Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Radical Product Thinking

The New Mindset for Innovating Smarter

R. Dutt (Author) | Radhika Dutt (Author) | Peter Noble (Narrated by)

Publication date: 09/28/2021

Iteration rules product development, but it isn't enough to produce dramatic results. This book champions Radical Product Thinking, a systematic methodology for building visionary, game-changing products.

In the last decade, we've learned to harness the power of iteration to innovate faster—we've invested in a fast car, but our ability to set a clear destination and navigate to it hasn't kept up.

When we iterate without a clear vision or strategy, our products become bloated, fragmented, and driven by irrelevant metrics. They catch “product diseases” that often kill innovation.

Radical Product Thinking (RPT) gives organizations a repeatable model for building world-changing products. The key? Being vision-driven instead of iteration-led. R. Dutt guides readers through the five elements of the methodology (vision, strategy, prioritization, execution and measurement, and culture) to develop a clear process for translating vision into reality, and turning RPT skills into muscle memory.

This book offers refreshing solutions to the shortcomings of our current model for product development; be prepared to toss out everything you know about a good vision and learn how to measure progress to create revolutionary products. The best part? You don't have to be a natural-born visionary to produce extraordinary results.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Iteration rules product development, but it isn't enough to produce dramatic results. This book champions Radical Product Thinking, a systematic methodology for building visionary, game-changing products.

In the last decade, we've learned to harness the power of iteration to innovate faster—we've invested in a fast car, but our ability to set a clear destination and navigate to it hasn't kept up.

When we iterate without a clear vision or strategy, our products become bloated, fragmented, and driven by irrelevant metrics. They catch “product diseases” that often kill innovation.

Radical Product Thinking (RPT) gives organizations a repeatable model for building world-changing products. The key? Being vision-driven instead of iteration-led. R. Dutt guides readers through the five elements of the methodology (vision, strategy, prioritization, execution and measurement, and culture) to develop a clear process for translating vision into reality, and turning RPT skills into muscle memory.

This book offers refreshing solutions to the shortcomings of our current model for product development; be prepared to toss out everything you know about a good vision and learn how to measure progress to create revolutionary products. The best part? You don't have to be a natural-born visionary to produce extraordinary results.

R. Dutt is an entrepreneur and product executive who has built products in industries such as broadcasting, media, advertising, technology, government, consumer, robotics, and wine. She is the cofounder of the Radical Product movement, which was designed to create vision-driven change. Dutt has participated in four acquisitions driven by the products she built, and she has spoken at conferences such as UX Fest, TiE StartupCon, ProductCamp, ProductTank, and e27 Academy. For the past year, she has served as the advisor to the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Dutt graduated from MIT with an bachelor s of science degree and master s degree in electrical engineering, and she frequently travels around the world to deliver workshops and talks.

CHAPTER 1

WHY WE NEED RADICAL PRODUCT THINKING

A vision-driven product begins with a clear picture of the change you want to bring to the world. This vision must then permeate every aspect of the product’s design.

For a great case study on how a vision-driven product is fundamentally different from an iteration-led one, consider the comparison between Tesla’s Model 3 and GM’s Chevy Bolt. Sandy Munro, a well-known automotive expert, shared a detailed comparison of the Model 3 and the Bolt after taking apart the two cars and painstakingly analyzing each component. Munro summarizes his findings in an Autoline After Hours interview, describing the Bolt as a “good car.” But he was far more excited by the Model 3. “Tesla has the best design for electronics, the best harness design, the best driving experience, the best motor.… Everything apart from the skin is brilliant.” His only criticism of the Model 3 was the body—an area where Tesla has admitted to having problems.

Munro gives an example of Tesla’s vision-driven innovation: a smaller, cheaper, and more powerful engine. He says he had heard about the Hall effect in electric motors, which can make the motor 40 percent faster, but had never seen it used in electric vehicle (EV) engines. In his teardown comparisons to date, Tesla was the only carmaker using the Hall effect for its engine. It required Tesla to invent a new manufacturing process to glue together magnets of opposing polarity under high stress. Munro had never seen anything like Tesla’s magnets before and couldn’t figure out how anyone could mass-produce them.

Compare that to his description of the approach GM took to build the Bolt: “GM doesn’t have a lot of money to spend on designing every vehicle from scratch. So they started with a Spark chassis, outsourced the battery, and got a car to market quickly.” GM was iteration-led and found a local maximum in the Bolt.

The difference between how Tesla and GM approached the race to build commercially viable electric cars is evident in the vision behind these two cars. Tesla’s Model 3 was driven by a radical vision of building an affordable car that didn’t require a compromise from the driver to go “green.” When GM designed the Chevy Bolt, it was driven by the vision of beating the Tesla Model 3 to market with an EV that would have a range of more than 200 miles between charges.

Tesla designed the Model 3 as a mechanism to create the change it wanted to bring to the world (accelerating the transition to electric cars by making them more affordable)—that’s Radical Product Thinking. This clear purpose was translated into every aspect of the car. One team designed a more efficient electric motor using the Hall effect; another designed a new magnet with varying polarities; another figured out a process to manufacture this innovative magnet. The connection across these roles and tactical activities is that the teams were all thinking about a radical product, driven by a common vision. As Munro summarized his view on the Model 3, “This car is totally different. This is not inching up. This is revolutionary.”

Thinking radically about a product is often reflected in the organization’s structure. Take the cooling system in the Model 3, a single system that cools the entire car, including the batteries, cabin, and motor. It was designed as a single system to be as efficient as possible. In the Bolt, as in traditional cars, separate systems cool the different areas of the car. As Munro points out, at GM, each of these systems is someone’s domain and fiefdom.1 While creating a single cooling system has been talked about a lot in Detroit, it would require “crossing over too many lines.” At Tesla, the radical vision transcended organizational boundaries.

GM was able to find local maxima—it got a new model to market quickly, and it was a pretty good car at a lower price point. But Tesla found the global maximum, a breakthrough vehicle that has been outselling the Mercedes C-Class, BMW 3 Series, and Audi A4 combined.2

Tesla used iterations to refine how to get where it was going. Tesla’s first iteration, the Roadster, ran on battery packs made of 6,831 off-the-shelf lithium-ion cells used in laptop batteries. Today Tesla’s Model 3 battery packs contain cells that were developed by the company with Panasonic. Munro views Tesla’s batteries as the best among the EVs—they provide the longest range and fastest charging times while occupying the least space. The company continues to iterate on its product. Tesla has acknowledged issues in manufacturing the Model 3 and continues to improve the design of the body and manufacturing processes.

GM, in contrast, used iterations to define where it was going. By starting with the same chassis as the Spark, even the same layout of the engine in the front, GM was preserving what it knew best (gasoline cars) and guaranteed that the Bolt would be evolutionary but not revolutionary.

“But wait,” you might say, “Tesla had a lead on EVs. Given more time (and iterations), wouldn’t GM have found the same global maximum that Tesla found?” Fortunately, we can use historical evidence to answer this question: coming up with a visionary solution wasn’t a matter of iterating for long enough. It turns out GM had launched its first electric vehicle, the EV1, in 1996, well before Tesla was conceived.

GM leased the EV1 as a market test to customers in California, who loved the product. In fact, when GM wanted to shut down the program, citing liability issues and discontinuation of parts, customers sent checks to GM asking to buy their leased cars at zero risk to the company. GM didn’t even have to commit to servicing the cars—their owners wanted to keep using them regardless! GM returned the checks and chose to shut down the product line because an electric car has fewer moving parts and requires fewer parts to be replaced in the car’s lifetime—the EV1 would have cannibalized GM’s spare parts business.3

While GM had come up with an EV well before Tesla, their iterations weren’t vision-driven and it settled for the local maximum. Ironically, GM’s cancellation of the EV1 program led Elon Musk to start Tesla and eventually build the visionary Model 3.

Despite their shortcomings, local maxima are often tempting because they can help you optimize for your corner of the chessboard. They can help you maximize profitability and business goals in the near term, as GM did by scuttling its EV program.

Since the 1980s the ideology of shareholder primacy, where a company’s primary goal is to maximize shareholder value, has become entrenched in business culture.4 Academics argued that managers would best serve companies (and society) by working to maximize shareholder value. Often this means delivering financial results every quarter to meet shareholders’ expectations of profits and growth—you’re incentivized to optimize for just a few pieces on the chessboard.

Startups too have similar incentives for a short-term focus. To demonstrate progress to investors and raise your next round of funding, you need to show quick results in terms of financial metrics or key performance indicators (KPIs), for example, the number of users, revenues, and growth. Irrespective of the size of the organization, the success of a product is typically measured on a single dimension: financial KPI.

The book Lean Startup taught us to innovate faster by testing things in the market, seeing what works, and iterating. But to assess what’s working, we almost always look to financial metrics, typically usage or revenues. Don’t know whether customers want the feature you have in mind? Launch it and let the usage data drive your decision. An iteration-led approach can move financial KPI up and to the right, but it doesn’t guarantee that you’ll build game-changing products. On the chessboard, optimizing for capturing a few pieces doesn’t guarantee that you’ll win the game.

Ironically, I’ve found that the pure pursuit of financial metrics often gets in the way of building successful products. When Lean Startup was published in 2011, it promised to democratize innovation. In a growing economy where credit was plentiful, the movement popularized the phrase “Fail fast, learn fast,” in the tech industry. It emphasized launching a minimum viable product (MVP) to test and refine an offering instead of spending time on an elaborate business plan. The Lean approach is typically paired with Agile, a development methodology for building products incrementally and incorporating feedback throughout the development process. Especially when Lean and Agile are used together, it creates the illusion that you don’t need to start with a clear vision—you could discover your vision along the way.

The problem with discovering your vision along the way is illustrated by the dialog between Alice and the Cheshire Cat in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where—” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.5

In discovering your vision along the way, your product can become a sailboat at sea without a North Star—you go wherever the currents and KPIs take you. As a business leader, you experience many strong forces pushing you in different directions. Your investors may see a trend that you’re not capitalizing on, a board member may share an idea (because he sat next to another CEO on a plane who “knew” just what your company should be doing), and different customers may be asking for different things. Without a clear vision and strategy to drive the ideas you test and iteratively improve, many good products go bad as they meander and lose their way.

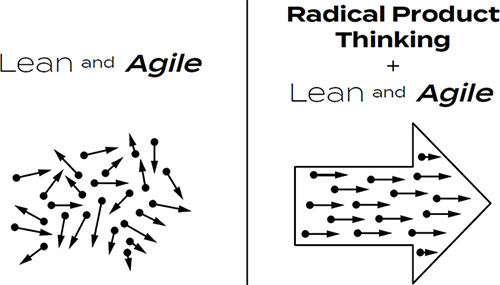

To be clear, this is not to dismiss Lean Startup. Lean and Agile are both excellent methodologies that I still use and highly recommend for feedback-driven execution. Lean and Agile give you speed, helping you get to your destination faster. However, they don’t tell you where you need to go.

Over the years, through my work in different industries and types of organizations from startups to government agencies, I’ve found the same pattern of mistakes as we build and scale our products and companies using iteration-led approaches to pursue local maxima. I was sharing my learnings and frustrations about product development with two ex-colleagues, Geordie Kaytes and Nidhi Aggarwal. Though they came from different backgrounds, they echoed my frustrations—both had also learned to build products through trial and error. Kaytes was a UX (user experience) strategist at Fresh Tilled Soil, a design agency in Boston, while Aggarwal had founded QwikLABS (acquired by Google) and was later the COO at Tamr, a machine learning startup. Among the three of us, we had built innumerable products over the years, and we saw the need for a methodical approach for building successful, vision-driven products. We realized that we must look at products differently.

We found that without a methodology to do this, organizations commonly use Lean and Agile execution to fill the gap. Using these methodologies while measuring success on the single dimension of financial metrics made it easier to find the local maxima but miss out on the global maximum. We cataloged the most common barriers that have repeatedly gotten in the way of building great products as a result of this approach. We spoke with people in diverse functions, industries, and countries who all faced similar problems.

We began to call these barriers diseases because they are contagious, damaging, and difficult to cure. These diseases are common because it’s easy to make mistakes at every step of product development.

We worked on translating what we had learned the hard way into a systematic process that anyone could apply. We drew insights from large and small businesses, nonprofits, and governments, and we organized them into a clear, repeatable process. We then tested and refined this process by working with individuals and teams in a range of organizations around the world, including early-stage high-tech startups, companies offering professional services, social enterprises, nonprofits, and research organizations. The result is what we call Radical Product Thinking.

The word radical can sound overwhelming, but the Oxford English Dictionary defines it as “relating to or affecting the fundamental nature of something (especially of change or action); far-reaching or thorough.”6 Radical in reference to medical treatment means thorough and intended to be completely curative.

Radical Product Thinking means being inspired by a change you want to bring to the world and thinking about your product comprehensively as a mechanism for creating that change. We’ve designed our Radical Product Tool Kit as a clear, repeatable methodology for creating game-changing products—step by step from envisioning a change to translating your vision into daily activities to delivering a final product. RPT will also give your team a shared language that makes communication easier and helps you bring others on your journey.

Here are the three pillars of the RPT philosophy:

1. Think of your product as your mechanism for creating change: The change you are working to bring to the world isn’t necessarily through a high-tech product. It could be through the work of your nonprofit, the research you’re conducting, or the freelance services you’re offering. Any of these could be your product if it’s your mechanism to bring change. Consequently, you can apply the RPT approach to any product you’re building to create change more effectively.

2. Envision the change you want to bring to the world before engineering your product: A product does not justify itself—it exists only to create your desired change and is successful only if it helps you achieve the end state you pictured. You can build the right product and evaluate it only if you know the impact you want to have. Without knowing the desired impact, it’s difficult to recognize and address the unintended consequences your product may have.

3. Create change by connecting your vision to your day-to-day activities: A focus on execution feels satisfying—it feels like being on a galloping horse (even if it’s galloping in the wrong direction). The RPT approach helps you connect your vision for change to your day-to-day activities so you can engineer that change systematically.

Table 1 presents a summary of the fundamental differences between an iteration-led approach and the RPT way.

SINGAPORE AS A RADICAL PRODUCT

Singapore’s history and economic transformation illustrate why Radical Product Thinking is a powerful model for creating change.

In 1854 the Singapore Free Press described Singapore as a small island filled with the “very dregs of the population of southeastern Asia.”7 Singapore had become a major port as a British colony, but the population was mostly poor and uneducated. Prostitution, gambling, and drug abuse were widespread, cholera and smallpox took their toll in overcrowded areas, and most people had no access to public health services. After World War II, Singapore chose to merge with Malaysia in 1963.

TABLE 1. Differences between an iteration-led approach and RPT

Iteration-led |

RPT |

|---|---|

This approach works for an evolutionary product when you’re making small changes to an existing product or process. |

RPT is needed for a game-changing product when you’re creating a transformative change. |

The vision is driven by business goals. |

The vision is driven by the change you want to see. |

The vision changes based on iterations, and iterations determine where you need to go next. |

The vision rarely changes—iterations help you refine how to get where you want to go. |

This approach helps you react to the situation you’re in to find local maxima. You optimize for a few pieces on the chessboard that are under attack. |

RPT helps you pursue the global maximum purposefully. You know the end goal and you play the long game in finding the best move across the chessboard. |

The resulting product can easily become bloated and unfocused over time, as common product diseases creep in. |

The resulting product is more likely to stay true to its original vision and purpose. Product diseases are less likely. |

This approach contributes to digital pollution as iterations may create unintended consequences in society. |

RPT helps you embrace the responsibility that comes with the power of building successful products that affect people. |

At the time, it didn’t seem like being an independent country was a realistic option. Singapore’s future looked uncertain—it faced mass unemployment and housing shortages and lacked natural resources such as petroleum. It was a small island that even depended on Malaysia for its drinking water. It wasn’t clear that such a country would survive.

Even the first prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, believed that Singapore’s place in the world was as part of Malaysia. But after violent race riots in 1964, the government acknowledged that the merger had failed. Singapore hesitantly became an independent country in 1965. In the first press conference after independence, an emotional Lee said, “For me, it is a moment of anguish because all my life … you see, the whole of my adult life … I have believed in the Merger and the unity of these two territories. You know, it’s a people, connected by geography, economics, and ties of kinship.”8

But Singapore’s history and the failed merger helped Lee formulate a clear picture of the impact he wanted to create for Singaporeans. In a different press conference, he described the world he wanted to create: “I have a few million people’s lives to account for. And Singapore will survive, will trade with the whole world and will remain non-communist.” Having experienced race riots while being part of Malaysia, Lee wanted to create equality among races. “There will be no race riots in Singapore. Never!”9

In an interview with the International Herald Tribune (excerpted in the New York Times) in 2007, he described that his mechanism to bring about the change he envisioned was to produce “a first world oasis in a third world region. So not only will [companies] come here to set up plants and manufacture, they will also come here and from here explore the region.” His vision was to create a platform for businesses to explore Asia.

In the same interview, Lee described his strategy for developing a “first world oasis.” Singapore needed to address the needs of Western businesses to make the island feel like home. The city needed to be green, be clean, and speak the same language (English). “We knew that if we were just like our neighbors, we would die. Because we’ve got nothing to offer against what they have to offer. So we had to produce something which is different and better than what they have. It’s incorrupt. It’s efficient. It’s meritocratic. It works.”10 It’s striking that he spoke as if he was building a product. Radical Product Thinking wasn’t a thing in the ’60s, but Lee had intuited this approach to systematically designing a product to create change.

The initiatives to arrive at these changes were carefully planned out and prioritized. For example, Singapore today is known for its cleanliness; in the West, we attribute this to the country’s strict rules and the threat of punishment for littering. But logistically, if the majority weren’t bought into the vision, enforcement would be very difficult. To achieve compliance from the population, the strategy has always been to persuade the majority through education campaigns and only then could fines and punishments be enforced for the willful minority.11 For a clean Singapore, the country had to first conduct an education campaign on why cleanliness was important to achieve the vision before fines could be instituted. Every element of the strategy, from cleanliness to making English the common language, had to be translated into a prioritized set of activities.

When we look at our product as a means to get us to our destination, we become open to the possibility of constantly improving our mechanism for getting there. This is where iteration fits in. Iteration allows for a feedback-driven approach to executing on a clear vision and strategy. In the 2007 interview, Lee shared how he used iteration: “We are pragmatists. We don’t stick to any ideology. Does it work? Let’s try it and if it does work, fine, let’s continue it. If it doesn’t work, toss it out, try another one. We are not enamored with any ideology.”12 The administration’s iterations were driven by a clear vision and strategy, but when an iteration proved that the underlying vision or strategy was flawed, the government corrected for it.

An example of iterative execution was Singapore’s approach to public transport. The vision for public transport was clear—to have an inexpensive and extensive public transport system that accommodated a growing population. In 1995 Singapore privatized public transport in an effort to increase efficiency and improve pricing through competition. While this strategy seemed reasonable, it turned out that SMRT, the corporate entity managing public transport, was prioritizing short-term earnings because it was a publicly listed company. Trains became plagued by delays and safety incidents as railway maintenance and long-term investment were neglected for years. When it was clear that the privatization strategy wasn’t achieving the vision for Singapore’s public transport, the government changed its approach. SMRT was bought out by Temasek (a government investment arm) and delisted. Today Singapore’s urban transportation is among the best globally and was ranked number one by McKinsey & Company in 2018.13

Lee led the Singaporean government when its challenge was to create a better life for the citizens of an impoverished island—he built a radical product and pursued the global maximum. Lee even used the analogy of playing a game of chess. “Some people play draughts—you eat one piece at a time. The affairs of men and nations are not that simple. This is a complicated business of chess.”14

Today’s administration faces a new challenge: the growing wealth inequality and balancing resource redistribution while living in the reality of a competitive, globalized economy. Beyond Singapore’s miraculous transformation, Lee’s visionary contribution was instilling a vision-driven product thinking approach in the government so the country could similarly engineer solutions to different challenges it would face in the future.

You can still see this approach permeating across the government agencies in Singapore. Every ministry or government organization has its own vision for the impact that it is working to create, and each has its corresponding product. Walk into any government organization and you’ll see its vision clearly posted on a wall, and the service you experience matches it. At the end of your interaction, you are typically surveyed for feedback on your experience to constantly improve the product.

Here’s my first experience of product thinking in a Singaporean government office. I arrived in Singapore with my family, and the very next day we went to the Ministry of Manpower’s Employment Pass Services Center (EPSC) to get work permit cards. I was bracing myself for a long and painful experience as we headed there with two jet-lagged kids who had been up since two o’clock that morning.

Instead, we had an overwhelmingly positive experience that started with us walking into an office that looked more calming than most therapists’ lobbies. During the short wait, we perused signs around the office that described the EPSC’s design goals in crafting the customer experience: “Giving you certainty and control,” “Keeping your different needs in mind,” and “Being personable.” The experience was true to these design goals, for example, our jet-lagged kids were happy in the cozy kids’ zone, and when it was our turn we were called by name rather than a number. The staff took our pictures for the pass (we didn’t have to find a photo booth), and they even gave each of us the opportunity to review our photo and decide if we wanted to have it retaken! And just like that, our work at the EPSC was done and the work permits would be mailed to us.

Issuing work permits is EPSC’s “product,” and this product is aligned with the vision articulated on the Ministry of Manpower’s website. Here’s an excerpt:

We aim to develop a great workforce and a great workplace. Singaporeans can aspire to real income growth, fulfilling careers and financial security, while we maintain a manpower-lean and competitive economy.

To achieve our vision and mission, we aim to enable companies to provide good jobs and Singaporeans to take up good jobs, to build a strong Singaporean core.

We will maintain a skilled foreign workforce to complement our local workforce.15

To achieve this vision, Singapore needs to attract a skilled, diverse, foreign workforce. These workers fill a crucial gap in the labor force given the aging local population, hence the design goals that make working in Singapore easy for this group.

Lee’s product was a “first world oasis”; EPSC’s product was issuing work permits. Every level in an organization can apply Radical Product Thinking and create an impact through its product. At a more granular level, each person in an organization contributes a unique product. The impact created by the organization is the collective impact of each of these products.

The power of this model of product thinking is that we can apply it up and down the organizational hierarchy. Each team is driven by a clear vision for the change they are working to create. In organizations that are iteration-led instead of vision-driven, I’ve found that different teams in the organization are often iterating quickly but not always in sync.

Lean and Agile have taught us to harness the power of iteration through tight feedback loops—these execution methodologies give you speed. Radical Product Thinking gives you direction, helping you plan where you want to go and how you’re going to get there. Combining iterative execution with Radical Product Thinking gives you velocity: speed with direction. The design firm PebbleRoad uses the illustration in figure 1 to represent the challenge it sees in organizations and the value of Radical Product Thinking.

This new mindset helps you take a more disciplined and visionary approach. The example of Singapore shows the importance of a clear vision that drives a strategy, priorities, and execution. Singapore didn’t have many chances to iterate—it had seen other countries fall into decades of civil war by making mistakes in translating vision into execution. For many companies that build mission-critical products, iteration is not an option.

Iteration is helpful, but our iterations must be driven by a vision. We measure progress toward the vision to decide how to improve our next iteration. By taking this vision-driven approach, we engineer successful products to bring about the change we want to see in the world. Visionaries such as Lee Kuan Yew and Steve Jobs knew intuitively how to turn their concepts into reality. The rest of us could use a guide.

FIGURE 1: Lean and Agile give you speed, RPT gives you direction, the combination gives you velocity

This book offers a clear, repeatable methodology for creating a vision-driven impact—from envisioning a change in the world to delivering it. It’s a step-by-step approach to help you translate your vision so it permeates the daily activities that engage you and your team. Equally importantly, it’s a shared language that makes communication easier and helps you bring others on the journey with you.

To introduce this new way of thinking, you need to start by understanding what gets in the way of building good products and the pattern of diseases that kill innovation. This vocabulary will help you spread this thinking within your organization—you’ll be able to help others recognize these diseases so you can start to overcome or prevent them.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• An iteration-led approach can move financial KPI up and to the right, but it doesn’t guarantee that you’ll build game-changing products.

• In an iteration-led model, iteration defines where you go. In a vision-driven approach, iteration helps you refine how you get to your destination.

• Radical Product Thinking helps you build vision-driven products that help you create the change you envision.

• Here are the three pillars of the RPT philosophy:

1. Think of your product as your mechanism for creating change.

2. Envision the change you want to bring to the world before engineering your product.

3. Create change by connecting your vision to your day-today activities.

• Radical Product Thinking gives you direction, Lean and Agile give you speed. Together you get speed plus direction (i.e., velocity).

• In the RPT way, anything can be your product if it is your constantly improving mechanism to create the change you want to bring about.