1

Serving

DISCIPLINE OF SERVANT LEADERSHIP

If the thought of change instills in you the “FUD” factor—fear, uncertainty, and doubt—you’re not alone. Fear of change keeps people in relationships they’ve outgrown, jobs they don’t like, and even hairstyles that no longer suit them.

FEAR: F#©% Everything and Run

Likewise, even when organizations understand that change is necessary if they are to add value and remain competitive, they also suffer from FUD. They fear that they may fail; face uncertainty about how to change or, rather, what actions will lead to successful change; and, finally, doubt whether all the time, money, and effort it takes to implement change will be worth it.

That’s where you come in. The truth is, people don’t change their minds; they make new decisions—sometimes frequently—based on new or added information. This new and added information accelerates change by influencing decision-making in both individuals and groups.1

With that truth in mind, it becomes clear that “servant leaders” (like you) are not engaged to change peoples’ minds, but rather to make it easier for people to choose appropriate change supported with more informed decisions. By speaking with people rather than at them, servant leaders create environments that foster breakthrough solutions.

Table 1.1. Knowledge Transfer Molds the Optimal Leadership Technique

Information Storage |

Knowledge Transfer |

Leadership Technique |

Bard |

Oral |

Steward |

Book |

Print |

Manager |

Documentary |

Broadcast |

Executive |

Cloud |

Digital |

Facilitator |

In most organizations, this change begins during meetings. The problem is that meetings often fail for one of three reasons:

- The wrong people are attending (rare).

- The right people attend but are apathetic and don’t care (rarest).

- The right people care but they don’t know how to conduct an effective meeting (bazinga!).

We know that groups can make higher-quality decisions than the smartest person in the group alone, so why don’t we invest in learning how to run better meetings? Part of the problem can be found in our muscle memory. When part of a group or team, we are more attuned to taking orders than creating collaborative solutions.

Historically, leadership techniques have evolved based on where information was stored and how knowledge was shared—from rural stewards who knew about crops and animal behavior to complex urban environments layered with infrastructure and technology.

In recent centuries we relied on executives and managers for their experience and machine knowledge. As leaders, they told us what to do. Today’s complex knowledge base and knowledge transfer technique, however, requires a new breed of servant leaders. Most of them are trained to avoid problems attributable to weak meeting leadership, poor facilitation, and lack of meeting design. This new breed is not a person, but a role—the role of the meeting facilitator (see table 1.1).

From this point on, I use the following terms and understanding:

-

All servant leaders are leaders, but not all leaders are servant leaders.

- – Servant leaders accept the likelihood of more than one right answer and serve others to help them find the best answer for their own situation.

-

Early on I frequently use the term “servant leader,” because much of the material in the first four chapters applies to both servant leaders and meeting facilitators.

-

All skilled meeting facilitators are servant leaders, but not all servant leaders facilitate meetings.

- – Servant leaders may also be found as advisers, arbitrators, coaches, consultants, and ombudspersons and in other roles in which they share primary skills with meeting facilitators, such as active listening, maintaining content neutrality, observing, questioning, and seeking to understand.

- Beginning in chapter 5, I refer more frequently to the meeting designer—a title that frequently also designates the meeting leader, distinguished from the “meeting facilitator.”

-

To be precise, being a meeting leader requires managing three additional roles—meeting coordinator, meeting documenter, and meeting designer—that are quite independent of the role of meeting facilitator.

- – In a practical sense, however, people often act as meeting leaders because they usually perform all four roles, although not all the time—especially in more complicated meetings, frequently called “workshops.”

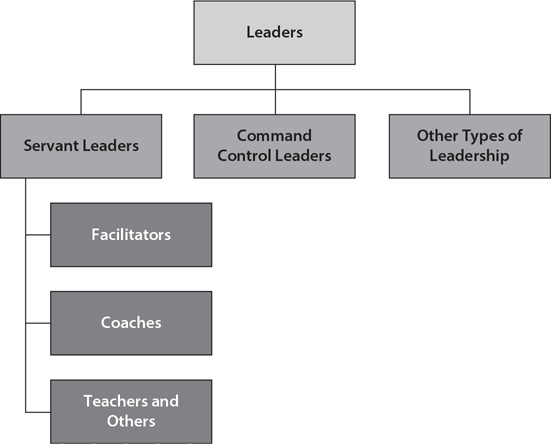

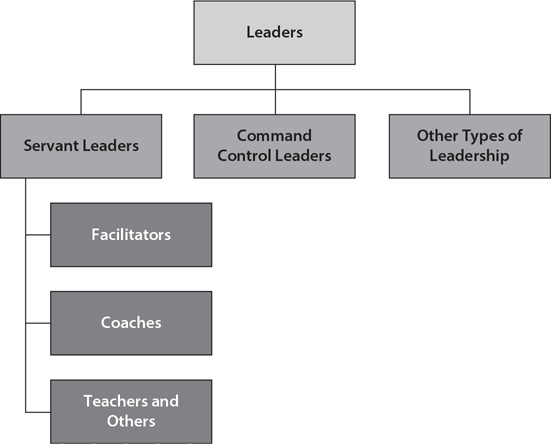

Figure 1.1. Hierarchy of Leadership

The Servant Leader Solution

As the workplace transforms, leadership techniques change. Today, instead of dealing mostly with individuals (one-on-one conversations), servant leaders work frequently with people in groups (ceremonies, events, meetings, and workshops). Instead of supervising hours of workload, servant leaders help their teams become self-managing (see figure 1.1). Instead of directing tasks, servant leaders motivate people to achieve results.

Facing consecutive days of back-to-back meetings, meeting participants value well-run meetings that focus on aligning team activities with organizational goals. Professionally trained facilitators solve communication problems in meetings or workshops by ensuring the group stays focused on the meeting objectives while applying meeting designs that lead to more informed decisions.

Compared to traditional or historic leaders, modern leaders exhibit many of these positive traits. A further shift is required, however, for many of these leaders to become truly facilitative, so that teams and groups realize the full potential of their commitment, consensus, and ownership.

Have you ever led a meeting? I’ll assume that you have. Ask yourself, What changed from the moment your participants walked into the meeting until the meeting ended?

As a servant leader and meeting facilitator, you become the change agent, someone who takes meeting participants from where they are at the beginning of the meeting to where they need to be at the conclusion. All leaders must know where they are going. They must know what the group is intending to build, decide, or leave with when the meeting is done. Effective servant leaders also start with the end in mind.

The servant leader does not have answers but rather takes command of the questions (see table 1.2). Optimal questions are scripted and properly sequenced. If you were designing a new home, for example, you would consider the foundation and structure long before you decide on the color of the grout. By responding to appropriate questions, meeting participants focus and generate their collective preferences and requirements.

A neutral meeting leader values rigorous preparation, anticipates group dynamics, and designs the meeting accordingly. The meeting leader becomes responsible for managing the entire approach—the agenda, the ground rules, the flow of conversations, and so on—but not the content developed during the meeting. Effective meetings result from building a safe and trustworthy environment, one that provides “permission to speak freely” without fear of reprisal or economic loss.

Table 1.2. Characteristics of the Facilitative Leadership Difference

Modern Leaders |

Servant Leaders |

Are content experts, based on position and power |

Are context experts, based on credibility, genuineness, and inspiration |

Are involved in directing tasks |

Facilitate plans and agreements based on group input |

Communicate and receive feedback |

Structure activities so that stakeholders and team members evaluate them, their leaders, and one another |

Have some meeting management skills |

Are skilled in using groups to build complex outputs by structuring conversations based on a collaborative tone |

Remain accountable for results |

Transfer ownership so that members are highly skilled and accountable for outcomes |

Value teamwork and collaboration |

Focus on removing impediments while providing procedures that fortify self-organizing teams |

Ironically, the more structured the meeting, the more flexible you (the meeting facilitator) can be. For without structure, a meeting design, or a road map, you can never tell exactly where you are or, more important, how much remains undone. With structure, you can take the scenic route, because you have a plan that references your original design—whereas groups without structure who take the scenic route get lost or, worse, cannot agree on where to go next.

With that said, I will not waste your time by covering the background and history of facilitation, giving you an overview of facilitation, or mentioning any other material not directly applicable to helping you become a better servant leader (or meeting facilitator). I’ll focus on critical thinking and how a structured method of facilitation generates the highest level of flexibility. As I noted earlier, structure does not hamper or restrict flexibility; structure makes it easier for you, as the servant leader, to be flexible and practical.

In addition, I will not spend much time on activities designed to improve teamwork, increase trust, and so on—in other words, what most other resources publish about “facilitation.” Rather, this book focuses on meeting objectives and outputs of business meetings, frequently referred to as “deliverables.”

Benefits of Embracing a Facilitative Leadership Technique

When organizations support skilled and facilitative leadership for product development, project management, process improvement, and so on, they are allocating human capital to ensure the success of their single most expensive investment: meetings. Organizations do so in these ways when:

- context is carefully managed, teams are free to focus on greater quality and value—quality being defined as satisfying customer expectations and value being defined as exceeding customer expectations.

- staff are treated like partners and collaborators, commitment and motivation increase.

- stakeholders’ ideas are sought, meetings become collaborative, innovative, and vibrant.

The value of embracing the servant leader–facilitative leadership technique extends beyond meetings to benefit a widening circle of people:

-

You benefit by

- – earning respect and recognition for leading better meetings

- – increasing your leadership consciousness, facilitation competence, and meeting design confidence

- – learning how to modify and adapt proven agendas, procedures, and tools for information gathering, analyzing, and decision-making

-

Your organization benefits by

- – expediting the output of highly sought deliverables

- – improving the culture and team spirit while enabling outstanding individual performances

- – reducing the cost of omissions and issues subject to normal oversight

- – reducing the cost of wasted meetings and wasted time in meetings

-

Your community benefits by

- – encouraging shared planning efforts to improve the distribution of resources

- – improving volunteerism

- – increasing decision transparency

- – solidifying shared ownership

-

All society benefits by

- – increasing eco-effectiveness through reducing wasted time and resources

- – improving the likelihood of win-win scenarios

- – motivating hitherto unused or underused intellectual capacity

Throughout this book, I aim to shift your thinking from “facilitation” (a noun, representing a static way of being) to “facilitating” (a verb, representing a dynamic way of doing)—that is, truly making it easier for your meeting participants to make more informed decisions. Leading is about stimulating and inspiring people, and facilitating skills are part of the DNA of servant leaders.

Facilitation Liberates Leaders

In the past, leaders needed to be experts on content. Today, organizations already employ and engage a wealth of subject matter experts. What organizations need are leaders who know how to be facilitative while managing context. In the past, leadership was about giving answers. Today, leadership is about asking precise and properly sequenced questions while always providing a safe environment for everyone’s response.

Imagine the following scenario: Your team is tasked with developing a plan to solve the problem of employee burnout in the cybersecurity department. To assess the value of proposed solutions, the team needs to know the purpose of the cybersecurity department—why it exists.

WHICH OF THE FOLLOWING MAKES BETTER SENSE?

A “presenter” might access the cybersecurity department charter from Human Resources. In most organizations, this task would take from 15 minutes to five hours or longer. Then the presenter might spend another 15 minutes putting together PowerPoint slides and then take five minutes to present the slides and another 10 to 20 minutes to manage questions and answers about content on the slides. Call it one hour total, minimum. At the conclusion, the presenter owns the content on the slides.

Alternatively, you, as the meeting leader, can use a procedure, such as my Purpose Tool (chapter 7).2 The Purpose Tool distills a consensual expression about the purpose of the cybersecurity department directly from the subject matter experts who understand both the purpose and the problems in the department today. In 15 minutes or less, you can lead the team to build an expression of shared purpose using the Purpose Tool. Most important, at the end of the 15 minutes, the meeting participants, not you, own the results.

A structured technique bestows ownership on your participants right from the beginning. But the real joy is that once you understand how to use a particular tool (for example, how to manage the context), you can use it repeatedly. Moreover, you don’t need to have detailed expertise on specific content. You need to have only a conversational understanding about the terms being used.

RAISE YOUR CONSCIOUSNESS ABOUT MEETING ROLES

From this point on, I’ll raise your consciousness around the roles of meeting designer, meeting facilitator, and meeting leader by helping you understand these concepts:

- As meeting leader, how to think separately about facilitation and meeting design

- How critical it is for facilitators to remain content-neutral—passionate about results, yet unbiased about path

- How to apply facilitator skills, such as precise questioning, keen observing, and active listening, to improve meetings

- The fact that the meeting coordinator, meeting documenter, meeting facilitator, and meeting designer are not persons but rather roles that are frequently performed by one person