Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Complete Project Manager's Toolkit

Randall Englund (Author) | Alfonso Bucero (Author)

Publication date: 04/01/2012

Buy both The Complete Project Manager and The Complete Project Manager's Toolkit and save $18 at checkout by entering coupon code COMBO1.

This companion to The Complete Project Manager provides the tools you need to integrate key people, organizational, and technical skills. The core book establishes that success in any environment depends largely upon completing successful projects; this book gives you the means and methods to meet that goal. The hands-on, action-oriented tools in this book will help you develop a complete set of skills—the right set for you to excel in today's competitive environment.

The Complete Project Manager's Toolkit will enable you to implement the easy-to-understand, universal, powerful, and immediately applicable concepts presented in The Complete Project Manager. You may already be aware of what you need to do; this book supplies the how through:

• Assessments

• Checklists

• Exercises

• Examples of real people applying the concepts.

Use these tested methods to overcome environmental, personal, social, organizational, and business barriers to successful project management!

Although The Complete Project Manager can be used as a stand-alone book, it is designed to complement The Complete Project Manager: Integrating People, Organizational, and Technical Skills.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Buy both The Complete Project Manager and The Complete Project Manager's Toolkit and save $18 at checkout by entering coupon code COMBO1.

This companion to The Complete Project Manager provides the tools you need to integrate key people, organizational, and technical skills. The core book establishes that success in any environment depends largely upon completing successful projects; this book gives you the means and methods to meet that goal. The hands-on, action-oriented tools in this book will help you develop a complete set of skills—the right set for you to excel in today's competitive environment.

The Complete Project Manager's Toolkit will enable you to implement the easy-to-understand, universal, powerful, and immediately applicable concepts presented in The Complete Project Manager. You may already be aware of what you need to do; this book supplies the how through:

• Assessments

• Checklists

• Exercises

• Examples of real people applying the concepts.

Use these tested methods to overcome environmental, personal, social, organizational, and business barriers to successful project management!

Although The Complete Project Manager can be used as a stand-alone book, it is designed to complement The Complete Project Manager: Integrating People, Organizational, and Technical Skills.

Chapter

![]()

1

LEADERSHIP AND

MANAGEMENT SKILLS

TOOLSET: LEADING YOURSELF CHECKLIST

Nothing will make a better impression on your leader than your ability to manage yourself. If your leader must continually expend energy managing you, then you will be perceived as someone who drains time and energy. If you manage yourself well, however, your boss will see you as someone who maximizes opportunities and leverages personal strengths. That will make you someone your leader turns to when the heat is on.

Table 1-1 suggests ways to lead yourself well.

TABLE 1-1: Leading Yourself

| What to Do | How to Do It |

Manage your emotions |

It is especially critical to control your emotions because whatever you do affects many other people. Good leaders know when to display emotions and when to delay expressing them. The bottom line in managing your emotions is that you should put others first—not yourself. Ask yourself, what does the team need? What also makes me feel better? |

Manage your time |

Time management issues are especially tough for people in the middle. Time is valuable. Until you value yourself, you won’t value your time. Until you value your time, you will not do anything valuable with it. Instead of thinking about what you do and what you buy in terms of money, instead think about them in terms of time. |

|

Get yourself to the point where you can manage your priorities and focus your time in this way: • 80% of the time, work where you are strongest. • 15% of the time, work where you are learning. • 5% of the time, work in other necessary areas. If you have people working for you, delegate to them tasks you are not good at but they are. The secret to making this shift is often discipline. Be ruthless in your judgment of what you should not do. Just because you like doing something does not mean it should stay on your to-do list. If a task is related to one of your strengths, do it. If it helps you grow, do it. If your leader says you must handle it personally, do it. Anything else is a candidate for your “stop doing” list. |

|

Manage your energy |

Some people have to ration their energy so that they don’t run out. Always make sure you have the energy to do tasks with focus and excellence. Even people with high energy can have that energy sucked right out of them under difficult circumstances. Leaders, especially those in the middle of an organization, often have to deal with the “ABC energy drain”: • Activity without direction: doing things that don’t seem to matter • Burden without action: not being able to do things that really matter • Conflict without resolution: not being able to deal with what’s the matter If you find that you are in an organization where you often must deal with these ABCs, then you will have to work extra hard to manage your energy well. |

Manage your thinking |

The greatest enemy of good thinking is busyness. And leaders in the middle are usually the busiest people in an organization. If you find that the pace of life is too demanding for you to stop and think during your workday, then get into the habit of jotting down three or four things that need good mental processing or planning that you cannot stop to think about. Then carve out some time later when you can give those items some good think-time. That may be 30 minutes at home the same day, or you may want to keep a running list for a whole week and then take a couple of hours on Saturday. Just don’t let the list get so long that it disheartens or intimidates you. |

TOOLSET: DELEGATING EFFECTIVELY

Don’t take on tasks that someone else can do as well—or better—than you. Although a project manager cannot delegate everything in a project, delegating can make a project manager’s life easier. But many are hesitant to pass on responsibilities.

Don’t think of delegating as doing the other person a favor. Delegating some of your authority only makes your work easier. You will have more time to manage your project, monitor team members, and handle conflicts. Your organization will benefit, too, as output goes up and project work is completed more efficiently.

Communication is the key to delegating. Without communication, assignments are blurred, deadlines are vague, and results are, predictably, poor. If you want your team to excel as they take on added duties, talk to them, recognize them, and reward them.

To delegate effectively, follow these steps:

| What To Do | How To Do It |

| Outline the purpose and importance of the project | Don’t expect your team members to ask enough questions to define the project. Be sure to explain the work clearly and thoroughly. |

| Provide the necessary authority | Make sure the team member you have chosen has the clout needed to complete the task. Otherwise, requests to others for help and information may be ignored because they don’t come from you. |

| Delegate for results | Set standards and make sure team members know they will be held accountable. When a problem arises, use it as a chance to show a staffer how to handle it. |

| Review and follow | Setting deadlines and enforcing them will establish team members’ commitment to getting the work done. |

To make sure you are delegating to the right person, consider these factors:

Friction: Disagreement between you and the person taking the assignment is healthy while the assignment is being made. It is only a problem if it extends into the execution stage.

Track record: Match the job to the person. Past performance is significant only as it relates to the job you’re delegating.

Location: Don’t delegate just because someone is close by or is not busy and is convenient to ask.

Organization level: If you want to delegate a job to someone several levels down in the organization, first confer with his or her supervisors and explain the situation.

Compatibility: Ideally, your work and communication styles and that of the person to whom you are delegating the work should be complementary.

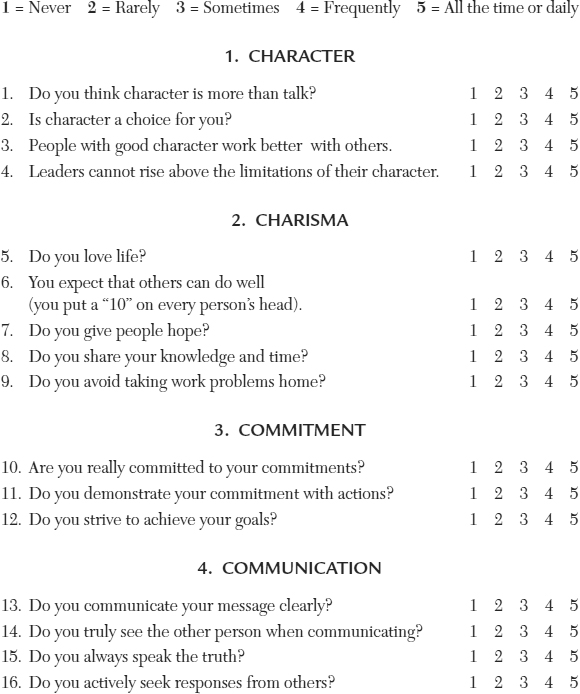

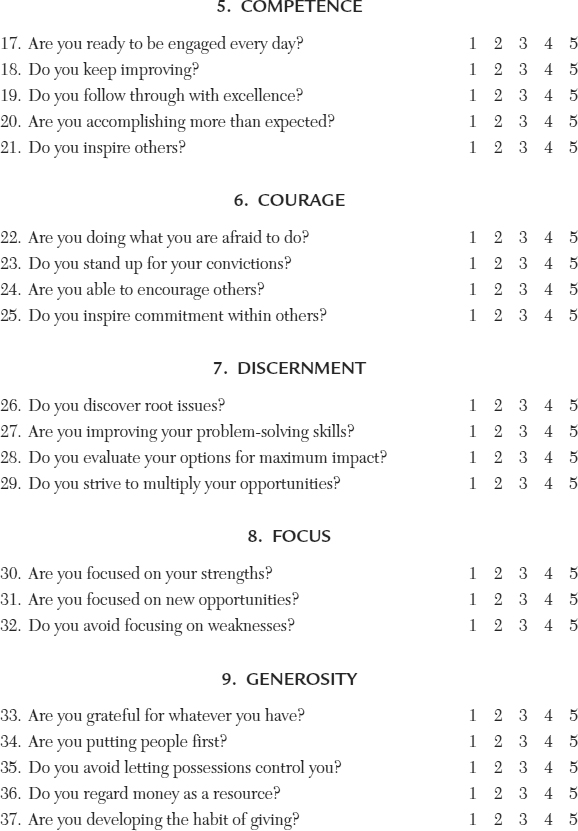

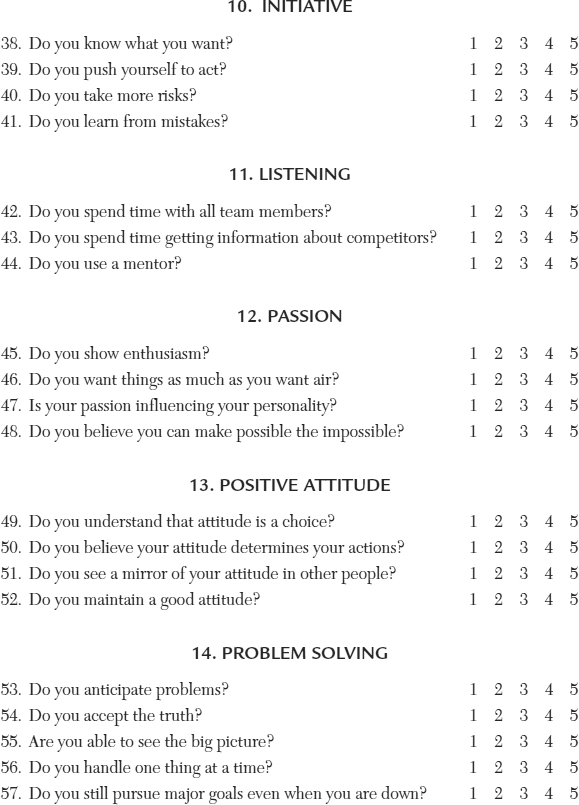

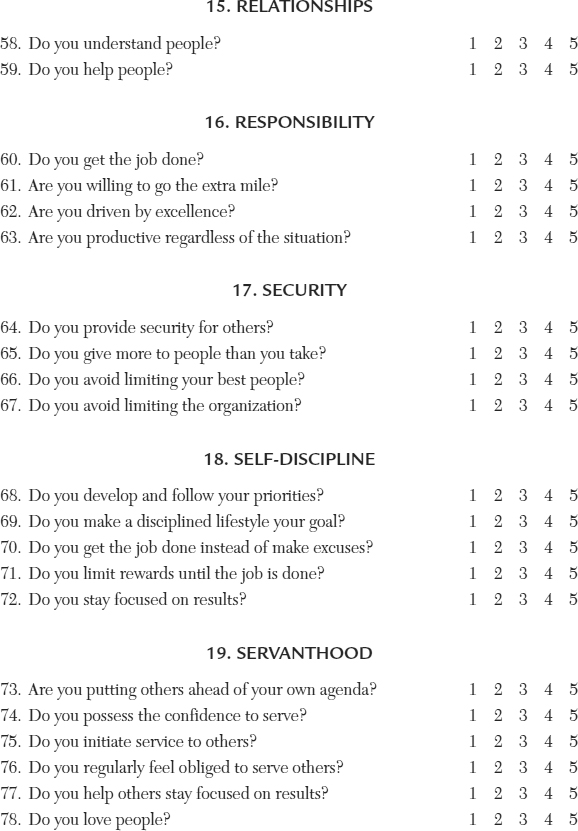

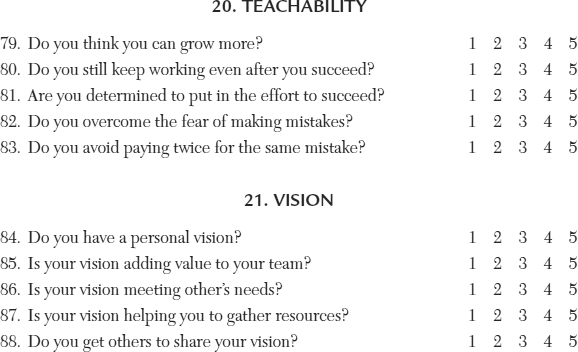

TOOLSET: 21ST-CENTURY LEADER QUALITIES ASSESSMENT

This tool helps you to assess your qualities as a leader. There are 21 characteristics to be assessed. Carefully select the number on the right that represents your present situation.

The codes to use are as follows:

How to calculate your score:

First, count the number of 1s that you circled and write that number next to 1x under CALCULATIONS. Do the same for all of the 2s, 3s, 4s, and 5s you circled.

Multiply the number you wrote down in each of the blanks by the number to the left (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5). Write each of these subtotals in the blanks to the right of the equals sign, then add them to get your total score.

CALCULATIONS

TOTAL SCORE____

| Scoring | Meaning |

| 0-88 | Make a concerted effort to address all leadership characteristics. Study hard. Seek a mentor. Pay attention to how others address similar issues. If all seems hopeless, try something else. |

| 89-176 | You need focused work. Ask for feedback from others. Attend leadership training. |

| 177-264 | Your leadership skills are average, and there is room for improvement. Find ways to develop unique skills that enable you to stand out. Achieve small successes; learn from those successes and apply lessons learned to achieve greater successes. |

| 265-352 | You are almost there. Keep improving. Help others. Maintain a positive attitude. |

| 353-440 | Congratulations—you are almost complete. Be a mentor. Share your wisdom. Serve as an example for others to emulate. |

The following toolset offers suggestions to help you improve your leadership skills in these 21 dimensions.

TOOLSET: CHECKLIST OF QUALITIES FOR 21ST CENTURY LEADERS

To be an effective leader, practice and develop all the following qualities and skills.

| What To Do | How To Do It |

Character |

|

Charisma |

|

Commitment |

|

Communication |

|

|

|

|

Courage |

|

Discernment |

|

Focus |

|

Generosity |

|

Initiative |

|

Listening |

|

|

|

|

Positive attitude |

|

Problem-solving |

– Time: spend time to discover the real issue – Exposure: find out what others have done – Assistance: have your team study all angles – Creativity: brainstorm multiple solutions – Hit it: implement the best solution.

|

Relationships |

|

Responsibility |

|

Security |

|

Self-discipline |

|

|

|

|

Teachability |

|

Vision |

|

TOOLSET: ATTITUDE IS EVERYTHING

Human beings are like sponges: we soak up whatever those around us are saying. Unfortunately, we can’t always distinguish between messages that are good for us and those that aren’t. If you hear something often enough, you tend to believe it and act on it.

That’s why negative colleagues can be so harmful. They try to drag you down to their level. They hammer away at you by harping on all the things that you supposedly can’t do, things they say are impossible. These people can be called “dream killers” or “energy vampires,” because they suck all the positive energy out of you. Eventually, you get frustrated and lose motivation.

Compare that with how you feel when you’re around team members who are enthusiastic and supportive. You pick up their attitude and you feel as if you have gained more strength to vigorously pursue your own goals. You’re energized and inspired—and you perform better.

The people who occupy your time have a significant impact on your most priceless possession: your mind. Now and then, it is important to assess your relationships with colleagues—even those you’ve worked with for many years. Are you surrounding yourself with negative people? If so, consider spending much less time (or no time at all) with them.

Of course, you can’t always choose who you work with. Many times you have to cope with negative colleagues; you may not have the option to avoid them. In those cases, follow these practices:

Discover the roots of their negativity. Perhaps they don’t feel appreciated or they didn’t feel supported on earlier projects. Understanding is the first step.

Remind them every day that they have a choice. They may not be able to change the project or organizational situations, but they can choose to be happy (or unhappy).

Ask them to make an effort to be more positive. That includes curbing their use of words such as failure and impossible.

Show them you care. Speak to all team members for at least a few minutes every day, and they will soon understand that you care about them. Concerned, loving, respectful leaders can move mountains.

Such actions can help get at the root cause of your colleagues’ negativity and begin to turn them into positive people. As you increase your associations with positive people, you will feel better about yourself and will have renewed force to achieve your goals. You will become a more upbeat person—the kind of person others love to be around— and your work will reflect that.

We used to think it was merely helpful to associate with positive people and to limit involvement with negative people. Now we believe it is absolutely essential. Surround yourself with positive people, and they will lift you up the ladder of success.

TOOLSET: PROJECT MANAGER TEACHABILITY

Here are guidelines to help cultivate and maintain a teachable attitude:

Cure your “destination disease.” Lack of teachability is often rooted in achievement. Some project managers mistakenly believe that if they can accomplish a particular goal, they no longer have to grow. Complete project managers cannot afford to think that way. The day they stop growing is the day they forfeit their potential and the potential of the organization.

Overcome your success. Effective project leaders know that what got them to a particular level does not keep them there. If you have been a successful project manager in the past, beware. Consider this: if what you did yesterday still looks big to you, you have not done much today.

Swear off shortcuts. If you want to grow as a project manager in a particular area, figure out what it will really take, including the price, and then determine to pay it.

Trade in your pride. Teachability requires us to admit we do not know everything, and that can make us look bad. One of the greatest mistakes one can make as a project manager is to continually fear you will make one.

Never pay twice for the same mistake. Whoever makes no mistakes makes no progress. But the leader who keeps making the same mistakes also makes no progress. For every mistake you make, focus on what it taught you.

In order to improve your teachability, do the following:

Observe how you react to your mistakes. Do you admit your mistakes? Do you apologize when appropriate, or are you defensive? Observe yourself. You are a project leader, and your team expects you to lead by example. If you react badly or you make no mistakes at all, you need to work on your teachability.

Try something new. Get out of your project rut today and do something different that will stretch you mentally, emotionally, or physically. Challenges change us for the better. If you really want to start growing, make new challenges part of everyday activities.

Learn in your area of strength. Read 6 to 12 books a year on leadership or on project management. Continuing to learn in an area where you are already an expert prevents you from becoming jaded and unteachable. Becoming an expert (in anything) requires 10,000 hours of study, according to leadership authors Kouzes and Posner (2007).

TOOLSET: LISTENING TO PEOPLE

We have observed these listening behaviors:

Hearing: The listener hears your comments but does not process anything in his brain. He then forgets the message.

Information gathering: She is just collecting information, not really listening to anything other than the specific information she is seeking.

Cynical listening: He seems to be listening to you and is nodding along as you speak—but these are deceptive behaviors because he is thinking about something else, not actually listening.

Offensive listening: She is not focused on you as you talk. She does not look at you or is doing other things while listening—perhaps working on a computer or answering a call.

Polite listening: His listening manners are good—he is quiet and looks at you as you speak—but how much is he really absorbing?

Active listening: She paraphrases and validates what she understood about your talk.

Listening is hard work. Unlike hearing, listening demands total concentration. Listening is an active search for meaning, while hearing is passive. Try to listen with these questions in mind:

What is the speaker saying?

What does it mean?

How does it relate to what was said before?

What point is the speaker trying to make?

How can I use the information the speaker is giving me?

Does it make sense?

Am I getting the whole story?

Is the speaker supporting his or her points?

How does this relate to what I already know?

Also ask questions, especially clarifying questions. Words have definitions, but meaning comes from the person who is speaking. To understand the full meaning, you may have to help the speaker by following up with questions. Maintaining eye contact and nodding occasionally, when appropriate, also help to let the speaker know you are listening.

Paraphrase when you want to make sure you have understood, when you are not sure you have caught the meaning, and before you agree or disagree. Paraphrasing is also useful when dealing with people who repeat themselves—it assures them they have communicated their ideas to you.

Be cognizant of three levels in cross-cultural exchanges:

Pay attention to the person, his culture, his background, and the message.

Create rapport by finding some values in common.

Share meaning. Verbalize stereotypes and work through them to check that your understanding and the other person’s are correct.

Listen better to project stakeholders, and you will learn more about your project.

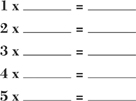

TOOLSET: HOW ARE YOU LISTENING?

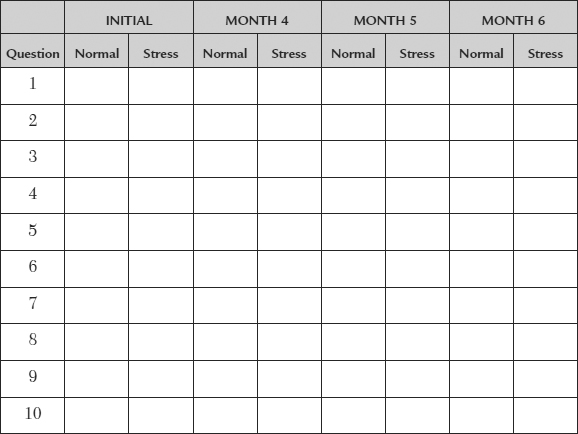

Every 30 days, score yourself on a scale from 1 to 10 (10 = maximum) in the following areas. Convert your score to a percentage (100 = 100%). Then record your results on the next pages to monitor your progress.

| Questions | In a normal situation | Under stress |

1. How much attention do you pay to the words the other person is saying to you when you are listening to him/her? |

||

2. How much attention do you pay to the tone of voice of the person who is talking to you? |

||

3. Do you wait to talk until the other person finishes? |

||

4. Do you maintain visual contact while talking? |

||

5. How well do you understand the other person’s body language? |

||

6. When the other person is talking, do you listen fully, not partially? Do you focus on him/her rather than thinking about what you will say when he/she finishes talking? |

||

7. Do you always paraphrase the other person’s words? |

||

8. Do you try to put yourself in the shoes of the speaker when listening? |

||

9. Do you apply different listening filters depending on the culture or gender of the speaker, such as how they view time, relationships, or conversations? |

||

10. Do you demonstrate interest in the other person when listening? |

||

| Scoring | % | % |

90-100%: Phenomenal

80-90%: Very good

70-80%: Good

60-70%: Medium

50-60%: You need to improve

40-50%: You need to improve a lot

SCORING RECORDS

TOOLSET: LISTENING IMPROVEMENT TOOL

For all the following skills, please write specific actions that you can take in order to improve. Pay particular attention to those areas in which your scores were lower.

| Key areas for improvement | What will I do to improve? |

| Being present and communicating my interest in what the other person is saying | |

| Waiting until the other person finishes before starting to talk | |

| Listening completely and patiently before planning a response | |

| Listening to specific words versus global meaning | |

| Tone of voice/inflection | |

| Reading body language | |

| Repeating what I heard to confirm my understanding with the sender | |

| Empathy: being in the speaker’s shoes | |

| Understanding how cultural, gender, and local differences affect communication | |

| Looking at the eyes of the other person when he or she is talking | |

| Using body language such as gestures to listen better |

TOOLSET: DEVELOPING RELATIONSHIPS UP THE ORGANIZATION

Here are some practices that we find extremely helpful in running projects within organizations:

Listen to your leader’s heartbeat.

Try to understand what makes him or her tick. That may mean paying attention in informal settings, such as during hallway conversations, at lunch, or in the meeting that often occurs informally before or after a meeting. If you know your leader well and feel the relationship is solid, you may be more direct and ask questions about what really matters to him or her on an emotional level.

If you are not sure what to look for, focus on these three areas: What makes him laugh? This is very important. What makes him cry? This is what touches a person’s heart at a deep emotional level. What makes him sing? These are the things that bring deep fulfillment.

All people have dreams, issues, or causes with which they connect deeply. Those things are like the keys to their lives. Are you aware of the things that touch you on a deep emotional level? What are the signs that they “connect” for you? Do you see those signs in your leader? Look for them, and you will likely find them.

Know your leader’s priorities.

Leaders’ priorities are the things they have to do. But priorities are more than just tasks on a to-do list. All leaders have duties that they must complete or they will fail in fulfilling their responsibilities. Priorities are those short-list responsibilities that your leader’s boss would say are do-or-die for that position. Make it your goal to learn what those priorities are. The better acquainted you are with those duties or objectives, the better you will understand and communicate with your leader.

Catch your leader’s enthusiasm.

It is much easier to work with someone when you share enthusiasm. If you can catch your leader’s enthusiasm, it will have a similarly energizing effect on you, it will create a bond between you and your leader, and you will pass it on, because you will not be able to contain it.

Support your leader’s vision.

When top leaders hear others articulate the vision they have cast for the organization, their hearts sing. This feeling is very rewarding. It represents a kind of tipping point, to use the words of author Malcolm Gladwell. It indicates a level of ownership by others in the organization that bodes well for the fulfillment of the vision. Leaders in the middle of the organization who are champions for the vision become elevated in the estimation of a top leader. They get it. They are on board. And they have great value to the organization.

Never underestimate the power of a verbal endorsement of a vision by a person with influence. As a leader in the middle, if you are unsure about the vision of your leader, then talk to that person. Ask questions. Once you think you understand it, quote it back to your leader (when appropriate) to make sure you are in alignment. If you got it right, you will be able to see it in your leader’s face. Then start passing the vision on to the people in your sphere of influence. It will be good for the organization, your people, your leader, and you. Promote your leader’s dreams, and that leader will promote you.

Connect with your leader’s interests.

One of the keys to building relational chemistry is knowing and connecting with your leader’s interests. It is important to know enough about your leader to be able to relate to him as an individual beyond the job. If your boss is a golfer, you may want to take up the game or at least learn some things about it. If he collects rare books or porcelain, then spend some time on the Internet finding out about these hobbies. Just learn enough to relate to your boss and talk intelligently about the subject.

Understand your leader’s personality.

Two staff members were discussing the president of their company, and one of them said, “You know, you cannot help liking the guy.” The other replied, “Yes, if you do not, he fires you.” Leaders are used to having others accommodate their personalities. As you lead down from the middle of the organization, do you not expect others to conform to your personality? We do not mean, of course, that you should fire someone who does not like you. Your expectations should not be unreasonable, nor should you behave in a spiteful way toward people who do not conform to your preferences. But if you are simply being yourself, you expect the people who work for you to work with you. When you are trying to lead up, you are the one who needs to conform to your leader’s personality. It is a rare great leader who conforms down to the people who work for him or her.

It is wise to understand your leader’s style and how your personality styles interact. Most of the time, personality opposites get along well as long as their values and goals are similar. According to the temperament theory of the ancient Greeks, cholerics (doers) work well with phlegmatics (people who are self-content and kind); sanguines (extroverts) and melancholics (ponderers) appreciate each other’s strengths. Trouble can come when people with similar personality types come together. If you find that your personality is similar to your boss’s, then remember that you are the one who has to be flexible. That can be a challenge if yours is not a flexible personality type.

Earn your leader’s trust.

When you take time to invest in relational chemistry with your leader, the eventual result will be trust—in other words, relational currency. When you do things that add to the relationship, you increase the amount of relational change in your pocket. When you do negative things, you spend that change. If you keep dropping the ball, professionally or personally, you harm the relationship, and you may eventually spend all of your relational currency and bankrupt the relationship.

Learn to work with your leader’s weaknesses.

You cannot build a positive relationship with your boss if you secretly disrespect him because of his weaknesses. Since everybody has blind spots and weak areas, why not learn to work with them? Try to focus on the positives and work around the negatives. Doing anything else will only hurt you.

People can usually trace their successes and failures to the relationships in their lives. The same is true when it comes to leadership. The quality of the relationship you have with your leader will impact your success or failure. That investment is most worthwhile.

TOOLSET: GETTING EXTRAORDINARY PERFORMANCE

In a Fast Company article, “How to Lead Now,” John A. Byrne (2003) summarizes ways to get extraordinary performance, especially when you can’t pay for it.

Studies of high-performing organizations show that eliciting great performance comes down to one core issue: building pride.

Getting more productivity out of people comes not by cutting and slashing, but by nurturing, engaging, and recognizing.

Researchers found that spending 10 percent of revenue on capital improvements boosts productivity by 3.9 percent, but a similar investment in developing human capital increases productivity by 8.5 percent—more than twice as much.

“Money attracts and retains people better than it motivates them to excel.”

The push for pride-building comes from individuals within organizations—not from organizations themselves.

Employees are no longer loyal to organizations as much as they are loyal to people.

Pride-building is a task for front-line leaders who are closest to the real work of a corporation.

Commitment and loyalty derive solely from the relationships that leaders develop with the people who report to them.

Personalize the workplace, cultivating close-knit communities inside large, often impersonal corporations.

Pride, happiness, and feeling good come from being part of a winning team.

It is possible to create a group of people who will do anything in the world for a leader.

Create self-reinforcing peer groups of four to seven senior people across the company, connect them via email and phone calls, and have them compete with other teams.

Assign mentoring roles to veterans to assist younger staffers.

Set goals to re-create people’s pride in their work, team, and organization.

Focus on creating engagement that makes a difference.

Remember that work is indeed personal, as it always has been.

Jon R. Katzenbach describes an effective pride-building process in Why Pride Matters More Than Money (2003):

– Personalize the workplace.

– Always have your compass set on pride, not money.

– Localize as much as possible.

– Make your messages simple and direct.

TOOLSET: MANAGING YOUR EXECUTIVES

Michael O’Brochta, PMP, president of Zozer Inc. in Roanoke, Virginia, shared his action steps for influencing executives in a paper, “How to Accelerate Executive Support for Projects” (2011):

Project managers are falling into the trap of applying best-practice project management only to have the project fail because of executive inaction or counteraction. Project managers who continue doing what used to work by focusing within the bounds of the project are now finding success more difficult to achieve. The problem is that project success is dependent, to an increasing degree, not only on the efforts of the project manager but also on the efforts of the executive.

The topic of accelerating executive support for projects falls within the broader context of project success. If we visualize this context as a process, we can focus on examining the actual criteria for project success in the process, and then we can examine the actions we can take as project managers to ensure the project is successful. An expanded definition of success now includes factors well beyond the control or influence of the project manager; executive actions for project success must also be taken to support the efforts of the project manager. This consideration now takes the topic of project success to a whole new level. This new level, which goes well beyond traditional project management, involves great project management and involves focusing outside the traditional bounds of the project, focusing on the executive, and focusing on getting the executive to act for project success.

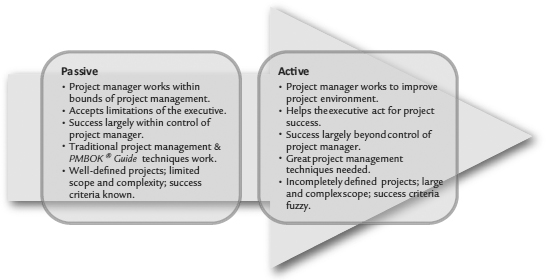

A challenge is to get executives to overcome barriers—such as the demands of their executive responsibilities, the constraints they encounter (both real and imagined), and their limited understanding of the discipline of project management—and actually take action to support projects. At this point, the project manager can adopt a range of attitudes regarding his or her involvement. This attitude range can be characterized as a continuum between passive and active.

At the passive end of the continuum [see Figure 1-1], the project manager remains focused internally on the project, using traditional project management techniques, and pays relatively little attention to changing the workplace environment to enable better project success. Here, we have the project manager accepting the status quo and largely detaching him- or herself from efforts to help the executive overcome the barriers and act for project success.

At the active end of the continuum, the project manager accepts broad responsibility for success of the project and engages in efforts to reshape the workplace environment to support the needs of the project. Here, we have the project manager actively engaged in a codependent relationship with the executive, a relationship in which both parties understand that their success is dependent on each other. Here, we have the project manager expanding his or her focus beyond the traditional project bounds to include helping the executive overcome the barriers and act for project success.

FIGURE 1-1: Shifting Behaviors to Win Greater Executive Support

Executive Support for Projects Model

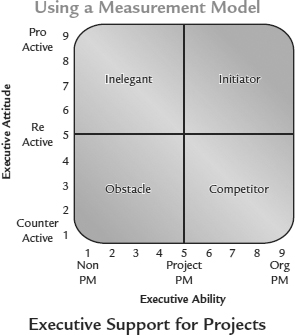

I developed a new two-dimensional model (see Figure 1-2) to gauge the level of executive support for projects. This model includes scales for accessing the attitude of the executive as well as the ability of the executive. I then provide guidance for how to use the model to guide action. The Executive Support for Projects Model is intended as an aid in assessing and diagnosing the organizational environment in which the project manager and executive reside. Armed with a level of understanding about the nature of an executive’s support for projects, the project manager is more likely to find an effective approach to help the executive take the actions for project success. Note that the model represents observable behavior of the executive and can be used to assist in determining the underlying reasons for the behavior.

The Executive Attitude axis is a continuum that represents the attitude of the executive toward taking actions for project success. At the high end of the scale, executives are characterized as proactive—taking initiative to identify and act on opportunities that they see as supportive of project success. The midpoint on the scale pertains to executives who are reactive—those who take supportive action in response to a stimulus from the situation or project manager. The low end of the scale represents behavior that is counter to the goal of acting for project success; actions taken at this end of the scale reduce the likelihood of project success.

FIGURE 1-2: Executive Measurement Model

The Executive Ability axis is a continuous range representing the project management-related ability of the executive. At the high end of the scale, executives are characterized as being adept at not only the management of projects but also at the management of the organization in which the project resides; organizational change is a skill possessed by these executives. The midpoint on the scale pertains to executives who have a full set of skills to manage within the bounds of a defined project but who are not equipped to impact the organizational environment in which the project is located. The low end of the scale represents executives who, although they may possess a significant range of skills, are not able to manage projects or impact the project environment.

By using the Executive Support for Projects Model, the project manager can gauge both the executive’s attitude and ability. Taken together, these two dimensions serve as the basis of understanding needed to allow the project manager to help the executive overcome the barriers and accelerate support for project success. The resulting executive supports for project behaviors are as follows:

| Executive Behavior | Project Manager Acceleration Approach | |

| Initiator | Proactive attitude and organizational project management ability. Concern for taking actions for project success. Thorough knowledge of the management of projects within the organizational context. High motivation to use foresight to identify upcoming opportunities. | Full and open communications with executive to ensure that actions for project success are synchronized. |

| Inelegant | Proactive attitude and non-project management ability. Concern for taking action for project success, but without the benefit of needed understanding about project management. Likelihood of well-intentioned actions being taken that are less than effective. | Take the lead to identify the actions for the executive to take and help executive take those actions. |

| Competitor | Counteractive attitude and organizational project management ability. Agendas counter to project success. Thorough knowledge of the management of projects within the organizational context. Likely to subjugate project management to achieve competing agenda. | Keep well informed of the executive’s actions and look for common ground to reduce the level of competition. |

| Obstacle | Counteractive attitude and non-project management ability. Concern for agendas counter to project success, but without the benefit of the understanding needed for project management. Likelihood of somewhat random and unpredictable behavior that may or may not impact project success. | Insulate the executive, form alliance with a more supportive executive, and raise the opposing executive’s project management knowledge level. |

Study all areas of your projects, and identify where you might have cut corners, compromised, or let people down.

Study all areas of your projects, and identify where you might have cut corners, compromised, or let people down.