1

Human Resource Development Boundaries

Introduction

Human resource development (HRD) is a relatively young academic discipline but an old and well-established field of practice. The idea of human beings purposefully developing themselves to improve the conditions in which they live is almost part of human nature. HRD theory and practice are deeply rooted in this developing and advancing perspective.

This first chapter highlights the purpose, definition, origins, context, and core beliefs of HRD. These highlights provide an initial understanding of HRD and function as an advanced organizer for the book. The chapters that follow fully explore the depth and range of thinking within the theory and practice of HRD.

Purpose of HRD

HRD is about adult human beings functioning in productive systems. The purpose of HRD is to focus on the resources that humans bring to the success equation—both personal success and organizational system success. The two core threads of HRD are (1) individual and organizational learning and (2) individual and organizational performance (Ruona, 2000; Swanson, 1996a; Watkins and Marsick, 1995). Although some view learning and performance as alternatives or rivals, most see them as partners in a formula for success. Thus, assessment of HRD successes or results can be categorized into the domains of learning and performance. In both cases, the intent is an improvement.

Definition of HRD

HRD has numerous definitions. Throughout the book, we continually reflect on alternative views of HRD to expose readers to the range of thinking in the profession. The definition put forth in this book is as follows:

Human resource development is a process of developing and unleashing expertise to improve individual, team, work process, and organizational system performance.

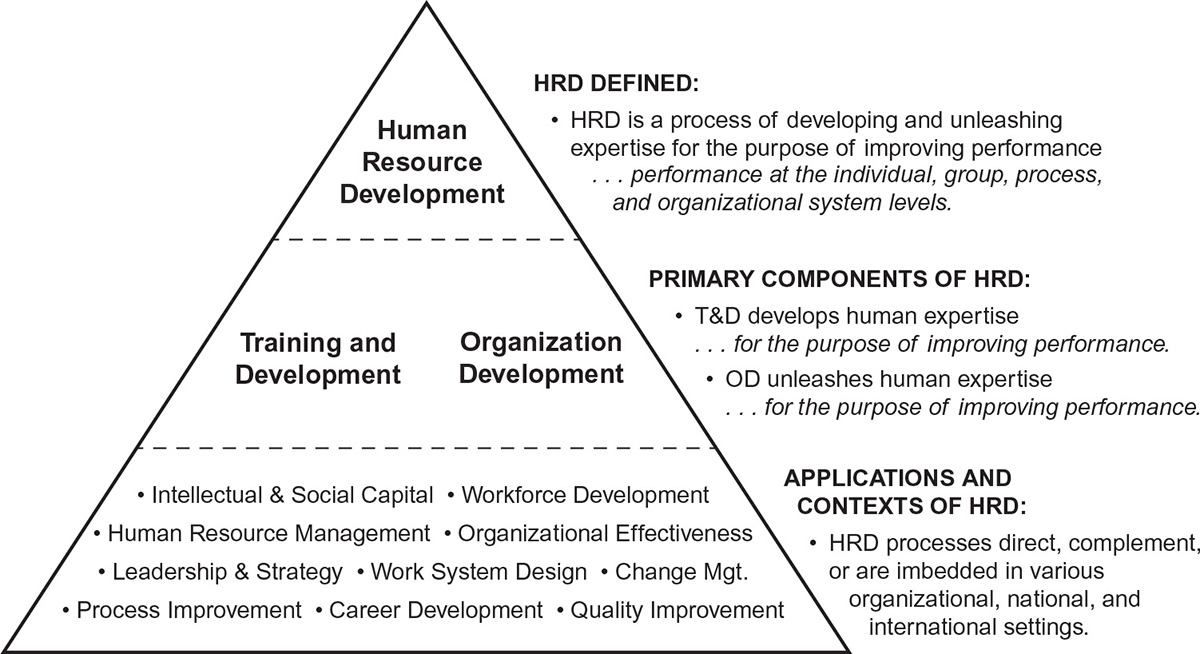

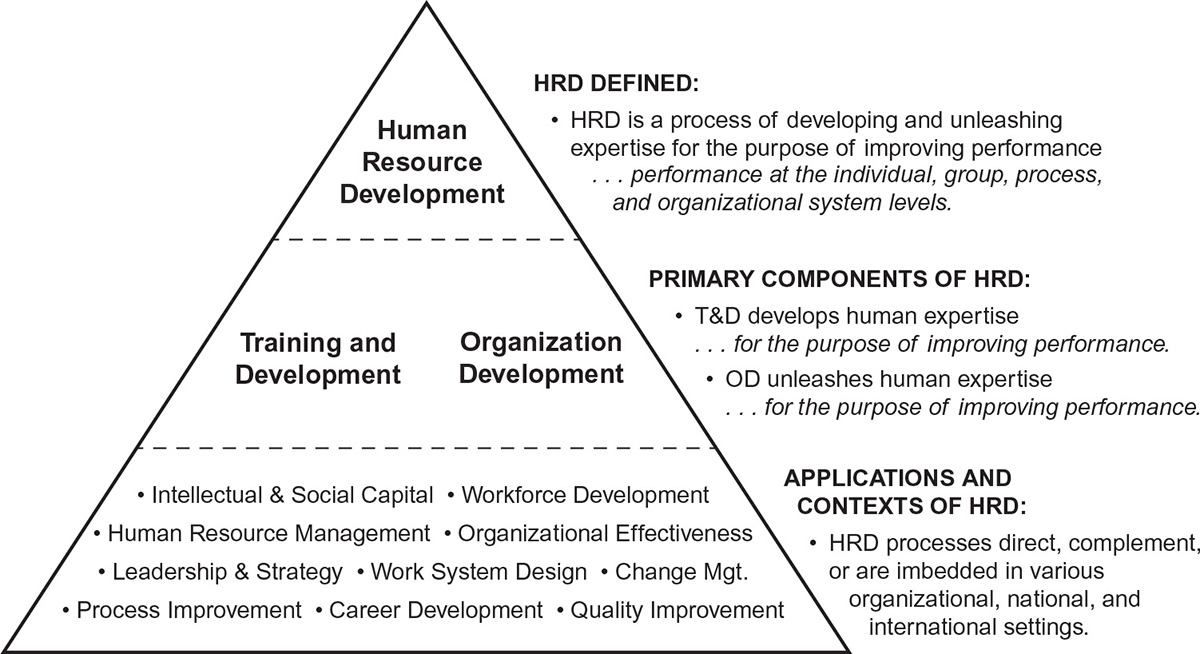

HRD efforts typically take place under the banners of “training and development” and “organization development,” as well as numerous other titles. Figure 1.1 illustrates the definition and scope of HRD in such realms as performance improvement, organizational learning, career development, and management/leadership development.

Figure 1.1: Human Resource Development: Definitions, Components, Applications, and Contexts

Source: Swanson, 2008a.

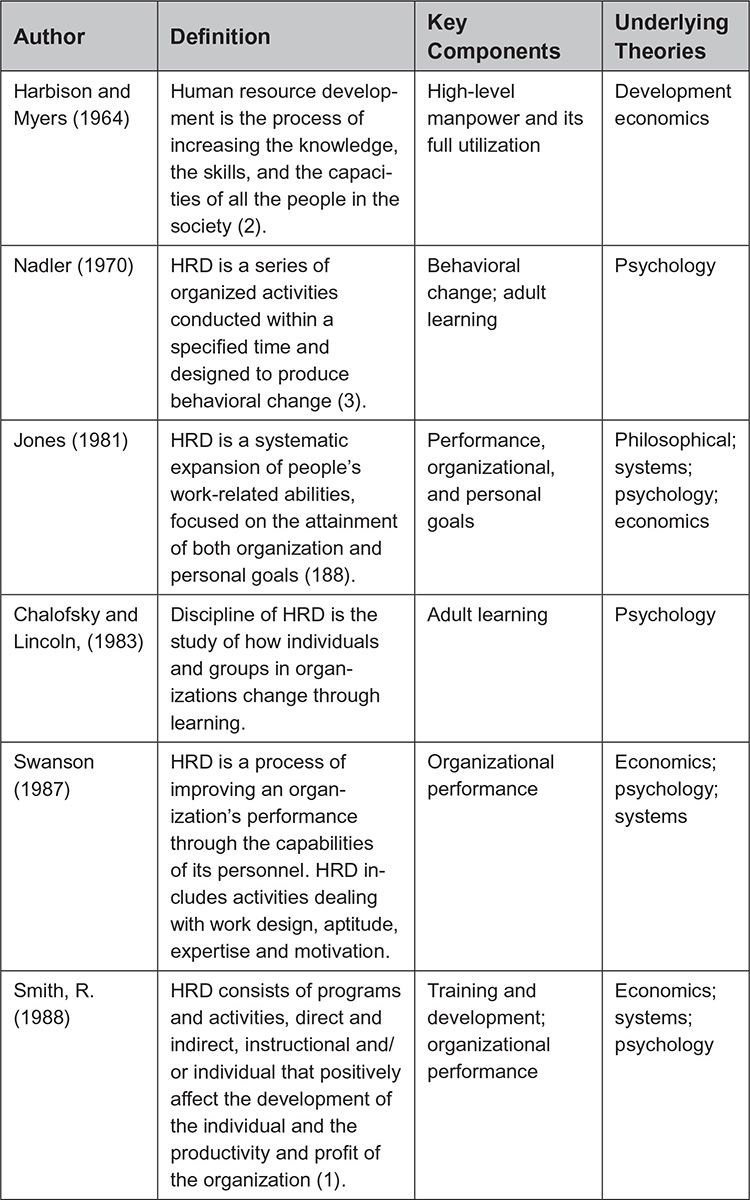

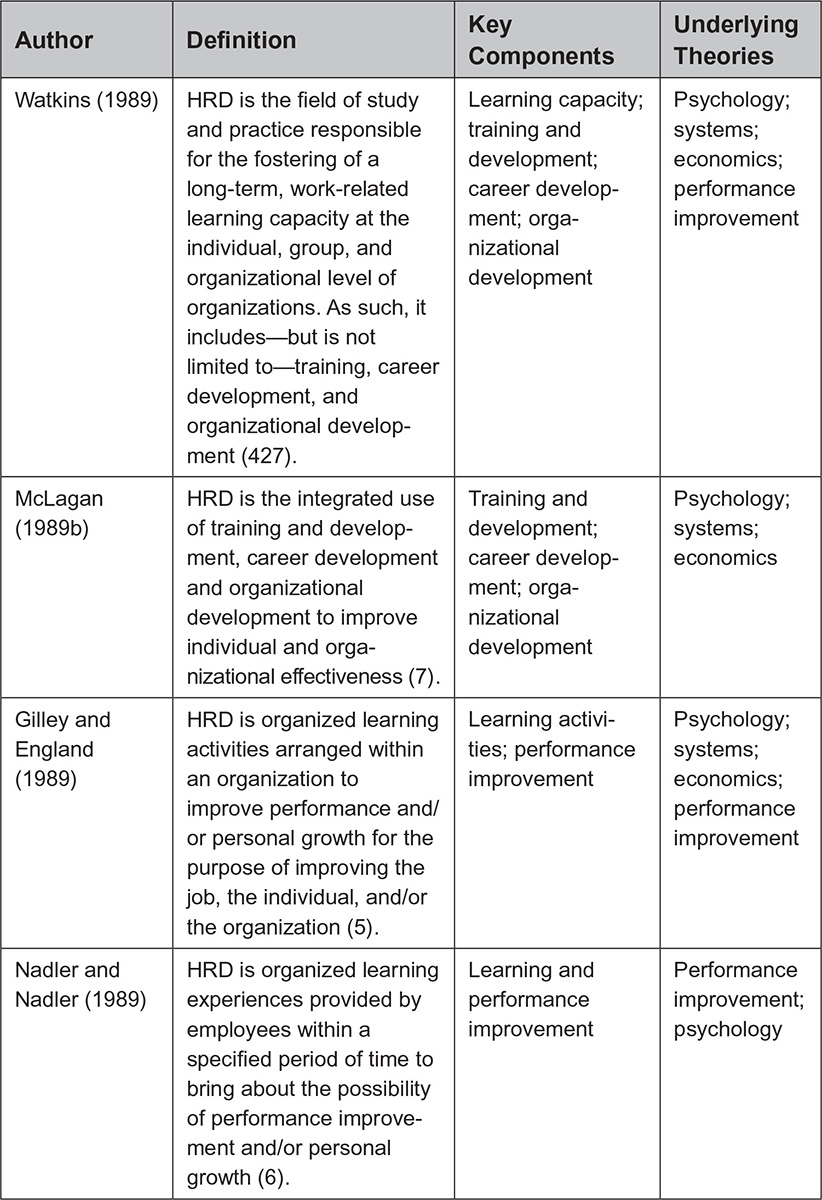

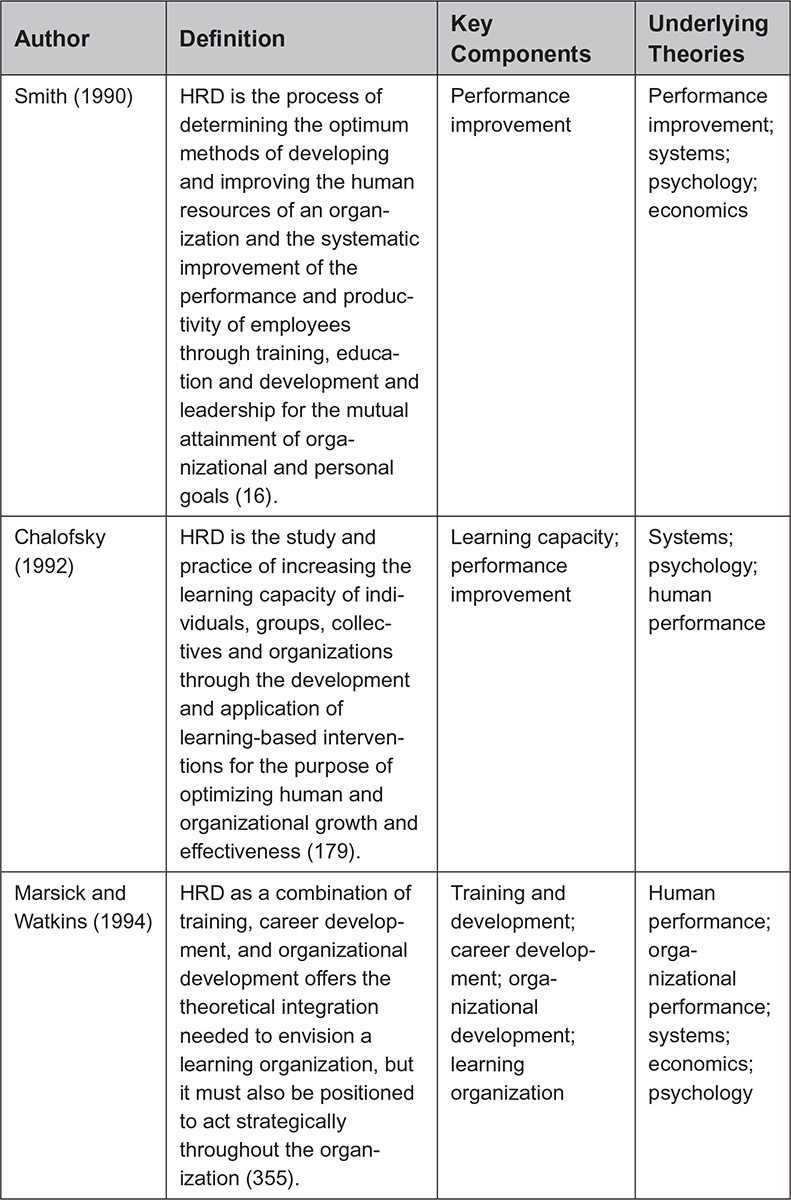

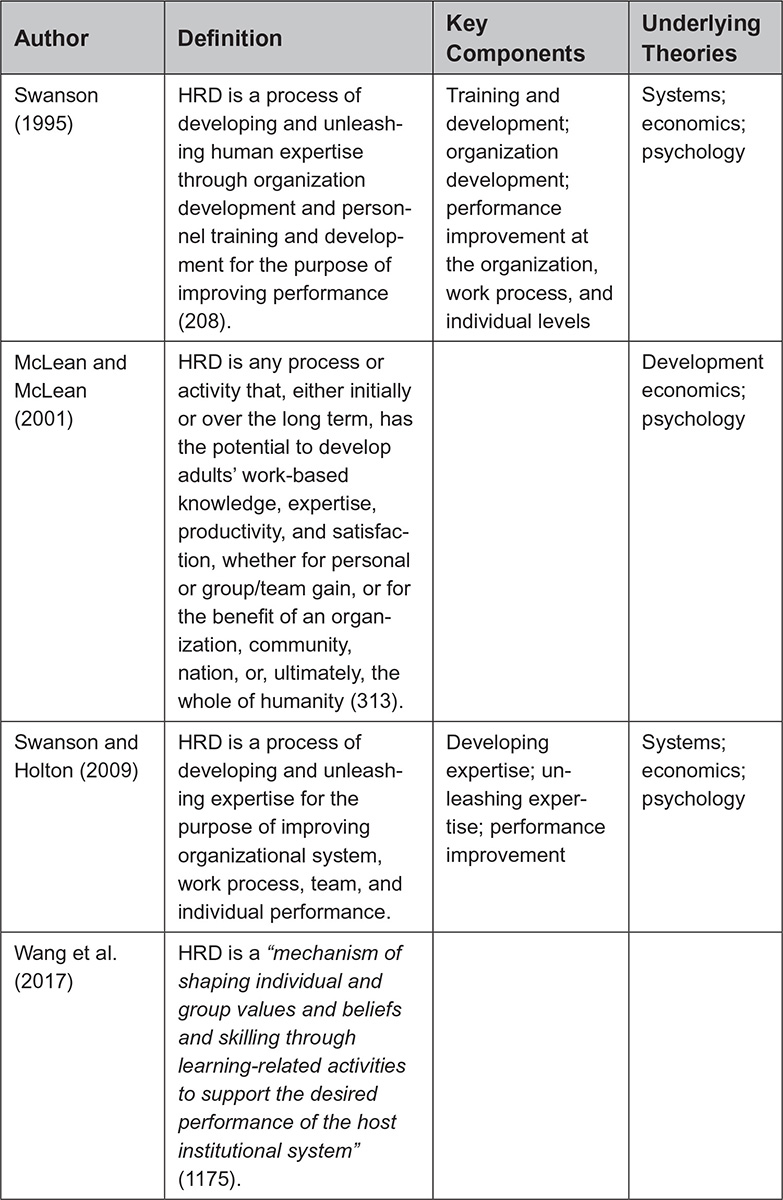

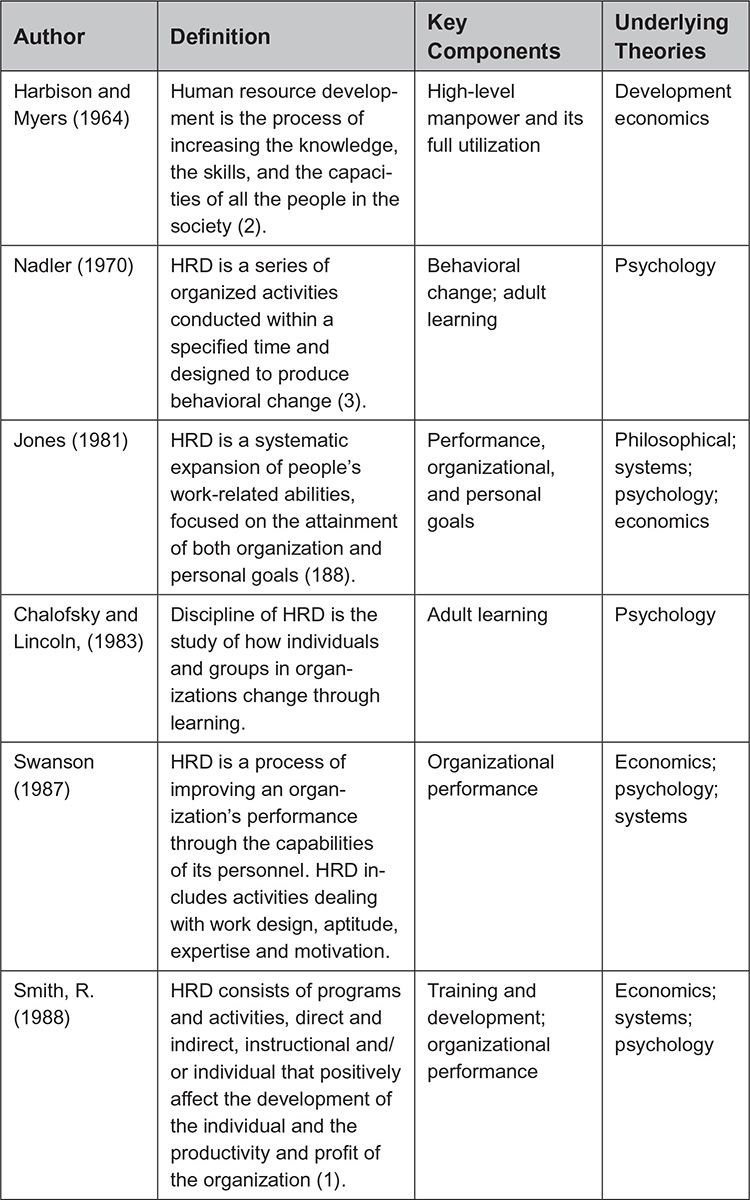

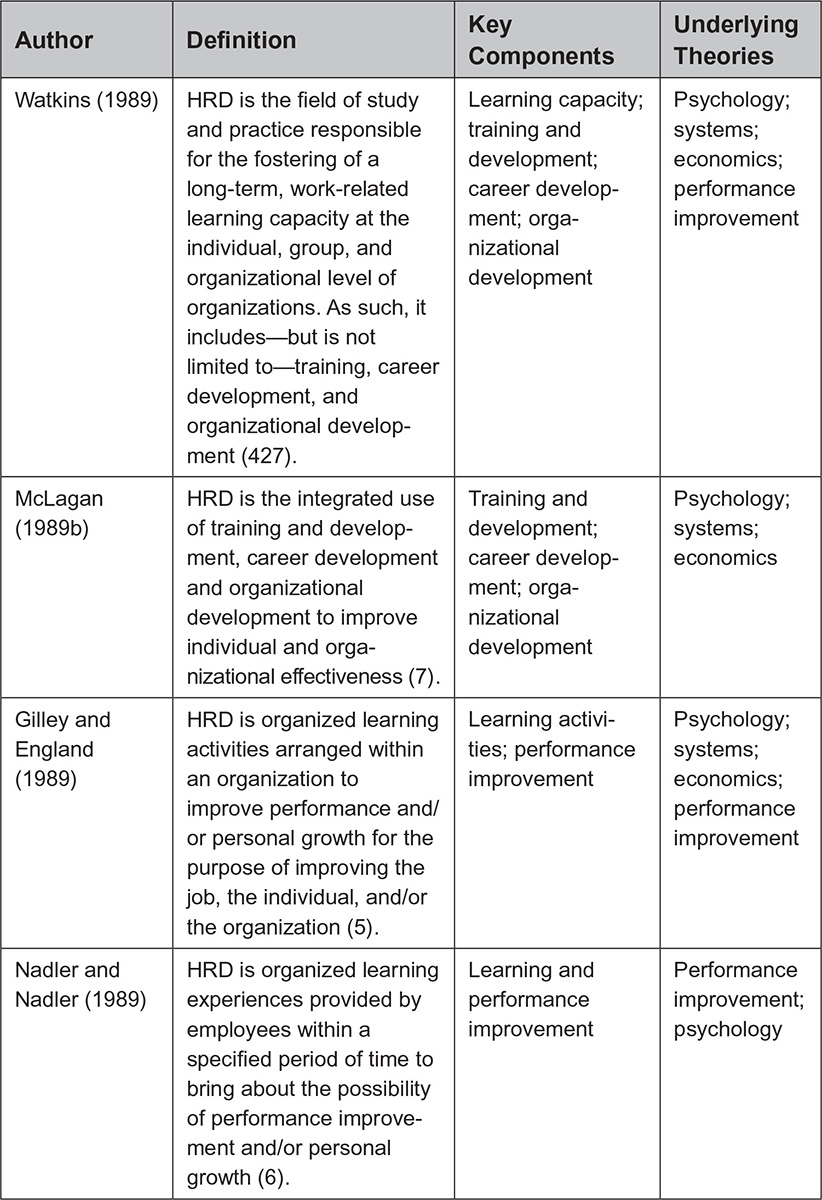

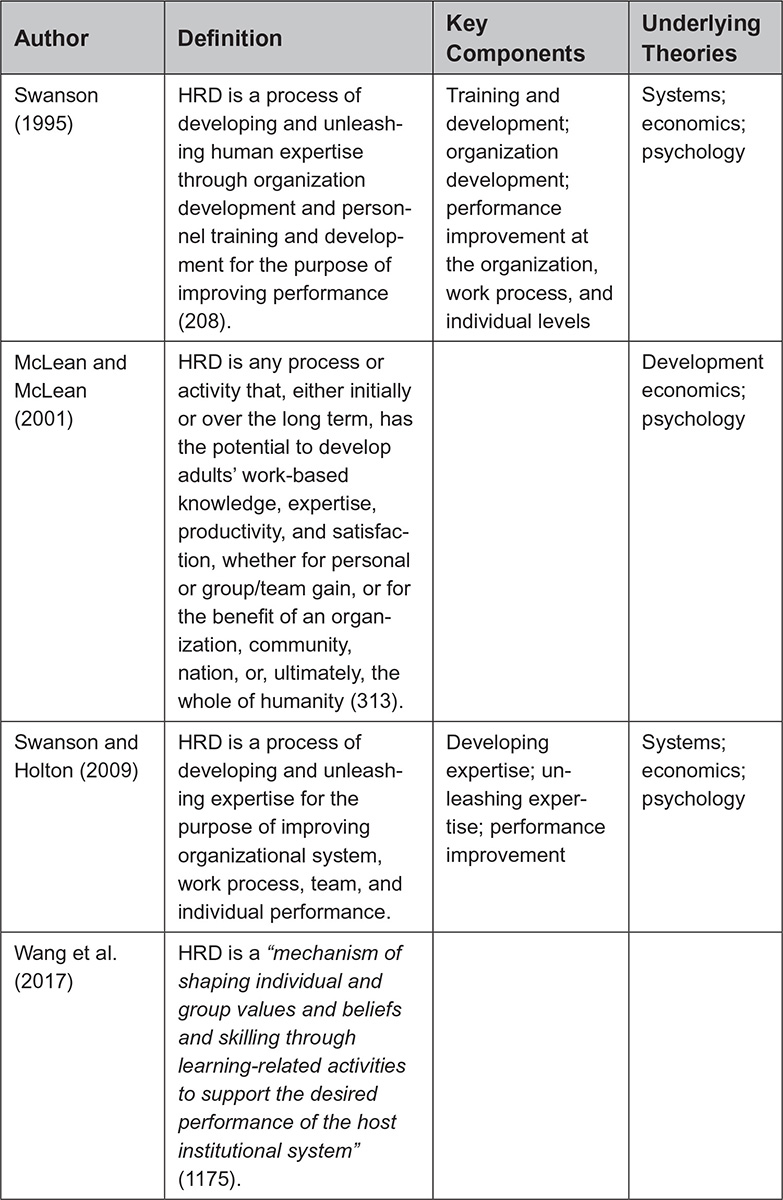

The alternative definitions of HRD that have been presented over the years mark the boundaries of the profession. Figure 1.2 provides a historical report of the range of HRD definitions found in the literature.

You can think of HRD in more than one way. Our preferred definition describes HRD as a process. Using the process perspective, HRD can be thought of as both a system and a journey. This perspective does not inform us as to who does HRD or where it resides in the organization. At the definitional level, it is helpful to think about HRD as a process open to engaging different people at different times and located in other places inside and outside the host organization.

Another way to talk about HRD is to refer to it as a department, function, and job. It can be thought of as an HRD department or division in a particular organization with people working as HRD directors, managers, specialists, and so forth. Furthermore, these people work in HRD centers, training rooms, retreat centers, corporate universities, government agencies, and online. HRD can also be identified in terms of the context and content it supports—for example, training and organization development in insurance sales. Even under these departments, function, job, and physical space titles, HRD can also be defined as a process.

Two major realms of practice take place within HRD. One is organization development (OD); the other is training and development (T&D). As their names imply, OD focuses at the organization level and connects with individuals, while T&D focuses on individuals and connects with the organization. The HRD literature regularly presents a broad variety of case studies from practice. See the accompanying examples of T&D and OD practice (page 10).

Origins of HRD

It is easy to logically connect the origins of HRD to the history of humankind and the training/learning required to survive and advance. While HRD is a relatively new term, training—the largest component of HRD—can be tracked back through the evolution of the human race. Chapter 3, on HRD’s history, provides a long-range view of the profession. For now, it is important to recognize that contemporary HRD originated in the massive development effort that took place in the United States during World War II. Under the name of the “Training within Industry” project (Dooley, 1945a), this massive development effort gave birth to (1) systematic performance-based training, (2) improvement of work processes, and (3) the improvement of human relations in the workplace—birth of contemporary HRD, as it began being called in the 1970s.

HRD Context

HRD almost always functions within the context of a host organization. The organization can be a corporation, business, industry, government agency, or nonprofit organization—large or small. The host organization is a system with mission-driven goals and outputs. In an international context, the host organization for HRD can be a nation (McLean, 2004). Strategic investment in HRD at this level can range from maintaining high-level national workforce competitiveness to fundamentally elevating a nation out of poverty and disarray.

Figure 1.2: Human Resource Development Definitions over Time

Source: Adapted from Weinburger, 1998.

CASE EXAMPLE: TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT FOR NEW TECHNOLOGY

Plant modernization and technology implementation are strategies corporations use for productivity and quality improvement. Such efforts typically have parallel T&D efforts in planning and carrying out such changes. Midwest Steel Corporation, for example, utilized systematically developed structured training instead of an abbreviated vendor-provided overview presentation. The consequences were too significant for Midwest Steel to be so casual about installing of the new steelmaking technology. The T&D staff carried out a detailed analysis of the expertise required to operate the new ladle preheaters. This analysis served as the basis for the training program development, delivery, and evaluation of operator expertise. Furthermore, following the implementation of the T&D program, a cost-benefit analysis that compared production gains to training costs demonstrated a short-term 135 percent return on investment. Continued use of the structured training program resulted in even higher financial returns for the corporation (Martelli, 1998; Cullen, Sisson, and Swanson, 1976).

CASE EXAMPLE: ORGANIZATION DEVELOPMENT FOR A GROWING COMPANY

A young and quickly growing company found itself working with systems and expertise inadequate for its present volume of business. The problems of creating and improving work systems were tackled head-on by using an organization development consultant. The consultant engaged employee groups in the following five-phase process: (1) building a new foundation, (2) high-involvement strategic planning, (3) assessment of people systems and technical systems, (4) implementing the new organization design, and (5) reflection, assessment, and next steps. The combination of learning, team planning and decision making, and employee involvement in implementing changes proved successful in advancing the company and creating a sense of employee ownership (Hardt, 1998). A more recent OD transformation initiative carried out by Accenture, a large multinational consulting firm, for one of their major clients yielded a 353 percent return-on-investment (Vanthourmout, 2008). Focusing on positive results is Accenture’s major marketing approach.

The host organization may also be a multinational or global organization with operations in many continents and many nations. Complex host organizations can both affect the structure of HRD and be the focus of HRD challenges. HRD has traditionally been sensitive to culture within an organization and between organizations. Thus, making the transition to global issues has been relatively easy for HRD.

HRD can be thought of as a subsystem that functions within the more extensive host system to advance, support, harmonize, and at times lead the host system. Take, for example, a company that produces and sells computers. Responsible HRD would be ever-vigilant to this primary focus of the computer company and see itself as supporting, shaping, or leading the various elements of the complex organizational system in which it functions. The following chapters will have much more to say about this contextual reality of HRD. For now, it is important to think about the significant variations in how HRD fits into any one organization and the variety of organizations that exist in society. This complexity is compounded by the cultural variations in which HRD functions from region to region and nation to nation. Some find this milieu baffling; for others it is an interesting and exciting aspect of the profession! For those who find HRD puzzling and those new to the profession, acquiring a solid orientation to the theory and practice of HRD as presented in this book will prove a sound investment.

HRD Core Beliefs

HRD professionals, functioning as individuals or work groups, rarely reveal their core beliefs. This is not to say that they do not have core beliefs. The reality is that most HRD professionals are busy, action-oriented people who have not taken the time to articulate their beliefs. Yet, almost all decisions and actions on the part of HRD professionals are fundamentally influenced by subconscious core beliefs.

The idea of core beliefs is discussed in many places throughout this book. To describe what motivates and frames the HRD profession, here is one set of HRD core beliefs and a brief interpretation of each.

1. Organizations are human-made entities that rely on human expertise to establish and achieve their goals. This belief acknowledges that organizations are changeable and vulnerable. Organizations have been created by humankind and can soar or crumble, and HRD is intricately connected to the fate of its host organization.

2. Human expertise is developed and maximized through HRD processes. It should be applied for the mutual long-term and/or short-term benefits of the sponsoring organization and the individuals involved. HRD professionals have powerful tools available to get others to think, accept, and act. The ethical concern is that these tools can be used for negative, harmful, or exploitative purposes (Wang, Doty, & Yang, 2021). As a profession, HRD seeks positive ends and fairness.

3. HRD professionals are advocates of individual/group, work process, and organizational integrity. HRD professionals typically have a privileged position of accessing information that transcends the boundaries and levels of individuals, groups, work processes, and the organization. Access to rich information and the ability to see things that others may not also carry a responsibility. At times harmony is required, while at other times the blunt truth is required.

Gilley and Maycunich have set forth a set of principles to guide the profession. These principles can also be interpreted as a set of core beliefs. They contend that effective HRD practice does the following:

1. Integrates eclectic theoretical disciplines

2. Is based on satisfying stakeholder needs and expectations

3. Is responsive but responsible

4. Uses evaluation as a continuous improvement process

5. Is designed to improve organization effectiveness

6. Relies on relationship mapping to enhance operational efficiency

7. Is linked to the organization’s strategic business goals and objectives

8. Is based on partnerships

9. Is results-oriented

10. Assumes credibility as essential

11. Utilizes strategic planning to help the organization integrate vision, mission, strategy, and practice

12. Relies on the analysis process to identify priorities

13. Is based on purposeful and meaningful measurement

14. Promotes diversity and equity in the workplace (Gilley and Maycunich, 2000, 79–99)

Most sets of principles are based on core beliefs that may or may not be made explicit. The pressure for stating principles of practice is greater than for expressing overarching beliefs. Both have a place, however, and deserve serious attention by the profession.

HRD as a Discipline and a Professional Field of Practice

The HRD profession and its components are large and widely recognized. As with any applied field that exists in a large number and variety of organizations, HRD can take on a variety of names and roles. This can be confusing to those outside the profession and sometimes be confusing to those within the profession. This variation is not bad. This book, and HRD, embrace the thinking that underlies these variations:

• Training

• Training and development

• Employee development

• Technical training

• Management development

• Executive and leadership development

• Human performance technology

• Performance improvement

• Organization development

• Career development

• Scenario planning

• Organizational learning

• Change management

• Coaching

HRD overlaps with the theory and practice underlying other closely linked domains, including the following:

• Workforce planning

• Organizational and process effectiveness

• Quality improvement

• Strategic organizational planning

• Human resource management (HRM)

• Human resources (HR)

Probably the most apparent connection is with the organizational use of the term human resources (HR). HR can be conceived as having two major components—HRD and HRM. As an umbrella term, HR is often confused with HRM goals and activities such as hiring, compensation, and compliance issues. Even when HRD and HRM are managed under the HR title, their relative foci tend to be fairly discrete and keyed to the terms development versus management.

Conclusion

The practice of HRD is dominated by positive intentions for improving the expertise of individuals, teams, work processes, and the overall organization. Most observers suggest that HRD evokes common-sense thinking and actions. This perspective has both positive and negative consequences. One positive consequence is the ease with which people are willing to contribute and participate in HRD processes. One negative consequence is that many people working in the field—both short-term and long-term—have little more than common sense to rely on for their efforts. Having said this, we are reminded of the adage that “there is nothing common about common sense” (Deming, 1993, 58). Common sense is the superficial assessment called face validity in the measurement and assessment profession. Something can appear valid but be dead wrong, while something can appear invalid and yet be right. For excellence in HRD, common sense is not enough.

The ultimate goal of this book is to reveal the underlying thinking and evidence supporting the HRD profession, its processes, and its tools. Thus, allowing HRD professionals to confidently accept and apply theories and tools that work while at the same time ridding themselves of frivolous and invalid theories and practices. Foundational HRD theory and practice are the focus of this book.

Reflection Questions

1. Identify a definition of HRD presented in this chapter (see figure 1.2) that makes the most sense to you and explain why.

2. Identify a definition of HRD presented in this chapter (see figure 1.2) that makes the least sense to you and explain why.

3. Of the three HRD core beliefs presented in this chapter, which one is closest to your views, and why?

4. Based on the ideas presented in this chapter, what is it about HRD that interests you the most?

Online Resources. Instructional support materials for this chapter can be found on this website: www.texbookresources.net