Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Leadership Toolkit for Asians

The Definitive Resource Guide for Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling

Jane Hyun (Author)

Publication date: 04/30/2024

How can Asian Americans lead and influence in a way that feels culturally authentic?

19 years after her groundbreaking book, global leadership strategist Jane Hyun unveils Leadership Toolkit for Asians a guide for Asian Americans to build their capacity to lead and influence with a blueprint that is achievable and culturally relevant.

Asian Americans are the least likely demographic to be promoted or to have a mentor or sponsor they make up 13% of the professional workforce, but less than 3% of executive positions. This dynamic hurts everyone, and the solution calls us to embrace our unique perspectives while organizations create a more fertile environment for growing Asian talent.

This toolkit-based on Hyun's work with thousands of leaders-is filled with self-assessments, checklists, quizzes, and stories of Asian American leaders to help you put ideas into action. It will show you how to leverage your life experiences to craft a bespoke leadership journey.

- Assess: Identify your goals, cultural values and assets

- Equip: Navigate effectively with people who are different from you, push back against stereotypes, strengthen your networks, apply a developmental model to help you get there

- Transform: Create your own model and engage advocates as you put it into practice

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

How can Asian Americans lead and influence in a way that feels culturally authentic?

19 years after her groundbreaking book, global leadership strategist Jane Hyun unveils Leadership Toolkit for Asians a guide for Asian Americans to build their capacity to lead and influence with a blueprint that is achievable and culturally relevant.

Asian Americans are the least likely demographic to be promoted or to have a mentor or sponsor they make up 13% of the professional workforce, but less than 3% of executive positions. This dynamic hurts everyone, and the solution calls us to embrace our unique perspectives while organizations create a more fertile environment for growing Asian talent.

This toolkit-based on Hyun's work with thousands of leaders-is filled with self-assessments, checklists, quizzes, and stories of Asian American leaders to help you put ideas into action. It will show you how to leverage your life experiences to craft a bespoke leadership journey.

- Assess: Identify your goals, cultural values and assets

- Equip: Navigate effectively with people who are different from you, push back against stereotypes, strengthen your networks, apply a developmental model to help you get there

- Transform: Create your own model and engage advocates as you put it into practice

Jane Hyun is an executive coach, leadership strategist, and internationally renowned expert in cross-cultural effectiveness, leader onboarding and development. Her work helps organizations who seek to leverage the power of diverse teams to drive competitive value. She is a sought-out speaker on the topics of leadership, cultural fluency, and authenticity. Jane is the author of the groundbreaking book, Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling. Her insights have been featured on CNN, CNBC, NPR, Harvard Business Review (HBR) Working Knowledge, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, Fast Company, Leader to Leader, Fortune and Forbes.

1 THE BAMBOO CEILING AND YOU

What You Need to Know Now

Why This Book and Why Now?

“I don’t worry about my Asian population here,” said a diversity officer at a major global financial services firm a few years ago. “We’re doing pretty well with them.”

She looked so relaxed and sounded so self-assured as she spoke those words. She had approached me after I’d presented my findings at a Chief Diversity Officer leadership conference. I still remember feeling a nagging discomfort as we talked; I was disturbed that she felt she didn’t need to address an entire population anymore. Based on my work over the last twenty years with dozens of Fortune 500 companies to close the gaps for their Asian workers, I begged to differ.

The truth is that Asian Americans face multiple barriers that keep them from leadership positions, but it’s not a matter of not having the leadership skills in the first place. Instead, they might just lead differently. If a company doesn’t know how to see that potential and nurture their development, then it’s leaving unrealized value on the table.

Fast-forward to mid-March 2020. With a sinking feeling in my gut, I watched the news as America went into lockdown. I was sitting at the gate at the Minneapolis airport at the time, getting ready to board my flight, when I looked up and saw “China virus” flash across the CNN screen. Already, there were rumblings that Covid-19 was spreading. I knew that it was only a matter of time before the blame and anger toward Asians grew.

I was right. In the months that followed, there was a significant uptick in violence toward Asians. Between March 2020 and the end of 2022, more than 11,500 individual incidents of hate crimes against Asian Americans were documented. Events like the Atlanta spa shooting in 2021 and the Filipino woman stomped in Times Square made national headlines, but most events were underreported or overlooked, making even these large numbers look conservative. And who could forget the chancellor of Purdue University Northwest mocking an unintelligible Asian accent during commencement? That was a painful reminder that making fun of Asians is still socially acceptable.

After I wrote Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling in 2005, I hoped that professional spaces would become easier for Asian Americans to navigate. But sadly, that has not been the case. The rise of violence toward AAPI communities has been detrimental to their mental health and sense of safety. And the “model minority myth” (the misguided notion that Asians are all successful and have overcome the barriers to success) continues to persist. When Asians are targeted with such mockery, violence, and stereotyping, it makes it even more difficult for them to navigate a workplace that might butt up against the cultural ideals they were taught growing up.

Most people have no idea that Asians regularly face overt racial discrimination, let alone that they confront inequities throughout the corporate world. The model minority myth, by implying that Asians don’t encounter discrimination and are all quite successful, often renders them invisible. This leads to fewer resources allocated for their community across organizations (including healthcare and government services), which can also make them feel like they’re not being properly supported. Recent leadership studies have shown that Asian Americans don’t feel like they belong in their workplaces, which further diminishes their mental health.

Since the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the subsequent growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, many companies have made a public vow of change, reworking their DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) policies and promising a more inclusive workplace. The increase in violence toward Asians in the past few years has been another wake-up call for organizations. But more often than not, their statements have been vague promises without clear, measurable solutions. The reality is that much work remains to be done to both improve organizational practices and equip Asian professionals with the tools to discover, define, and bring forth their distinctive leadership skills—skills that could be of great value to their employers.

While some of this work needs to be done at the higher levels, the change can start with you. But first you’ll need to understand how you’re currently showing up. Are you fully embracing your cultural differences and using them as a tool in how you lead? Or are you suppressing and assimilating in order to be accepted, without even realizing it?

In this chapter, we’ll begin by looking at your current leadership approaches. From there, I’ll provide exercises and questions to spur your creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, and guide you through a process that will help you imagine the leader you want to become. Finally, you’ll brainstorm ways to enlist your organization (your manager, sponsor, or mentor) to partner with you in your development. You provide an openness to learning and a growth mindset, and I’ll provide the tools and profiles of leaders who have tapped into deeper aspects of themselves to transform the way they work and lead.

You don’t have to be a C-level leader who manages a hundred people to benefit from the tools you’ll find here. The goal is to design and appreciate your own leadership models by delving deep into your cultural values, life experiences, and embedded approaches.

In chaotic, unpredictable times such as these, it can be hard to feel grounded. You can’t predict when and if another pandemic will occur and rock your understanding of the world. But you can commit to personal growth and develop a keen understanding of yourself and how you want to grow and foster the tools within you, so that you’re as prepared as possible for whatever life might throw your way.

By using this toolkit, you’ll be able to develop the necessary skills to become a leader who integrates all parts of themselves. But doing so will require a deeper understanding of what it means to confront the bamboo ceiling—before learning how to shatter it for good.

Understanding the Bamboo Ceiling Today

Before you can determine the next step in your leadership journey and how you’ll get there, you first need to know exactly where you are. This means having a grasp of your personal strengths, areas for improvement, and an overall snapshot of how you’re perceived in your organization. But it also means, very importantly, where you stand given the current landscape—in business and in society as a whole. With that in mind, let’s begin by reviewing the hard data that is out there for the Asian community: How are they viewed by others and what does the data reveal? How could it inform the way you advocate for your community, the mentors you seek, how you engage diversity efforts, and how you communicate your value proposition to your employers? While some of this data might be difficult or surprising to hear, it is important for you to understand. These truths inform your starting point.

Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling: Career Strategies for Asians brought the topic of Asian Americans in leadership to the diversity table and popularized the concept to a broader public audience for the first time. Back then, the Asian American population was an even smaller segment of the workforce. Since that book was released, an enormous amount of research has emerged that reinforces my initial findings. Asians are still excluded from leadership roles and are not being seen for their full contributions. This inability to make it fully through the system is a result of the organizational dynamics that keep them from being seen as leaders.

The bamboo ceiling is a combination of individual, cultural, and organizational factors that impede the career progress of Asians inside organizations. Yet it’s not just about representation or counting the number of people in senior leadership. While it certainly includes barriers that keep them from the executive suites, it goes far beyond that to include structural biases that can keep them from being seen as leadership material.

The bamboo ceiling also reinforces the underlying assumption that “ideal” leadership template emulates the behaviors of men of European heritage. While there have been female CEOs and executives from various ethnic, racial, and cultural backgrounds who have made it into the boardrooms, by and large the leadership competencies that North American companies want you to emulate tend to discourage any variation in expressions of leadership. Women and people of color continue to be penalized when they don’t “fit the mold” perfectly, while simultaneously being told that the workplace is a meritocracy so they just have to do their job well and things will fall into place.

One female executive in investment banking told me that her firm had hired a coach to help her with executive presence. She went into the meeting with an open mind. In the first session, she was asked, “Is there a philosophical reason why you don’t wear makeup?” The conversation was less about how to get her contributions to be appreciated at the firm and more about her physical appearance.

It’s important to note that while we delve into cultural challenges that affect the Asian community here, this is not a problem that can be solved solely by Asian workers. In order to make the workplace more inclusive and to bring out the best in all employees, anyone who works with Asians needs to grow in their cultural fluency as well.

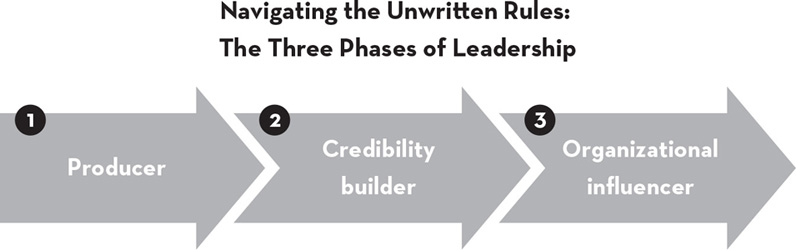

The Three Phases of Leadership

In the course of conducting research for my first book, I interviewed one hundred executives from a variety of racial and cultural backgrounds (white, Black, Hispanic, Asian) to study their stories and to understand the journey they took from entry level to senior executive. It became clear that there are three distinct phases that leaders pass through as they move from entry level to senior level: producer, credibility builder, and organizational influencer (see figure 1-1). While unwritten rules can vary from industry to industry, my team and I found that these three phases were applicable to all the industries represented by those we spoke to.

The producer stage is the first phase of your career, and you may just be starting to manage people. What your company expects of you at this stage is to be reliable at working on your deliverables and producing what you are hired to do. By the second phase, credibility builder, it becomes increasingly important that you build strong relationships across the organization. By the third phase, the expectation is that as an executive of the organization, you are an influencer across the firm or organization, and that you think and act like an owner.

As you read on, start to reflect on how this breakdown applies to you and your career. What phase are you in right now? And what do you need to practice in order to move into the next phase of development? How might you demonstrate your value in terms of the other phases?

Source: Hyun & Associates, executive insights interviews conducted by author

FIGURE 1-1. The three phases of leadership—entry level to senior level

What my team and I discovered was that it took Asian professionals the longest to move out of phase 1, often because they’re so focused on “putting their heads down” and working hard—that is, being reliable producers. Not only that, the cultural values of discipline and diligence keep them from realizing the importance of demonstrating the attributes of the next phase of leadership: building credibility. After all, you’ve probably heard the adage that you can’t wait until you get promoted to start acting like the boss.

In our work, once our clients realized that it was important to build relationships and credibility with different stakeholders, they learned to demonstrate those skills quickly. In egalitarian workplaces (such as in the United States), employees are encouraged to break out of their roles in order to maximize their potential and are rewarded for doing so (more about this in part II!). Unfortunately, many Asian executives didn’t have the wherewithal early in their careers to make those adjustments until it came out as developmental feedback in a year-end performance review or after a colleague or manager called it out.

Seven Key Findings—What Have We Learned?

Through our research of Asians in the corporate sphere, my team has discovered seven key issues that need to be addressed to fully realize the potential of Asian talent in organizations.

1) Asian Americans are far from being a model minority in corporate America, yet they’re treated as one.

Biases continue to exist for Asians, but people outside the Asian community often don’t recognize them, and even Asians can miss them. Therefore, stereotypes that are not being addressed, or are blatantly untrue, persist in the workplace and beyond. As noted earlier in the chapter, the model minority myth is the misguided perception that Asian Americans are a capable, hardworking, and docile group of people who have overcome barriers and no longer face discrimination. This has been used by the media and pundits to pit Asians against other racial groups.

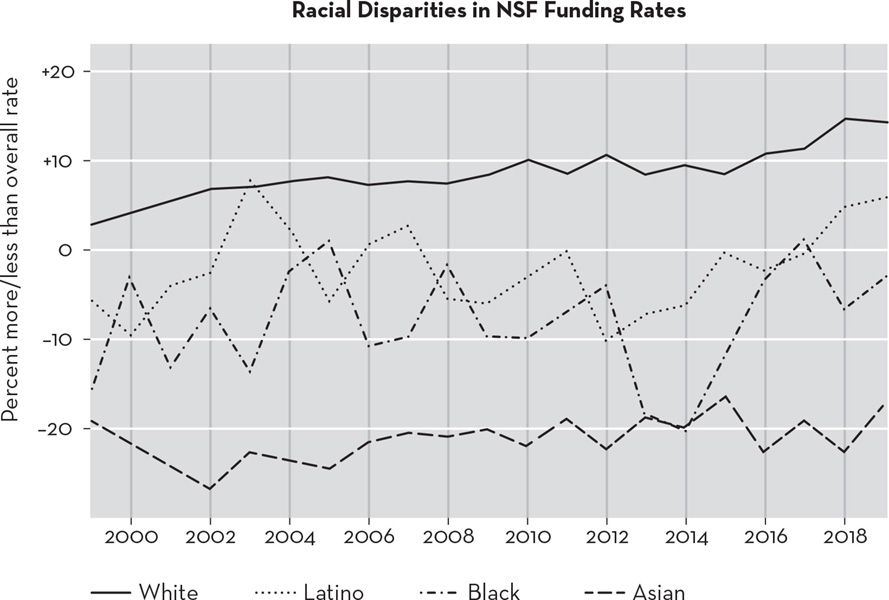

A recent study from the National Science Foundation found that Asians encounter the highest rate of rejections, challenging the stereotype that they dominate academically. In the New York Times, Christina Yifeng Chen, a geoscientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, said, “There’s this model minority myth that is a stereotype that suggests that Asians don’t experience academic challenges.” White scientists are generally more successful at winning federal research money from the National Science Foundation than Black, Latino, or other nonwhite scientists (see figure 1-2). Similarly, the success rate of proposals led by Asian scientists is about 20 percent below the overall rate—a disparity that runs counter to the narrative that Asian Americans dominate the sciences and engineering fields.

Another study by Coqual found that while 25 percent of Asian professionals experienced bias and discrimination in the workplace, only 4 percent of white professionals thought they did.

In addition, many stereotypes toward Asian Americans are seen as positive, giving the false idea that Asians excel in academics or in the sciences and therefore do not face barriers to success. But the data proves otherwise.

These disparities have, unfortunately, continued to exist, reinforcing the idea that even if there are biases toward Asians, they’re working in their favor. When Asians feel like their needs or pain points are invalidated, it is difficult for them to be fully seen in the workplace.

Source: C. Yifeng Chen, S. S. Kahanamoku, A. Tripati, R. A. Alegado, V. R. Morris, K. Andrade, and J. Hosbey, “Systemic Racial Disparities in Funding Rates at the National Science Foundation,” eLife 11, no. e83071 (2022), https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.83071.

FIGURE 1-2. Disparate success at the National Science Foundation

2) The Asian American population is not a monolith.

Asian Americans are often clumped together into one identity, when the demographics show that being Asian is an incredibly diverse and varied experience. The population comprises 23 million people, 20 countries, and even more dialects and subgroups. But because “Asian” is such a broad term, many Asian Americans feel that their individual experiences are not being recognized, particularly in the workplace, and are often confused for others.

For example, Priya, an Indian American woman in advertising, reported, “My VP often called me by the name of the Indian American woman who worked in creative. I actually work on the business side and we look nothing alike.”

The research shows this as well. A 2022 McKinsey study found that the 8.8 million Asian Americans are split across three main ethnic subgroups: East Asian, Southeast Asian, and South Asian. This wide-ranging distribution across industries and roles underscores the diversity of experiences among Asian American workers. They are overrepresented in low-paying occupations such as manicurist, skincare specialist, cook, and sewing machine operator. At the same time, they’re also overrepresented in higher-wage technical fields, such as software development and computer programming. The large variance of wages between these occupation clusters means Asian Americans have the highest income inequality in the United States. An Asian American Federation study showed that one in four Asians in New York City lives below the poverty line.

There’s a loss of identity when your boss or your client confuses you for the other Asian person in the office. You might ask yourself, Do they even know what I do? It’s painful when you feel like you don’t matter. When this dynamic is exacerbated without relief, it has a lasting impact on how engaged Asian employees are in the workplace.

3) Asian professionals operate in a very narrow band of “acceptable behaviors” in the workplace.

Many Asians feel the need to edit themselves or hide their cultural differences (including minimizing their accents and other attributes) to be perceived as effective in the workplace. A recent study, Asians in America, found that Asians were the least comfortable “being [them]selves” in the corporate workplace.

In my firsthand experience running leadership coaching programs for Asian Americans, I found that nearly half of the participants I worked with were born in Asia and still carry deeply embedded cultural values from their country of origin. Multinational companies prefer a leadership style that reflects the needs of the corporate headquarters, which are typically located in North America. If you are an applicant who might not be perceived as “aggressive” or capable of promoting your accomplishments, you will be seen as ineffective. One Chinese American lawyer was told that he needs to operate with more of an “effortless swagger” like the partners. Fitting into the corporate system can come at the cost of suppressing who you are.

Asian women experience a double dilemma: those who are extroverted or outspoken report getting feedback from managers and colleagues that they are “too aggressive,” while those who are more reserved in demeanor get penalized for “not speaking up.”

It’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

4) As a result of the increase in violence toward Asian Americans, they are experiencing increased levels of stress and mental health issues.

The 2023 Strangers at Home study, which documented the daily indignities of racism and microaggressions for Asian Americans, shows evidence of a broken career pipeline. Nearly two out of three Asian professionals said that the ongoing violence against the AAPI community has negatively impacted their mental health, and 62 percent said that it has decreased their feelings of safety while commuting to work. Additionally, 50 percent said it has diminished their ability to focus at work, and one in three Asian and Asian American professionals said they have experienced racial prejudice at their current or former companies.

My own friends have told me that they are afraid to commute on public transportation throughout the country. I have felt this fear as well. In a chaotic and uncertain time, it’s another thing to worry about when you don’t know when and if you can leave the house to run an errand, let alone report to the office. Without having this acknowledged or improved, Asians are facing a constant daily battle that is unlikely to resolve itself.

5) Asian employees are not adequately recognized by organizational diversity initiatives and are therefore underresourced.

In my own research, I found that affinity group networks that focus on Asian American employees’ needs are underresourced. Corporate leaders often have good intentions of supporting our community and might even express their commitment verbally, but they offer little funding and advocacy to make that intention a reality. I’ve even had large companies ask if I could work or speak for free. Time and time again, I’ve seen how little funding Asian resource groups get.

The Strangers at Home study backs this up. It found that while Asians are getting hired and recruiters are happy to bring them in, they’re entering a system that’s indifferent or hostile to the way that they show up, or they’re not provided with the necessary support to advance through the career lifecycle. Asian employees end up spending a great deal of effort trying to fit into the system and not bringing their authentic selves to the workplace.

6) Asians lack sponsors who could advocate for them and provide access to future opportunities.

An important discovery I’ve made while conducting leadership interventions in companies is that you can’t advance Asian talent by just “fixing the Asians.” A supportive management structure, combined with sponsors and mentors, is an absolute requirement.

However, the Strangers at Home study found that Asian and Asian American professionals are the least likely of any racial group surveyed (29 percent) to say they have role models at their company, the least likely to say they have strong networks (17 percent), and the least likely to have a sponsor (21 percent). Due to underrepresentation in senior roles, lack of role models, and thin support networks, Asians have few if any advocates in powerful positions to help their career advancement.

Many Asians lack access to exclusive networks, which keeps them from high-profile projects and “insider track” knowledge. This is also backed up by my own research. For fifteen years at Hyun & Associates, my team and I have asked Asian professionals in our leadership coaching programs if they had sponsors in their organization. We defined sponsors as senior leaders (not necessarily their direct managers) who were advocates for their careers. We distinguished the role of sponsor from mentors (who provide career advice, general support, and guidance about organizational politics). Only 15 percent of the mid-career professionals we polled had sponsors. Sponsors are influential executives who are willing to “put in one of their chips” in your favor in spaces and places where you don’t have entry. In most organizations, it is very difficult to get ahead without a sponsor. The majority of people we worked with had mentors, but not sponsors.

This created a gap in the workforce and made it increasingly difficult for Asians to rise into leadership roles. Without an influential sponsor, you will never get the access you need to gain entry to the next level of leadership.

7) Asians often feel like they don’t belong in the workplace.

The Power of Belonging study conducted by Coqual in 2020 found that Asian women, Black women, and Asian men had the lowest levels of “belonging” in their workplace. Asian women had the lowest levels of belonging when compared with all ethnic/racial groups. To better identify the building blocks of belonging, the study grouped twenty-four items that characterized belonging into these four categories:

- ● Seen: Does the organization recognize and value my contributions?

- ● Connected: Do I have positive, authentic interactions with others?

- ● Supported: Does the organization provide the support to get my work done?

- ● Proud: Do I feel aligned to the purpose of the organization, and not just like a “cog in the wheel”?

Feeling like you don’t belong can have a severe impact on your day-to-day functioning on the job and on your mental health.

This finding was supported by a 2022 Bain study called the Fabric of Belonging. The survey showed there is a critical need for greater workplace inclusivity for Asian American workers. Asian men and women feel the least included of all the demographic groups Bain surveyed. However, less than 30 percent of employees across all geographies, industries, and demographic groups say they feel fully included at work. Asian workers report feeling the least included, with only 16 percent of Asian men and 20 percent of Asian women saying they felt fully included at work.

This lack of acceptance can create a gap where Asian workers, by trying to “fit into the norms,” are wasting valuable time and energy that would be better spent on creating innovative solutions.

Accelerating the development of Asians in organizations requires these seven issues to be addressed. And it will require more than just Asians trying to develop new skills and going out of their comfort zones to work effectively. Instead of conforming to the existing models, we need to rethink and redesign what leadership competence looks like for a multicultural, global workforce. Asian American leaders bring strong language and cultural acumen that can be a hidden competitive advantage for companies looking to thrive in a diverse marketplace. Asians need a new way to express their leadership, and their colleagues and managers need a new way to see their Asian populations. We need a wide-angle lens to accommodate a variety of leadership approaches. And that’s exactly what I’ll be walking you through in this book.