.” But nothing ever happened.

Some six months later I shared my story with a Canadian friend who had been living in Japan for many years, and I discovered that I had been going about it all wrong. He explained that I was supposed to mention my ideas in private to a Japanese peer. Then, if my peer felt the ideas had merit, he or she would share them privately with a more senior peer, who would do the same until it was shared with the manager. All of this would be done in private, behind the scenes.

I decided to give it a try and was shocked when the manager came into the next staff meeting and announced a new marketing plan for the next sales cycle. They were my ideas, presented without any attribution to me. And when the ideas worked and sales increased, there was no reward for me; it was a team win, and that’s all that mattered.

God helps those who help themselves. (United States)

People from the United States tend to believe that they are in control of their destiny, and that they can achieve anything to which they set their minds. If you don’t like something, you can change it; whether it is your job, your spouse, your nose, or even the natural environment. The proverb “God helps those who help themselves” underscores this notion—as does the expression “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

Insha Allah or God willing. (Arab nations)

On the other end of the spectrum are cultures that believe things happen because of the will of God, the universe, or some other higher presence, as opposed to their own will. The expression “Insha Allah,” translated as “God willing,” reflects a belief held widely in Arab countries that our destinies are not in our own hands. The Spanish word ojala, which means “hopefully,” is actually derived from the Arabic insha Allah.

That’s not to say that people from Arab countries leave everything up to the will of a more divine power, or that many people in the United States don’t believe God’s will plays a very important role in determining their future. But there is a tendency within each of these cultures to subscribe to the underlying meaning of the expressions. In other words, some cultures believe that people are mostly in control of the outcomes of our day-to-day actions and decisions, while other cultures continually pay homage to a greater power believed to have a hand in the results of almost everything people do.

When you pose a question to someone from Saudi Arabia such as “So we’ll see you tomorrow at the party?” he or she might nod and respond by saying “Insha Allah” (God willing). The same expression is used for events that most Westerners would assume require a more definitive answer, such as “Will the supermarket open at 10:00 a.m.?” or “Will you be at the office for the meeting with the new clients at 9:00 tomorrow?” No matter the degree of importance, the answer is often “Insha Allah,” suggesting a certain level of acceptance that we are not really the masters of our own fate.

You can imagine the pitfalls that await when people with differing perspectives related to who’s in control, interact. I’ve heard many stories from frustrated real estate sellers in the United States about their fruitless attempts to convey a sense of urgency to encourage a sale. “If you don’t buy now, prices will go up,” or “This one perfect house will be gone if you don’t jump on it” are often successfully used to motivate people from the United States and others to expedite a purchase. But for people who are more of the “God willing” mindset, their attitude is that whether they get the house or not may have little to do with how fast they act. Their thinking may be more along the lines of “It will happen if it’s meant to happen.” In some cultures, home buyers may be more likely to act swiftly if the address, potential move-in date, or geographic coordinates of the house’s location are deemed auspicious by an authority greater than themselves.

Here’s another pair of contrasting proverbs from two other countries:

Avoid men who do not speak and dogs that do not bark. (Brazil)

As I can attest from my time living in Brazil, verbal communication is extremely important. As the proverb suggests, Brazilians tend to be more wary of people (or animals) who are relatively quiet than of those who are loquacious and loud. In Brazil, I’ve found that interrupting during conversations and meetings is common and often expected, and that opinions tend to be offered freely and more frequently compared to many other cultures. These characteristics were highlighted at the 2016 Rio Olympic games, where people from around the globe were struck by the boisterousness of Brazilian fans—especially during events that tend to be more quiet, like ping-pong.4 The experience was summed up perfectly by this headline from the Denver Post: “Boisterous Brazilian fans rewrite rules of Olympic etiquette.”5

Silence is golden. (Germany)

Although its origin is German, the proverb “Silence is golden” is widely used in parts of Europe as well as North America. The expression underscores the value of silence in certain contexts (but not always), and can suggest that speaking isn’t always necessary to acknowledge the moment. It also suggests that some things are better left unsaid. While “Silence is golden” is not the exact opposite of the Brazilian proverb, it does underscore differing perceptions and expectations around the pros and cons of being quiet.

There are also those proverbs that may be used by two different cultures but mean very different things. Take, for example, the U.S. proverb “A rolling stone gathers no moss.” This proverb is also used by Japanese, but it means something very different in each culture. In the United States, it suggests that someone should not remain idle; that it’s always better to continue moving forward and be active, even if it’s not necessarily advancing any particular goal. From the U.S. perspective, the moss symbolizes stagnation and deterioration.

In Japan, however, moss is viewed as a plant that adds beauty and refinement to buildings and gardens as they age. Here, the moss symbolizes the virtues of being patient, and how the value and beauty of something (or someone) can grow with age.

The moss clearly stands for different things in each culture. The differences in the way the proverb is interpreted also underscore differences in cultural ideologies. In Japan, patience is valued as an essential part of the path to success; in the United States, perpetual action is advocated as a way to flourish and succeed.

While age-old proverbs like these do not always reflect the current zeitgeist of a nation or culture, they do point to a set of values embedded in the psyches of earlier generations, many of which have left an indelible mark on the way that people today act and react in various circumstances.

We can’t know the values of every culture or person, but by taking stock of proverbs used in our own cultures, we are reminded that there are differing factors that shape perceptions and behaviors in other cultures, and we become less likely to have the kind of negative reactions that stand in the way of building successful connections.

PROVERBS WORTH PONDERING

Consider how these proverbs may reflect cultural beliefs, values, or aspirations.

• A wise man never plays leapfrog with a unicorn. (Tibet)

• A sleeping fox finds no meat. (Brazil)

• Fry the big fish first, the small ones after. (Jamaica)

• A journey of ten thousand steps starts with the first one. (China, Lao Tzu)

• It is good to know the truth, but it is better to speak of palm trees. (Arab nations)

• Truth is like fire; it cannot be hidden under dry leaves. (Africa)

• Stretch your legs as far as your blanket will allow. (Bahrain)

• Sticks in a bundle are unbreakable. (Kenya)

Recognizing Your Reactions

Another good way to identify your own programming is to investigate how you react to specific situations. A simple response to an everyday situation can be revelatory in terms of what you value and what you expect. Try to imagine how you would feel and act in each of the following scenarios. Don’t think about it too much; just note your gut reaction to each question, then read the follow-up examples.

You are thirty minutes late to a meeting at work, and everybody on the team is there already. How do you feel? What do you do or say?

For people raised in cultures where punctuality is highly valued, like the United States, we may feel a bit embarrassed by our lateness and offer an apology, along with an excuse to make it clear that it was not our fault. But if you were from a place like Singapore, you may have been taught that interrupting the meeting with an excuse would be construed as a worse offense than being late.

SO WHAT?

As someone from the United States, if you showed up late to a meeting with people from a Singaporean company, your offense would only be made worse by disrupting the meeting with an apology. It would be better to just enter the room and quietly take a seat. But if you are a Singaporean and showed up late to a meeting with someone from the United States and didn’t apologize or make an excuse, it would be seen as a sign of disrespect.

You make a statement or pose a question to a colleague and are met with silence. How do you feel? What do you do or say?

Most people from the United States would assume that something is wrong if there’s no response after a couple of seconds. Perhaps the person didn’t understand or didn’t like your statement, or just doesn’t know how to answer the question. When awaiting a reply, the silence might begin to make the questioner feel increasingly uncomfortable with each passing moment. In the hyperverbal U.S. culture, silence is often perceived as a symbol of distress.6

But in places such as China and Switzerland, the notion of an “awkward silence” is much less prevalent. In these cultures, silence is generally considered socially acceptable and could be imbued with a range of meanings, depending on the context; from avoiding a debate that might disrupt social harmony to simply taking time to contemplate the question and formulate a thoughtful response.

A 2009 study from the University of Ilorin explored how silence is often used as an integral and “communicatively valued piece of ‘language’” in Nigeria. Just like spoken words, silence is interpreted in different ways depending on factors such as context and who’s participating in the conversation.7

SO WHAT?

The default response to prolonged silence in the United States is often to fill the void with noise, forced laughter, or additional questions. If you were to do this with people from cultures in which silence is more acceptable, you would run the risk of interrupting someone’s thought process, disrupting the flow and tone of the conversation, and missing out on an opportunity to gain valuable information. In these cultures, unnecessarily filling silence can be associated with immaturity and selfishness, and mark someone as being overly eager.

A guest helps a host carry dirty dishes into the kitchen after a meal. Your thoughts?

This behavior tends to be highly regarded as polite, thoughtful, and humble in many cultures. A host may refuse an offer to help any further with the dishes, but it’s always appreciated when guests ask. A guest who doesn’t offer can be seen as unappreciative of the hospitality.

However, in some cultures (like Saudi Arabia, Mexico, and Korea) the act of clearing dishes or even offering to help could be construed by the host as disrespectful, possibly suggesting that he or she was doing a poor job.

SO WHAT?

If you are invited to a colleague or customer’s house and start clearing the dishes as a show of gratitude, you may actually be insulting the host, whose expectations are different from yours—thereby weakening the relationship and jeopardizing future business deals. On the flip side, if a guest to your home does not offer to help after a meal, don’t automatically assume they are being disrespectful or not thankful.

Imagine you are walking down the street and you see someone kick a dog to get him to move out of the way. Your reaction?

Most of the people I know would be outraged. Having grown up with Fido as our best friend, it’s hard to imagine why someone would intentionally hurt a dog—including strays. Witnesses might scream bloody murder, accusing the offender of unwarranted cruelty. In a dog- loving culture, kicking a canine is an unthinkable act, sometimes even less acceptable than kicking a family member.

But what if you witnessed this incident in an area where many dogs carry rabies and frequently attack people—for example, in certain parts of India or Romania?8 What if it happens in an impoverished neighborhood where dogs have been known to steal food from the plates of malnourished children? If you grew up in a place like this, the sight of a dog might scare you, and you might actually be relieved that this person kicked the dog out of your path. Even if you believe that it is inhumane to kick an animal for any reason, you now have some insight into why that person kicked the dog.

SO WHAT?

We may not like the way other people act or what they believe, but suspending judgment and considering the possible roots of the behavior is the first step to recognizing the diverse ways in which people around the globe have been culturally programmed. Armed with this new information, your reaction to a situation and how you handle it may shift.

This example about the dog usually elicits the strongest reactions from people. It also underscores how our perceptions and responses can change only when we expand our frames of reference.

Programmed to Perceive

We’ve already established that people perceive and reenact animal noises differently across cultures, and that those perceptions can be hard to shake. But let’s move beyond moos and baas.

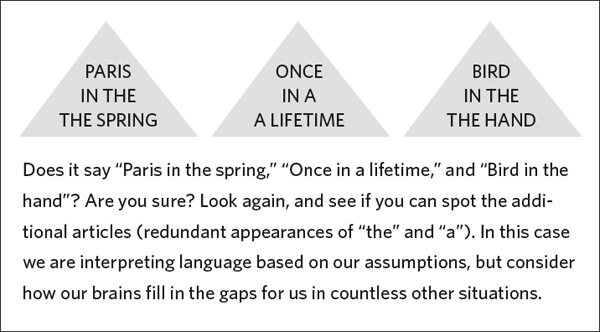

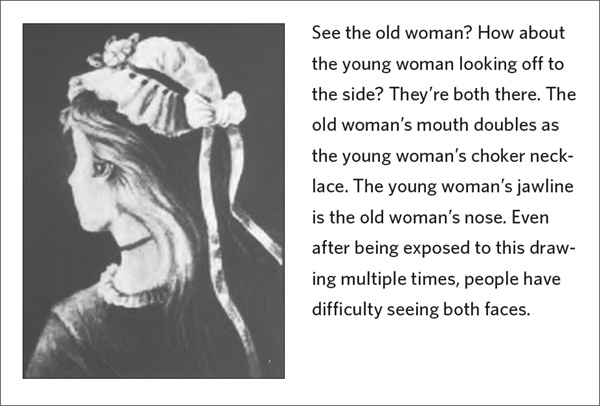

Figure 1.2: Seeing and believing

Take a look at Figure 1.2. What do you see?

The point of this exercise is to demonstrate that once we see something in a certain way, it is difficult to see it another way. If we get stuck after seeing these images just once, imagine how stuck we would get if we saw only one of the faces over and over again and no one ever noticed or mentioned the other face. After months and years of continual reinforcement, the chances of your discovering the other face on your own would be slim. Now, imagine how challenging it could be if you’ve heard, seen, believed, or done something a particular way your whole life and then were asked to perceive it another way.

Another thing about perceptions that trips us up when we interact with people from other cultures is the lack of a frame of reference for behaviors we’ve never seen before. Just as we might have missed seeing one face or the other in Figure 1.2, think about all of the cultural nuances that we might be missing just because our brains have not been primed to recognize them. This is one aspect of a phenomenon referred to in academic circles as “perceptual blindness.”9

For many years a story has been circulating about the Europeans’ initial approach of the New World, which illustrates this notion of perceptual blindness. According to one account, the Native Americans could not see Christopher Columbus’s tall ships in the distance even though they were staring straight at them. One theory is that they couldn’t see the ships because it was incomprehensible to them that boats of that size could exist. Another theory is that they observed the ships, but couldn’t even begin to identify these hulking shapes.10

Although the validity of these accounts is a bit dubious, there are other documented examples of this particular kind of perceptual blindness, including one by the American inventor Thomas Edison.

Edison made a curious observation when he beta tested the phonograph, which was first developed to play back recordings of people speaking. When he pulled random people off the street, none of whom had heard of the phonograph before, and played them a recording of a simple sentence, most people couldn’t make out what was being said. No matter how many times he played it, they still couldn’t understand it. But if the person was told what was being said in the recording, they would be able to hear it clearly the next time they listened.

This account was chronicled by Edison biographer Randall Stross, who also included Edison’s own speculation about what had occurred: “They do not expect or imagine that a machine can talk hence cannot understand it[s] words.”

Stross also noted that that the same phenomenon was observed when people used a telephone for the first time.11

These observations illustrate how our brains can be a little slow on the uptake when we are so utterly unfamiliar with something. When we cross cultures, lack of contextual reference points can easily jostle our mental operating system. Although sometimes we take these moments in stride, more often than not they will trigger emotions such as surprise, wonder, confusion, and even anger.

Consider the simple act of slurping your soup, for example. When I was growing up, slurping at the dinner table was considered an unacceptable behavior that my mother was always quick to silence. So you can imagine my shock the first time I dined at a restaurant with a Japanese colleague who fervently sucked up her noodles. I was still somewhat appalled, even though I knew that slurping is an expected and appreciated sign that someone is enjoying his or her food. But imagine how appalled I would have been if I didn’t know that slurping was considered good manners.

When perceptions have been reinforced throughout our lives, we stop paying close attention to them. In our daily lives we make unconscious split-second assumptions about what we are seeing and what things mean.

Try reading the phrases in Figure 1.3 and you’ll see what I mean.

Our minds do this because they are hardwired to minimize effort, automating our perceptions so that we can devote mental energy to other things.12 But if we just allow our perceptions and interpretations to run on autopilot without considering other frames of reference, we’re likely to run into trouble on the cross-cultural playing field. And although training your mind to expand its frame of reference is doable, it’s no small feat, considering what we’ve learned in recent years about how culture literally shapes our brains.

Figure 1.3: Reading and believing

Our Brains on Culture

People from different cultures tend to look different from each other. I’m talking about physical appearance: things like skin, hair, facial features, and so on. This is not news. What is newsworthy is that our brains look different too.

Emerging evidence from a new field of research known as cultural neuroscience is just beginning to shed light on how culture physically molds our brains. Our respective cultures forge neural pathways in distinctive patterns, organizing our brain functions in ways not previously thought possible.

Neuroscientists have long believed that each cognitive function—such as seeing, listening, analytical thinking, and emotional response—occurs in the same distinct areas of all brains. But through the use of fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) scans and other brain-imaging technology, researchers have been able to show that people from different cultures actually use different parts of their brain for all of these functions, whether they are listening to music, looking at people’s faces, or crunching numbers.13

“When you are exposed to a culture over a lifetime, your brain reorganizes,” says Jamshed Bharucha, president of Cooper Union and former Tufts University psychology professor. “The connections between the neurons change, then the brain develops these cultural lenses through which you perceive the world.”14

Recent research has revealed that culture can even override genetics, including a predisposition to depression. Former Northwestern University psychologist Joan Chiao discovered that a disproportionate number of people from East Asian cultures have a genetic trait that makes them more susceptible to depression than people from the United States, yet Americans have a much higher incidence of depression. This puzzling discovery lead Chiao to conclude that the collectivist nature of East Asian cultures could affect the way that depression genes express themselves. In other words, being a more group-oriented culture may help stop depression from manifesting in individuals. Chiao also speculates that collectivist instincts may have actually coevolved with genetic traits, as a means of offsetting the tendency toward depression.15

While studies like these are starting to reveal how deeply culture affects our minds, that doesn’t mean that we are all forever destined to think or act in certain ways. Our cultural programming creates habits, and just like the many personal habits we accumulate over the course of our lives that we may try to alter—from cracking knuckles to smoking cigarettes—culturally induced habits are deeply forged and hard to shake. In some ways, cultural habits may be even tougher to break, because everyone else in our community is doing them too. And because we aren’t even aware of them. But there are pathways to changing almost any kind of habit once we become aware of it.16

As an example, consider the case of Korean Air, whose poor safety record and numerous crashes in the 1990s seems likely to have stemmed from cultural programming related to hierarchy. Brought to the public’s attention by Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, there was a widespread belief that the Korean copilots were afraid to point out mistakes or disagree with the captain because their deeply embedded cultural programming dictated that they defer to the judgment of their superiors. Gladwell also notes that the sophisticated planes they were flying were intended to be piloted by a flight crew working as equals, not a single leader.17

According to one of the pioneers of cultural neuroscience, the late Tufts psychology professor Nalini Ambady, Korean Air pilots have since succeeded in modifying some of those cultural reflexes that may have compromised their performance and jeopardized lives. Today, Korean Air’s record is in fact greatly improved. “What cultural neuroscience shows,” said Ambady, “is that the brain is not fixed—it’s malleable.”18

While the benefits can be vast, changing your cultural habits is admittedly not simple. There is, however, a three-step method that you can apply in many situations to enhance your ability to curb your cultural reflexes. It’s the same method I share with all of my clients:

1. Recognize your own cultural programming.

2. Open your mind to other ways of perceiving or approaching a situation.

3. Adjust your response to optimize results.

The more you sift through your cultural baggage and recognize your own cultural programming (step #1), the easier it will become to put the next two steps into action. Getting to the bottom of your bag won’t happen overnight. I’ve been at it for several decades, and I still regularly discover new aspects of my cultural programming.

But now that your own process of self-discovery is under way, you’re ready to take the next step and open your mind to other ways of thinking (step #2), following in the footsteps of intrepid anthropologists and a Dutch guy from IBM.

Breaking It Down: The Dimensions of Culture

Although revelations from the field of cultural neuroscience are undoubtedly exciting and enlightening, we don’t need brain scans to hack our cultural “coding,” thanks to decades of work by experts who have studied the effects of culture and devised maps to help guide us through this convoluted terrain.

The first explorers were cultural anthropologists like Margaret Mead and Franz Boas, whose studies helped demystify the lives of little-known indigenous peoples around the globe—and whose observations and methodical analyses helped form the basis of the modern-day investigations. Next came the interculturalists, whose studies focused in on the way that cultures relate to one another—a field usually attributed to the work of pioneering anthropologist Edward Hall in the 1950s and ’60s. Hall’s work spawned a generation of intercultural experts and analysts who dedicated themselves to figuring out how a greater understanding of cultural differences could be used to achieve a variety of goals, from diplomacy to sales to organizational effectiveness.

The earliest and most widely known studies of the intersection between business and culture were conducted at IBM by a Dutch industrial psychologist named Geert Hofstede. Starting in 1965, Hofstede worked in-house with international colleagues to assess the attitudes of IBM’s workers around the globe, hoping the results would reveal how to improve company productivity. His background was perfect for the job; he was not only a social scientist but also a mechanical engineer (so he understood technical lingo), and he had spent time working at different kinds of factories, from hosiery to textiles. He could also converse in five languages—Dutch, English, French, German, and Italian—all of which he began learning in Dutch grade school in the 1940s.

At IBM, Hofstede and his colleagues conducted “attitude” surveys with employees from forty different countries, all of whom were asked the same questions. As the results of the surveys began to amass and analysis got under way, he noticed that attitudes and associated behaviors seemed to play out along cultural lines. Intrigued by his findings, Hofstede took a sabbatical from IBM to do more research at a university in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he eventually took a teaching position and continued to analyze the data. In 1980 he published his findings in a book, Culture’s Consequences. In 1991 he came out with a lay version (although still fairly academic): Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. It became an international best seller.

In a nutshell, Hofstede was among the first to offer proof that national and regional groupings (cultures) affect the behavior of people within organizations. Although his findings have been questioned for reasons such as the fact that his research was mostly limited to white males, it brought wider attention and credence to the impacts of culture on organizations. It provided a starting point for conversations about an understudied subject with vast implications for business, political diplomacy, and, now, for life in our global communities.

Hofstede also became known for the way that he broke down behaviors into five categories or dimensions, as they are often referred to. Unlike the dimensions described by Hall and other scholars who came before him, Hofstede’s take was more directly applicable to the needs of businesses and organizations. In Hofstede’s initial study, these dimensions included matters like whether people place an emphasis on hierarchy or equality, whether they embrace uncertainty or avoid it, whether they are generally more concerned with individual needs or with group harmony, and whether they value traditional male attributes such as assertiveness and competitiveness or stereotypical female traits such as being nurturing and cultivating relationships.19

Within each dimension, people fell along a spectrum, from those who demonstrated extreme attitudes (either very individualistic or very group oriented, for example) to those who acted in ways that were more middle of the road. Of course, Hofstede recognized that there were exceptional people who fell outside his theoretical spectrums. The inexact nature of his theories sparked controversy, but his findings also prompted much-needed inquiry.

Over the years many scholars have continued to refine, expand upon, and adapt the notion of dimensions to suit the needs of different communities. No version is right or wrong; culture is a vast and amorphous subject area that warrants being poked from all sides.

The next six chapters of this book present my own riff on the dimensions of culture that highlight tendencies I believe will provide the most benefits to people today—tendencies that have the greatest influence on how we communicate and interact with people from other cultures at work and in everyday life. As you delve into each cross-cultural topic, you’ll begin to acquire a new awareness of the wide range of perceptions, beliefs, and values that influence people’s behaviors. You’ll also come away with a set of applicable skills for navigating cross-cultural interactions in different circumstances.

Each of the topics I cover is worthy of its own book, and there are plenty of other important topics that warrant deep investigation, like cultural views of gender. But the point of this book is to provide an introduction to the many ways that culture impacts you and everyone with whom you interact, helping establish a solid foundation on which to launch your deeper dives into specific topics and cultures.

The Case for Generalizations

In many circumstances, making generalizations is a bad idea. It can lead to the development of prejudices, which in turn can lead to all sorts of negative fallout. When it comes to understanding cultural differences, however, a little of the right kind of generalizing can go a long way toward better understanding.

There is no denying that certain groups of people tend to share similar sets of ideologies and associated behaviors. That’s not to say that every person within a culture acts the same way or believes the same things. For example, not all Germans have a relatively direct style of communication, nor are all Japanese people indirect communicators. But there is a great tendency for people from those cultures to act one way or another. As a native New Yorker, my wife grew up with people who were very direct communicators. “You could use a haircut” or “How do you get away with charging that much for a cup of coffee?” are the kind of statements regularly issued by some of her old friends. They act in a way that seems in accordance with the tendency of people from New York to be direct. Does this mean that they are always direct? Of course not. Are there New Yorkers we know who tend to be more or less direct? Certainly.

People exhibit shared cultural traits to varying degrees and in different ways depending on the circumstance and individual personality traits, among other factors. Cultural generalizations merely offer a starting point for figuring people out. Most Korean people eat with chopsticks. Many Swiss people are punctual. Brazilians often show up late to social functions. Taken out of context or laden with judgment, these statements can be construed as offensive, but as a comparative tool for anticipating how someone is most likely to behave—and correctly interpreting the behavior—generalizations are indispensable.

Although they do not ring true in every case, calling attention to the tendencies of certain groups of people reminds us to consider other ways of thinking. The stories and statements I’ve included in this book are meant to be deconstructed, challenged, and applied in thoughtful ways. Any generalizations are intended to help you open your mind, not close it.