Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Designing Transformative Experiences

A Toolkit for Leaders, Trainers, Teachers, and other Experience Designers

Brad McLain, PhD (Author)

Publication date: 05/30/2023

Transformative experiences are life events that change our sense of self in important ways. How do they work? What elements do they require? How can we learn to design them intentionally?

By embracing the research-based approach of ELVIS (the Experiential Learning Variables and Indicators System), this book details how to recast yourself as an Experience Design Leader, one that can provide those in your organization with the opportunities needed to reflect and grow as individuals.

Beginning with the ELVIS Framework, you will gain deep foundational insight into how transformative experiences work. And then with the ELVIS Toolkit, which includes seven practical design elements, you will have the key to unlocking these powerful experiences for yourself and others.

Whether you are new to the idea of designing experiences for others or are a seasoned veteran, ELVIS shows you how to tap into the psychology operating behind the most powerful and important experiences of our lives-those that shape who we are.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( [email protected] )

Transformative experiences are life events that change our sense of self in important ways. How do they work? What elements do they require? How can we learn to design them intentionally?

By embracing the research-based approach of ELVIS (the Experiential Learning Variables and Indicators System), this book details how to recast yourself as an Experience Design Leader, one that can provide those in your organization with the opportunities needed to reflect and grow as individuals.

Beginning with the ELVIS Framework, you will gain deep foundational insight into how transformative experiences work. And then with the ELVIS Toolkit, which includes seven practical design elements, you will have the key to unlocking these powerful experiences for yourself and others.

Whether you are new to the idea of designing experiences for others or are a seasoned veteran, ELVIS shows you how to tap into the psychology operating behind the most powerful and important experiences of our lives-those that shape who we are.

Brad McLain, PhD, is a social scientist interested in the nature and psychology of transformative experiences, identity development, and leadership. He is the Director of Corporate Research at the National Center for Women and IT (NCWIT) where he routinely works closely with companies including Apple, Intel, Facebook, Google, and dozens of others. He is also the Director of the Center for STEM Learning at the University of Colorado at Boulder, has served on the Board of Directors for the Jane Goodall Institute, and chairs Dr. Goodall's Roots&Shoots educational program national leadership committee. His TEDx and TEDx Youth talks, podcasts, and other work can be found online.

1 ■ ELVIS Overview

Sometimes we are lucky enough to know that our lives have been changed, to discard the old, embrace the new, and run headlong down an immutable course.

—Captain Jacques Cousteau,

The Silent World

You’re probably better off if you just shut up and play.

—Elvis Andrus,

American baseball player

It is the heartbeat of ELVIS Experience Design Leadership, and so I repeat it often throughout this book: transformative experiences are learning experiences that have an identity impact, changing the experiencer’s sense of self in some important way. It is the identity component that drives such experiences and makes them internally generated, no matter the external circumstances or triggers that may surround or initiate them. This makes them different from any other significant or extraordinary experiences in our lives.

A transformative experience is one that has an identity impact, changing the experiencer’s sense of self.

In defining a transformative experience this way, several questions emerge that are important for leaders wishing to learn how to design such experiences:

• In what way is an experience transformative?

• Are there different types of experiences or types of transformations?

• How transformative was a given experience?

• Is there a continuum or some kind of 10-point scale for transformative-ness?

• So what if you have a transformative experience? What difference does it make in your life or in the world?

The answers to these questions vary widely because transformative experiences are subjective in nature, which makes perfect sense if their source is internal to us. Therefore, on the surface, transformative experiences can look very different from one another, depending on a wide range of experiencers and experiences and whether they are designed or undesigned, initiated by external events or driven by internal ones.

When we look closely at the nature of transformative experiences across this wide range, certain commonalities emerge. First, they all track through the same basic sequence of stages. And while not a code or a formula, this sequence composes a framework for understanding how transformative experiences operate and how we can become skilled designers of them. This is the ELVIS Framework.

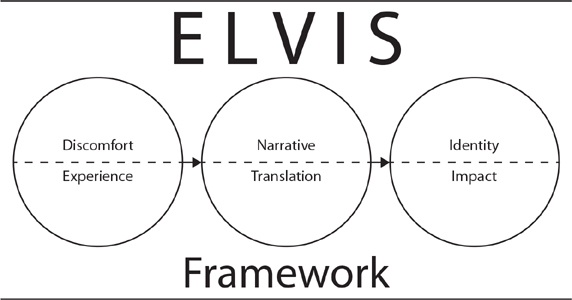

Recall that ELVIS stands for “Experiential Learning Variables & Indicators System.” The ELVIS Framework is the underlying structure of the system. There are three components to the ELVIS Framework, which we will unpack in the next three chapters. They are as follows:

1. Discomfort zone experiences, which include experiences of many different kinds but that invariably incorporate personally relevant learning about ourselves and the worlds we live in

2. Narrative translation of experience, which is the way we convert our experiences into personal understanding and make meaning from them

3. Identity construction, our dynamic and constant process of becoming, which determines who we are psychologically, as well as what we do, what we think we can do (or even attempt), who we aspire to be, and how we transform

The framework works like this (see figure 1): Transformative experiences fall into different discomfort zones (the subject of chapter 2) according to their details and circumstances—events, themes, context, and other internal and external factors. Ultimately, we translate these experiences into narratives of different kinds, something that we are naturally quite good at and that our brains are hardwired to do (precisely how and why is the subject of chapter 3). Our most powerful experiences are translated into our most important narratives. If these experiences and their resulting narratives are important enough, they become part of our identity narratives. Identity narratives (the subject of chapter 4) live in that very special and carefully guarded library of volumes within our heads that contain our most personal and valuable possession: our sense of self. These are the stories that inform who we are, how we experience life, what we can do (and what we cannot do), and who we want to become. When an experience alters our sense of self through this process, it becomes a transformative experience, and it has the power to change our lives from within, the lives of others, and the world beyond.

Figure 1: Experiential Learning Variables & Indicators System

Think again of your own most transformative experience so far, but now see it through the ELVIS lens. What discomfort zone elements were included? What kind of narrative did you construct from it? How did the experience, through that narrative, change your sense of self?

Understanding the details about the three main components of the ELVIS Framework (the subject of the next three chapters) unlocks a powerful design platform for creating these kinds of experiences as leaders in many domains, and even for ourselves.

But of course, there is more. Emerging from the ELVIS Framework are additional commonalities that help us further understand the broad-stroke nature of transformative experiences and give us insight on how best to design them. Here I will highlight two of the most important: “bake time” and “life invitations.”

Transformative Experiences Often Require “Bake Time”

Part of the nature of transformative experiences is that they often require some “bake time” for this full process to happen. For example, the space shuttle Columbia tragedy I described earlier stretched me into several discomfort zones over time, including feelings of being lost, sad, angry, fearful, and disillusioned, variations of which are quite common in transformative experiences.

On the very eve following the accident, a CBS news crew was in my house interviewing me about the tragedy. My attempts to describe my experience at that time were completely inadequate and inarticulate. I did not have the perspective or the language to make meaning of it all so suddenly. Looking back now, I understand my early lack of narrative clarity as a kind of necessary ineptitude. It was the forging fire required for me to properly narrate what I was experiencing and how I was changing in a way that would guide me through it. Only after I surfaced from the postaccident period almost a year later did I recognize myself as someone else, as fundamentally changed.

Think of an experience you’ve had that changed with bake time. Maybe it’s the way you think about a school experience from way back, a current or past relationship, or a significant job change. Perhaps it’s an adventure you had or a group experience you shared with others. We often notice these kinds of bake-time changes best by examining how we tell the story: the setup, the plot points, the details, and the conclusion. What stories of yours have you changed the telling of as you’ve gotten older? It often takes weeks, months, or even years for people to make meaning from their most powerful experiences.

The most critical stage of an experience is still occurring even after the most observable parts are over.

Importantly for leaders who design transformative experiences, bake time suggests that the most critical stage of an experience—the deeper inward journey—is still occurring even after the externally “designed” or most observable parts are over. It also tells us that transformative experiences are dynamic over time, with meanings that evolve as we integrate them into our larger life narratives and grow older (and hopefully wiser). They do not stop when the primary designed experience is “complete.”

Despite (or maybe even because of) our best-laid plans as experience designers, eventually our designed transformative experiences take on a life of their own. Ultimately, the leader must step aside and give the design away to its unfolding in the hands of those who live it and who must therefore narrate it. When this happens, a new and very personal dimension of the experience is budding—and it is a very good sign. The very best we can do as designers is to recognize this important moment in the process and accommodate it, help structure it when we can, but also let it fly when the wind of it meets the new wings the experiencer has grown.

Ultimately, the leader must step aside and give the design away to its unfolding in the hands of those who live it.

Transformative Experiences Are Life Invitations: What I Learned from Cancer, COVID, and Divorce

The moment you’re told that you have cancer is a transformative experience. Whatever your hard-won or intricately assembled identities might have been before this moment, in an instant a new and unwanted identity bursts to the top of your priority list: “cancer patient.” For me, it was a truly surreal moment, indelibly changing my sense of self and an example of life offering me an invitation that was, at first, very hard to see.

I was conducting some leadership workshops at Apple, at the Apple One headquarters in Cupertino, California. The facility is a beautiful round building of glass about the size of the Pentagon, and locked down with incredibly tight security. Escorts were required for visitors like me to even walk to the restrooms. We had just broken for lunch and were moving into the hallway when my phone buzzed. I recognized the number as my doctor, and I knew she had my biopsy results. Not wanting to take the call in front of my workshop participants or team colleagues, I spied someone just leaving their little office a few doors down. As the office door slowly started to close, I hustled over and managed to slide my foot over the doorjamb just in time and ducked quickly and quietly inside. Certainly it was a breach of the rules, but I hoped my friends at Apple would forgive me for seeking a moment of solitude.

“I have your results,” she said. “It is a malignancy. You have cancer.” I felt a trapdoor open beneath my feet. Down I went, falling into myself. My doctor continued on with additional details and next steps, but after the cancer proclamation, all I heard were distant and unintelligible words, as if in a foreign language and far away. What is that old saying, that each of us is only a single phone call away from our knees? This was that call for me, as I slowly slid down the glass window to the floor, to my knees.

My heart and mind were racing one another at warp speed. I began to sweat. And then very slowly, very gently, a singular silence descended on me. I remember looking out that window into the middle of the donut-shaped building, where an external green park was, and thinking, “How simple and lovely is this scene.” Time slowed. Leaves swayed in the breeze. Birds flew in slow motion. I became numbingly detached. I felt like I was observing someone else living this moment, not me. It was what psychologists call a state of temporary depersonalization, not uncommon during high stress or shock. For me, it marked a threshold crossing from the familiarity of my prior existence and my prior self into a new life by way of an extreme discomfort zone—the first component of the ELVIS Framework.

When I emerged from the room, I announced the news to my colleagues, “I have cancer.” And in simply uttering those words myself, my detachment was over. It suddenly became true. Those three words became one of the shortest and most important narratives in my life—the second component of the ELVIS Framework. And with that, I instantly became a cancer patient and took on a new identity—the third and final component of the ELVIS Framework.

It was a transformation that I was all too conscious of happening in real time. It was also the fastest whiplash experience of ELVIS I have ever known. As I said, transformative experiences often require bake time, almost like water seeping through rock. But sometimes they bake fast, striking like lightning!

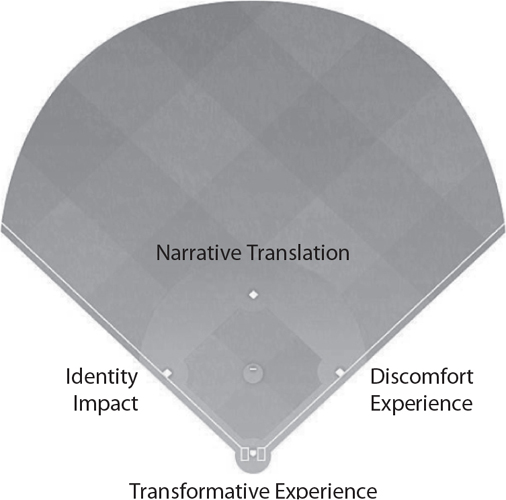

Put another way, if the ELVIS Framework were a baseball diamond (see figure 2), how quickly you round all the bases depends on what kind of hit sets you running. In this case, the hit was a deep fly ball to left center field and then continuing on right out of the park that sent me around all the bases in a single shot, a most unwelcome home run.

After years of unpacking and examining hundreds of rich and complex transformative experiences from people across all walks of life through my research (including the intricacies of their discomfort zone experiences, the variations and layers of their resulting narratives, and the multifaceted identity impacts that formed their ultimate outcomes), here I was faced with a mind-blowingly simple, inescapable, and heart-wrenching reduction of the entire ELVIS Framework in its starkest, meanest terms. The full cycle in a matter of minutes. I was in awe of life’s powerful hand and the fragility of my stability. What I did not know then, and what all cancer patients reading this will know all too well, was that it was only the beginning of a series of transformative experiences. They would seismically ripple through the landscape of my sense of self from the epicenter of that time and place, in that little room, in Apple One.

Figure 2: Baseball Analogy

Whether sudden like the crack of a bat or slowly evolving with lots of bake time, the fundamental nature of any transformative experience is that it is an invitation life is making to us. Oftentimes, as with injury, tragedy, or illness (as was the case for my cancer), it is an invitation we cannot refuse. However, we can decide the manner in which we will RSVP.

Looking back on the events following my cancer diagnosis, I can more clearly see the invitation life was offering. Cancer was an ambassador of change for me, ushering in a new season of my life by asking me to turn away from the past I had known and the person I had been, and turn to a future I had not expected or was prepared for. It was an invitation to live differently by accelerating the frontier of my own mortality. It brought me into real conversation with myself about the life I had been hoping for versus the life I was actually living. And it starkly highlighted what changes I needed to make. This “frontier accelerating” nature of transformative experiences is always inviting us to reconfigure ourselves and our relationship to life. In my case, many invitations subsequently flowed forth from my cancer diagnosis.

This “frontier accelerating” nature of transformative experiences is always inviting us to reconfigure ourselves and our relationship to life.

First, it laid bare the cracks in my 20-year marriage and led to its heartbreaking but ultimately inspirational unraveling. With that came an invitation to set my heart free after years of unacknowledged self-imprisonment. Cancer also invited me to redirect my career priorities toward my “passion work,” of which this book is a part. It also sparked an invitation to rekindle a long-neglected yet deeply treasured friendship I thought I had lost. And perhaps most deeply, it brought forth an invitation to change my identity as a father from someone expected to have all the answers to someone guiding and sharing in the asking of life’s beautiful questions alongside my two children, even if sometimes scary.

All these invitations occurred for me just as COVID was ramping up as a global pandemic. On the still-raw heels of my recovery from cancer and in the midst of my divorce, the utter weirdness of my own internal life was externally echoed in the weirdness of the new normals of the COVID world: isolation and quarantines, closings and lockdowns, mask wearing, hand sanitizers, scrubbing down our groceries, homeschooling, rampant illness, clogged hospitals, and rising death tolls. The media airwaves became saturated with all kinds of COVID-related coping advice precisely as I was struggling to put my life on a new track. I could easily close my eyes and imagine all this helpful guidance was intended just for me. All I had to do was turn on the radio to get “three self-care tips for getting through the day” or turn to social media for the latest “COVID stress-management steps to follow this week.” They might as well have had my name on them: “How to deal with isolation and uncertainty . . . for Brad.”

Like hundreds of millions of others, I was infected by COVID during the writing of this book. COVID is a transformative experience that is continuing to change all our lives, for some much more than others. On an individual level, it has been an unwanted (but perhaps much needed) invitation for each of us to take a hard look in the mirror and ask ourselves some fundamental questions: Who am I right now? What am I doing and why am I doing it? Is this who I want to be? At the same time, COVID has also invited us to take a deeper look outside ourselves and become more keenly aware of the struggles and transformations it has ushered in for different people in different ways. Collectively we know that already marginalized groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, have suffered more in terms of both life impacts and death rates due to COVID. Women have shouldered much more of the burden of pandemic childcare, online homeschooling for their kids, and other home-based tasks that disproportionately interfere with their careers and life balance. We know that the poor, aged, and immune-compromised are at much greater risk for all the negative consequences of COVID in every category.

When we see these differential impacts revealed in the lives of our friends, family, and neighbors, we are reminded of the intersectional nature of transformative experiences. Our transformative experiences, of any kind, occur at the intersection of all the other contexts, currents, and eddies of our lives occurring at those moments. These life contexts include our identities going into such experiences and our life circumstances at that time. Therefore, as leaders designing transformative experiences for good ends, we must recognize that any invitations we might make to our experiencers will land very differently with different people owing to this intersectional nature of transformative experiences; these experiences cut across our many identities. This is both a challenge for us as designers and a blessing, but in both cases a wonderful reminder that we are unique in our self-configurations and that we are, each of us, living lives never lived before in the entire history of history. The future is open wide to us.

Exercise

Cast yourself as a social scientist for the moment and unpack your most transformative experience using the ELVIS Framework. In what ways was your transformative experience a discomfort zone experience? How do you tell the story of this experience, and how has your telling of it changed over time? How do people close to you tell the story about your changes from their perspectives? How did the experience narrative change or inform one or more of your identity narratives, the stories that form your sense of self? Looking back, we can also now ask, what would you change about your experience if you could? This brings us into the mind of a designer. Keep this and other examples of your transformative experiences in your mental library. They will prove invaluable as you begin to lead by transformative experience design.

Share your stories! Visit the companion site for this book at DesigningTransformativeExperiences.com to find the Transformative Experience Forum, where you can share your own stories and questions about Transformative Experience Design with the community of ELVIS designers.