Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Targeting Turnover

Make Managers Accountable, Win the Workforce Crisis

Richard Finnegan (Author)

Publication date: 09/09/2025

In Targeting Turnover, Dick Finnegan draws on decades of experience and groundbreaking data to reveal a stark truth: the US is running out of workers. As baby boomers retire and birthrates fall, the only sustainable path forward is to keep the good employees you already have.

This book offers a proven, research-backed strategy for doing just that—by building trust between employees and their immediate supervisors.

Forget one-size-fits-all solutions like pay and perks. The top predictor of retention and engagement is whether employees trust their boss. Yet most first-line leaders have never been trained—or held accountable—for building that trust.

Finnegan delivers a call to action: make employee retention an executive-driven priority and equip your leaders to lead differently.

You will learn how to do the following:

- Use stay interviews and practical tools to reduce turnover

- Hold managers accountable for engagement and retention

- Understand the real costs of attrition—and how to reverse them

- Apply forecasting and metrics to drive leadership behavior

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

In Targeting Turnover, Dick Finnegan draws on decades of experience and groundbreaking data to reveal a stark truth: the US is running out of workers. As baby boomers retire and birthrates fall, the only sustainable path forward is to keep the good employees you already have.

This book offers a proven, research-backed strategy for doing just that—by building trust between employees and their immediate supervisors.

Forget one-size-fits-all solutions like pay and perks. The top predictor of retention and engagement is whether employees trust their boss. Yet most first-line leaders have never been trained—or held accountable—for building that trust.

Finnegan delivers a call to action: make employee retention an executive-driven priority and equip your leaders to lead differently.

You will learn how to do the following:

- Use stay interviews and practical tools to reduce turnover

- Hold managers accountable for engagement and retention

- Understand the real costs of attrition—and how to reverse them

- Apply forecasting and metrics to drive leadership behavior

Richard "Dick" Finnegan is CEO of C-Suite Analytics and the Finnegan Institute. A specialist in cutting turnover, he works with a variety of clients, from Quest Diagnostics to Sysco to Covenant Health, that have reported reductions in turnover of a minimum of 20 percent-often much more-using his research-based model to improve employee engagement and supervisor connection. A lifelong member of SHRM, he is the highest rated SHRM speaker based on audience surveys and wrote the highest-selling SHRM title, The Stay Interview. He holds a master's degree in education from Penn State and resides near Orlando, Florida.

1 ■ The Next Twenty Years Beware the Pig in the Python

Any smart discussion about employee retention must begin by detailing the exceptionally steep hill we must climb to find and retain good workers in the immediate future and beyond. The next two decades will bring profound changes to the US workforce because our baby boomers are leaving us, resulting in insufficient increases of our worker numbers along with skepticism that new worker quality will be as good. China, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Canada, and other leading economies face the same stiff challenges, resulting in all high-income nations racing to import the best immigrants in order to sustain their economies.

But let’s first look back on the people management challenges of the past twenty years, so we can compare the level of those obstacles to the ones contained in our twenty-years-out forecast.

Naming the COVID-19 pandemic as the major challenge of the past two decades is an easy call. A distant second would be the Great Recession. One way to compare the impact of each is to study the levels of workforce turbulence reported by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

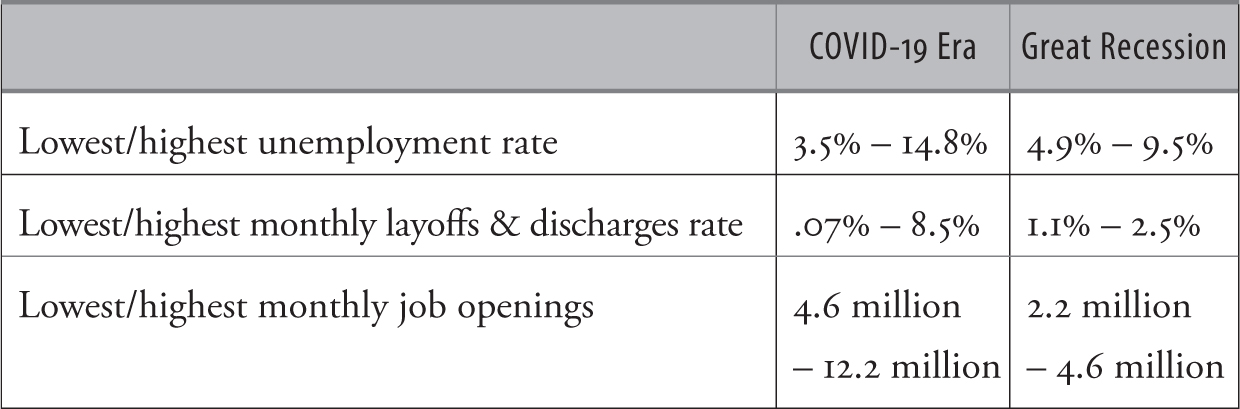

Figure 1 compares key workforce data from the Great Recession’s actual recession period of December 2007 to June 2009 to the same data points during the most crucial COVID-19 period of 2020 to 2022.1

The three data points of the “COVID-19 Era” column show the whiplash impact of initial workforce desperation, which was later followed by unprecedented workforce security (“COVID-19 Era” refers to March 2020–May 2023). The data show how our unemployment rate plummeted from nearly 15 percent down to 3.5 percent, all while open jobs increased nearly threefold; the Great Recession period never resulted in such extremes.

The pandemic era drove executive teams to invent health and safety solutions on the fly. The pandemic led to vaccination controversies; some workers being deemed “essential,” which caused them to take maximum risks with their health; the overnight spike of employees working from home; working parents tending to homebound school children; and the coldness of quick business shutdowns that oftentimes sent people home for good with no severance.

Yet the United States recovered from the pandemic more quickly than other countries, such that many companies couldn’t hire employees fast enough. Many of us still remember rushing to reopened restaurants only to then wait for tables because seating sections were closed due to staff shortages. This began the period that became known as the “Great Resignation.”

These complex changes resulted in both good and bad impacts for the US workforce that will carry over into the next twenty years, as will the economic impact of our federal government’s $5 billion bailout to households, mom-and-pop shops, local governments, schools, and other institutions.2

Economically, COVID-19 hit like an earthquake, suddenly and deeply, and was followed by fast infrastructure reconstruction. Our people-management assignment was to preserve the security of our workforce while matching them to jobs as the number of open jobs changed.

Figure 1: How Disruptive Was COVID-19 versus the Great Recession?

Source: US Census Bureau published data.

But the next twenty years will offer a far more profound, continual, and unavoidable challenge because the actual number of available workers will shrink relative to the number of jobs we will try to fill. And each of our fellow industrialized nations will be sitting in the same sinking boat.

Introducing the Great Gully

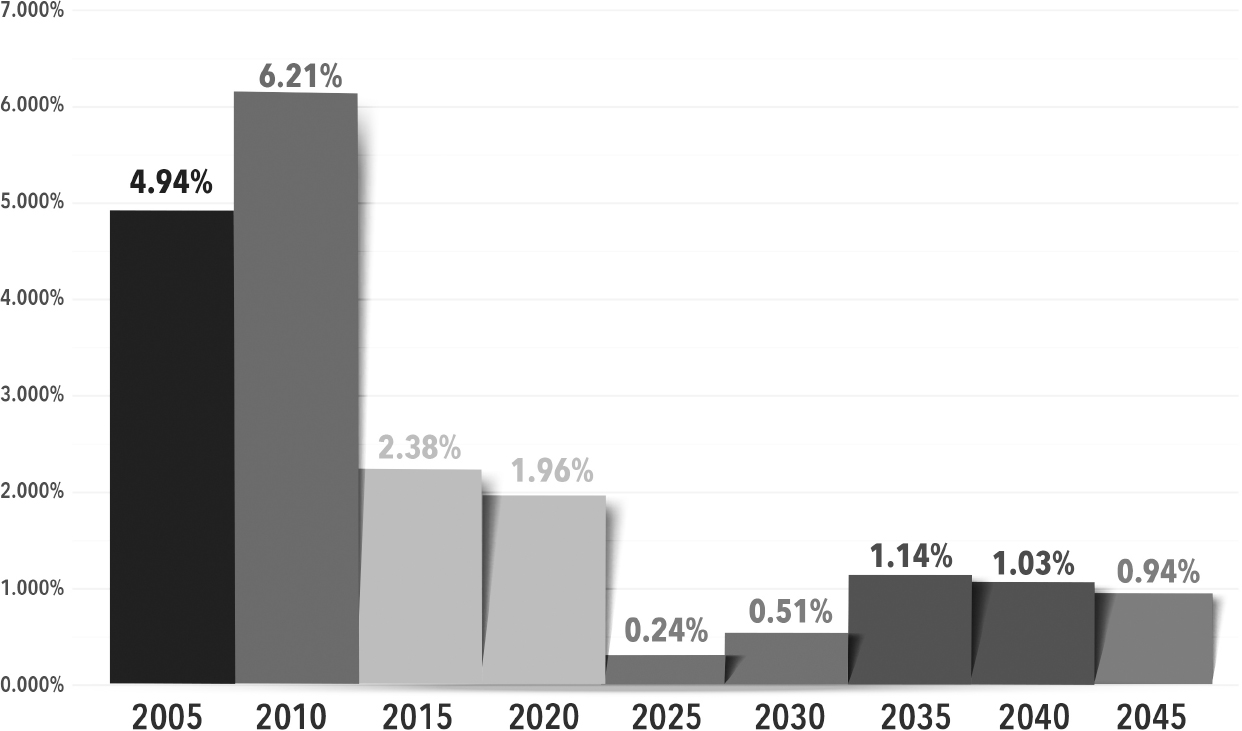

During the past year, I’ve collaborated with the US Census Bureau to learn the measurable impact of massive baby-boomer retirements coupled with our continuing low birthrate. We focused on the number of future Americans in the age group of eighteen to sixty-four, those of working age. Figure 2 depicts what I’ve named the “Great Gully” and compares the percentages of new additions to this group, looking backward and forward by presenting the data for the most recent twenty years and predicting the percentages for the next twenty years.3

Note that the chart does not predict that the number of working-age Americans will actually decrease by 2045—that will come later. Instead, the chart shows that future increases will be small fractions of the increases seen in the past. All of which invites the following question: Can the United States maintain its global economic dominance in the next twenty years and beyond while our number of working-age citizens remains relatively flat?

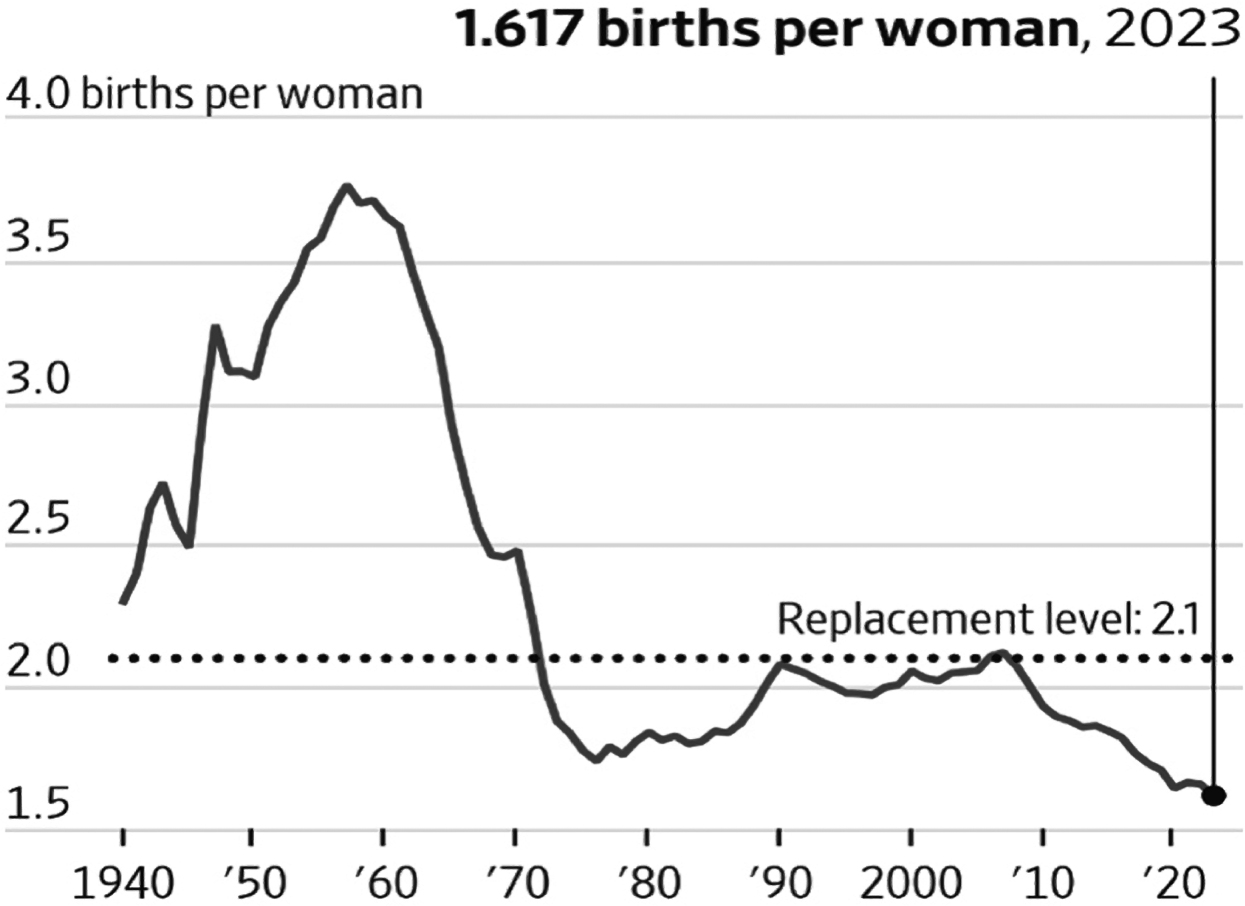

The Great Gully’s projections are based in part on the chart in Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows US birthrates over the most recent eighty-plus year period, with each year measured against the “replacement level” of 2.1. The replacement level indicates that each woman would have to give birth to an average of 2.1 babies during their lifetimes for our population to remain even.

Figure 2: The Great Gully: US Five-Year Growth for the Working-Age Population versus US Annual Growth

Source: US Census Bureau published data.

Figure 3: US Total Fertility Rate

Source: The Wall Street Journal. Used with permission of Dow Jones & Company, Inc., from The Wall Street Journal, Eastern Edition, April 25, 2025; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

The chart tells two different stories: before and after 1972. In the years before 1972, we see the following:

- The data reaches a high point in the early 1950s, when the United States settled into post–World War II normal living, when partners found each other and committed to raising traditional American families after delays imposed by the war.

- Marriages were more stable then and couples routinely had three or four children, unlike today.

- Most interesting to me is the vast gap between the number of babies born per woman during the World War II years of 1941–1945 as compared to the present time. Women were giving birth to about two times the number of children that are born today—and were doing so while the country was at war.

One wonders how this can possibly be true, yet it further underscores the relative scarcity of babies being born today. The Census Bureau in fact predicts that, for the first time in our history, older adults will outnumber children by 2034.4

This high-spiked period spawned a baby boom, and those born during the span of 1946 to 1964 became known as “baby boomers.” As I write, our oldest baby boomers are seventy-nine and our youngest are sixty-one. Over thirty million Americans will reach the typical retirement age between 2024 and 2030, representing nearly 20 percent of our total workforce who are eligible to exit. That’s a devastating number of likely workforce exits.5

After 1972, almost all of the years are below the replacement rate, culminating in the lowest-ever birthrate in 2023. Studies indicate that the rate couples are having kids has greatly slowed because of more women in the workplace, fewer people getting married, and the high cost of parenting, with one study declaring the main reason couples aren’t having kids is “not wanting them.”6

Given that 2023 was the year the United States experienced its lowest-ever birthrate to date and that the birthrate has been in free fall since 2008, there is no cause for optimism here. And recent reports indicate that our marriage rate is also declining, while just 14 percent of single Americans say they are looking for a partner.7 And Americans across all ages are having less sex.8

If we are waiting for a revival spike of more American births, the cavalry isn’t coming. Instead, the Census Bureau predicts the continuing impact of low birth rates will push our total population to actually decline by the end of this century.9 The population peak year will be 2080 and then it’s downhill from there. How will that impact the United States’ global economic position and power?

COVID-19 Further Reduced the Workforce

This demographic pattern of baby boomers leaving the workforce and there not being enough kids produced to replace them has long been a slow-burning, pig-in-the-python fuse. Demographers decades ago predicted a future worker shortage, and that time is now. What could not have been predicted is that the pandemic took even more workers away, making a bad situation much worse.

In 2022, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell announced there were 3.5 million fewer people in our workforce compared to pre-pandemic times.10 He attributed most of these reductions to unplanned retirements as about two million older Americans unexpectedly walked away from their jobs shortly after the pandemic hit. COVID-19 deaths have also contributed as nearly 275,000 of COVID-19 deaths have involved Americans in our working-age group of eighteen to sixty-four.11

When I asked my Census Bureau contact if their projections accounted for these unexpected COVID-19-era losses, he replied, “Some, but not all.” So the decreasing workforce data presented in the Great Gully chart (Figure 2) might actually be worse.

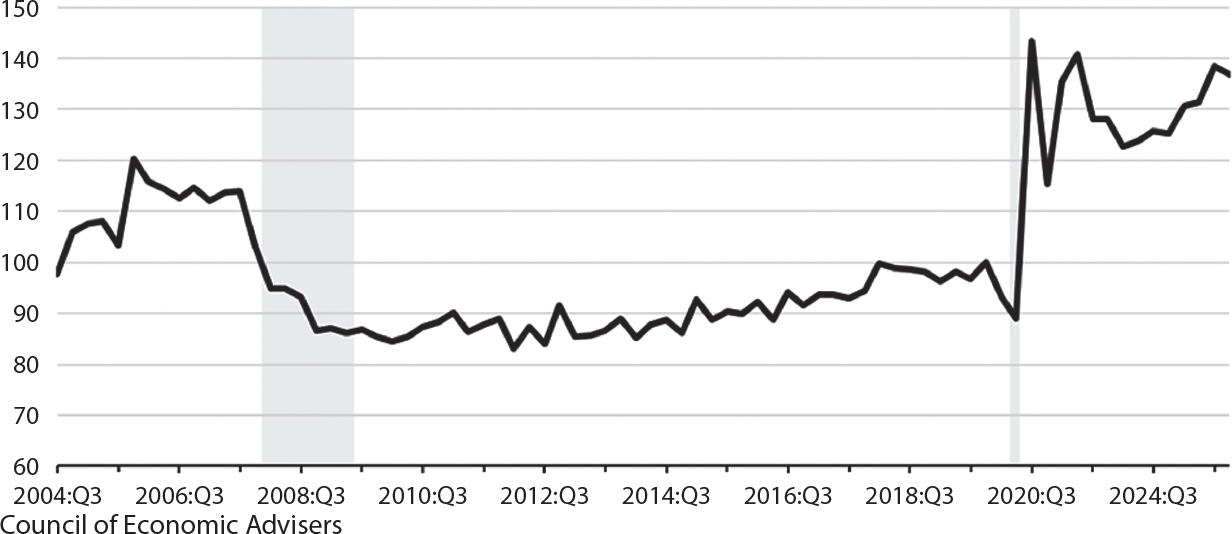

But perhaps the greatest drain on our numbers of workers from the pandemic has been the volume of former employees who have now cast themselves as entrepreneurs. Many of these are self-starting, long-hour workers who continue to contribute to our society but have separated themselves from the corporate world—and therefore from ever having bosses. Note how their historic growth mirrors the down-and-up impact of the pandemic.12

The data in Figure 4 represent only those who started businesses that require or benefit from paying for a government business license and who intend to hire workers. They omit, for example, our four-million-plus Uber and Lyft drivers, dog-sitters, and other gig economy workers who now disregard online job postings because they have sworn off big-business or so-called establishment jobs. And there is little reason to believe gig workers will return to establishment jobs as those companies will be outsourcing more work to gig workers because they won’t find employees to put on their payrolls to do that work.

Put yourself in the place of a restaurant server in 2020. When the pandemic hit, you were instantaneously “furloughed” in March with likely no pay and then invited back when restaurants reopened a year later. Government money kept you partially afloat but landscaping work, delivering food, or dog-sitting contributed to needed cash flow. Or maybe you took online courses to chase an interest or prepare for a better job. When your restaurant called a year later, you refused to return to a job that required working holidays, cleaning floors after midnight, and other aspects of restaurant-server jobs that most of us take for granted. In that interim period, you had become an entrepreneur who didn’t require a business license.

Figure 4: US Total Monthly Business Applications for Likely Employers

Sources: US Census Bureau and Council of Economic Advisors calculations. Permission to reproduce.

Note: Number of applications is indexed to 2019 Q4. Employment-generating business applications are high-propensity business applications (HBA) as defined in the Census Business Formation Statistics. Gray bars indicate recessions.

This is why we had to stand in line waiting for tables after restaurants reopened. Those former servers had found better lives.

I recall reading about a mid-forties healthcare executive who said his greatest COVID-19-era joy while working from home was taking his two daughters to soccer practice. He subsequently quit his executive hospital job and became a self-employed consultant. He will still show up in federal workforce data as employed, but he is no longer available to any hospital or healthcare organization as a full-time employee.

COVID-19’s Impact on Worker Preferences, Attitudes, and Grit

This same era gave birth to “quiet quitting,” “work your wage,” and other commitment-reducing terms, as well as pushed employees’ interests forward regarding working from home and four-day work weeks. About 40 percent of our jobs can be done from home, which equates to sixty-seven million of them, and CEOs have vacillated on their return-to-office requirements lest they face the risk of added turnover. Twenty years ago, CEOs would say, “Jump!” and employees would say, “How high?” but not so today because the scarcity of workers gives them the power to swing decisions.

Certainly related is Gallup’s reporting in 2024 that employee engagement was at an eleven-year low, and the drop was particularly acute among remote, hybrid, and younger workers.13 Added to this are reports that young workers don’t want the additional responsibilities that come with promotions, and that excessive numbers are ghosting job interviews as well as their first days of work.14

Much has been written about young workers’ mental health since the pandemic, with the American Psychiatric Association reporting in 2023 that over half of young professional workers said they needed mental health help in the past year.15 Reasons cited were the enormous growth of social media, political and cultural divisiveness, and unprecedented upheaval and change related to the pandemic. In addition, record numbers of young adults are living with their parents, bringing into question if this will further erode our workers’ social and take-on-responsibility skills.16

The pandemic also left a negative trail with our children. Having missed out on traditional schooling, test scores are substantially down, absenteeism has nearly doubled, and homeschooling has seen an unprecedented surge.17

Gluing together young Americans’ trends like more mental health issues, more adults living with parents, more absenteeism, less employee engagement, and less interest in relationships calls into question whether excessive social media has pushed our youth to be more distant and generally less involved, both in their work and in the lives of others.18

The baby-boomer generation they are replacing has been known for its workplace grit: arriving daily and on time, remaining until the work was done, and staying longer with each employer. COVID-19 created a massive interruption in young people’s lives, and our nation looks forward to them thriving beyond all of the related setbacks as they move forward. With fingers crossed.

Middle-Age Wanderlust

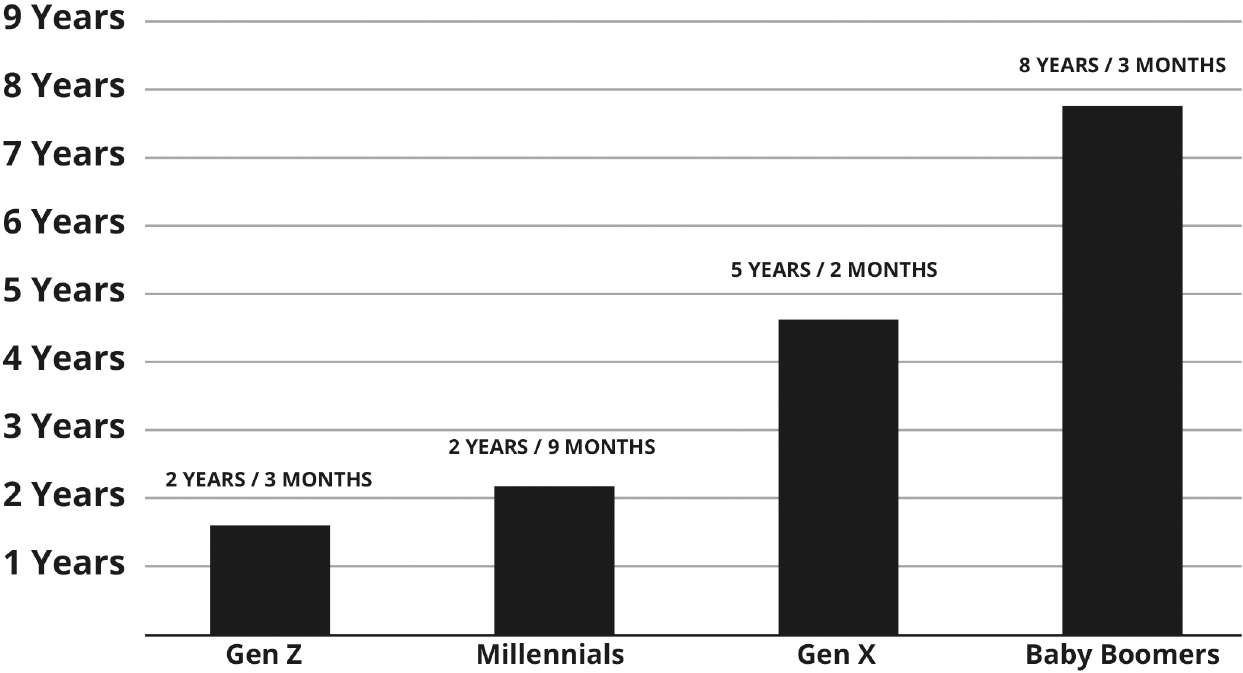

Making things even worse, baby boomers are taking with them their just-a-few-jobs-for-life histories, which predicts worse employee retention for the future. Figure 5 makes clear that younger generations are staying with employers for far shorter periods of time than the older ones did.19

For reference:

- Gen Xers were born during the period of 1965 to 1980.

- Millennials were born during the period of 1981 to 1996.

- Gen Zers were born during the period of 1997 to 2012.

Many apply the term “millennials” to young people in general, yet, in reality, those millennials are now middle-aged or close to it. Some of us have wondered if millennials could maintain their short job stints as they grew older while taking on families and other financial responsibilities. But the workforce shortage will further accommodate them in changing their day jobs while working their gig jobs by night. So, as baby boomers eventually move completely off the above chart, the time in the same job for the remaining generations will likely become even shorter.

Figure 5: Average Length of Employment by Generation

Source: CareerBuilder published data.

Companies Are Already Desperate for Talent

It’s become common to complain about poor customer service and to hear the “things aren’t like they used to be” mutterings of those with clear memories of right-in-front-of-me employees who were always eager to help. And those who mutter are right because a full 75 percent of American businesses have already turned away customers or cut operating hours because they can’t hire enough staff, making us wonder how much worse can customer service become.20 Here are just a few examples that cut across many industries:

- Airlines are closing off routes due to pilot shortages while national safety experts are monitoring whether airlines are promoting junior pilots to bigger planes too quickly.21

- CVS, Walgreens, and Walmart have all reduced their pharmacy hours in the midst of a pharmacist shortage, and this is happening while public opinion of brick-and-mortar pharmacies is sinking fast.22

- A new hospital in Phoenix stood empty for six months because administrators couldn’t find enough staff to provide services to patients.23

- School bus-driver shortages are forcing parents to drive their children to school, brought on by more flexible driving opportunities with Amazon, Uber, and other employers.24

- Parents also struggle to find childcare as 150,000 childcare workers have moved on to other jobs since before the pandemic.25

- Private and public sector employers are scaling back on college requirements, focusing instead on actual skills required for their jobs—and reducing the value of a college degree.26

On the legislative side, at least eleven states have sought to loosen their child labor laws. Iowa, for example, wishes to allow children as young as fourteen to work in meat coolers and industrial laundries, whereas lawmakers in Wisconsin believe those same fourteen-year-olds should be able to double as cocktail waitresses at night.27

On the military side, the US Army is offering up to $50,000 in hiring bonuses for qualified civilians, while the US Air Force has modified its fitness requirements by raising the acceptable levels of body fat.28 The US Air Force just got fatter in order to better find and retain recruits.29

In my own county north of Orlando, officials are urging us to drive our own recyclables to the dump because they can’t find and retain enough garbage truck drivers.30 And our sheriff just lowered the age for jail detention officers from twenty-one to eighteen to fill open jobs.31 The convicts they are guarding will benefit from our worker shortage too, as businesses are opening their doors to ex-cons, saying more than 80 percent of them are performing their jobs the same or better than other workers.32

Is Technology a Fix?

Remember when we feared that robots would take away all of our jobs, plunging America into high unemployment? Now we can’t get enough of them to help keep our businesses afloat. Here are just a few of the bot inventions that are reducing the need for real people:

- Self-check-out technology in grocery stores, pharmacies, etc.

- Continuously improved ATMs to reduce bank staff and ultimately replace branches

- Automated ordering in restaurants to replace wait staff

- Purchasing online, which removes the sales rep

- Robo-calling telemarketers, whether we like them or not

- Robots that gather products in distribution centers, build cars, assist with surgeries, and more

- Self-driving cars and trucks, including commercial vehicles

And Avis, my Jamaican-born dry cleaner rep, has been replaced by a smooth-talking British-sounding female robot who instructs me on how to get my clothes cleaned, 24/7.

Of course, these robots require workers to design and develop them, which brings to mind this assessment from the Brookings Institution regarding AI’s impact on job addition and subtraction:

On one hand, automation often creates as many jobs as it destroys over time. Workers who can work with machines are more productive than those without them; this reduces both the costs and prices of goods and services, and makes consumers feel richer. As a result, consumers spend more, which leads to the creation of new jobs.33

The Inevitable and Unpopular Immigration Solution

Let’s glue together these two very conflicting data sets. The US Census Bureau tells us that, beginning in 2030, 51 percent of our new working-age entrants will be immigrants, having been born outside of the United States, and this immigrant percentage will increase each year for as far as the Census Bureau projects. Here’s their specific language: “Beginning in 2030 . . . immigration is projected to overtake natural increase (the excess of births over deaths) as the primary driver of population growth for the country.” They go on to describe the 2030s as a “transformative decade for the U.S. population.”34 Yet US citizens’ emotions about immigrants are not so welcoming, as Gallup’s most recent polling says 55 percent of Americans want less immigration, while just 16 percent want more.35

Americans’ opinions on immigration come as no surprise, perhaps based on media coverage of our Mexican border. The Carnegie Corporation has dug in on common perceptions about immigrants by providing facts versus commonly held perceptions. Here are a few of those misperceptions:

- Myth #1: “Immigrants will take American jobs, lower wages, and especially hurt the poor.”

- Myth #2: “It is easy to immigrate here legally. Why don’t illegal immigrants just get in line?”

- Myth #3: “Immigrants abuse the welfare state.”

- Myth #4: “Immigrants are a major source of crime.”

- Myth #5: “Immigrants pose a unique risk today because of terrorism.”36

Few Americans would guess the disproportionate roles immigrants played in our surviving COVID-19: the US pharmaceutical companies that developed vaccines were founded by immigrants, and a disproportionate number of all US healthcare workers were born outside of our country.37

Record numbers of immigrants have entered our labor force since the pandemic, and, more importantly, 68 percent of them are working or seeking work, compared to just 62 percent of native-born Americans.38

The Global Workforce Population Conundrum

As noted earlier, the US population will begin to decrease in 2080, while the amount of working-age Americans will decrease before then.39 This might cause economists to predict doom for the US homebound economy—except for the fact that all our high-income industrial competitors are heading in the same direction.

Country-specific data is astounding. The German working population will reduce by a third by the end of this century; Italy, Spain, and Greece will lose half of their total workforces; and Poland, Portugal, Romania, Japan, and China will all lose up to two-thirds of their labor force.40 Another report details that by as soon as 2030 the world will be short by eighty-five million workers, the approximate population of Germany. Six million of these shortages will be in the United States.41

Sampling national responses, Germany has legislated an immigration skill-based point system, South Korea is considering paying a $70,000 bonus for each newborn child, while Japan has rejected immigration as a fix and is instead implementing “womenomics,” asking more of their women to join their workforce.42

Russia’s baby-shortage solution is quite different, where the minister of health for the region of Primorsky Krai instructed that having a busy career wasn’t an excuse for not having a family, and that people could choose to “create offspring” during work breaks.43 There was no mention of wine or candles.

South Korea’s birthrate has fallen to the world’s lowest, resulting in sales of dog strollers outselling sales of baby strollers. The then president declared this to be a national emergency, all while he and his wife had no children but ten cats and dogs.44

The driver again is low birthrates, and global birthrates vary greatly among nations and income levels. These data on 2022 birthrates come via the World Bank.45

Selected birthrates by region:

- Arab world: 3.1

- Australia: 1.6

- East Asia and the Pacific: 1.5

- European area: 1.4

- Latin America and the Caribbean: 1.8

- North America: 1.6

- Sub-Saharan Africa: 4.5

Higher birthrates are mostly found in the poorer countries, as the rate for “Heavily indebted poor countries” is 4.5 and for “Least developed countries” is 3.9. Plus, those they classify as “low income” had a 4.5 average birthrate whereas those who were “upper middle income” had an average of just 1.6. All of which leads to this ultimate population projection by the World Bank: “By 2100, 5 of the 10 most populated countries are projected to be in Africa.”46

As we progress deeper into this century, the race will be on for developed nations as they compete against each other for immigrant talent. And those same competitors will likely invest in Africa to develop skilled workers for both there and abroad.

In Closing, the “War for Talent” Was a Snowball Fight

In 2001, a group of McKinsey consultants authored a book called The War for Talent.47 I had just worked with two of those authors on a project with my then-current company, so I was eager to see what these same consultants had to say about talent. My copy still sits in the bookcase next to my desk.

The authors detailed initial doubts about using “war” in their title due to its militaristic tone, but later concluded their title “vividly captures the new realities of the talent market.”

Ten years later, Gallup CEO Jim Clifton wrote another jobs-related book and named it The Coming Jobs War, describing his book this way:

The war for global jobs is like World War II: a war for all the marbles. The global war for jobs determines the leader of the free world. If the United States allows China or any other country or region to out-enterprise it, out-job-create it, out-grow its GDP, everything changes. This is America’s next war for everything.48

There are few companies I respect more than McKinsey and Gallup. I’m confident those same authors would agree that we are now facing a much higher, unprecedented wall regarding the absence of workers that will continue standing for the remainder of our lifetimes.

Five Summary Thoughts for the Next Twenty Years

- There will be even fewer workers and more help-wanted signs, whether created by AI or magic markers, summarized by this US Census Bureau quote: “By 2034, we project that older adults will outnumber children for the first time in U.S. history.”49

- While most talk will be about worker quantity, worker quality will also take center stage as both will be required for businesses to stay in business.

- Given young worker trendlines, retaining them for two years or even six months will require fresh thinking versus traditional employee surveys that lead to one-size-fits-all programs and thinking.

- More immigrants will become visible on all job levels. Visit Toronto to envision this in a high-income, mainly English-speaking city.

- Worker shortages will become the dominant driver of all economic trends by becoming the foundation for increased inflation, supply chain woes, and more because businesses cannot make products cost-effectively and on time without good workers.