Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Antiracist Heart

A Self-Compassion and Activism Handbook

Roxy Manning (Author) | Sarah Peyton (Author) | Shakti Butler, PhD (Author)

Publication date: 08/29/2023

Have you wanted to stand up for the values you believe in, yet found yourself inexplicably held back? Do you long for a way to hold people accountable that doesn't simultaneously demean them? The Antiracist Heart combines cutting-edge neuroscience with ways to build Martin Luther King Jr's vision of Beloved Community, delivering practical tools for the internal and interpersonal work of antiracism. This book prepares the reader to have a new kind of conversation when racist harms occur one that doesn't shy away from hard truths yet doesn't demonize anyone.

Based on the framework of How to Have Antiracist Conversations, the activities in this handbook empower readers to disrupt the ways racism plays out in daily life. In each chapter, Manning, a clinical psychologist and antiracist activist, and Peyton, a neuroscience expert and educator, both trainers in Nonviolent Communication, unpack key concepts like bias and trauma using brain science alongside practices for self-connection and dialogue.

The exercises are:

- Flexible

- Designed to work for individuals or groups

- For people of the Global Majority (BIPOC) or white people

- For those with or without experience in addressing the effects of racism

By better understanding the neuroscience of how brains develop in response to culture, readers gain skills to interrupt implicit biases and racist constructs deep within the brain. The activities invite introspection and a radical form of self-compassion that make antiracist dialogues and actions possible, thus creating real change.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Have you wanted to stand up for the values you believe in, yet found yourself inexplicably held back? Do you long for a way to hold people accountable that doesn't simultaneously demean them? The Antiracist Heart combines cutting-edge neuroscience with ways to build Martin Luther King Jr's vision of Beloved Community, delivering practical tools for the internal and interpersonal work of antiracism. This book prepares the reader to have a new kind of conversation when racist harms occur one that doesn't shy away from hard truths yet doesn't demonize anyone.

Based on the framework of How to Have Antiracist Conversations, the activities in this handbook empower readers to disrupt the ways racism plays out in daily life. In each chapter, Manning, a clinical psychologist and antiracist activist, and Peyton, a neuroscience expert and educator, both trainers in Nonviolent Communication, unpack key concepts like bias and trauma using brain science alongside practices for self-connection and dialogue.

The exercises are:

- Flexible

- Designed to work for individuals or groups

- For people of the Global Majority (BIPOC) or white people

- For those with or without experience in addressing the effects of racism

By better understanding the neuroscience of how brains develop in response to culture, readers gain skills to interrupt implicit biases and racist constructs deep within the brain. The activities invite introspection and a radical form of self-compassion that make antiracist dialogues and actions possible, thus creating real change.

-Edmundo Norte, Dean Emeritus, Intercultural and International Studies, De Anza College, and Senior Fellow, Community Learning Partnership

Manning and Peyton have contributed a practical how-to guide and toolkit for folks across the full spectrum of antiracist dialogues. Nobody is left out. Everyone is seen and has a place. What makes this rare and much-needed book so useful and path-breaking is that it brings together different strands from Nonviolent Conversation, psychology, and authentic dialogues to show us all a courageous path forward for healing, antiracism, and creating Beloved Community.

-Karen DeGannes

The insights and practical strategies shared within these pages have had a profound impact on me both personally and professionally. Within hours of applying the book's teachings, I felt a sense of relief and renewed energy to take meaningful, guilt-free action toward making our world a more just and caring place for all.

-Jane M Connor, MA, MS, PhD, marriage and family therapist, psychologist, and Associate Professor of Human Development Emerita, Binghamton University

If you've ever struggled to make sense of the charged landscape of race, racism, white

supremacy, and antiracism, read this book. If you longed for more clarity, skill, and confidence to address racism and white supremacy, read this book. If you want more meaningful authentic dialogue, read this book. Integrating their deep insight and compassion, Roxy and Sarah offer us a powerful guide to transformative conversations about race.

-Oren Jay Sofer, author of Say What You Mean and Your Heart Was Made for This

1

Toward Beloved Community

Our goal is to create a beloved community and this will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.

—MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., 1966

ANTIRACISM CONCEPT

Beloved Community

Our understanding of antiracism—and the thrust of this entire handbook—is indebted to Martin Luther King Jr.’s references to “Beloved Community” as a goal for all of humanity. Though Dr. King did not originate this term, he embraced it as a key message. The vision of Beloved Community we hold is a vision of the radical inclusion of all human beings.9 Beloved Community asks us to imagine that each person we encounter is a cherished member of our family. We want them to thrive as much as we want ourselves to thrive.

In this Beloved Community, just like in an ideal family, we are fiercely committed to the ongoing examination of the systems around us, to ensure they are meeting the needs of everyone, not just ourselves. In an ideal family, parents make sure their children are fed; they would not attend only to their own hunger. If we saw a family member doing so—letting their children or siblings or grandparents go hungry while they fed themselves—we would pay attention and try to address the situation. We would put our efforts toward helping feed the hungry child and work with the parents to remove any barriers so they could manifest the care that we trust is there. In Beloved Community we seek to create a new status quo: a status quo of genuine mattering, generosity, and interdependence. In Beloved Community our goal is an unflinching willingness to show up authentically and have difficult conversations as often as necessary to restore true well-being and harmony. As we try to fix broken systems and address inequities, we commit to persevere in dialogue, from a compassionate stance, until we arrive at strategies that truly work for all.

The idea of Beloved Community is grounded in our interdependence. As Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in Letter from Birmingham Jail: “I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states…. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”10 As we adopt the consciousness of Beloved Community, we move closer to an antiracist society. We recognize that even if we have benefited from white supremacy culture and other systems of social inequality that privilege some of us, we are never fully thriving if other folks are being left out. We recognize that even as we work to challenge these structures and free our communities from the constraints of white supremacy ideology, we can only be free when all communities are free.

Now that we have more of an understanding of Beloved Community, the question arises: Do we actually want it? The “Do I Actually Want Beloved Community?” questionnaire allows you to inquire into this for yourself. The answers are not scored as they are quite deep and tend to evolve in complexity over time. This questionnaire can be revisited many times and can help us see the development of our commitment to a different world.

QUESTIONNAIRE

Do I Actually Want Beloved Community?

□ Does the impact I’ve experienced or witnessed from systemic racism block me from even wanting to consider the humanity of those who have embodied white supremacy culture and taken harmful action, consciously or unconsciously?

□ Is there anyone I see as outside my community, and as irredeemable?

□ If so, do I like living this way?

□ Is there anyone whose actions or behavior I find unquestionably evil?

□ If so, does this take a toll on my body that I’m tired of?

□ Do I believe that my liberation and the liberation of my community depends on everyone thriving? On everyone mattering?

□ Do I value connecting to the shared needs motivating all behaviors, even those I find challenging?

□ Do I want a more expansive vision of what is possible?

□ Can I envision a world where things are very different, and am I willing to work for it, and even to live it, while the world continues to be in chaos and turmoil?

□ Am I willing to take action aligned with my vision, even if I might not be the one to harvest the fruits of that action?

Assuming the answer to the question of wanting Beloved Community was at least a tentative or qualified “yes,” what is next?

The work to dismantle racism and create truly equitable societies occurs in several spheres. We must change the policies and structures that prop up racism. In Stamped from the Beginning, Ibram X. Kendi demonstrates compellingly how racist ideas emerged to justify the policies enacted out of the self-interest of European traders, thereby formulating the societal institutions and structures that perpetuated social inequality. In order to end racism, he argues, we need to eradicate racist policies.11 Antiracist efforts aimed at changing policy are essential. The work does not stop there, however. All too often, those involved in policy work have an us versus them stance fueled by a scarcity mind-set. Instead of working together to create better conditions for all, some groups fight bitterly to secure and maintain their bit of the pie at the expense of other groups. The disclosure in 2022 of racist, anti-Black remarks by Latine members of the Los Angeles City Council was a dramatic example of this. The news service Vox reported that the racial remarks were fueled by a “desire to siphon power away from Black Angelenos and other minority communities to ensure … a ‘little Latino caucus of, you know, our own.’”12

Consciously choosing how we relate to each other, as we do the necessary advocacy and policy work to create systemic change, goes hand in hand with antiracist work. Without a clear vision of both how we can be in community together across differences and what we are working toward, we are likely to still operate on prevailing social norms based on white supremacy culture. Beloved Community offers an alternate vision that counters the values of white supremacy culture that we can use to guide our conscious behaviors and choices. Something that helps us connect with our own desire for Beloved Community is an understanding of human needs—the values and physical imperatives that motivate all human behavior, regardless of our culture or location. For example, unless we are in touch with our needs for inclusion and care, we won’t even know that we would like Beloved Community to exist. It is only by allowing ourselves to feel our own longings for everyone to belong and remembering our interdependence that we will be able to create ongoing strategies and policies that are inclusive and potentially win-win.

JOURNALING PROMPT

Your Own Beloved Community

Look at the “Needs and Values” chart in the Appendix (Figure 6). Describe the world you would like to live in. For example, how would people deal with conflict or make decisions? What would belonging look like, and how would people know they belonged? Which needs feel most important to you when you think of Beloved Community?

Holding your particular dream of Beloved Community in mind, let’s look at the importance of belonging for human neurobiology.

NEUROSCIENCE CONCEPT

Inclusion versus Exclusion

The need for belonging is so profound that it shapes our entire human experience. It affects how well we read one another’s emotions, how quickly our hearts beat, what our body temperatures are, how often we get sick (and how quickly we get well), and whether we can relax, digest, play, work, and create. When we have a strong sense of belonging, mattering, safety, and welcome, we have an easier time understanding others, and our heart rates calm and become responsive to laughter and to sadness. Our body temperatures cool because we get to share our body heat, we get fewer colds and recover more quickly, we fully digest our food, and we can move seamlessly between play, work, and creativity.13

Every person and organization can have an effect. Each small gathering of people is a fractal of the larger whole; the larger whole is comprised of the many millions of smaller gatherings. Our families, communities, schools, hospitals, places of worship, workplaces, and government agencies can reassess what equitable inclusion and participation look like. Instead of working to ensure that people from the Global Majority gain access to spaces that were previously reserved for white people (and the colonialist, white supremacist, patriarchal, and ableist rules that govern those spaces), we can open ourselves to being in the work of re-creating together what our spaces should look and act like.

If we either only attend to the needs of white people or if we (prematurely) hope we already live in a postracial world, the social systems we engage in (health care, legal, economic, electoral, etc.) may default into the unconscious (or sometimes quite intentional) deprioritization of the Global Majority. White people and Global Majority people can act from this default programming. Even those not intending to do so may—unless they consciously pay attention to who they choose, serve, hire, and promote (and who they are assuming is the audience for their services)—unconsciously favor people who look and sound like themselves (the in-group) and harm people who don’t (the out-group).

ANTIRACISM CONCEPT

Recognizing Violence

Since noticing violence is the first step in interrupting and ending violence, let’s explore what violence is. Many people assume violence is limited to physical actions (e.g., hitting someone) or verbal expressions (e.g., yelling, cursing). These actions are a small subset of the ways violence presents. Think of violence as the negative impact we experience from a person or group’s attempt to address their unmet needs. Violence can occur intrapersonally (on ourselves), interpersonally (between individuals), and structurally (through systems and practices). Depending on our history, we may find it easier to recognize violence when it occurs in one sphere but not in another. For instance, an adult who had very critical parents and internalized their own harsh inner critic may be sensitive to and guard against interpersonal violence. But they might not assess their own derogatory self-talk as violence, instead arguing that such talk motivates them to do better.

Similarly, we often can recognize structural violence—harm to individuals and groups arising from the institutions and practices governing a community—when it impacts us but not pick up on examples of structural violence that impact others. For instance, the administration and staff at a school, some immigrants from non-English-speaking countries, recognized language comprehension was a barrier to equity. They carefully translated materials and had interpreters present at all events to reduce barriers to comprehension that excluded some families. They were less able to recognize and modify other practices that also excluded some families. The school’s tradition of dressing up for “Community Spirit Day” meant families with less economic resources often did not have the capacity to purchase costumes, resulting in their children’s exclusion from the very activities designed to increase inclusion and belonging.

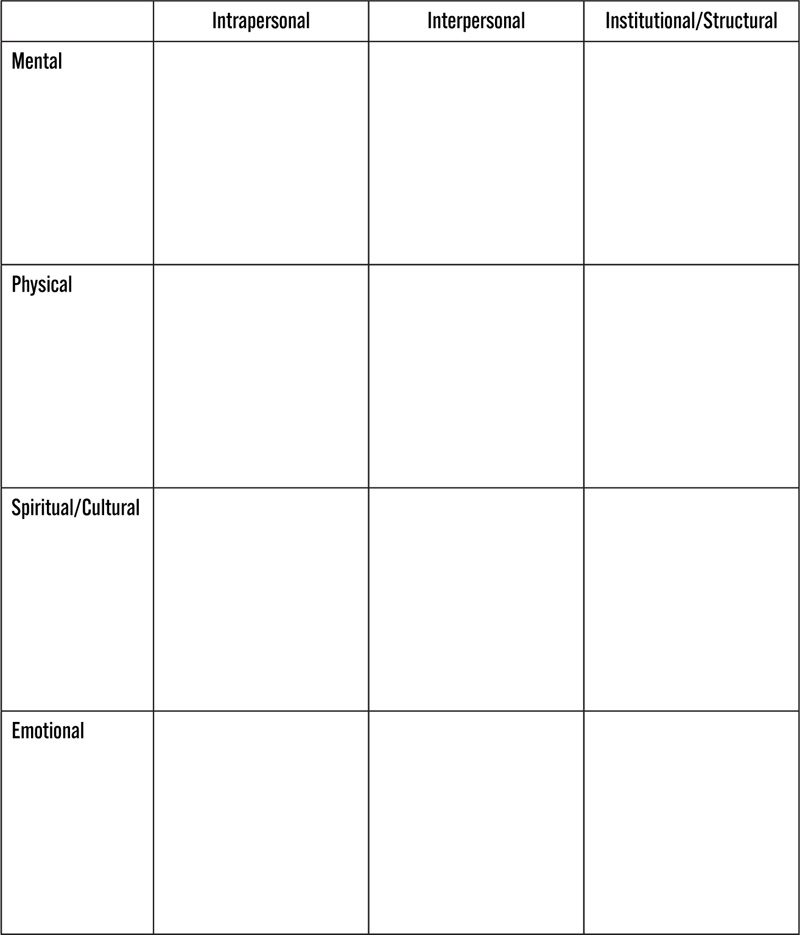

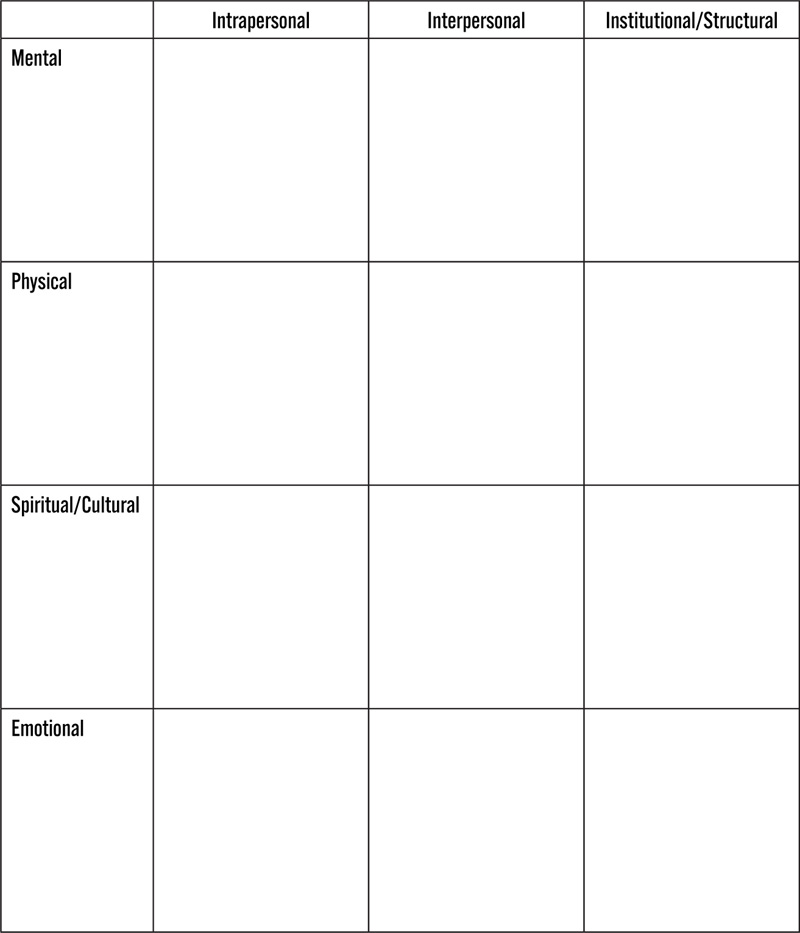

Violence can impact us physically, emotionally, mentally, or spiritually. Our colleague, Edmundo Norte, combines these four aspects of human experience often described in Indigenous traditions and represented through the Medicine Wheel with the three areas of influence (intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional).14 Roxy has combined forms of violence with Norte’s integrated model. Most people readily recognize examples of physical violence occurring at each level (e.g., self-harm, negative self-talk, or substance abuse at the intrapersonal level; fist fights or sexual coercion at the interpersonal level; and voter suppression, war, or genocide at the structural level).

Other forms of violence are not always as easily identified. Mental violence at the intrapersonal level is often dismissed and indeed can be encouraged by capitalist entities. The mindless consumption of media exemplifies a form of intrapersonal mental violence in which many of us engage. If you’ve ever felt depressed over lost productivity after what you intended to be a quick online search for information somehow turned into an hour of scrolling Facebook, you might be experiencing the effects of intrapersonal mental violence. We might participate in structural violence when we enforce policies that result in harm to others. One example is school lunch shaming, when adult workers enforce rules that deny food or food of their choice to schoolchildren with unpaid lunch bills by throwing away the food rather than letting the child eat it.15

WORKSHEET

Recognizing Violence in Our Lives

We regain choice and capacity to care for ourselves when we recognize how violence impacts us. In this worksheet you will explore impact both as the person impacted by violence and the person who enacted violence. Almost all of us, regardless of the identities we hold, have experienced being in both positions. As you complete the “Recognizing Violence in Our Lives” worksheet, notice where it is easier to recognize violence. Think about the words, behaviors, and policies you have encountered that have resulted in unmet needs for you. See if you can identify an example in each category.

Examples of Violence I Have Experienced

Now think of words or actions you have engaged in (including upholding policies) that negatively impacted others. If you are unable to think of a time when you have enacted violence, consider asking people you trust to authentically share with you the impact they may have experienced. Use of this framework may become clearer as you work with the material in this handbook.

Examples of Violence I Have Enacted

ANTIRACISM CONCEPT

Choosing Nonviolence

In his biography of Mahatma Gandhi, Eknath Easwaran wrote: “Satya and ahimsa, truth and nonviolence, became Gandhi’s constant watchwords. In his experience, they were ‘two sides of the same coin,’ two ways of looking at the same experiential fact…. Ahimsa does not contain a negative or passive connotation as does the English translation ‘nonviolence.’ The implication of ahimsa is that when all violence subsides in the human heart, the state which remains is love. It is not something we have to acquire; it is always present and needs only to be uncovered.”16 Nonviolence, as practiced by Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who was inspired by Gandhi, involved an intention to do no harm. This is a grounded, thoughtful approach to nonviolence rather than an unconscious contract. This commitment is grounded in the awareness that harm can happen through positive action as well as through inaction. When we knowingly choose actions or fail to respond to actions that we are aware will result in harm, we are consciously choosing not to act in alignment with nonviolence. Why might we do this?

Nonviolent Communication invites us to hold that every action that a person takes is their best attempt, within the constraints of their capacity or awareness, to meet a need. Sometimes we are unable to identify any other way to attend to what we value than to take an action that might harm someone else. Sometimes the impact of white supremacy culture may lead us to devalue, justify, or dismiss the harm that is happening to others. When we choose nonviolence, we are making a commitment to seek other ways to get our needs met that do not harm others. We might choose to resist complying with institutional policies (like redlining) and structures of social inequality (being followed in a store by security because of your skin color) that cause harm. We can be supported in making this choice if we develop a practice of looking at the places where we are causing harm, consciously or unconsciously, and exploring what needs our actions are meeting. We can then attempt to find other strategies that can better meet our needs.

Consciously or unconsciously, as we move through life, we will take actions that result in harm for other people. Later in this handbook, we will discuss what to do when we recognize that someone has been impacted by our actions, whether those actions were intentional or unintentional. Often, harm occurs without our conscious intention or awareness. Even with the best of intentions, with our firmest commitment to Beloved Community, we can learn that we have impacted someone in a harmful manner. People who attend Roxy’s course on microaggressions often respond with hopelessness. They exclaim: “I won’t ever be able to do anything right” or “I’ll never know what’s going to offend someone or not.” This sense of overwhelm can turn into passivity: “Unless I know and can avoid every possible way someone can receive impact, there’s no point in trying.”

This stance does not liberate us. It is certainly true that there is no way to know everything we must know in every moment to avoid ever stimulating harm. There are several steps we can take to cope with this truth. First, we must accept that there are things we do not yet know and commit to a practice of continuous learning. As I, Roxy, write this handbook and talk with members of my community, I repeatedly become aware of gaps in my understanding and ways I impact others that I did not previously see. Each time, as I stay open to my impact, I gain one more bit of information that will allow me to reduce my impact as I move through the world. As I reflect on my current behavior, I realize I am no longer doing the things I used to do that stimulated pain. Recognizing this helps me trust that with each new awareness, I can learn to do less harm to self and other.

Next, a corollary of the idea that we are continuously learning is that I can commit to a stance of curiosity and humility. Too often, when we are told we have impacted someone, especially when the impact was unanticipated, we defensively question the person. Did they understand what we were trying to do? Are they certain of the impact? Instead, we can remind ourselves: “Sometimes I have an impact I did not intend. I choose to listen and understand more about how this person was impacted and what I can do to support them.” If we accept that harm does happen, despite our best intentions, and that it does not mean we are “bad,” we have more spaciousness to be with the person impacted and with ourselves. Our curiosity and humility afford us the capacity to repair the harm that was done and therefore to do less harm overall.

WORKSHEET

From Violence to Nonviolence

Choose an example of violence you have consciously or unconsciously committed. If you haven’t already, you may wish to complete the “Recognizing Violence in Our Lives” worksheet to identify one.

What is the action or inaction?

What needs were you attempting to meet by that (in)action?

Did you experience harm as the result of your (in)action? If so, describe the harm. What needs were not met for you?

Did another person experience harm as the result of your (in)action? If so, describe the harm. What needs were not met for that person? What needs were not met for you in relation to that person’s experience of harm?

Brainstorm at least one way you could meet your original need that would not result in harm to yourself or the other person.

If you are unable to identify an alternative strategy, reflect on the ideals of nonviolence and Beloved Community. What needs would you meet by choosing not to take action to meet your original need? How would doing so support your intention to work toward Beloved Community?

As you reflect on this practice, are there insights you want to remember to help guide future decisions? Write them here.

NEUROSCIENCE CONCEPT Unconscious Contracts and Beloved Community

As we will see throughout this handbook, the more conscious we are, the more powerful we are. When we experience difficulties alone, we often survive them by making promises to ourselves that we are quite unaware of. This happens because the part of our brain that stores difficult memories, the amygdala, has no sense of chronological time and really wants to protect us from ever making a “mistake” again. So it takes a behavioral response to a difficult event and links it to the frightening stimulus. We can call these habits “unconscious contracts.” Here are some examples:

■ When having to interact with a new boss, after having had a bad experience with a prior instructor, the old contract will come alive again: “I will never trust anyone in authority.”

■ When feeling overwhelmed and being told to ask for support, after having been shamed for being needy as a child: “I will only rely on myself.”

■ When imagining sharing vulnerably, after receiving life-long messages of unworthiness: “I will never let anyone know what I really think.”

If we just stop there, accepting these statements as truth, they seem complete and unchangeable. But if we are able to dig a little deeper, we can discover that each statement is actually an unconscious contract that we’ve made, which links into a past or present difficult event that has simply been a part of our life experience. The way that we are able to do this excavation is with the very simple but powerful phrase “in order to.” For example:

■ “I will never trust anyone in authority in order to protect myself from the betrayal of my third-grade teacher.”

■ “I will only rely on myself in order to keep my heart from being broken as it was when I was eight.”

■ “I will never let anyone know what I really think in order to keep myself safe from my siblings’ ridicule.”

Bringing in the deeper work of “in order to” allows our bodies to communicate to us about what happened in the past—and how we found a way to survive it. Once we have a sense of why we’ve been doing what we do, we can check for truth by adding to the end of the sentence “no matter the cost to myself.” As we say the full sentence, including that last phrase, we pay attention to feeling if our body says: “Yes, that’s what I do.” (Once we are able to fully name the contract and make sense of it within our personal history, we gain a new agency: to release ourselves from the contract, if we are ready.) As we will see, for members of the Global Majority, these kinds of contracts limit expression and a sense of wholeness, as well as the hope that Beloved Community is possible. For white people, these kinds of contracts underpin many of the harmful behaviors associated with white supremacy ideology and limit the capacity for Beloved Community.

QUESTIONNAIRE How Do I Unconsciously Limit Beloved Community?

Many people have unconscious contracts that obstruct Beloved Community. Some of them may involve looking through a lens of right/ wrong or good/bad, where people who act like us are “good” or “right,” while people who appear to be different are judged as “bad.” We may even lose sight of our shared humanity. Becoming aware of our contracts allows us to free ourselves from them and to welcome everyone into Beloved Community. You may wish to put a check mark next to any of these statements that ring true for you:

□ “I will only consider people who see the world the way I do as belonging to my community.”

□ “When I meet people who treat me and others as less than human, I will consider them to be beyond redemption and unworthy of my time.”

□ “I will punish people who do not share my values by cutting them out of my circle of care; they will no longer exist for me.”

□ “I will not value or respect people who do not share my integrity.”

□ “I will not see or include people who look different from me.”

□ “I will not see or include people who have less than me.”

□ “I will not see or include people who have more than me.”

□ “I will believe that Beloved Community is a naive and dangerous concept.”

□ “I will believe that the part of myself that longs for Beloved Community is naïve and misguided.”

As you find the statements that are truest for you, self-compassion is essential. People may find it unbearable to recognize that they believe some of these things, because they judge these beliefs as wrong. This “shame-trap” stops antiracism work in its tracks. If we can be immensely tender with our beleaguered brains, we will be more likely to discover the origin of our beliefs and release ourselves from our contracts. That liberation allows us to engage more effectively in antiracism work. Let’s try adding “in order to” to contracts related to Beloved Community. Here are some examples. Yours may be different.

“I promise myself that I will punish people who do not see the world the way I do by cutting them out of my circle of care in order to have some power in a corrupt world that seems too big for me to change, no matter the cost to myself.”

“I promise myself that I will believe that Beloved Community is a naïve and dangerous concept in order to keep myself safe from hope and heartbreak, no matter the cost to myself.”

“I promise myself that I will not see or include people who look different from me in order to have familiarity and comfort and to be able to think that I understand the world and that it is predictable, no matter the cost to myself.”

Now that you see the possible “in order to’s,” what happens to your self-compassion? What happens to your conviction that these contracts are permanent and unchangeable?

The final steps related to working with unconscious contracts are the release and the invitation. For the release we simply say to ourselves: “I release you from this contract.” Then we add the invitation: “And instead, I invite myself to….” The invitation will make the original contract doable. For example: “I invite myself to claim my power without excluding others,” or “to know that hope and heartbreak are just the human condition, and they will not destroy me,” or “to know and accept that the world is not predictable, but that I can be predictable inside it,” or “to recognize that excluding certain people does not make me safer.”

EXERCISE Release the Contracts That Prevent the Intention to Live in Beloved Community

I, (YOUR NAME HERE), make a promise with myself that I will:

(Insert one of the contracts that seemed true for you from the “How Do I Unconsciously Limit Beloved Community?” questionnaire.)

Then use the “General Worksheet to Release Unconscious Contracts” to release any of the unconscious contracts that feel true to you.

IN CLOSING Taking Beloved Community as Our North Star

These worksheets, exercises, and journaling prompts offer ways to make Beloved Community a shared North Star to guide us toward a better world. Sometimes what we are reaching for is a little better—and sometimes a lot better—than what is happening right here and right now. For this journey we need nourishment, we need inspiration, and we desperately need self-compassion to let our bodies continue to receive support while we access our fierce commitment to creating an antiracist world.

In Chapter 2 we explore the various ways that white supremacy culture affects our capacity to take accountability for our impacts, seeks to squash the power of our righteous anger to fuel change in service of Beloved Community, and keeps us tied up in harmful dual-istic thinking. In addition, we are going to clear the way to bring our anger—even our rage—into alignment with our longing for justice, presence, integrity, and love. Such a shift can give us power.