Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Equity

How to Design Organizations Where Everyone Thrives

Minal Bopaiah (Author)

Publication date: 09/07/2021

Even the most passionate advocates for diversity, equity, and inclusion have been known to treat equity as the middle child—the concept they skip over to get to the warm, fuzzy feelings of inclusion. But Minal Bopaiah shows throughout this book that equity is critical if organizations really want to leverage differences for greater impact.

Equity allows leaders to create organizations where employees can contribute their unique strengths and collaborate better with peers. Bopaiah explains how leaders can effectively raise awareness of systemic bias and craft new policies that lead to better outcomes and lasting behavioral changes. This book is rich in real-world examples, such as managing partners at a consulting firm who learn to retell their personal stories of success by crediting their systemic advantages and news managers at NPR who redesign their processes to support greater diversity among news sources. This slender book expands DEI past human resources initiatives and shows how leaders can embed equity into core business functions like marketing and communications.

Filled with humor, heart, and pragmatism, Equity is a guidebook for change, answering the question of how that so many leaders are asking today.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Even the most passionate advocates for diversity, equity, and inclusion have been known to treat equity as the middle child—the concept they skip over to get to the warm, fuzzy feelings of inclusion. But Minal Bopaiah shows throughout this book that equity is critical if organizations really want to leverage differences for greater impact.

Equity allows leaders to create organizations where employees can contribute their unique strengths and collaborate better with peers. Bopaiah explains how leaders can effectively raise awareness of systemic bias and craft new policies that lead to better outcomes and lasting behavioral changes. This book is rich in real-world examples, such as managing partners at a consulting firm who learn to retell their personal stories of success by crediting their systemic advantages and news managers at NPR who redesign their processes to support greater diversity among news sources. This slender book expands DEI past human resources initiatives and shows how leaders can embed equity into core business functions like marketing and communications.

Filled with humor, heart, and pragmatism, Equity is a guidebook for change, answering the question of how that so many leaders are asking today.

—Jody Williams, Nobel Peace Prize laureate

“Do you wish your organization was more equitable? Well, stop wishing and start designing! Equity is a guidebook for change. It's a fast and engaging read loaded with practical guidance, and it's a must-read for leaders who want to create conditions in which everyone can flourish.”

—Dan Heath, coauthor of Switch and author of Upstream

"Though this book is short, it's dense; it's meant to be studied, dog-eared, and shared throughout your organization. Just the glossary alone, with a three-page list of the most crucial concepts addressed in the book, will be enough to keep readers going back to this book regularly as a reference guide. Those looking for a way into the immense change that seeking equity requires would do well to look at this book as an elegantly written skeleton key."

—Philanthropy News Digest

"Equity: How to Design Organizations Where Everyone Thrives lives up to its title as a practical-minded guide to improving diversity, equity, and inclusion within one's organization. Chapters address how leadership can engage more effectively, the role of media and marketing in creating equity, countering bias in entrenched systems, and much more."

—Midwest Book Review

“Minal's blending of design and diversity offers a unique way of understanding both. She combines real-world experience with relevant research to deliver a thoughtful, accessible, and engaging IDEA for meaningful change.”

—Keith Woods, Chief Diversity Officer, NPR

“Minal Bopaiah has woven accessibility throughout her discussion of diversity, equity, and inclusion, highlighting its importance to leaders who want to be resilient in a volatile and uncertain world. I highly recommend this book for any organization seeking to be an employer of choice for people with diverse abilities.”

—Bonnie St. John, bestselling author, Paralympian, and Fortune 500 leadership expert

Foreword by Johnnetta Betsch Cole

Introduction: The Virtue of Equity

1 The Relationship between Bias, Systems, and Equity

2 A Design Approach to IDEA

3 Engaged and Equitable Leadership

4 Bridging the Gap

5 Communicating the Change

6 Creating Equity through Media and Marketing

Conclusion: Cocreating an Equitable World

Notes

Glossary

Discussion Guide

Acknowledgments

Index

About the Author

About Brevity & Wit

1

The Relationship between Bias, Systems, and Equity

My husband is a firefighter, which means he has no dearth of hilarious, poignant, and troubling stories about how resistance to diversity and inclusion manifests in workplaces, particularly among people who are not fond of change. One of my favorites is his story about three fire department captains who attended an out-of-state conference on diversity and inclusion. During one presentation, a speaker mentioned “LGBTQ.”

“What does the Q stand for?” one of the captains asked.

“Queer,” the speaker responded.

“Are you kidding me?” the captain responded. “Ten years ago, I literally got called onto the carpet by a supervisor for using that term.”

I suspect—and sincerely hope—the speaker then explained the term’s evolving use and its reclamation by LGBTQ+ advocates.

However, little of that sunk in. When the captain returned to his firehouse, his entire takeaway from the three-day conference was “Guys, we can say the word queer now.”

This story always makes me laugh with both bemusement and despair. Bemusement because I sympathize with a captain for whom the world has changed too fast while he was literally putting out fires. At the same time, I despair for IDEA professionals. Is this really the top message we’re delivering? Is this the takeaway from our efforts to host courageous conversations and spur people to “do the work”? And honestly, do we really need everyone to engage in a one-hour conversation about gender fluidity? I’m down for that, but I know my husband would rather do almost anything else, including all the housework he does on a regular basis while I write. And most troubling, are we implying in our conversations and reading lists that everyone needs a doctorate in social justice to be inclusive and equitable?

This is not a scalable solution. After hearing my husband’s story, I realized we might all be better served if we simply told people like him and this captain, “Listen, when interacting with people directly in the field, always ask what pronouns they use.” I wonder if that approach would yield more behavior change, since my husband’s colleagues are often willing to follow the rules in the spirit of professionalism. And department policy has the added benefit of reinforcing inclusive behaviors through sheer peer pressure.

In short, instead of emphasizing personal growth and trying to motivate everyone to be better, we could design organizations in a way that it makes it easy to do the right thing. We could say, “Here are the rules by which your job performance will be judged.” We could request specific behaviors that would ensure a more inclusive or equitable culture, such as asking new employees which religious or cultural holidays are most important to them and ensuring they have those days off. We could create organizations that are designed to work with the way the human brain works, which requires direction, motivation, and bandwidth to adopt new behaviors (more on this in chapter 2). We could be explicit in our expectations instead of asking everyone to be as passionate about IDEA as we are. This is how we can get scalable, equitable outcomes with less hand-wringing and frustration.

To achieve such equitable outcomes, we need the preconditions for equity. As we saw in the introduction, equity is possible when people with power

1. Value difference

2. See systems

3. Use their power to create more opportunity for others

In chapter 3, we’ll discuss how leaders can value difference and see themselves in relation to the systems in which they live and work. Any individual is part of multiple systems: the organizational system of a company or nonprofit, the system or process by which work gets done, and the larger societal system, such as American culture and industry norms. We need to understand these larger societal systems because they’re subtle and often made invisible by social conditioning. To help you see them, I offer a ten-thousand-foot view of the biases baked into the US societal system and culture.

Bias and Systems

Implicit bias—sometimes referred to as unconscious bias—is present in everything we do, including how we design systems. Bias happens when our minds automatically associate certain stimuli with certain thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. For example, when most of us see a red light, we automatically press the brakes without consciously thinking our way through interpreting the stimulus and responding to it. In many cases, as with this one, bias is a positive time-saver. Bias is detrimental, however, when our associations are based on stereotypes or bad data. If you don’t know any transgender individuals (and 80 percent of Americans do not), you might assume certain traits based on media representations. Or if you have been taught to fear difference, you may be irrationally fearful when presented with any sort of difference, even if it poses no objective threat, as we have seen in the many incidents of police officers killing innocent children who are Black.

Understanding bias is important because it absolutely informs the design of systems. Mahzarin Banaji, a professor of psychology at Harvard University and a pioneer in the field of implicit bias, calls bias “the thumbprint of the culture on our brain.”1 Culture is just another word for how the system helps shape behavior among a group of people. The late Geert Hofstede, a renowned scholar who conducted seminal research on organizational culture at IBM and other organizations, describes culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others.”2

In today’s America, most of us—regardless of our identity—have been collectively programmed to think of the “default” human being as White, male, straight, able-bodied, in early or mid-adulthood, Christian, and upper-middle class. Everybody else is “other.” And so, most of our systems, processes, organizations, products, and laws have been designed for this “prototypical” individual.

Actor Anne Hathaway summed up this collective programming beautifully at a 2018 Human Rights Campaign awards dinner:

The path to freedom, to equality, is currently being blocked by a big, heavy, almost invisible lie. The lie is not about whether we are equal. The lie is about whether our opportunities are. It’s important to acknowledge that whatever my actions have been, however hard I have worked, however the world may have marginalized me and my experiences, that my standing here, my ability to be visible to you, comes from the world unfairly rewarding my particular type of visibility. It is important to acknowledge that, with the exception of being a cisgender male, everything about how I was born has put me at the current center of a damaging and widely accepted myth. That myth is that gayness orbits around straightness, transgender orbits around cisgender, and that all races orbit around Whiteness.

This myth is wrong. But this myth is too real for too many. It is ancient, so it is trusted. It is a habit, so it’s assumed to be the way things are. It’s inherited, so it’s thought immutable. Its consequences are dangerous because it prioritizes a certain type of love, a certain kind of body, a certain kind of skin color. And it does not value in the same way anything it deems to be other to itself. It is a myth that is with us from birth. And it is a myth that keeps money and power in the hands of the few instead of being invested in the lives of the free. (Emphasis added.)3

We have been collectively programmed to hold certain biases. Biases become racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, Islamophobia, ableism, and other isms and phobias when they are backed by power. When power backs bias, we get racist cops acting with impunity, like Derek Chauvin, who murdered George Floyd, and top executives, like Harvey Weinstein, sexually assaulting women for years and covering it up through nondisclosure agreements. We get Latine children in cages. We get transgender people being denied their right to health care.

An oft-repeated adage in the design industry is that great design should be experienced, not seen.4 This makes racism a particularly well-designed phenomenon since, as designer, researcher, and educator Lauren Williams writes, “US constructs of race . . . have been so well designed that their existence is presumed to be fact and their operations and consequences are rendered invisible, insidious, ubiquitous, and relentlessly adaptive.”5 In other words, racism was designed to be invisible and to adapt. The same can be said of other systems of inequality and oppression. They are invisible thumbprints on our brain, influencing every decision, including our design of systems.

System Design

System design is the policies, laws, structures, institutions, traditions, and informal rules that govern how individuals operate within a given system. As I showed in the introduction, Americans—and many other people in different countries—are living in a system designed to work for some people over others, namely, White men with property. A number of iterative designs happened over hundreds of years to systematically advantage White, straight, able-bodied, Christian men with property (and property included enslaved people and women), including the following:

• The Indigenous people of America were racialized “subtractively.” Laws were created mandating that the descendants of Indigenous people meet certain “blood quantum levels” to be considered American Indian. That is, they needed to prove they were one-half, one-eighth, or one-sixteenth American Indian to qualify as such. This ensured the eventual decimation of the Indigenous population. This benefited White people because Article I of the US Constitution promises that the US government will provide Indigenous people of this land with social services in perpetuity; the eventual extinction of Indigenous people means that White people and other settler colonialists in this country could amass more of its wealth.

• Black people were racialized “expansively,” meaning that “one drop of negro blood” qualified individuals for enslavement. This allowed White enslavers to multiply their free workforce through rape and enslave their own children.

• The Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery on the basis of race but continues to allow for slavery on the basis of criminality. The system of racism adapted again and began associating Black people with “criminals,” leading to an exponential growth of incarcerated Black and Brown people in the last sixty years.6

We could go through the same historical exercise to look at the oppression of women, LGBTQ+ individuals, Jewish and Muslim people, and people with disabilities. This is how the system works for those it was not designed for: it is oppressive, it is discriminatory, and it continuously pushes back the starting line. It’s no wonder some of us can’t catch up. It’s no wonder some of us are angry and tired. And frankly, it’s no small act of nobility and grace that most marginalized people, to quote the activist Kimberly Latrice Jones, “are looking for equality and not revenge.”7

The design iterations that perpetuate injustice and inequity rest on one central lie: rugged individualism, the idea that we can go it alone and that any and all success is due solely to our own effort. Unfortunately, this way of thinking is so implicit in our minds that it is hard to undo, and various innovations to create more equitable outcomes often perpetuate the biases of these systems of oppression.

One example is a financial app for high schoolers called Moneythink. Moneythink was created by a Chicago nonprofit to solve the problem of unaffordable college education by teaching low-income teens how to manage their money in preparation for college and employment.8 But it doesn’t address the soaring cost of higher education, the systemic causes of disparities in educational outcomes, or the racial wealth divide. (Black households hold less than seven cents to the dollar compared to White households, and White families living in poverty have about $18,000 in wealth, while Black families have none.9) Nor does it address disinvestment in public schools and in Black and Latine communities through gerrymandering, redlining (when lenders refuse to operate in certain neighborhoods for discriminatory reasons), predatory lending (when lenders use unfair tactics against borrowers), and other structures.

Instead, the app looks to individuals, not society, to solve the problem of unaffordable college tuition by “coaching” teens through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and teaching them to save (with no mention of the lack of high-paying jobs for high school graduates in their communities or employers’ discriminatory hiring practices). In short, Moneythink blames victims for their own oppression and perpetuates the myth of “bootstrapping your way to success.”

A less egregious example comes from my own life. Many years ago, my younger brother hit a rough patch, and I tried to get him on my health insurance. At the beginning of my career, I worked for an employer who offered a “self plus one” health insurance package. This was a gay-friendly policy that attempted to redress the absence of marriage equality laws at the time, but it was also being used by single parents and other individuals who needed to add one person, not an entire family, to their plans. Years later, I sought the same solution for my brother but found that most health insurance companies abandoned this policy after the legalization of marriage equality. To add my brother to my health insurance plan, I had to make him my “dependent”; that meant that he would be kicked off my plan if he earned more than $2,000 a month. And yet if I married a stranger of any gender, I could add them to my insurance plan without declaring them dependent or unfit to work. In fact, that person could go on to make more money than me and still be covered by my insurance.

The bias here is an American cultural definition of family that centers the “nuclear” family, a fairly recent concept in human history that negates the ancient appreciation for extended kinship networks. While the definition of family in this country has expanded to include same-sex couples, it still hinges on notions of sexual relationship and financial dependency. My brother is my first-degree blood relative, but many Americans may believe that I don’t have a family because I don’t have children. And so, the system centers a certain type of love, a certain type of relationship, above all others.

Designing Equitable Organizations in an Inequitable System

Designing an organization where everyone thrives takes ingenuity and courage, especially if you are trying to do so in a wider system that has bias baked in (US culture, for example). But creating an organization and organizational culture that fosters more equitable outcomes is possible, no matter your size or industry. Good designers know that we cannot allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good. Designers are inherently pragmatic, which is why design is such a powerful approach for creating more equitable organizations, so long as that practicality is coupled with an understanding of systems and the ability to discover the root causes of inequity, which we’ll discuss more in chapter 2.

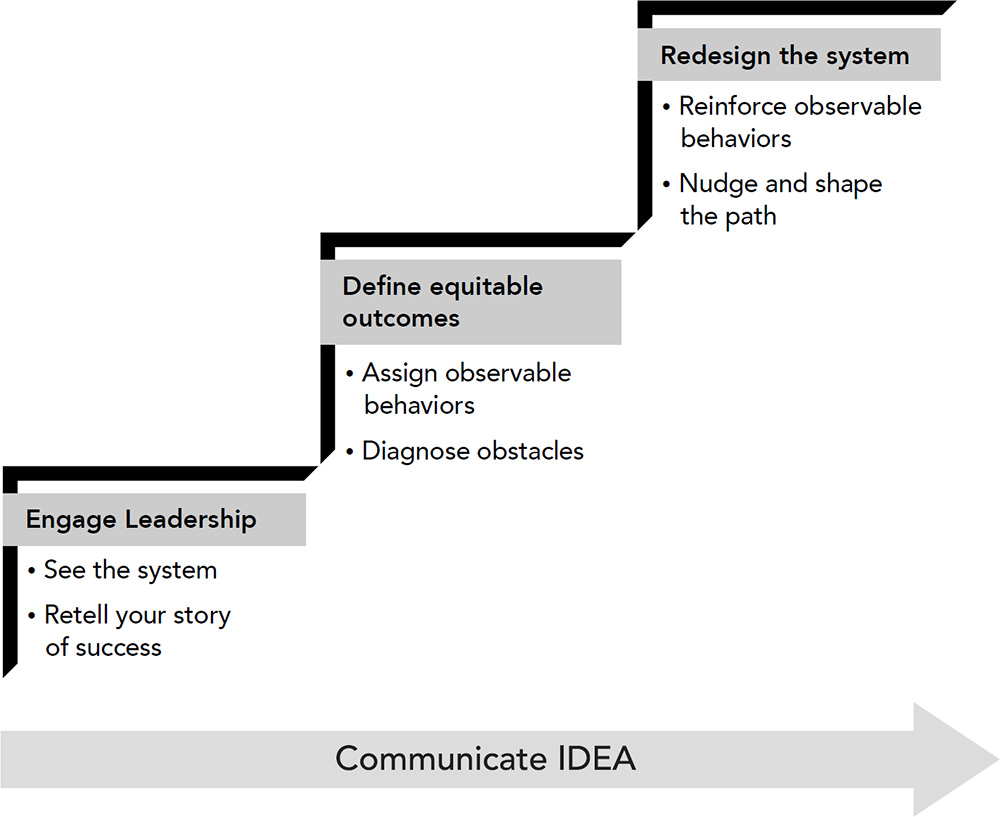

In working with clients to design equitable organizations, Brevity & Wit uses a sequential theory of change that starts with engaged leadership, defines equitable outcomes, and then redesigns the organizational system to support those outcomes (see figure 2). Engaged leadership, which we’ll cover in chapter 3, requires seeing the system, as I hope you’re starting to do, and retelling your story of success in a way that unmasks the system (both organizational and societal) for others. Defining equitable outcomes, as we’ll discuss in chapter 4, is achieved by centering those who have historically been on the margins of the organization. It also requires identifying observable behaviors, such as making it policy that firefighters ask people for their pronouns when interacting with them. Then it requires identifying any obstacles to adopting that new behavior. The identification of those obstacles will allow you to redesign the system to support the new behavior. Throughout this process, as you can see in figure 2, we are also engaging in change communications that help generate buy-in and reduce resistance to IDEA, which we’ll cover in depth in chapter 5. This theory of change will help create an organization whose impact can then be felt in the wider system and culture through media and marketing, as we’ll show in chapter 6, or through its corporate and societal impact, as we’ll discuss in the conclusion.

This model can work for both small and large organizations, although your impact may vary. Later in the book, I’ll pull from examples of my work with Evans Consulting, a small firm of fewer than one hundred employees, and with National Public Radio (NPR). Both organizations were able to establish equitable outcomes, but NPR understandably had more influence than Evans Consulting on the wider system of US culture because it is a larger organization with the ability to influence public consciousness. Evans Consulting does not have the power to change the entire industry of consulting and government contracting and, therefore, had to work within a smaller canvas of change. But what it was able to do did affect people’s lives and the organizational system.

Figure 2. Theory of change for designing equitable organizations.

Centering and Rehumanizing

At the same time, when it comes to more equitable outcomes, changing who we center is absolutely critical, regardless of the size of an organization. We must design for human nature, but that also means designing for the diversity of human nature. Leaders must learn to decenter the identities Hathaway mentions and center those that have been pushed to the margins in the organization. And this, again, is why seeing the system and understanding systemic bias is crucial.

Centering people who need and deserve better outcomes means being aware of their historical and/or current exploitation and then examining how our current systems might be perpetuating that exploitation. Some may think that management books were developed during the Industrial Revolution; in fact, extensively data-driven labor manuals were written during the era of slavery to coldly calculate the worth and value of a human being.10 The legacy of squeezing the most productivity out of a human body continues to influence the inequities we see in organizations today. As they explain in a 2020 Harvard Business Review article, researchers Robin Ely and Irene Padavic conducted an in-depth study of a consulting firm and found that the culture of overwork was more responsible than any other factor for the firm’s lack of female leaders.11 They found that women and men were equally distressed by the conflict between family and work. In fact, two-thirds of the male employees with children in the study expressed distress over this issue. Female employees with children, however, had been encouraged to make accommodations to address conflicts between work and family responsibilities, like going part-time or shifting to internal roles. Fathers, on the other hand, were generally expected to bury their feelings and work on, often to their physical and emotional detriment. “The real culprit was a general culture of overwork that hurt both men and women and locked gender inequality in place,” Ely and Padavic concluded.12 In other words, the culture of overwork was supporting old notions about gender norms as well as exploitative notions about employee productivity. In doing so, the culture was centering the needs of White men from centuries ago; it was not centering the needs of women or the needs of men in the twenty-first century.

This practice of centering people who need and deserve better outcomes is a deeply rehumanizing process. “Because so many time-worn systems of power have placed certain people outside the realm of what we see as human, much of our work now is more a matter of ‘rehumanizing,’” esteemed researcher Brené Brown writes in Braving the Wilderness, her book on belonging in our communities, organizations, and culture.13 We must begin to see the people who make up our organizations as people first and as employees second. We can no longer treat them as resources—even human resources—to leverage coldly and empirically, without warmth or care.

The need to recenter and rehumanize certain individuals and groups led me to believe in the power of human-centered design to address inequity. Of course, this isn’t a zero-sum game. By centering those pushed to the margins, we often happen upon innovations that appeal to us all, such as text messaging, which was invented for people who are deaf and hard of hearing but is now enjoyed by everyone, or flextime, which was created to accommodate parents but has been a boon to workers seeking more autonomy over their daytime schedules. So, let’s look at how we can leverage human-centered design to better serve the humans that compose our organizations.