Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

From Conflict to Courage

How to Stop Avoiding and Start Leading

Marlene Chism (Author)

Publication date: 05/03/2022

Unresolved workplace conflict wastes time, increases stress, and negatively affects business outcomes. But conflict isn't the problem, mismanagement is.

Leaders unintentionally mismanage conflict when they fall into patterns of what Marlene Chism calls “the Three As:” aggression, avoidance, and appeasing. “These coping mechanisms are ways human beings avoid the emotions that come with conflict, but in the end it's all avoidance,” says Chism. In this book she shows how to fearlessly deal with conflict head-on by expanding your conflict capacity.

Conflict capacity is a combination of three elements. The foundation is the Inner Game—the leader's self-awareness, values, discernment, and emotional integrity. The Outer Game is the skills, tools, and communication techniques built on that foundation. Finally, there's Culture—the visible and invisible structures around you that can encourage or discourage conflict.

Chism offers exercises, examples, and expert guidance on developing all three elements. Leaders will discover techniques to increase leadership clarity, identify obstacles, and reduce resistance. They'll develop powerful skills for dealing with high-conflict people and for initiating, engaging in, and staying with difficult conversations.

Readers will learn that when they see conflict as a teacher, courageously face it, and continually work on transforming themselves, they can get the resolution they are seeking. They can change minds.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Unresolved workplace conflict wastes time, increases stress, and negatively affects business outcomes. But conflict isn't the problem, mismanagement is.

Leaders unintentionally mismanage conflict when they fall into patterns of what Marlene Chism calls “the Three As:” aggression, avoidance, and appeasing. “These coping mechanisms are ways human beings avoid the emotions that come with conflict, but in the end it's all avoidance,” says Chism. In this book she shows how to fearlessly deal with conflict head-on by expanding your conflict capacity.

Conflict capacity is a combination of three elements. The foundation is the Inner Game—the leader's self-awareness, values, discernment, and emotional integrity. The Outer Game is the skills, tools, and communication techniques built on that foundation. Finally, there's Culture—the visible and invisible structures around you that can encourage or discourage conflict.

Chism offers exercises, examples, and expert guidance on developing all three elements. Leaders will discover techniques to increase leadership clarity, identify obstacles, and reduce resistance. They'll develop powerful skills for dealing with high-conflict people and for initiating, engaging in, and staying with difficult conversations.

Readers will learn that when they see conflict as a teacher, courageously face it, and continually work on transforming themselves, they can get the resolution they are seeking. They can change minds.

1

Conflict Capacity: Comfort Is Not a Requirement

Skills development that doesn’t lead to embodiment is just a notch above entertainment.

My tolerance for certain types of personalities was limited when I first started working for myself. I found it difficult to be around know-it-all aggressive types—those who are extremely resistant and argumentative. When they became confrontational, I either avoided or became passive-aggressive. I didn’t mean to, but I couldn’t seem to help myself. Once I got triggered, my sarcasm, quick wit, or eye-rolling seemed to manifest out of thin air. This was a vicious emotional cycle of anger, regret, and aggression. I didn’t want negative people to bring me down. My justifications seemed reasonable. I’d say, “Business doesn’t have to be this difficult” and “It’s for my own peace of mind.”

I studied the effects of negativity, and I justified eliminating negative people from my life. But something kept eating at me. I believed in personal responsibility. I believed we’re all responsible for our experience. I believed Eleanor Roosevelt—“No one can make you feel anything without your agreement”—and all the other motivational quotes you hear on TED talks and Instagram. And even though I believed in personal responsibility, secretly I blamed them (negative people, complainers, high-conflict individuals) for being who they were. My real conflict was internal: my divided mind. To be honest, I wanted them to change. I didn’t want to change myself. If she could just accept things instead of complaining. If he would listen better. If he wasn’t so rude. If they were a little more self-aware.

There are a lot of misunderstandings when it comes to managing conflict and keeping peace. When we say, “I don’t tolerate drama” and “I keep negative people completely out of my life,” we are in essence saying that by controlling outer circumstances and avoiding certain types of people, everything will be fine. I’m now convinced that these beliefs are an incomplete way of understanding conflict and our ability to expand enough to truly manage and resolve conflict. To manage conflict effectively, we need to redefine conflict, recognize our dysfunctional patterns, and then work on expanding our conflict capacity. Let’s get started.

The First Way We Mismanage Conflict

The first way we mismanage conflict is how we view and define conflict. We make conflict personal; then our brains look for evidence to support our views. Most of us view conflict as some version of win-lose, right versus wrong, us versus them, liberal versus conservative. Sound familiar? All you have to do is go to social media during an election year and you’ll be reminded of how mismanaged conflict can escalate and contribute to personal loss. The dictionary definitions won’t encourage you either: A state of open prolonged fighting. A fight or a disagreement. A state of disagreement or disharmony between persons or ideas; a clash. A battle or war.1 No wonder most of us have such an aversion to conflict.

What definition of conflict would be more helpful for building conflict capacity? What if you defined conflict in such a way that you no longer had to worry about who’s to blame or think of the other as an enemy? What if you could view conflict in such a way as to be able to initiate difficult conversations that get results? Would that be more valuable to you? You bet it would. Redefining conflict in a way that took all the emotional and mental pain away would help you to build conflict capacity so that, as a result, you would be a better leader, a better partner, and a better friend.

Let me share a mental model that has significantly helped me, and I hope it helps you too. My definition of conflict is to view conflict as misalignment due to opposing drives, desires, and demands. This definition takes personality out of the equation, eliminates your assumptions about motive, and makes conflict much more interesting. Think of two arrows going in opposite directions (see figure 1).

The arrows represent the opposing drives, desires, and demands between two people or—surprise—even within yourself, with no one around to argue at all. Should I, or shouldn’t I? If I do this, then I might miss out on that. I’m not sure. Yes, I’ve decided . . . no, I haven’t. If you’ve ever stayed on the hamster wheel of indecision, you understand the cost to your mental health of not having clarity and alignment. The point here is that conflict is a misalignment that happens because there are opposing drives, desires, and demands.

FIGURE 1. Conflict

When two business unit managers argue over budget, it’s not because they’re bad people; it’s because they haven’t found ways to align their opposing desires, drives, and demands, and they can’t align until they have a conversation and seek to understand. Nor can they collaborate or compromise when all the elements within the conflict are yet to be uncovered. It’s not necessarily conflicts that ruin relationships. It’s the emotions and behaviors that emerge from a response to mismanaged conflict: disrespect, discounting, and dismissing. Think about the conflicts you’ve had. Did you give the other person the benefit of the doubt? Did you get curious as to why they saw things the way they did? Or did you immediately see them as an enemy and assume ulterior motives? Were you willing to change your own position, or were you absolutely certain you were right? If you were offended, did you take it upon yourself to humiliate someone in public, or did you use discernment and address the issue when you were self-regulated? I’m sure you can guess how most people will answer those questions, myself included. Part of the equation is self-management, and we’ll talk about that in chapter 4. Be patient with yourself and others as you try on new ideas about conflict and experiment with new methods to manage it.

Remember this: disagreement doesn’t ruin relationships; disrespect does. So, we must build conflict capacity so that we learn how to disagree without disrespecting.

Expanding Conflict Capacity

Expanding conflict capacity is about the ability to stay engaged in a difficult conversation, stay present to a high-conflict personality, and build enough self-awareness to create space or set a boundary before getting triggered into old dysfunctional patterns. Just like expanding your physical capabilities such as aerobic capacity, strength, or stamina, building conflict capacity requires conditioning, discipline, and deliberate practice, which enables you to withstand the storms instead of avoiding, appeasing, or aggression.

Building conflict capacity requires you to give up what has made you comfortable up to this point. When it comes to building conflict capacity, comfort is not a requirement. In fact, the biggest barrier to building conflict capacity (outside of cultural influences) is the commitment to comfort. When it comes to building capacity, you must be willing to recognize dysfunctional patterns within yourself. This is extremely uncomfortable. The benefit is once you recognize your own dysfunctional behaviors, you’ll be fully equipped to recognize them in the organization.

Recognizing Dysfunctional Patterns

The ability to spot dysfunctional patterns inside your organization can help you pinpoint mismanagement that’s leading to the organizational problems. In short, just because you think you understand the problem doesn’t mean you understand the cause of the problem.

I sat across from an executive team of a private practice medical clinic at lunch as we talked about all the poor performers who weren’t measuring up. When I asked for names, behaviors, and specifics, no one on the executive team could say specifically who, or what was happening. Since the defined problem was “directors who needed to be micromanaged, which resulted in wasted executive time,” I suggested we start measuring the amount of time executives spent on managing what their directors should be managing. The CEO didn’t like that idea. He said, “We don’t want people to think we are nitpicking.”

“They won’t even know we’re measuring it. It’s just to get a baseline to see how much time executives are spending doing the directors’ jobs,” I reassured him. He abruptly changed the subject and summoned the waiter to bring the bill. From my perspective, this is an example of a huge blind spot—avoiding that which is difficult to talk about today without realizing the future consequences. In an organization, the problems you can identify are problems you can fix, and the problems you misidentify equal continued frustration. Mismanagement happens when we don’t know how to define the real problem or when we avoid it because we don’t want to nitpick, hurt feelings, or seem like a micromanager.

A former client who worked as an HR leader in a large healthcare organization wrote to me when she realized the detrimental effects of avoiding conflict.

I’m just about at the end of a yearlong process of managing a disruptive employee. This situation ended up with lawyers involved and should reach a settlement today. It’s been a long and painful process, as this employee had been tolerated for 18 years. This employee was occasionally talked to, but since she was considered a “high performer,” she was allowed to carry on, hurting patients, families, and staff along the way, as well as creating chaos in her wake of disruption. The entire process has taken a toll on me, my team, and the employee. I didn’t realize how hard emotionally and mentally it would really be.

It’s difficult to learn the lessons of avoidance because the pain usually doesn’t happen immediately. There’s always a lag time between the avoidance, the justification, and the result.

Three Dysfunctional Behaviors

The three dysfunctional behaviors that leaders use to avoid discomfort are avoidance, appeasing, and aggression. Avoiders say “We’re all adults” and “I shouldn’t have to tell them.” Appeasers justify high-conflict behavior because “they are a high performer” or “they have seniority.” Aggressors retaliate and say “I didn’t ask you to work here. Find another job.”

Some leaders put off (avoid) difficult conversations because they’re afraid of their own aggression, they don’t want to make someone cry, or they view themselves as a “nice leader.”

Yelling at an employee (aggression) won’t improve their performance or build trust, but some leaders do it anyway. The release of anger feels good in the moment and dissipates some of the discomfort.

We tell a high-driving salesman we’ll consider the product next year (appeasing) to get him off the phone. We tell people what they want to hear instead of engaging in a tiring conversation where they might pick an argument.

When you think about it, it’s all avoidance . . . the avoidance of feelings, the avoidance of furthering the conversation, the avoidance of personal responsibility, and the avoidance of personal growth. The purpose of avoidance is to escape discomfort, or in the case of aggression, it’s a way to release the buildup of discomfort. Let’s look at avoidance in its purest form, and then I’ll address appeasing and aggression.

Avoiding

Some leaders know they avoid and readily admit they hate conflict. The rest of us don’t realize how much we chose comfort over accountability. Case in point: Are you eager to step on the scale after a weekend of binge eating? Me neither. But the point is, the facts are what they are, whether you know it or not. If you have a nonperforming salesman who isn’t making rain, you can avoid having an accountability conversation. In that case you’re choosing comfort before growth for yourself and the nonperformer.

If there’s a bully employee in your department, you may deny it, but the bully is still creating toxicity that’s about to explode—whether you know it or not. Ask yourself this: Am I walking on eggshells to avoid the bully? Are you avoiding because they are a good performer otherwise? Figuring out why you aren’t addressing the issue is half the battle. Looking to the future is a great motivator. What happens if you keep avoiding? Choosing small comforts in this moment often means accepting crisis in the future.

A big excuse managers have for not having a conversation is “I already know what they’re going to say.” The fact is, they don’t know because the conversation hasn’t yet been had. What they do know is their past experiences, but when we make these assumptions, we’re choosing a past experience over a future possibility. This habit of “already knowing” is costly to our personal and professional growth. You have to stop focusing on your past and focus forward for your growth. You owe it to yourself, to your employee, and to your organization. Denial and justifications only make things worse in the long run. You’re going to have to climb Mud Hill someday, and it might as well be today.

Appeasing

The distinction between avoiding and appeasing is subtle: when you avoid, employees are in the dark. They can’t tell if you’ve forgotten or if you’re just afraid to have the conversation. When you appease, employees might think you’re nice, or they think you agree when you don’t; they think you’re interested when you’re not. Appeasing is telling someone what they want to hear to get the issue off your plate. If you’re a “people person,” it feels good to see their eyes sparkle when you tell them something they want to hear. In the end, appeasing erodes trust. How many times has your own boss said something like “Good idea! I’ll get back to you” but they never did?

Let’s explore appeasing. Suppose you disagree with a colleague, but instead of saying “I disagree” and opening up for dialogue, you say, “You have some excellent points, but I have a meeting. Let’s discuss it later.” Do you really circle back to discuss later, or is it more convenient to let it slip into the dark?

Most of us use appeasing at least some of the time—for example, when you don’t want to let someone down when they ask you to work on a project, be on a board, volunteer for a committee, or do whatever with them. You feel honored, but your insides are screaming “NOOOOO!” But—you want them to like you. You don’t have the energy for listening to them try to convince you, so you say yes. Saying yes felt good in the moment, but after the high wears off, you feel resentful and misaligned. You decide to back out later. You just have to create a little white lie that they’ll buy into: Your mother is sick. Your teenager is having a breakdown. Your car is in the shop, and you don’t want to hold up the project. “Maybe next time,” you say with feigned regret in your voice. All of these behaviors compensate for the discomfort you feel when your decisions are misaligned.

Aggression

Then there’s aggression. Aggression ranges from behaviors such as eye-rolling, the silent treatment, dirty looks, innuendos, sarcasm, telling someone off, putting someone in their place in front of others, name-calling, threats, voice-raising, fist-pounding, rage, and violence. I’ll be transparent here. I’ve had to work on eye-rolling and sarcasm, and I’ve raised my voice plenty of times. I find I’m most aggressive when I’ve been fretting about something for too long and I’ve had the conversation in my head and not with the other person. Just ask my husband. He’ll confirm.

Remember my boss that I told you about in the previous chapter? He didn’t play games, and he didn’t undermine, eye-roll, or give dirty looks. No, he was straightforward. He was rude and defensive. He seemed to take any complaint as a personal threat rather than interpreting a complaint as an employee caring about what’s going on. He used discounting remarks rather than really listening to complaints.

Aggression can be a sign that the individual has reached their capacity. They’ve probably been stewing about something for quite a while, and their emotions are boiling over. Or they’re holding grudges they haven’t resolved, or their physical needs aren’t being met and they’re exhausted, hungry, or overworked. When we’re at capacity, we use the one or two tools in our toolbox to manage conflict: shaming, intimidating, or some other tactic.

What’s interesting is that aggressive types often think they’re good at addressing conflict, much like the unseasoned managers I spoke about earlier. They say things like “The buck stops here.” What they really mean is that they know how to avoid real conversations without it being called avoidance. The point is, they’re every bit as uncomfortable with conflict as the person who avoids or appeases; they just have a different method of operation.

Once I noticed these patterns, my goal was to understand the root cause of conflict mismanagement. I used to think the pattern was due to lack of skills development. This is when I would go into an organization and provide what was requested: a workshop. The workshop would work for a while, but the patterns would creep back in, or at worst, a manager would try to course correct an employee only to be overridden by their director.

No matter what kind of training is offered, skills development alone won’t override a culture where senior leaders override their managers’ decision-making. Top leaders sometimes think they need to micromanage because their managers are in the weeds, but there’s a reason—the culture. On the flip side, even when the culture supports accountable conversations, the lack of skills development can cause some messy course corrections. If a nice manager in a supportive culture that offers skills development simply doesn’t have the inner fortitude and courage, problems naturally seep in. So, what’s at the root of avoidance? Lack of experience, skills development, character, or personality? It’s the lack of conflict capacity.

Building Conflict Capacity

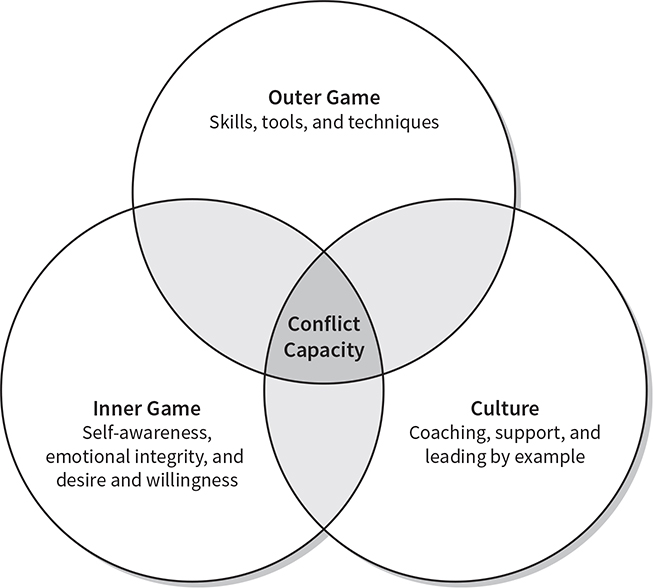

Building conflict capacity is more than skills development, temperament, experience, or possessing the right DiSC score on a personality assessment. Building conflict capacity has three distinct but overlapping elements: inner, outer, and culture. If you have only one out of the three, you won’t be very effective; two out of three can be beneficial; but when you have all three, you’ll excel at dealing with conflict. Think of a Venn diagram with three circles overlapping (see figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Venn diagram of conflict capacity

The inner game is about clarity, alignment, and decision-making, the foundation of which includes self-awareness, self-regulation, emotional integrity, desire, intention, and willingness.

The outer game is about skills development and results made manifest through tools, techniques, and deliberate practice.

The culture is about senior leaders leading by example, policies that reinforce desired behaviors, alignment to a stated set of values. This is followed by a commitment to leadership development with coaching and support to make the behaviors stick, followed by accountable conversations when they don’t.

The sweet spot of conflict capacity is when all three circles overlap and where you are building an expansive capacity for managing and overcoming conflict. Without all three, you will experience wasted time and lowered productivity, not to mention the anxiety and mental drama that comes from knowing there’s something more but not knowing how to achieve it. Let’s talk first about winning the inner game.

The Inner Game

Winning the inner game requires resolving inner conflict before trying to course correct a person or a situation. That’s because the first conflict is the inner conflict—misalignment. Misalignment happens when you have a divided mind, when beliefs don’t match behaviors, and when you don’t have the clarity to make the best decisions. You think the conflict is about the tardy employee or the aggressive coworker or the unreasonable senior leader. You want them to change, but you don’t want to risk the relationship by having what might be a difficult conversation. You can’t afford to lose them even if they are mediocre. They’re the only one who knows this part of the job. They’re going through a rough patch. You have valid reasons for avoiding the conversation. In addition, you’re a leader who cares. If you didn’t care, there wouldn’t even be a conflict at all. You’d have the conversation. You’d move on. You’d ignore it. You’d compensate. You’d fire someone. You’d leave. You’d speak up. And you wouldn’t be all that concerned about what happened, but good leaders care on many levels. We care about our career, and we’re afraid to say something to jeopardize it. We care about how we come off to the employee when we have to have a difficult conversation. We care about what people think. We care about the consequences of speaking up, and we care about the consequences of not speaking up. We care about our sense of security. We care about our self-esteem and self-image. We care about being understood, and we worry about being misunderstood.

The first conflict is that you want two things at the same time that are in opposition—you’re in a state of misalignment internally. You want to have a conversation, but you don’t want to upset the employee. You want to promote the key player, but the company honors seniority first. You want to be available, but you need to close the open door before it becomes a revolving door. Wanting two things at the same time is exhausting and takes up a lot of mental energy. You feel indecisive, confused, all over the place. Here’s why: you’re indecisive because you’re misaligned, and you’re misaligned because you aren’t clear on your values, or if you are clear, you don’t know how to make distinctions that guide your decision-making. Your desires, drives, and demands are in opposition, which at the core is an internal conflict. To win the inner game, you must resolve your inner conflicts first.

Resolving Inner Conflict

Resolving inner conflict requires three things: self-awareness, a strong values system, and discernment. Let me give you an example of how these three qualities work together; then we’ll break it down.

I’m self-aware enough to know when I’m about to reach my capacity. I’ve become aware of how my physical body feels when I’m getting impatient. When I’m tired and haven’t given myself a break, I become impatient, and my behaviors are not something I like about myself. I get a little short with others, or I interrupt, or I might let out a sigh, just a little hint to hurry the other person who has become an obstacle in my mind. It’s as if I lose my capacity to care. I want what I want. But these behaviors, while they feel good in the moment, are in opposition to something I value deeply—something that makes me a good coach and a critical thinker—a skill I call “radical listening,” the ability to be present when it’s difficult. We’ll explore more about radical listening in chapters 6 and 7.

Now that we have talked about the opposing drives, desires, and demands that create inner conflict, let’s look at discernment. I’m discerning enough to tell you that my impatience has also served me many times. My sense of urgency helps me to get things done and strive for more efficiency. So then is impatience good or bad? It all depends.

The discernment comes when you ask the question: Does this serve me now? This is how you use self-awareness, values, and discernment to resolve the inner conflict and make better decisions about who you want to be in the world.

I’ve had to create several habits to manage my own sense of urgency and make distinctions about when it serves me and when it doesn’t. The icing on the cake for me is when someone thanks me for being patient. That’s when I started noticing that I had become a creative force in my own life to change from the inside out.

The inner game requires you to be in integrity with yourself. You have to admit when you’re in over your head. You need to know when you’re not capable in the moment so that you can set a boundary or an appropriate time to become fully present. Once you tell yourself the truth, you can be in integrity with others.

How to Improve Your Inner Game

Notice how energy processes through your body. For example, when you get angry, what happens? Does your neck get hot, or does your heart rate increase? Next, notice your thoughts. What are you telling yourself about your anger? Are you blaming the other person? Are you ashamed of yourself because you think anger is wrong? Awareness of your body is one of the first steps to getting honest about what you’re experiencing, but you have to be discerning. What’s causing your reactions? Could it be something else you’re unaware of?

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention a pattern I’ve seen: a belief that their anger, impatience, and negativity is a character defect that can be overcome by trying to become a “better person.” Believe me, I have taken that journey and it’s a long and winding dark road. What works is to increase awareness of your physiological needs. For example, it’s a lot easier to be a “better person” if your needs are met and you’re well fed and well rested. Recently, I purchased an Oura ring, which gives me information about my sleep patterns and any problems of getting enough deep sleep and rapid eye movement to clean out the brain and make me more effective. I can tell you how much of a “better person” I am when I don’t eat too late, when I go to bed at the same time and have excellent recovery. As leaders we’re also responsible for our energy systems and our health because being healthy in mind, body, and spirit makes us better decision-makers, more-critical thinkers, and ultimately better leaders. Get whatever technology, tools, and other support you need to become the best version of yourself. Knowledge used is power. Here are three steps to increase your emotional integrity:

Step 1: For one day, set a timer to go off every hour for the entire day. Stop and take a breath, and then be still and mentally scan your body. No multitasking, no talking on the phone, and no reading emails. Take two minutes for yourself. Notice your heart rate, your shoulders, your neck, and your stomach. Notice your breathing. Is it fast, slow, shallow, or deep? Are you thirsty or hungry? Are you holding tension? Shift your posture, and reset your clock. Keep doing this for the rest of the day. Then, repeat again tomorrow. Get good at knowing your physical self.

Step 2: Name one pattern you have that you’d like to change—for example, impatience, appeasing, or sarcasm. What happens that triggers you into a defensive or avoidant stance? If you can name it, you can change it. Make a commitment to stop blaming the other person, and instead just notice what trips your trigger. Awareness is always the first step. You aren’t trying to change yourself or change them. You aren’t judging yourself. You are just observing. Your goal is just to notice what rubs you wrong. It might be when someone interrupts. It might be tardiness. It might be when someone is condescending. Now, name that pattern you have and what triggers your behavior.

Step 3: Ask yourself, Is this serving me now? This exercise is likely to make you uncomfortable. It won’t feel like you are doing enough to matter. It will feel more like personal development than real leadership development. Your brain will tell you all kinds of things like “I don’t have time for this” or “This is just silly.” That’s just a sign that you have work to do. Self-awareness work is hard work. Winning the inner game requires a desire to learn, more than a desire to be comfortable. You have to show up for yourself first before you show up for others. You desire to learn so much that you’re willing to look in the mirror and know your strengths and weaknesses.

Evidence You’re Improving

Here’s the evidence of improvement: First, you’ll notice your feelings and behaviors after the fact. Next, you’ll catch yourself during the act, even though you can’t control it. Finally, you see the trigger before it happens, and it’s like slow motion. There’s enough space to make a change.

The tendency for most of us is to judge ourselves for not being enough. I certainly have had enough self-judgment to last a lifetime, but I find it more helpful just to admit when I’m hungry, tired, or simply needing a break. I’m prouder of myself when I tell myself the truth about my capabilities instead of trying to push past when there’s no more gas left in the tank. Telling yourself the truth is required. You can only be as honest as your level of self-awareness, and I guarantee if you deceive yourself on a regular basis, you deceive others even if it’s unintentional. Winning the inner game is about cleaning up the inside first before helping or controlling other people. Most of what we do to avoid conflict is simply a means to stay comfortable, and when it comes to building conflict capacity, comfort is not a requirement.

The Outer Game

The second part of building conflict capacity is what I call the outer game. As I said, the outer game is about skills development and results you get due to techniques and tools that you deliberately practice. You can take a skills development course in listening and you’ll learn intellectually some methods to become a better listener; however, if you don’t have enough emotional integrity, stamina, and self-awareness to actually practice and embody the new skill, you’ll have knowledge but not the behavior. That’s where coaching comes in to create accountability for practicing the new skills, but this is the exception rather than the rule.

Most people start with the outer game. They take a communication skills course and call it a day. Those who really make the most of their self-directed learning continue to practice until they notice a shift in their own behaviors and thinking. The most useful practice is to work on these skills with a group of like-minded, growth-oriented peers where you can get support and mentor each other. The reason I started by describing the inner game is because skills development without self-awareness, discernment, and practice will go only so far. You’ll get book knowledge but not the behavior. Behaviors come from the grind of deliberate practice to change the old, ingrained patterns that connected in your brain a long time ago and worked for you until now.

Some of the skills leaders need to learn include listening, redirecting nonproductive conversations, overcoming resistance, uncovering objections, coaching to empowerment, setting boundaries, and having accountability conversations, to name a few. Most of these skills are offered in this book. In the end, it’s not about the skills, it’s about the results the skills give you, so let’s talk about results here and skills later in chapter 7. Every leader needs to know how to get these results:

Focus everyone in the same direction.

Focus everyone in the same direction.

Clarify objectives and outcomes.

Clarify objectives and outcomes.

Course correct inappropriate behavior.

Course correct inappropriate behavior.

Coach employees to improved performance.

Coach employees to improved performance.

Navigate change and uncertainty.

Navigate change and uncertainty.

De-escalate arguments and petty grievances.

De-escalate arguments and petty grievances.

The bottom line is that skills serve the purpose of improving the organizational outcomes, whether it’s increasing sales, improving productivity, reducing costs, improving collaboration, elevating morale, or simply making the workplace a better place to work, thus retaining employees and growing the business. Skills development that doesn’t lead to embodiment is just a notch above entertainment. I’m often quoted for saying “Get a clown and a pizza and it will save you more money.” Real skill development needs to be an investment in people and in outcomes. Unless someone is ultra-self-directed, real skill development usually requires more than a virtual training or a live workshop; it requires coaching groups, mentoring, measurable behavior change, and accountability.

The Culture

“Culture” is a buzz word overly used in leadership conversations, the definition of which is rarely agreed upon or understood. Some say culture is a set of beliefs that govern behavior. Others see culture as “the way we do things around here.” To introduce a greater understanding about culture, I’ll share this definition given to me (during a phone call) with the top thought leader on culture, Dr. Edgar Schein, who said, “Culture is what a group learns as its way of surviving and both getting along internally and solving its problems externally. Culture is formed by external and internal forces. What’s often missing from discussions about culture is the understanding of how the external environment influences culture.” We will talk more about the environment in chapter 5, but let’s take a peek at the external and internal forces within each culture.

External and Internal Forces

Think about what happened around the world when an external and invisible force known as the COVID-19 pandemic changed the ways we thought about work and eventually the way in which we work across the entire globe. Businesses that viewed themselves as brick and mortar allowed their employees to work from home, when it would have been unimaginable before this outside environmental influence. An invisible virus became the outside force that changed the culture of work. To survive, businesses had to innovate. Restaurants had to figure out how to turn parking lots into outdoor seating.

From a global perspective, the pandemic influenced values and behaviors. To survive, people started wearing masks, social distancing, and practicing extreme hygiene. Grocery stores ran out of toilet paper and hand sanitizers as people placed high value on what was in the past viewed as a mundane necessity. The increased demand for toilet paper, masks, and sanitizers gave some businesses more opportunity due entirely to outside influences, not because of their own marketing, their own collaboration, or their own teamwork. Other high-touch businesses like hotels, dance studios, concerts, and massage therapists shut down, not because of the lack of teamwork, poor marketing strategies, or inexperience, but because of outside influences that were outside of their control. And because of the uncertainty about when things would finally get back to normal, combined with lack of trust in experts and the media, major conflicts erupted between friends of opposing political and social orientations.

Fear and uncertainty always affect the culture, whether it’s the culture of a small business, an enterprise, a community, a nation, or the entire globe. So, what does this have to do with conflict capacity and leadership? There will always be unforeseen forces that affect culture, but leaders have a measure of control over the inner environment, and they can develop skills to ensure the organization survives.

The culture (what we do to get along and survive on the inside) must be a fit for a new leader, no matter what their title or role. The culture as well as the environmental influences of a particular organization and industry at large are about how leaders at the top view and respond to conflict. For example, if executives avoid bad news and difficult conversations, don’t expect the newly promoted director to right the ship. They won’t be supported, and as a result, the new leader learns quickly to align with the example in front of them. If managers aren’t making decisions, it could be cultural: they’re following examples at the top, or their past decisions have been overridden to keep peace. Some cultures can be very dysfunctional, yet during low-stress times, everything works well. They get along because they avoid looking at any bad news, or they promote only family members to leadership positions, whether they have the skills or not, but change, as an outside force, shifts the culture from one that worked to one that is teetering on chaos.

I’ve seen family-owned businesses that had been operating for over thirty years and the owners didn’t have a good understanding of the financials, weren’t up to date technologically, and had never gotten around to creating a policy manual or creating standard operating procedures. They relied on the good nature and loyalty of their workers, never giving them a raise and getting them to work overtime because of the “friendly culture.” Eventually, when owners desire to leave the business, they hire an outsider to right the ship and get the business ready to sell. There’s a lot less getting along and a lot more conflict between the employees, who feel betrayed. In these instances, the owners don’t really understand their own culture, the external environment, or change management.

What You Can Do Now

Look at both the internal and external factors that shape your culture. What do you have control over, and where must you adapt? Being able to explain this to your employees can help you to create better collaboration, rather than feeling like it’s all up to you or that your powers are unlimited. Next, do an inventory on your inner game. Where do you have work to do? For most of us, it’s about learning how to build space between stimulus and response and to get out of avoiding, appeasing, or aggression. The outer game is about practice until you get perfect. The next time you get caught off guard, don’t appease and don’t get aggressive. Instead, say something like, “You’ve caught me off guard and at a bad time. I’m interested to hear more, but I need to set a date for Thursday at two.” Then get the conversation on the calendar, and prepare yourself so that you have the capacity to handle the emotions. Always set boundaries when the conversation escalates. You can always start over when you’ve had rest and time to think. It gets easier with time, but when you’re learning, don’t allow yourself to be caught off guard. Take charge of your time and mental energy.

Conflict capacity includes the awareness to know you’ve hit your limit mentally and emotionally. To build conflict capacity, practice expanding your tolerance for uncertainty or discomfort while skillfully navigating the complexities of conflict. In summary, the inner game is the self-awareness, values, and discernment that enable you to withstand the storm. The outer game is skill sets, deliberate practice, and accountability. The culture includes the internal and external influences that inform how people work together. Leaders get the best results when the culture intersects with their inner game and outer game.

Reflection

1. What is your default pattern when faced with conflict?

2. What triggers conflict in you?

3. How does your organization’s culture support you as a leader?

4. What skill do you need to become more conflict capable?