Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Art of Conscious Conversations

Transforming How We Talk, Listen, and Interact

Chuck Wisner (Author)

Publication date: 10/25/2022

We live in conversations like fish live in water-we're in them all the time, so we don't think about them much. As a result, we often find ourselves stuck in cyclical patterns of unproductive behaviors. We listen half-heartedly, react emotionally, and respond habitually, like we're on autopilot.

This book is a practical guide for thoughtfully reflecting on conversations so we can avoid the common pitfalls that cause our relationships and work to go sideways. Chuck Wisner identifies four universal types of conversations and offers specific advice on maximizing the effectiveness of each:

Storytelling-Investigate the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves and others

Collaborative-Explore the way our stories and other people's stories interact

Creative-See new possibilities and discover unforeseen solutions

Commitment-Make promises we know we can keep

These conversations unfold sequentially: our awareness of our and others' stories transforms our ability to listen and collaborate, which opens our thoughts to creative possibilities, guiding us toward mindful agreements.

Our conversations-at home, at work, or in public-can be sources of pleasure and stepping-stones toward success, or they can cause pain and lead to failure. Wisner shows how we can form a connection from the very first conversation and keep our discourse positive and productive throughout any endeavor.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

We live in conversations like fish live in water-we're in them all the time, so we don't think about them much. As a result, we often find ourselves stuck in cyclical patterns of unproductive behaviors. We listen half-heartedly, react emotionally, and respond habitually, like we're on autopilot.

This book is a practical guide for thoughtfully reflecting on conversations so we can avoid the common pitfalls that cause our relationships and work to go sideways. Chuck Wisner identifies four universal types of conversations and offers specific advice on maximizing the effectiveness of each:

Storytelling-Investigate the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves and others

Collaborative-Explore the way our stories and other people's stories interact

Creative-See new possibilities and discover unforeseen solutions

Commitment-Make promises we know we can keep

These conversations unfold sequentially: our awareness of our and others' stories transforms our ability to listen and collaborate, which opens our thoughts to creative possibilities, guiding us toward mindful agreements.

Our conversations-at home, at work, or in public-can be sources of pleasure and stepping-stones toward success, or they can cause pain and lead to failure. Wisner shows how we can form a connection from the very first conversation and keep our discourse positive and productive throughout any endeavor.

-Doug Field, Chief EV and Digital Systems Officer, Ford Motor Company

The Art of Conscious Conversations is a thought-provoking and practical guide to unpacking conversations at work and in life. Seasoned leadership coach Chuck Wisner shares his personal experiences and compelling stories of others who've successfully used the techniques he shares in this book to encourage us all to approach conversations with curiosity and introspection. A compelling read with a big impact.

-Susan McPherson, author of The Lost Art of Connecting

Conversations are a portal into strengthening our relationships, yet they aren't always treated with the care they deserve. In The Art of Conscious Conversation, Wisner unpacks the key ingredients to having more thoughtful, connected, and collaborative conversations. This is a helpful guide for building better relationships, one conversation at a time.

-Ximena Vengoechea, author of Listen Like You Mean it

What Chuck teaches best is how to use words effectively to reduce misunderstanding and conflict. His easy-to-remember concepts helped me examine my thinking and interactions and transform my conversations at work and at home.

-Vineet Mehta, Director of System Modeling and Battery Technology, Tesla

THE BIRTH OF STORIES

Reality is always kinder than the stories we tell about it.

—BYRON KATIE

We humans have been telling stories for millennia. These stories determine how we relate, parent, work, and love; what we value; and with whom we choose to wage war. They describe who we are (father/son, leader/follower, citizen/immigrant, conservative/liberal). They forge relationships (partnerships, marriages, friendships, colleagues). We entertain and educate one another through them (books, schools, universities, movies, fiction). And they activate our work together (contracts, employment, friends helping friends).

When life is chugging along, our story-making brains work beautifully, and we rarely notice the work that they do. Everything feels right, like home. Right now I’m sipping espresso, listening to music, talking to myself while editing my manuscript, and feeling the kick of caffeine. All the while, stories are weaving in and out of my mind effortlessly. Our stories exist on a broad spectrum, from the harmful (I will never pass this trigonometry test) to the helpful (I’m ready to ace that master’s degree), from the prosaic (Today is the day I clean up my inbox) to the profound (If I keep the faith and take care of myself, I’ll get through this diagnosis).

This chapter reveals how our stories and thinking emerge from an unconscious collaboration between nature and nurture. We explore how the brain is the primary driver of our perceptions and egos and our autopilot thinking and reacting.

The brain takes in something like 40 million bits of data per second. The average human brain contains 100 billion neurons, which form an incomprehensibly complex network with a ton of storage capacity, swirling with constant activity. Our brains manage a barrage of visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory signals with blinding speed. And like magic, they filter the incoming data, connect dots, produce perceptions, make predictions, and help us make sense of the world. Our brains are also story-making machines, relentlessly monitoring what’s happening in the moment, correlating it with our lives’ experiences, and predicting what might happen next. They birth our stories. As story-making machines, they work around the clock, effortlessly, which is fundamental to our survival.

Neuroscience, an exciting frontier in brain research, is just beginning to map these complex cerebral circuitries. I can’t do the research justice, but understanding the neuroscientific basics will help us understand conscious conversations. Our brains consist of the neocortex, entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, left hemisphere, right hemisphere, the corpus callosum, and more. This incredible network supports biological switches, neurons, synapses, axons, and dendrites, which generate an intricate dance of electrical sparks that become our felt experience. A lot is going on under the hood, without conscious effort.

When the brain is doing its job, the person we become emerges from the collaboration between nature and nurture. Our DNA and all our inborn physical qualities constitute our nature. The whole of our life experiences plays a role in defining who we are, what we think, and how we feel and act (and react). Our native country, parents, education, society, and culture all constitute the nurtured self. From birth, we learn to survive by adopting concepts and developing patterns of thinking and emotions from our cultural milieu. Our DNA and social norms are inseparable, and this combination is at the root of our thinking, prejudices, judgments, emotions, and stories.

Depending on how the network is lighting up, we can experience memories of our first love, jealousy over a friend’s success, anger at our overpowering boss, or pleasure from a piece of chocolate. Scientists, psychologists, and neuroscientists are still discovering the mysteries of this remarkable collaboration. Neuroscience is still in its infancy, but it’s clear that there is much it can teach us about what makes us tick and why we do what we do.

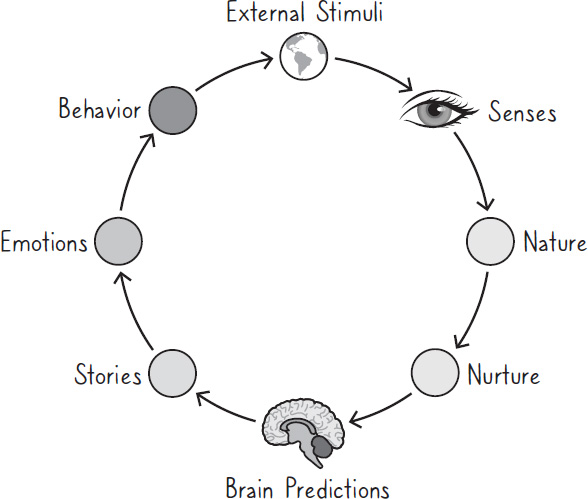

Figure 1 is a broad view and simplification of the complexity of our minds and patterns. It’s a picture to help us appreciate the origin and nature of our stories. External stimuli permeate our senses (vision, audition, olfaction, taste, and touch). Then the brain’s complex systems—synthesizing nature and nurture—interpret and filter the incoming signals, make predictions, and form our perceptions. We then feel, think, and act on our background assumptions, prejudices, and filtered perceptions. The process is circular. Our brain, body, and mind are inextricably linked, and they create narratives from the sounds, sights, temperatures, smells, tastes, and experiences we encounter. How we show up at any given moment is based on all we have felt, thought, and done before. All conscious and unconscious predictions and explanations are filtered through our past and woven into the present moment. Stated simply, we’re explanation-oiled, judgment-filled, assumption-making machines.

FIGURE 1: Our brain and stories

This all works beautifully, but when a situation presents any significant deviation from our daily routine or when someone rubs up against an embedded story, our tried-and-true patterns of thought and behavior are interrupted, and we often react on autopilot. The stress of a flat tire, a demanding boss, a child in distress, a loss of money, or an unexpected medical diagnosis can cause us to react with fear, tears, anger, resentment, or disbelief. These are reasonable and normal reactions, but when we unconsciously get lost in the drama of the moment, we can easily find ourselves overwhelmed, stressed by emotion. Unexamined, our stories and reactionary patterns trap us in nonproductive loops, and we become victims of an unreasonable boss, an unfaithful partner, or a ranting neighbor. Then our conversations suffer.

Awareness

The ultimate value of life depends upon

awareness and the power of contemplation

rather than upon mere survival.

—ARISTOTLE

Without our miraculous unconscious brain activity, we would drown in data overload. While we go about our day-to-day activities, our mind manages our physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing. We generally operate as a bundle of habits and well-worn neural networks we didn’t even choose.

Neuroscience confirms our capacity to operate at different levels of awareness. Awareness is the antidote to our conditioned habits. By cultivating awareness, we become mindful of our mind, including thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations. We can think about our thinking, which is often called our witnessing self.

For a moment, close your eyes and simply pay attention to the thoughts and feelings arriving in your mind. No need to do anything other than observe. Notice what’s arising—your breathing, your thoughts, your feelings, external sounds, and your bodily sensations. This simple exercise can give us a taste of mindfulness. We’re conditioned to distraction, but when we pay attention, we discover that we often think without awareness that we are thinking. Whether through meditation or other methods (see Chapter 3, “Opinions and Private Conversations”), we can be conscious observers of our minds.

I have been meditating since I was eighteen years old. Through meditation, I learned to be a neutral observer of my thoughts, body, and feelings. Over time, my practice helped me become aware of the habits of my mind. Thoughts, sensations, and sounds came and went with no effort on my part. When I observe worrisome or negative thoughts or judgments, a space is created between me (the observer) and the thoughts. Over time, the distractions of the mind’s comings and goings produce a detachment from them, and we can experience a separate conscious self. I have always liked the metaphor of consciousness as the clear blue sky and our streaming thoughts as clouds coming and going. Like the blue sky, our consciousness is always present. But as the skies cloud over, so too are our awareness and consciousness clouded over by our thoughts. Meditation is a practice that allows us to experience an always present clear consciousness.

If you’re interested in trying meditation, there’s a simple practice at the end of this chapter. No beliefs, special equipment, or gurus are required. It’s just you, your mind, and a little time. Apps like Sam Harris’s Waking Up, Dan Harris’s Ten Percent Happier, and Calm are also useful.

Any work we do to increase awareness of our internal patterns directly affects our interactions with others. With my increased understanding of conversations, I have become more aware of myself in conversation and more perceptive of others. But I’m far from perfect, and there are days when my worries and reactions get the best of me (I have a particular aversion to service incompetence, to name one).

Changing unproductive patterns takes time. If I snap at a person helping me with a technical or financial problem, I might not become aware of my failing until hours later. The key to changing that pattern is noticing and noting its harmful effects. Instead of brushing off the frustration or blaming others, if we recognize their harm, we can investigate the pattern (more on this process in Chapter 3) and practice undoing it. With attention and some luck, on my next call with a service person, I might notice my trigger within two minutes or even two seconds and wake up in time to change the negativity of the conversation into one of mutual respect. Then I’m far likelier to get the service I need.

With increased awareness, our habitual background thoughts and judgments become less domineering, and we can catch ourselves in time to shift our reaction and a conversation. Minimizing judgment of our patterns helps us find humor in them so we can enjoy a good laugh. Humor is a great stress reliever and can lighten up most conversations.

I grew up with a racist step-grandfather. His unexamined assumptions, judgments, and prejudices seeped into my unconscious. My brain took in his stories about people of color hook, line, and sinker. As a child, I didn’t consciously choose to adopt his judgments, but in the context of my family, my grandfather’s words had authority, and his beliefs infused into mine. When I became aware of these harmful, racist stories, I was surprised at how ingrained they were. It took time and conscious effort to recognize and acknowledge this pattern and change my thinking, but I can still hear distant whispers of his words in my mind. I know that they aren’t true, and I’m thankful that I’m free of them.

It takes courage to inquire into our thoughts and beliefs. My inquiries were an eye-opener. Questions arose: Why did I feel insecure around certain people? Why did my mouth go dry when I was challenged? Why did I cry at one event and feel untouched by another? Why was I thinking one thing and saying something else? Is it possible that what I believed was simply one way of seeing, looking, and feeling?

Increasing our awareness of our thoughts while we are engaged in conversation with ourselves and others is an important first step toward having conscious conversations.

Autopilot

Unconscious processes of the brain hide useless information from us while bringing data vital for survival to the surface. The autopilot brain is a significant determinant of how we experience and navigate the world. Many of our stories run on autopilot. They quickly move us into action to avoid an oncoming tiger or truck. And they save us energy so we don’t need to stop and ask, How should I make my morning coffee? What’s the best route to the office? How do I save a file? But they also have drawbacks.

Our brains work so quickly that we simply don’t question our background stories. When we’re mindless, we engage in conversations loaded with private thoughts, judgments, emotions, and egos—I’m so done with this idiot! Why on earth can’t people be on time? How is it that people can believe that political B.S.?

As I write these words, the United States is in unprecedented political turmoil. This political climate is a perfect example of how difficult it is to be mindful and wake up out of autopilot. Facts are in doubt, the press is polarized, and constructive conversations are rare. The general public and politicians are all crying foul. My clients and friends on both sides of the aisle email and text me in disbelief. “How can they want to teach that in our schools?” “How on earth can they believe those idiots in Congress?” “The Supreme Court is nothing but another political arm. Maybe it’s time to expand the bench.”

Like it or not, as life unfolds, it often isn’t aligned with our story of what should be happening. The difference between what we want to happen and the reality of what’s happening is a source of suffering. When we don’t like what we see, the battle between our stories and reality—small (the weather) and large (relationships)—plays out in our minds, feelings, and conversations. “Bosses shouldn’t act that way.” “Men shouldn’t treat women that way.” “She shouldn’t spend so much on shoes.” “Governments can’t manage anything.”

○ ○

A talented client, Paul, was desperate to become a director in his company. He had a good story going in his head: The next director position belongs to me. In his mind, his colleagues were incompetent, but he had worked hard and earned the position. His ego was whispering that this imminent next step up the corporate ladder was his ticket to more money and greater prestige—a gratifying story. He wanted and needed that job.

Here’s the rub: Paul’s unchecked story had him stressed out. Anxious, impatient, and obsessed, he began to second-guess himself: Should I speak up? Are they listening to my opinions? What do I need to do to get them to recognize how good I am? He questioned what he said, how he dressed, and what others thought of him. His anxious behavior led to an outcome opposite of his goal. Rather than being present and confidently speaking his opinions and sharing his ideas, he showed up as insecure and nervous.

When the announcement came that he wasn’t promoted to director, he was crushed. Reality didn’t match his story about what should have happened. He told himself that the company’s decision was wrong-headed, unjust, and unhinged. He suffered because his blinding story kept him from understanding why others weren’t perceiving him as the perfect candidate. He was depressed for weeks.

Coincidentally, we were introduced to one another and started to work together. First, I asked Paul to do some journaling. He wrote down his story with his judgments and assumptions unedited. His words on paper revealed a big gap between his need to land that job and the reality on the ground. While doing this work, he came to see the negative impact of his neediness and insecurities. Armed with new observations, he recognized that his unchecked story was his own worst enemy.

Paul’s anxiety lessened as he adopted new practices and reframed his story. He slowly gained more confidence and found his voice in meetings. He closed the gap between his blind desires and the reality of his situation. Paul had new insights and began to try on new ways of showing up. Over time, he got his promotion, and he was a better leader for the work that he did on himself.

○ ○

We function well with our background stories running on autopilot— until we don’t. We can cruise along like Paul, stressed out and sticking with our stories of what should be happening. We can do that for minutes, days, years, or decades—until we run smack-dab into a person or an event that slams us back into reality.

When we pay attention to our habitual reactionary patterns, we will inevitably encounter our ego.

The Ego

It seems to me that most of us are not aware, not only of

what we are talking about but of our environment, the

colors around us, the people, the shape of the trees, the

clouds, the movement of water. Perhaps it is because we

are so concerned with ourselves, with our own petty little

problems, our own ideas, our own pleasures, pursuits and

ambitions that we are not objectively aware.

—J. KRISHNAMURTI, thinker and spiritual teacher

As we observe ourselves in conversation, we come face to face with the ego. Don’t be such an idiot. They’re so wrong. Who are they to talk down to me? One job of our ego is to identify with every element (i.e., judgments, prejudices, and beliefs) of our stories and to defend them at all costs, even in the face of inconvenient facts. When you listen to your mind’s background commentary, you will hear your ego yapping away. While you’re frowning and agreeing with one neighbor about another barking dog, your ego is whispering, I can’t believe this guy is such a jackass!

The ego would be pleased if we never questioned our stories and peeked at the mind’s underbelly. It prefers that we stay on autopilot and not rock the boat. So when you ask questions like, Why am I reacting this way?—the answer in your head might sound like this: Because I’m right and they’re wrong! Or maybe this: Why am I feeling so insecure? Because I’m an idiot, I’d better keep my mouth shut. These answers are the ego’s way of clinging to a story while suppressing our curiosity and awareness. The ego wastes no time in its defense. It’s tricky, quick, addictive, and convincing.

The shape-shifting ego can be our victor, victim, critic, or denier. It will assume any form necessary to defend its assumptions and subsequent narratives. As we begin to witness and increase awareness of our stories, the ego will reveal itself in all its defensive glory. It’s adept at assuring us that our stories should remain intact and unquestioned. As I began to observe and question the prejudices and judgments in my stories, I slowly realized that my ego was always ready with an explanation: Of course, they’re wrong. How can they be so stupid? Or, Don’t be so hesitant. Get out there and defend yourself. My arrogant and belittling ego was a deafening critic.

With the ego running the show, we can, at any moment, see ourselves as brilliant or idiotic. At a party, we might glance around the room and find ourselves thinking, These people are dimwitted. On the other hand, we could be driving to a family get-together, stomach tightening, thinking, I’m such a failure. How am I going to face them? I was drunk when I visited last. Negative judgment of others and self-judgment is the ego’s specialty.

The ego identifies with our stories and ensures that our environs, actions, and reactions are all about me, me, and me. It’s always sure that it knows how events should unfold and what we should do. Paramount to the ego is our belief that our story is the “truth.” It leaves little room for doubt, questions, or curiosity. When the ego is in charge, we have to be right.

Investigating our stories starts a process of disengaging from the ego. A crucial part of awareness is paying attention to our autopilot egoic thinking with nonjudgmental curiosity. Judging our judge only sends us on an endless loop of negativity. By acknowledging the ego with empathic curiosity, we can begin to tame it.

○ ○

I have a thing about being on time. I wasn’t aware of this habit until my second marriage to a lovely woman who has a different relationship with time. I can be ready to go and get out of the house a lot faster than my wife can. Years ago, as I was sitting in the car, ready to go, I found myself impatiently stewing. What on earth could be taking her so long? I got all twisted up, and I built up a good head of steam to unload on her . . . or on the gas pedal. It seemed pretty clear-cut to me. I was right because I was always on time, and she was wrong because she was always late. After filling the car with my unspoken, angry judgments, we drove to our destination in stressed silence.

I was in lockdown and blinded by my ego’s attachment to the “right way,” which carried my beliefs about time, preparation, and lateness. I was clueless about how much more time she needed to get ready than I did. I showered, towel-dried my hair, threw on some jeans and a semi-clean shirt, slipped on my shoes, grabbed my keys, and headed for the door. What could be simpler? My ego was full of righteous indignation. When that happened, we both stressed out, which made for a pretty crappy start to a night out.

This relationship aha happened while I was studying the ontology of language with the Newfield Group. Here was a chance to put theoretical ideas into practice. I practiced catching my emotions and the accompanying self-righteous story and ego in action. Curiously observing my auto-emotional reactions helped me unhook from them, and I was able to take a good hard look at my uninvestigated judgments.

Believe it or not, it took this breakdown for me to become aware of my wife’s needs, timing, and patterns. I came to accept how much she relishes her shower and bathroom spa time, enjoying the time to care for her body, her hair, her face, her clothing, and her jewelry. Her comfortable patterns and way of preparing for a night out could not be more different from mine.

I discovered that my story wasn’t the truth by working with this mundane, everyday dilemma. It was loaded with a bucketful of judgments, prejudices, and assumptions. When I was able to witness and catch my triggers in real time, I could stop stewing and arguing.

As I woke up from autopilot reactions, we were able to talk about our patterns. We learned to appreciate our differences and talked about them without the stress. We agreed on some ways to change our rituals and test them out. We both shared a desire to be on time to events. I took responsibility for my impatience, and she agreed that she could be more aware of her routine and the time she needed to get out the door.

It seems obvious now, but it took a little planning and conscious effort to alter our pattern. My wife needed to stop whatever she was doing one hour before we needed to leave, and I could play a game of solitaire on my phone, practice the piano, or even ask if there was a way to help her rather than stewing. Our new agreement was critical for changing the dance. Eventually, we were more relaxed when getting ready to go out. In this simple but powerful experience, I checked my ego, and through our conversations, we eliminated a bunch of frustrations.

○ ○

Our everyday interactions at work and home provide us with plenty of material to work with. In the remaining chapters, we’ll dissect the heart of our sense-making stories and experiment with new tools for working with them.

PRACTICES

○ Begin to note your triggers (e.g., the kids, your boss, your in-laws, loud music, a neighbor’s dog, traffic). Is there a pattern of impatience, frustration, insecurities?

○ Rather than berating your ego, try befriending it by simply observing its message. This is a powerful way to witness rather than to blindly accept the thoughts.

○ Practice being mindful at home and at work and observe what’s happening in the moment to see what thought patterns seem to repeat themselves. How do you feel different when you take a moment to be mindful?

○ Simply note your recurring automatic reactions and emotions on any given day. Be mindful of your judgments and the emotions that accompany them.

○ How do you feel differently when you’re simply observing yourself or others with curiosity rather than with judgment?

Here’s a meditation practice based on Vipassana, a well-regarded, well-researched method:

1. Find a comfortable sitting position, your spine straight.

2. Take a few breaths to settle into your seat.

3. Close your eyes and continue taking a few breaths. Notice your body sitting in the chair. Notice any bodily sensations that arise—warmth, tense muscles, a grumbling tummy.

4. Gradually bring your attention to your breath. Pick the spot where you most feel your breath—your nose, tummy, chest.

5. Allow your attention to rest there, noticing your breath coming in and out, naturally.

6. As you pay attention to your breath, you will simultaneously begin to notice thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations. Observe them as they arise.

7. When you notice you have been distracted by thoughts, sounds, or feelings (this is your mind running its pattern, which is totally normal), gently return your attention to your breath.

8. Continue keeping your breath at the center of your attention, noting all thoughts, sounds, and sensation as objects of consciousness, arising and passing through.