Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Simply Put

Why Clear Messages Winand How to Design Them

Ben Guttmann (Author)

Publication date: 10/10/2023

Simply Put is a modern exploration of the simplicity principle for anybody who needs to sell stuff or persuade others. This book is a splash of cold water, designed to wake up entrepreneurs, C-suite executives, and marketing pros who have something they need to tell the world but just can't quite connect the dots. With this book, we're all better marketers.

So why does simple win? And how do we get simple? The award-winning marketing entrepreneur behind New York Times best-selling authors and notable campaigns such as I Love NY provides answers and tools to simplify messages in this practical guide.

From Yes We Can to Just Do It, regardless of if they're trying to get your dollars, your votes, or just your thoughts, effective messages share one thing they're simple. Being able to tell your story clearly and effectively is the winning skill for the next generation of entrepreneurs and leaders.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Simply Put is a modern exploration of the simplicity principle for anybody who needs to sell stuff or persuade others. This book is a splash of cold water, designed to wake up entrepreneurs, C-suite executives, and marketing pros who have something they need to tell the world but just can't quite connect the dots. With this book, we're all better marketers.

So why does simple win? And how do we get simple? The award-winning marketing entrepreneur behind New York Times best-selling authors and notable campaigns such as I Love NY provides answers and tools to simplify messages in this practical guide.

From Yes We Can to Just Do It, regardless of if they're trying to get your dollars, your votes, or just your thoughts, effective messages share one thing they're simple. Being able to tell your story clearly and effectively is the winning skill for the next generation of entrepreneurs and leaders.

Ben Guttmann is a marketing entrepreneur and educator who has helped hundreds of clients, ranging from the NFL to Nobel Laureates, from I Love NY to #1 New York Times best-selling authors. He is co-founder of Digital Natives Group, which has worked with more than 60 authors. Since 2014, he has taught at Baruch College and has been a fulltime community leader in New York City, active in Long Island City Partnership, Queens Economic Development Corporation, Queens Community Board and Queens Tech Night.

-William Ury, New York Times bestselling coauthor of Getting to Yes and Getting to Yes with Yourself

Ben has an uncanny ability to distill the complex into clear-eyed, empathic communication. With Simply Put, he helps us to connect with ideas in ways that are at once practical and energizing. If you need to communicate your work more effectively, this is your book.

-Michael Ventura, author of Applied Empathy and founder and former CEO, Sub Rosa

My review of Ben Guttmann's excellent book Simply Put . . . is simple. An excellent read. Buy it. Learn from it. Adopt it. It's that simple.

-Martin Lindstrom, New York Times bestselling author of Buyology and Small Data

Simply Put gifts us new approaches and techniques to amplify our voices and share our ideas. How we craft our message is fundamental to our success, and these lessons make us more impactful and influential communicators.

-David Perlmutter, MD, New York Times bestselling author of Grain Brain, Brain Wash, and other titles

Simply Put is a brilliant and necessary road map for all business leaders to learn how to become more effective communicators. This is a useful book that invites you to see things differently and craft clear messages.

-Jessalin Lam, coauthor of The Visibility Mindset and cofounder of Asians in Advertising

It is so refreshing to read Ben's words about keeping things simple. It's interesting that all the entrepreneurs I have talked to seem to have one thing in common: they started out with a very simple idea-one that was easy to understand and even easier to scale. To be successful, these are words to live by!

-Ken Rusk, entrepreneur and Wall Street Journal bestselling author of Blue Collar Cash

Ben Guttmann shares lessons typically learned through years of failure. Read this book and skip the failure. Clear and simple wins. Here's how to get there.

-David S. Pottruck, former CEO, Charles Schwab, and New York Times bestselling author of Stacking the Deck

One of my core beliefs has always been that boiling complex messages into simple maxims is one of the best ways to benevolently brainwash anyone. The question is, How do you do it? Ben Guttmann's new book finally gives us the answer in a big way. We finally have the definitive text on how to execute radical simplicity in the real world and get anything you want as a result.

-Michael Schein, author of The Hype Handbook

Every entrepreneur and brand leader should read this book. So many marketers struggle with how to communicate clearly, and Simply Put is an essential how-to guide to crafting messages that stick.

-Alexandra Watkins, author of Hello, My Name Is Awesome and founder of Eat My Words

My team and I were bedazzled by the clear, impactful messaging that Ben helped us craft. And now with Simply Put, Ben's skills are available to all of us in an easy-to-use, straightforward road map.

-Dr. Kara Fitzgerald, author of Younger You

You've heard the quote before: Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.' Ben has succeeded at creating clear guidelines that bring this age-old adage into action for the modern marketer.

-Maria Vorovich, founder and Chief Strategy Officer, GoodQues

We live in an age of mass, perpetual distraction. Simply Put is the straightforward guide to getting noticed, getting heard, and getting traction.

-Dr. Parag Khanna, international bestselling author of Connectography and Move

Being clear with our ideas is central to being effective. Ben is a wonderful partner in this process, and his new book, Simply Put, captures the essences of his effective framework.

-Drew Ramsey, MD, author of Eat to Beat Depression and Anxiety

Simply Put is a revelation! Bursting with clear, actionable insights, it's required reading for anyone with something to say, solve, or sell.

-Jonathan Fields, host of the Good Life Project podcast and bestselling author of Sparked

Drawing from a wealth of experience, Ben Guttmann provides tested techniques to leverage the most critical quality of effective communication: Simplicity. Using this insightful book as a North Star, readers will learn how to communicate decisively and effectively. I highly recommend Simply Put for anyone who wants to get to the point!

-Joel Schwartzberg, author of Get to the Point and The Language of Leadership

1

Our Stupid Brains in Our Busy World

To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work.

—Mary Oliver

How do you tie your shoes?

You’ve probably tied your shoes tens of thousands of times since you first learned to do so in grade school. The act is muscle memory by now. But could you explain it to somebody else?

How does a flush toilet work?

You’ve maybe flushed a toilet a hundred thousand times in your life. This machine is pretty simple, just a piece of curvy porcelain, a handle, and a few moving bits inside. No wires or chips are involved. But can you explain what happens when you push down that lever?

What did you eat for lunch two Tuesdays ago?

You were there, and it wasn’t that long ago. You walked into the restaurant and placed the order after scanning the menu, or you packed it up on the kitchen counter earlier that morning. You took a bite, hopefully enjoyed it, and cleaned up the scraps after. But do you remember exactly what it was?

These questions aren’t difficult, or at least they shouldn’t be. But we all struggle with them. We can’t remember most of what’s scurried across our attention, we don’t know as much as we thought we did, and we struggle with communicating even the things that we are the most experienced in. Our minds aren’t computers recording and processing everything in perfect precision—they are imperfect, fleshy machines.

Despite these limitations, we get along pretty okay most of the time. We tie our shoes, flush toilets, and eat lunch without any issues most days of the week. We’re good, talented users of the world around us. We run into trouble, though, when we’re thrust into the other role: when we become somebody who has something to say, build, or share. That’s when everything breaks down.

Most of our communications rely on a foundational idea: we are smart, caring, rational actors who pay attention and understand what other people are saying—in all ways all the time. But because of our nature and the world we’ve built around us, that simply isn’t the case.

This is the problem, this is why so many of our messages don’t get through. To put it bluntly, we’re stupid, and we’re busy.

The Problem with Us

The beautiful truth is that we are imperfect beings. Stories aren’t interesting without conflict, sweet doesn’t taste as good without salty, and life would be both boring and stressful if our brains worked perfectly every single time.

We know this because a handful of people in the world do notice and remember pretty much everything. A rare condition known as hyperthymesia allows these individuals to look back on their lives as a vivid movie, picturing the people, places, and things that make up their autobiography in the same way you or I might scroll through a photo gallery. While this memory is not perfect, it’s pretty damn close. Having this condition means recalling birthdays, weddings, breakups, and funerals all with the same level of detail. One patient describes it as “nonstop, uncontrollable and totally exhausting.”1 It’s not ideal.

We ignore and forget because it helps us live our lives. But when we’re somebody with a message that we don’t want to be ignored or forgotten, this biological programming can feel like an insurmountable obstacle. To understand the territory, let’s tour some of our biggest trouble spots.

We Don’t Notice Most Things

In an aggressively beige, nondescript hallway, six students move about in a circular pattern. Half of them are dressed in white shirts, and the others wear black shirts. Each color-coordinated team passes a basketball back and forth among themselves, smiling as they perform the demonstration in front of a closed bank of elevator doors.

A few seconds after they begin, an actor in a gorilla suit walks through the group, stares at the camera and pounds its chest, then heads off in the other direction. The students keep passing the ball.

Weird, right? That must have caught your attention.

Not necessarily. When the researchers who designed this test showed the scene to participants, tasking them before it played to count how many passes the team in white makes, only 42 percent of viewers noticed the gorilla. Incredibly, most viewers counted the fifteen passes the team made and saw nothing out of the ordinary.

This famous study by psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris illustrates the puzzling phenomenon of inattentional blindness, where we fail to notice something in plain sight.2 When we’re in a busy environment, distracted by a task or other stimuli competing for our attention, we’ll miss something right in front of us—even if it is an eight hundred-pound gorilla.

There is nothing special about that gorilla suit or basketball. This “blindness” happens all of the time.

When we’re engrossed in a conversation while behind the wheel, we’ll fail to see the car that “came out of nowhere.” When we’re so hung up on a particularly tough level of a video game, we miss our spouse entering the room asking about dinner plans. When we’re crunching on a work deadline in the airport lounge, we’ll go deaf to the blaring last-call announcement for our departing flight.

Nothing is wrong with our eyes or ears. Our retinas faithfully pick up these sights and feed the sensations through our optic nerve to the cerebral cortex. Our eardrums vibrate and pulse electrical signals up our auditory nerve. But often, something right there can fail to register in our consciousness. Instead, our brain takes shortcuts, filling in the blanks with what we expect to be there and getting on with whatever else we were doing.

Subconsciously filtering out unnecessary details has been evolutionarily advantageous in our development. Imagine how exhausting it would be to consciously process and consider every single thing that comes before us. Our ancient ancestors would have sat around, pondering and reviewing each blade of grass, quickly becoming a leisurely lunch for a hungry predator lurking behind a tree. But as any marketer who’s burned through an ad budget with vanishingly small click rates to show for it will tell you, this propensity to filter is bad if you’re trying to get somebody’s attention.

The psychologist Simons, who ran that gorilla study, later said, “One conclusion of the inattentional blindness work has been that we see far less of our world than we think we do…. We feel like we’ve got all the details of the things going on around us. But my bet is that most of the time people are really focused on one goal at a time.”3

By some estimates, we take in 11 million bits of information every second through our senses, but our conscious brain has the bandwidth to attend to about only 0.0004 percent of them.4 Long before we measured information in bits, pioneering nineteenth-century psychologist William James wrote, “Millions of items of the outward order are present to my senses which never properly enter into my experience. Why? Because they have no interest for me. My experience is what I agree to attend to. Only those items which I notice shape my mind—without selective interest, experience is an utter chaos.”5

Our attention is precious and finite, and we prefer to spend it on what matters to us. We notice information that is tied to our goals and helps us survive and thrive, but to do that, we subconsciously filter out the inputs that don’t matter as much. And often, that means failing to notice most of the messages bombarding us at any given moment.

We Don’t Remember Most of Everything

Late on a Friday night in December 2010, a frantic young man named Aaron Scheerhoorn showed up at the door of a Houston nightclub.6 He opened his shirt, revealing a bloody stab wound to the bouncers, and begged urgently to enter the club for safety. Despite these pleas, the doormen never let him in, soon allowing the large man following him to catch up and stab him again. After running away through a nearby parking lot, Scheerhoorn was stabbed several more times by the attacker, whom passersby saw eventually get up and calmly walk away. Later that night, Aaron Scheerhoorn was declared dead at the nearby hospital.

Over the course of the gruesome evening, eight witnesses saw the attacker. The next day, one of them reported that he spotted a man who he thought looked like the killer. The police tracked down this suspect’s name from his car: Lydell Grant.

Detectives shared photos of Grant with other witnesses. Two of the bouncers said that was him. Two of the patrons said that was him. The passersby from the parking lot said that was him. In total, six of the eight witnesses immediately identified Grant as the attacker they saw that night. The police had their man.

Several days later, Grant was pulled over, arrested, and charged with first-degree murder. The police found some other fuzzy evidence: a ski mask and knife in his trunk and some indeterminate male DNA scraped from under his fingernails. But the six witnesses were all the prosecutors needed to make their case. Two years later, on December 6, 2012, Grant was found guilty—and sentenced to life in prison.

Lydell Grant did not kill Aaron Scheerhoorn.

On the strength of DNA evidence, and with the help of the Innocence Project of Texas, Grant was released in 2019, and his conviction was soon formally overturned. The real killer, Jermarico Carter, confessed shortly after being arrested. The false conviction that stole almost a decade of Grant’s life was nearly entirely based on the faulty memory of six witnesses.

Sadly, this case is not a rare exception. Ronald Cotton was falsely convicted of rape and sentenced to life in prison in 1985 on flawed eyewitness testimony, only to be exonerated by DNA evidence in 1995. Ryan Matthews spent five years on death row for a crime he didn’t commit after nearby witnesses falsely identified him in 1999. According to the Innocence Project, 69 percent of DNA exonerations in the United States involve misidentification from eyewitnesses, and 32 percent of those involved multiple misidentifications by different witnesses.7

Even when the stakes are life and death, we have a hard time remembering what we saw, what we heard, or what happened.

In our brains, we have four forms of memory: sensory, short-term, working, and long-term memory.8 Sensory memory is the first, exceedingly brief store of information that comes in from our senses. It’s basically the gatekeeper that filters everything around us and selects what makes it through to our consciousness. All the stimuli from the world around us goes in and out of this station of memory in less than a second. This type of memory is what we talked about in the previous section.

If information makes it through this attentional filter, it arrives in our short-term memory. Our short-term memory is where we keep details at the top of our minds as we’re thinking and doing things in the world around us, such as the last sentence you read or a phone number you’re dialing.

Overlapping with short-term memory is our working memory, where we access, hold, and manipulate information to plan and carry out behavior. Working memory is how we put short-term memory to use, such as following recipe instructions, solving a math problem, or engaging in debate.

These three stages are also small and brief in storage.

In an influential 1956 study, Harvard psychologist George Miller discovered a consistent limit on short-term memory.9 It didn’t matter if people were trying to recall numbers, sounds, letters, or words. Everywhere he looked, he found our short-term memory limit was, as he titled the paper, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two.” According to Miller, we can reliably hold only about seven “chunks” of information in our head at any one time.

Subsequent research has pushed this estimate down to four. And still other studies have shown that this capacity might be better represented by time: we can typically recall only as much as what we can verbalize in roughly two seconds.10 Either way we cut it, this capacity is vanishingly tiny. In the short run, our attention and our capacity to retain information are much more limited than we would like to think.

Then we face another problem: our memory decays— fast. Unless we go out of our way to re-up its shelf life, new information is gone within about fifteen to thirty seconds. This is why you can’t easily remember the exact line that character said a few scenes back when watching a movie or what else was on the menu at the restaurant by the time your food arrives. Our brains processed the information, made use of it, and then tossed it aside after it served its purpose. Some stuff makes its way to our long-term memory storage, but the vast majority doesn’t. Forgetting, by clearing out the unnecessary mental clutter, isn’t the exception; it’s the default.

Largely because so much doesn’t clear these dual hurdles of attention and storage, we must question the reliability of what does. Leading researcher Elizabeth F. Loftus says that remembering is “more akin to putting puzzle pieces together than retrieving a video recording.”11 Each time we call up a memory, we’re not pressing play, we’re reconstructing it—and we’re susceptible to making mistakes while we do.

The eyewitnesses in the story of Lydell Grant and the other wrongly convicted exonerees above were wrong, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they were ill intentioned. Like most of us, their memory was far from photographic, and when they were called on to use it in a moment of incredibly high stakes, it failed them and everybody involved. As they tried to reconstruct a hazy memory, their mind put a few pieces together, filled in the rest with context clues, and said, “Okay, good enough.”

These witnesses were operating in high-stress, real-life conditions, often in the dark and from a distance, not memorizing a photograph in a dedicated study session. Only so much information was received, and even less made it to storage. When put head to head with a pushy prosecutor looking to score a conviction, their imperfect, limited, human memory didn’t stand a chance.

We Don’t Know What We Think We Know

Even when we notice something, even when we remember something, do we actually know anything? The truth is that we all know lots of things, and we get through most of our days just fine—but we also think we know a lot more than we really do.

Let’s go back to flush toilets, which we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. Details of your personal hygiene aside, you’ve likely been flushing away all your life, making this device one of your longest-running and most intimate technological interactions. But if you were sent back in time five hundred years, could you build one?

Unless you’re a plumber, if you answered yes, you’ve likely just fallen for another one of our mental shortcomings: the illusion of explanatory depth. This phenomenon is where people feel they understand complex topics, ideas, and systems more than they actually do.

In the original Yale study identifying this concept, graduate students were asked to estimate how much they understood how a series of devices or systems work, from speedometers and the US Supreme Court to, yes, flush toilets.12 After they rated their knowledge, the participants were told to write a detailed explanation of each idea and afterward rerate their level of understanding.

The results: nearly every single participant struggled with their explanations and lowered their rating of their own knowledge after doing so. When replicated with undergraduates or beyond the tony campuses of the Ivy League, the same results occurred. We don’t know what we think we know.

This illusion is related to another common quirk of overestimation: the Dunning-Kruger effect. This well-known cognitive bias is when inexperienced or incompetent people tend to overrate their ability or performance. We see this all around us: bad students think they’re getting better grades than they are, and poor chess players think they are more likely to win than they are. In a particularly jarring example, 12 percent of average, everyday British men believe they can score a point against Serena Williams, the greatest player of all time, in a game of tennis. Coincidentally, that’s the same percentage of overconfident Americans who somehow think they could defeat a wolf in a hand-to-hand fight.13

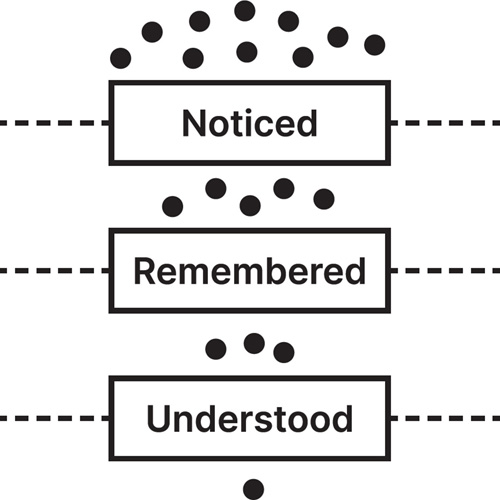

Taken together, these shortcomings play out every time we try to communicate, as shown in figure 1.1. At every step of the process of taking information from out in the world and getting it into our thick heads, we face problems. Each sliver of attention and focus is a tiny miracle.

Figure 1.1. Some stuff gets noticed, fewer things get remembered, and only a small fraction of things get understood.

The Problem with Everything Else

All these bugs may make it seem like we’re pretty faulty machines. But we’re not broken any more than a fish is broken for being unable to climb a tree or a snail because it can’t fly— they just aren’t built for these situations. We’re imperfect, but it’s not a moral failing. It just is.

The problem is that we’ve built a world that isn’t built for us.

Wandering the savanna 250,000 years ago, our earliest ancestors were not beholden to an endless horizon full of billboards or an infinite scroll of notifications. Instead, we evolved in a world with very real threats—dealing with many more things that wanted to eat us than we do today—and we developed behaviors that allowed us to quickly scan the environment and shift our attention to help us stay one step ahead. Some branches rustling or shadows shifting could indicate a predator around the bend, and immediately our eyes widen and our ears perk up to judge the threat.

As evidenced by the fact that you and I are still here, our ancient relatives were really good at not being eaten. These brains of ours worked! Our attention and memory filters did their job.

But today, we’ve invited that saber-toothed threat into our homes and pockets. Our devices cry out constantly, jolting our minds from one urgent thing to the next. And the pace is only quickening.

The Golden Age of Distraction

Every semester as I teach my undergraduates, I ask them to pull out their phones, tap over to the settings, and view their daily screen time totals. I then tell the class to shout out the biggest numbers. Here are some of their responses: “5 hours, 23 minutes,” “6 hours, 14 minutes,” “7 hours, 51 minutes.”

Taken in the context of a twenty-four-hour day, these numbers are wild—but they aren’t out of the ordinary. In the United States, 57 percent of adults spend five or more hours on their phones each day.14 I’m right there in the mix myself, racking up an average of four hours and seven minutes during the week I wrote this.

If we extend our view to all media, from smartphones to computers, television, radio, books, newspapers, and magazines, Americans average over thirteen hours a day of having messaging blasted into our brains.15 If you take away the time for sleeping and bathing, that’s pretty much everything.

In this time, we see and receive thousands of images and messages, from friends and family, from organizations and groups, and, of course, from advertisers, all stewed together in our algorithmic feeds. With our phones and apps designed to be addictive, some marketers estimate that we scroll more than three hundred feet daily through our various feeds, a distance longer than the Statue of Liberty is tall. We cover so much ground on our phones alone that doctors have reported a new malady dubbed smartphone finger, a form of tendinitis from the constant flick, flick, flick.

The battle against information overload is not new, but it has reached new heights. In 1255, Dominican Vincent of Beauvais complained of “the multitude of books, the shortness of time and the slipperiness of memory.”16 And that was nearly two hundred years before the printing press led to an explosion of the written word. As the centuries marched on, newspapers, radio, and television took up more of that “shortness of time,” and in the accelerating present era, it’s been ever worsening.

We’re struggling to stay afloat against this flood of information, installing ad blockers by the millions and unsubscribing en masse. We buy smartwatches to help clear notifications faster. These efforts don’t matter, though, as the large and powerful forces pushing the other way are incentivized for more and more and more. We live in the golden age of distraction, and piercing through this noise is harder than ever.

In his book Emotional Design, designer Don Norman explains the crux of the problem with these distractive technologies. By using them, “you are doing a very special sort of activity, for you are a part of two different spaces, one where you are located physically, the other a mental space, the private location within your mind where you interact with the person on the other end of the conversation.”17

This split consciousness, combined with this fire hose of information, creates a world unrecognizable to our great-grandparents, let alone our evolutionary forebears. We’re busy, with less downtime than hunter-gatherers by some estimates, and we’re distracted, receiving an average of one hundred twenty emails and fifty push notifications a day, and we’re simply unable to keep up.18

The Default Is Indifference

It’s not just you. The data shows that social media trends move faster today than even just a few years ago and that our interest in both the latest books and movies is more fleeting than it once was.19 More and more comes at us each year. Behind each wave of stuff screaming for attention, there is another bigger one. In this age of abundance, the deluge never stops.

The vast majority of us, nearly three-quarters of the population, say there are too many ads. And the ones that hijack our attention the most, blaring autoplay video ads, are considered far and away the most annoying.20 Whether by installing blockers or changing our habits to otherwise get around them, most of us do whatever we can to avoid advertising everywhere we can. Four US states even ban billboards.

The way we respond to this onslaught of annoyance is by tuning out. Our default is to ignore.

Banner blindness, a form of selective attention that blocks out these uninvited messages, has been documented in computer users for decades.21 Our brains are so trained to ignore ads, and even things that look like ads, when we’re using websites and apps that we instinctively know how to skip right by them even if we’ve never been to that page before. We literally don’t see these messages, and we certainly don’t receive them. The signal is lost in the noise.

This collective failure of communication results from our core, underlying, and all-too-obvious motivation: we just want to do what we want to do.

To put it bluntly, we don’t care about things unless they matter to us. We love and care deeply about our friends and families, our sports teams and political parties, our hobbies and our faith. These and many other subjects do matter to us and command our attention. But when we don’t immediately see that something aligns with our goals and desires, we move on to the next thing. And there are more of those next things than ever before.

Our brains created this mess, and they can get us out of it. As we’ve seen, before we even try to communicate, the deck is stacked against us. Our biology and psychology want us to tune the noise out, and the world we’ve created is so full of clutter and chaos that it’s a miracle anything gets through at all.

We’re bringing a Stone Age brain to a smartphone fight. It’s not our fault when we lose.

But we can’t just give in. We have important things to say, movements to build, and innovations to bring forth. Communication is too vital—to business, to our lives, to the grand project of society—to allow it to fail. It’s the essence of our humanity, and to do it right we must acknowledge and embrace our human limitations. To do the work to cut through and be heard is our responsibility.

And as it turns out, there’s a science behind how we can do just that.

What’s Going On in Our Heads

A lot of details are at play every time we create or communicate. Here’s a partial list of the ideas we discuss in our journey to understand how a message gets from sender to receiver:

• Availability bias—We are more likely to use ideas that are closer at hand.

• Complexity bias—We tend to look at situations, tasks, or issues as more complex than they actually are.

• False-consensus effect—We tend to overrate how much our opinions and choices are shared by everybody else.

• Fluency heuristic—We judge situations or ideas more favorably when they are easily perceived and understood.

• Homophily—We tend to associate with people who are similar to us.

• Instrumentality heuristic—We can sometimes prefer tasks that take more effort, but only when we’re motivated in pursuit of a goal.

• Overconfidence effect—We have a tendency to overestimate our performance, knowledge, and ability, particularly in areas of limited experience.

• Selective attention—We have the ability to tunnel our attention into a specific task, ignoring other details around us.