Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Make It, Don't Fake It

Leading with Authenticity for Real Business Success

Sabrina Horn (Author) | Anna Crowe (Narrated by)

Publication date: 06/22/2021

Driven to succeed under constant pressure, entrepreneurs and business leaders alike can be tempted to exaggerate their strengths, minimize weaknesses, and bend the truth. Through the twin lenses of running her own national public relations firm and advising thousands of executives for a quarter-century, Sabrina Horn revisits the core of leadership; defines authentic, reality-based business integrity; and shows readers how to attain and maintain it.

With firsthand accounts of sticky situations and painful mistakes, Horn lays out workable strategies, frameworks, and mental maps to help leaders gain the clarity of thought necessary to make sound business decisions, even when there are no right answers. In her straightforward, no-nonsense style, she shares the power of humility and empathy, mentorship and self-assessment, and a strong core value system to build a leader's confidence and resilience. Horn's fake-free advice will empower readers to disarm fear, organize risk, manage setbacks and crises, deal with losing and loneliness, and create a culture and brand designed for long-term success.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Driven to succeed under constant pressure, entrepreneurs and business leaders alike can be tempted to exaggerate their strengths, minimize weaknesses, and bend the truth. Through the twin lenses of running her own national public relations firm and advising thousands of executives for a quarter-century, Sabrina Horn revisits the core of leadership; defines authentic, reality-based business integrity; and shows readers how to attain and maintain it.

With firsthand accounts of sticky situations and painful mistakes, Horn lays out workable strategies, frameworks, and mental maps to help leaders gain the clarity of thought necessary to make sound business decisions, even when there are no right answers. In her straightforward, no-nonsense style, she shares the power of humility and empathy, mentorship and self-assessment, and a strong core value system to build a leader's confidence and resilience. Horn's fake-free advice will empower readers to disarm fear, organize risk, manage setbacks and crises, deal with losing and loneliness, and create a culture and brand designed for long-term success.

CHAPTER ONE

SOME REALLY BAD ADVICE

A s this is a book about achieving business success with integrity, it is important to understand something about why people lie. It is obvious that lying should not be our modus operandi, yet it happens all the time, in various forms and for different reasons. Understanding what compels people to fabricate the truth, to fake it, and to just plain lie is useful in coming up with the strategies and tools to avoid or prevent it.

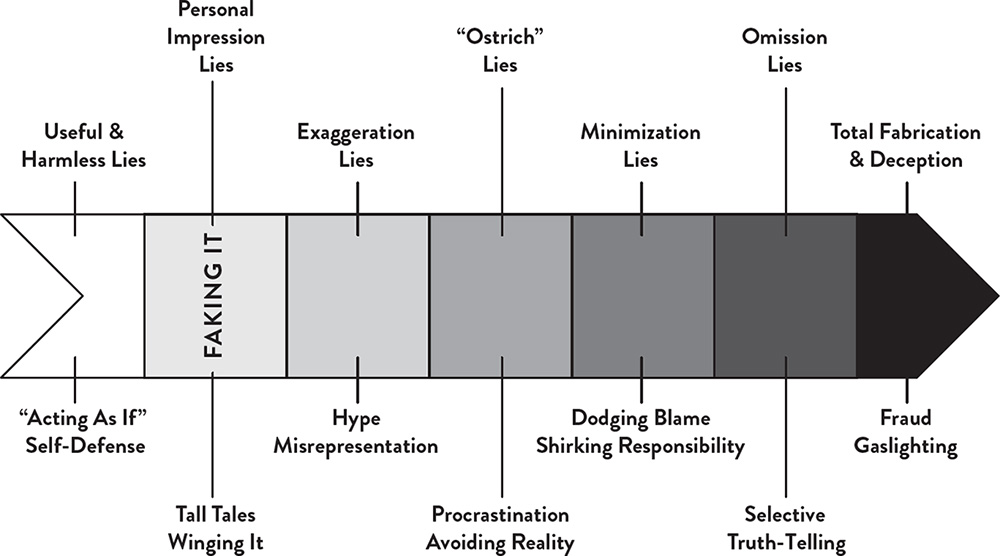

There is a broad spectrum of fakery, from the perfectly innocent—Adler’s “acting as if”—to the perfectly criminal. In what follows, I explain that continuum with examples. To help you visualize it, I offer my Fake-O-Meter (figure 1). Note that the phrase “FAKING IT” marks the point at which certain types of lies pass from relatively harmless to costing you and others time, money, and reputation.

FIGURE 1 Fake-O-Meter

THERAPEUTIC, USEFUL, AND NECESSARY LIES

Biologically, intellectually, politically, and morally, we live in an impure world. We have to make peace with that reality and navigate it as well as we can. But let’s agree from the get-go that not all lies are equally bad and that some are therapeutic, useful, or even necessary. With this in mind, we can go on to define the degree of moral impurity with which we are willing to live.

Acting As If

As we saw in the introduction, Alfred Adler’s confidence- building approach of “acting as if” is a therapeutic use of pretending (in this case a benign type of lying), with origins in psychology. You pretend—to yourself—to be more confident by acting as if you were as confident as you would like to be.

The result, Adler and others have found, is that you actually feel more confident and, feeling confident, you perform as if you were truly confident. This may lead to more successful outcomes in your interactions, which serve to further reinforce your feelings of confidence. With a bit of luck, a virtuous circle is formed, in which successful outcomes produce greater confidence, which produce more successful outcomes, and so on.

“Acting as if” can be especially useful to anyone who suffers from imposter syndrome, the strong and even debilitating feeling that you are undeserving of your achievements. Those afflicted feel that they are frauds and fear that they will be exposed for faking their way to success, when in reality they never faked it at all and earned success honestly. People who already struggle with issues of self-efficacy and perfectionism often fall victim to “imposterism.” It is actually a common disorder, affecting as many as a third of high achievers, both men and women. About 70% of adults experience it at least occasionally.1

If you are troubled by imposterism, “acting as if”— pretending how it would be if you felt that you were competent, accomplished, and deserving of praise and admiration—may help change how you feel. You can also reflect upon, assess, and appreciate your actual achievements. Inventory them, admire them, but do not compare them to the achievements of anyone else. Measure your own achievements, not those of others.

Other strategies in the “acting as if” category include “dressing for success”—for instance, wearing black or red to feel more powerful. Visualization also can be helpful when preparing to face new or potentially challenging situations, a practice I have often found helpful. I previsit the scene in my imagination as a way of rehearsing how it might unfold, thereby becoming more comfortable with how to navigate it. I call this watching myself in my own movie. The ethical common denominator in all of these forms of “acting as if” is that the pretending is strictly between you and your own imagination. No part of it is being done at the expense of another person.

But can “acting as if” cross the line from therapy to actually faking it? And can that faking be undertaken to the detriment of someone else? Absolutely.

While you cross no ethical line by faking confidence itself, you must not fake external reasons to back up your confidence. For example, you may act as if you are confident that your business proposal is a winner, but if you tell a prospect that you have the data to prove it when no such data exists, you are crossing an ethical line, and quite possibly a legal one as well.

The Little White Lie

“Little white lie” is one of those expressions that everyone believes they understand but which turns out to have a wide and remarkably vague range of meaning. Some believe a white lie is any benign, trivial, or harmless falsehood. The problem with this definition is that it leaves far too much to individual judgment; what I might consider trivial and harmless, someone else may find scandalous. Besides that, even telling trivial lies may get you busted and, therefore, branded as a liar or a fibber. Either way, people may become reluctant to trust you.

The safer definition is to think of a white lie as something you say to be polite, to avoid hurting someone’s feelings, or to avoid upsetting someone unnecessarily.

WIFE : “Does this outfit make me look fat?”

HUSBAND: “You look gorgeous in anything.”

Often, a white lie takes the form of rendering an opinion that is absolutely the most positive you can come up with. At a dinner party, your host serves a spectacularly bland meal.

HOST : “How did you like the fish?”

YOU: “I loved the delicate flavor.”

In a business context, white lies are often a disservice. Whenever a client asked me for my opinion, I told the truth, though I sometimes modulated it to be as constructive as possible within the confines of the truth. For instance, if something the client proposed was flawed, I would try to comment truthfully on what was good about it and use that positive element as a platform from which to suggest improvements. With respect to my own feelings, this was a white lie. For the purposes of making a suboptimal project better, however, it avoided demoralizing or even alienating the client while moving the project toward improvement.

Finally, white lies can reduce life’s friction from day to day. “How are you?” is among the most conventional greetings we offer one another. Sometimes, however, you have a headache, feel anxious, or didn’t get a good night’s sleep. But do you really want to get into all that? So you answer, “Just fine. And you?”

Necessary Lies

The third type of “innocent” lying in this category is necessary lies. The sudden, unexpected loss of a loved one may be met with denial or a refusal to acknowledge reality. Such evasion of facts is not immoral or unethical. Indeed, it may be an emotionally necessary or at least unavoidable initial response to the loss.

Or consider this: an EMT arriving on an accident scene begins treating a gravely injured man.

“Am I going to die?” the victim gasps.

Acting on a strictly professional assessment, the most accurate answer might well be “Yes, probably.” But the medic knows the value of hope and responds instead, “No. Hang in there. We are going to take very good care of you!”

And finally, people lie to protect their privacy and that of their family. They may lie in situations of physical danger, to save themselves or others. These are necessary lies and there is no argument there.

FAKING IT: THE BRIGHT RED LINE

It is at this point that “acting as if” and other types of lies in this category cross a threshold into faking it, because the fakery is being conducted at another person’s expense, albeit without malice. Anxious to make a good impression or to avoid making a bad one, we may tell a tall tale, twist, cover up, augment, wing it, deliberately deform, or evade the truth. A personal lack of confidence, insecurity, or a perceived inadequacy leads many of us into this kind of fakery. These types of lies are more interpersonal, simpler, and not as egregious as others we discuss later, as measured on the Fake-O-Meter.

Twisting and Evading

It was the summer before my senior year in high school and I had a job working at a popular stationery store in town. The owners, a nice elderly couple from Poland, sold magazines, chewing gum, cigars, cigarettes, baseball cards, candy, stuff like that. I often thought that maybe someday I could own a nice little store like this, too.

The thing is, they ran an open cash register business; they never shut the cash drawer to ring up a sale. It was just money in and change out. With every sale, I had to do the math in my head, even calculating the sales tax. Unfortunately, I just couldn’t add or subtract that quickly, and I was too embarrassed to ask for a pencil and paper. Using the cash register was out of the question; it would have required them to change their business model. I wanted the owners to think I was smart, like them.

It went down like this. A customer would walk up to the counter with a magazine, some gum, a pack of cigarettes, and a couple of greeting cards. I’d act like I was doing the mental arithmetic and then arrived at some random number that might be acceptable.

“Uh, sure. That’ll be eight dollars, please,” I’d say, hoping the customer’s reaction would be positive.

Maybe the figure was close. Maybe it wasn’t. In reality, it was total improv. One hundred percent.

Amazingly, it worked—for a little while. But the day of reckoning came, when the owners realized I was essentially giving their merchandise away. With admirable patience, they presented me with the pad of paper and pencil I should have asked for in the first place. It certainly was easier, writing it all down, but they stood over me and watched me like a pair of hawks. The surveillance was so unnerving, I still couldn’t add or subtract on the fly, especially when someone gave me a twenty to break on a $3.28 sale.

I did not make it at the stationery store. I was fired, and I learned my first hard lesson in the consequences of faking it. In retrospect, that lesson may not have been hard enough. Certainly, I had no intention of cheating my employers, but cheat them I certainly did. This instance of fake it till you make it was at their expense, and thus I had blithely crossed the line into petty fraud.

Tall Tales

In my twenties, I learned the fake it lesson again. This time, though, I did it for love. I wanted to impress Jeff, an entrepreneur who had his own start-up, and when the subject turned to skiing, I mentioned that I loved downhill.

“Really?” he asked.

“More than anything.”

“You any good?”

“I’m double black diamond good,” I laughed.

At this, he invited me to ski the double black diamond run at Squaw Valley, the site of the 1960 Winter Olympics, near Lake Tahoe, California. I figured, how hard could it be? Growing up on the East Coast, I had skied on sheer ice in Vermont and New Hampshire and was a decent intermediate skier.

Without skipping a beat, I accepted, and he made the arrangements.

When I got off the chairlift at the top of the mountain, I thought I was going to die. This was it; game over. Call the chopper, bring the stretcher. Eventually pulling myself together, I slid down the entire vertical drop on my side. Clearly, faking it had not worked for me. I definitely wasn’t going to make it with Jeff, either.

Winging It

Fast-forward a few years to when, as a young executive, I was sitting in front of a client who was going on and on about some new technology he wanted us to promote. Wanting to impress him, I nodded my head in bogus understanding, though I didn’t have a clue what he was talking about.

Did I pull it off? Yeah. Did I have to backtrack? Usually.

I never felt great about it, and it was kind of stressful. I should have just brought the discussion back to how we could help him from a marketing standpoint, or suggested that we do a deep dive into his technology at some other time. In the moment, I didn’t have the confidence to stop, ask a question, or redirect the conversation. It would have been so simple. But then, hindsight is the Great Simplifier.

There also were side effects I had to consider. As a leader, you are always under a microscope. If I faked it, others around me would likely follow my example. Even small acts of fakery, harmless in themselves, nurture a let’s-just-wing-it culture, which I did not want to create in my company. Sometimes in business, you do just have to wing it. That is also a reality. Yet it is the proverbial exception that proves the rule. Winging it, more often than not, is faking it and therefore is not a sustainable business practice.

EXAGGERATION LIES

Exaggeration is the false assertion that something is greater or better than it actually is. It is one of the most common ways to fake it till you make it in business today. Instances of exaggeration, their eventual exposure, and the resulting consequences range widely in severity.

A really popular example is lying on your résumé or in a job interview to appear more accomplished. In fact, a 2017 study revealed that 85% of employers caught applicants lying on résumés or applications.2 Other common examples of lying through exaggeration include inflating a product’s actual capabilities to garner more customers or to secure venture capital (VC) funding, and overstating company revenues to attain a higher valuation. At any point, the fakery can be exposed. The customers or VCs will discover that the product doesn’t do what management promised and the auditors will uncover the faulty financials. The consequences can range from losing professional credibility or a job opportunity, to losing financial support, customers, and revenue, to getting sued and, at a still-realistic extreme, facing criminal prosecution. Definitely not the right strategy to achieve success.

Hype Cycle Lies

Hype is a kind of exaggerational fakery prevalent within marketing and PR, which are all about image and perception building. It is more sophisticated and broader in scope than simply twisting the truth a little to impress a friend. I cannot begin to tell you how many times prospective clients came to us saying, “Build our buzz. Make us a hot company to watch!” If I had a nickel, as they say.

Thankfully, there are ways of building brands for companies that actually deserve to be “hot,” as you’ll see in chapter 4. The harder trick, I discovered, was helping those companies that were viable but perhaps less interesting “wannabes,” while also steering clear of the ones that thought they could use PR to be something they could never live up to. The bottom line, as I mentioned in the introduction, was always an exercise in identifying their “real” story, remaining within the boundaries of the truth while also highlighting what was genuinely most interesting, beneficial, or different. As our clients’ agents or representatives, this was as much an exercise in advising them on what not to say (“We’re going to close a huge deal next week that’s going to be a real game changer!”) as it was in communicating their true stories (“The benefits our current customers are experiencing are an indicator of early market traction.”).

Company credibility and reputation are all based on track record, on what you have achieved. They also are based on what you are accomplishing, how you conduct yourself, what you stand for and from which you never veer. That’s making it. And the only way we could make it for them—and ourselves, for that matter—was to not fake it.

Build It and They Will Come!

Now imagine that not one but all of your customers and competitors are in an industry bubble, an economic cycle marked by the rapid escalation and exaggeration of market value. As former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan put it during the 1998–2000 Internet boom, it was the era of “irrational exuberance.”

During this period, VCs funded almost any start-up boasting an online platform. Business software companies catapulted to success by creating the infrastructure for this e-commerce. New market categories were created literally overnight. Companies were swept up into the tornado of success, quickly went public or got acquired, and generated lucrative returns, many of them only on paper. It was a modern-day gold rush.

“Build it and they will come,” a phrase made popular by Kevin Costner’s 1989 movie Field of Dreams, was the mantra of the time. And everyone in the tech ecosystem wanted to be in that movie: lawyers, bankers, publicists, consultants, analysts, the media itself. My company was caught up in it, too. There weren’t enough tech PR people on the planet to support all the business we could have taken on. Prospects offered us free stock and three months’ retainer if we “saved them a slot” on our roster. Feeding into the frenzy, we decided to open a branch office in Seattle in late 2000.

That office did not last long. We built it. They did not come. End of story.

A famous example of the dot-com era is Pets.com, one of the first companies to sell pet supplies online. The company spent a great deal of money marketing a cute canine sock puppet as its public face, and it even managed to get the puppet interviewed by People magazine and Good Morning America. The company’s executives never really thought through the whole business model behind the sock puppet, however, and on November 9, 2000, it put itself to sleep. Rivals like Petopia.com, which recruited some of my employees with stock options and huge salaries, soon folded, too, along with hundreds of other companies.

The great majority of the tech execs of this era were not deliberately or criminally deceitful. Some had great ideas but no business being CEOs. Others had great leadership experience but went into the public markets too early, with no profits, incredibly high valuations, and unproven business models. Still others had technology that wasn’t quite ready for prime time.

It was a type of fakery in which substance was overlooked and blind ambition and, yes, hype and greed took over.

Pets.com and countless first-generation Web start-ups never figured out how to build real businesses. They were based on a variant of fake it till you make it called build it and they will come. They made it—for a short time—but with a flawed strategy, and they all eventually ran out of time and money.

Hot Seat Lies

Let’s look at the time when we were recovering from the Great Recession of 2008 to 2009 and my company really needed to ramp up revenue. On a sales and business development rampage, I put myself out there and led a pitch to win a half-million-dollar account, a comprehensive integrated marketing campaign for a company in the financial technology software space. This would be a huge piece of business, and winning it would really help our situation.

Did we have the skills in-house to do the work I promised?

I would find them!

Did we have the bandwidth to lead such a complicated campaign?

I’ll put my best people on it!

Can we get them a story in The Wall Street Journal? Whatever. Sure.

Exasperated and under serious pressure, we punched above our weight and faked our capabilities. Having exaggerated our capacity, we were behind the eight ball before we even started. Our recommendations were off the mark and the cofounders did not care for our delays and excuses. We made the head of marketing who hired us look bad. Bit by bit, we lost pieces of that account— until we lost it all, along with a chunk of our credibility. It sucked. I learned the lesson, and it cost me and my organization.

Overconfident and Arrogant Lies

During my career, I’ve met a lot of tech executives who were, shall we say, “overly optimistic” about the viability of their businesses. They were all trying to make it, strutting their stuff with greatly exaggerated stories of what their products could do, in the hope that we, in turn, would project that image to the press. To convey the real facts about our clients, we required that every engagement begin with an assessment of actual versus future capabilities, current installed base, and customer endorsements. We asked to see their business plans, spoke with their investors, and in some cases, even reviewed their financials. We did our best to not get caught up in their fakery.

“We are leaders in the supply chain software market and have customers around the world,” one start-up founder arrogantly told me.

I don’t think so, Mr. Founder, I said to myself. You have five other competitors, all much larger than you, zero revenues to date, and exactly three customers—to whom you gave your product for free. Also, nobody cares.

I almost took pleasure in dismantling his claims.

Once, I even met a man at a software conference who introduced himself as the CEO of a start-up and said he wanted to retain our firm to handle his PR. Terrific! Except it turned out that he was not the CEO—which was just as well, because there was no start-up, either.

There are countless stories like these, some ridiculous, others sobering, and many just pathetic. Looking back, most of the infractions were relatively innocuous. Lessons were learned, mistakes corrected, apologies offered, and people moved on.

OSTRICH LIES

In this category, the person involved may be either intentionally or unintentionally kicking problems under the rug, unduly procrastinating, or, like the stereotyped ostrich, sticking their head in the sand, all because they are so utterly overwhelmed with the situation at hand and what lies ahead.3 Sometimes the truth is that, as an entrepreneur or business leader, you simply don’t know what to do. You hope it will all go away, and you want to pretend everything is fine. This is faking it, because at the moment, you are not dealing squarely with reality.

Unfortunately, the evasion comes at everyone else’s expense. It’s extremely dangerous, because you’re at risk of waiting too long to formulate a plan of action, putting all your stakeholders and the viability of your business in jeopardy, and dragging everyone down with you.

As a young female executive running a tech PR firm, I came head to head with this.

In 2001, already in business for ten years, we had some of the top software companies in the industry as clients, a strong brand, and a good reputation. But as the Internet bubble was bursting all around us, our clients were cutting their budgets almost daily. The business I had worked so hard to build was evaporating. Being eight months pregnant with my second daughter, Christina, I had other thoughts on my mind. I wanted to pretend everything was okay and that it would all just get better.

“Hope is not a strategy, Sabrina,” one of my advisors told me. “You have to protect the financial health of your company and let some people go.”

It became abundantly clear that if I wanted to have any chance at continued success, at making it, let alone at surviving the tech bust, I would have to face reality. I had never done a layoff before, but I did it then, and it nearly destroyed me. Having to let people go whom I had hired filled me with guilt. Professionally, the layoff was a tremendous setback for the business, a loss of forward momentum, of revenue, and of the ability to serve our clients. Personally, it came at a time when I was trying to focus on having my baby. The layoff pulled me away from mindfulness of that incredible life experience.

This was one of many hard lessons I learned about real leadership. Running a successful business means making the right decisions at the right time, based on reality. It also means making those decisions for the greater good of the whole company, often in the face of great disruption and painful change. Eliminating jobs was awful, but using up all our cash reserves, potentially going bankrupt and losing everything, would have been much worse. I had to choose the lesser of two evils. I chose the former, which would prevent the latter from happening. It was the right strategic move.

MINIMIZATION LIES: SHIRKING RESPONSIBILITY AND DODGING BLAME

The opposite of the exaggeration lie is the minimization lie, which seeks to lessen the extent and consequences of a bad situation by shirking responsibility and dodging blame. Minimization lies often involve rationalization and take place when people can’t completely deny the truth.4 A well-known example is from the mid-1980s, when vacuum cleaner maker Regina changed management and brought out products that were less expensive to manufacture. The problem was that the cheaper plastic parts sometimes melted, and customer returns rose to some 16% of gross sales revenues. The new CEO cooked the books to understate the losses in advance of an audit. Eventually, the defects outpaced management’s ability to hide the losses, and the company collapsed with a loss to investors and creditors of some $40 million.5

OMISSION LIES: SELECTIVE TRUTH TELLING

Lying by omission is as common as telling white lies or fibbing, but, depending on the nature and scope of the omission, it can be grossly deceptive. Here, you are actually telling the truth, but you also are leaving out certain critically important facts, creating misconception in an effort to move something forward. For many people, omission is easier than other types of lying because it doesn’t involve making anything up and is therefore more passive.

For example, you might say, “I went to the meeting and we had a productive discussion,” while omitting the fact that part of the discussion centered on radical budget cuts. Or you might mention that you parked the car in the garage and turned off the lights, but leave out the part where you arrived home at three a.m., hit the back wall, and smashed the headlight.

In the corporate world, lies of omission can be grave indeed. Take the example of Boeing’s 737 Max aircraft, which suffered from technical problems that resulted in two deadly crashes, in 2018 and 2019, and killed 346 people. The tragedies were investigated by the US House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, which found a “lack of transparency”—in short, lying by omission—to be a major factor in the failure to correct defects that directly resulted in the accidents.6

OUTRIGHT DECEPTION: THE HIGH COST OF FAKING IT

On the continuum of faking it, there are, of course, extremes. People who shamelessly lie to manipulate other people do so on purpose to mislead and deceive for personal gain. They fail to consider others’ well-being or safety, and they intentionally lie at others’ expense, to put themselves in a better position.

Manipulative lying includes gaslighting, a form of psychological deception in which a person covertly sows seeds of doubt in a targeted individual or group, making them question their own memory, perception, or judgment. To this person, buying or even stealing success might seem more rewarding than putting in the work to earn it.

Fabrication lies are entirely untrue and made-up stories. These lies can be at least in part delusional, but most are intentional, and they often are the product of desperation.

People who lie in such deliberately deceptive ways end up depending on the people to whom they have lied in order to perpetuate the fiction. In so doing, they lose their independence and sink deeper into an ongoing pattern of compulsive lying. Take Bernie Madoff and his massive Ponzi scheme, a fraud worth nearly $65 billion. He faked it till he made it and then ventured far beyond that, into the largest financial fraud in US history. Madoff ruined thousands of lives and ultimately received a term of 150 years in federal prison. The night before his arrest, Madoff finally told the truth, announcing to his family, “It’s all just one big lie.”7

Why did he do it? In 2011, Madoff answered this question for Harvard Business School professor Eugene Soltes, who interviewed him for a study on white-collar crime: “In hindsight, when I look back, it wasn’t as if I couldn’t have said no.… It wasn’t like I was being blackmailed into doing something, or that I was afraid of getting caught doing it.… I sort of rationalized that what I was doing was OK, that it wasn’t going to hurt anybody.” Madoff added, “There was nothing that… I couldn’t attain.… I was able to convince myself that this was, you know, a temporary situation.”8

Madoff’s statement goes a long way toward explaining the fake it till you make it trap. The faker succeeds in convincing himself that his fraud is temporary, a kind of stopgap measure on the way to making it. Yet, somehow, the “making it” never arrives, and the “temporary” fraud becomes permanent. No longer a tactic, the fakery becomes a strategy—and then a business model. By embracing this, Madoff inflicted around $64.8 billion in losses on his clients.9

A second, more recent example of a big-time faker is Elizabeth Holmes, the former CEO of Theranos. After dropping out of Stanford, she started Theranos to “democratize health care” with a fully automated digital device capable of testing a variety of diseases using just a pinprick of blood. Despite the small army of experts who told her that what she proposed was virtually impossible, she was still able to persuade venture capitalists to fork over $500 million in funding. She won a lucrative and highly publicized partnership with Walgreens, as well as with other health care organizations, and was running a company valued at $9 billion in 2014.

But Holmes ran her company in secrecy and did not unveil its mysterious yet much-hyped Edison prototype device until 2015. A few insiders began leaking stories of how Edison produced wildly inaccurate blood analysis results. Reporter John Carreyrou of The Wall Street Journal investigated the leaks and published a blockbuster story that essentially blew up the company, exposing the Edison device as, quite simply, massively failed technology.10 In 2018, Holmes settled a Securities and Exchange Commission lawsuit for fraud, surrendered control of her company, and paid a half-million-dollar fine.

Why did Holmes do it? Whether she is in denial or delusional or both, she has never admitted wrongdoing and, in a 2017 deposition, said the words “I don’t know” six hundred times.11 According to Jessie Deeter, a producer of an HBO documentary on Holmes and Theranos, those who know Holmes best claim that “she really believed her own story.… She believed her own bullshit.”12 Yet she clearly faked it, made it, got caught, and lost it all. As of this writing, she is under indictment and, amid speculation about a possible insanity defense, faces up to twenty years’ imprisonment if convicted.

SIMPLY BAD ADVICE

Yes, there are big differences, both in magnitude and in motivation, between my faux math in my hometown stationery store, my skiing disaster, and my missteps as an inexperienced CEO; the irrational exuberance of tech CEOs in the late nineties; and Madoff’s and Holmes’s multiyear reigns of fraud. The degree of deception and self-deception runs from a laughable infraction to the most unthinkable of crimes. In the extreme cases, the faking it rolls on and on, even as the making it recedes deeper into a future that never arrives. Faking it becomes a way of doing business and a way of living life—at least until the truth comes out and the game ends.

Bottom line: People fake it to attain something for themselves, whether that is for good reasons or bad. In all cases (except for self-help, self-defense, or politeness), whether a short-term tactic or a permanent strategy, it is at someone else’s expense and it is never the “right” thing to do. It is never a recipe for long-term business success. It certainly is not what real leaders practice. It is simply bad advice.

REAL LEADERSHIP FOR THE REST OF US

True leaders search for what they can give; others search for what they can take. Most CEOs and business leaders locate their leadership style somewhere between these two poles. Some drift back and forth between them, often unpredictably. Still others aspire to truth in leadership but settle for a lot less. Some— some—prove to be real leaders, the kind who build their brands and lead enterprises that stand the test of time and are based on core principles of honesty, integrity, and a healthy dose of humility. That doesn’t mean they don’t make mistakes; they just make them honestly.

This book was not written for the Madoffs or Holmeses of the world. They are beyond hope. This book is for the rest of us, the entrepreneurs, business leaders, and CEOs who need to be pragmatic and are working toward a realistic promise of success. We want to grow our businesses the right way. We are well-intentioned and want to be good leaders. We face challenges every day. Some challenges are temptations to fake it, to shove a problem under the rug, or to minimize what is going on. Most are opportunities to be 100% authentic, while others demand a compromise between the fake and the real.

There is no textbook for how to deal with these situations, and there is no road map for success. It is all about the “getting there,” the journey to making it, which is what matters most in authentic leadership.

Are you equipped to face reality in a career-creating, life-defining opportunity to make your own destiny? For me, both the question and the answer took place in the fires of Dresden, Germany, many years before I was born.