Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Cornerstones of Engaging Leadership (with CD)

Casey Wilson (Author)

Publication date: 01/01/2008

The traditional command-oriented leadership style is not enough to keep today's employees motivated—they need to be engaged. They need passion, connection, and inspiration, and a willingness to put forth their best efforts to benefit themselves and their organization.

The Cornerstones of Engaging Leadership connects what we know about engagement on an organizational level to what an individual leader can do to increase engagement. Using real-world examples, Wilson reveals the key actions leaders must take to connect with and engage others:

•Build trust

•Leverage unique motivators

•Manage performance from a people-centric perspective

•Engage emotions

By committing to these four cornerstones of engaging leadership, leaders can unleash the potential of others and inspire effective performance. Through practice tools and exercises, readers are challenged to explore, reflect upon, and apply key concepts and techniques of the engaging leader approach.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

The traditional command-oriented leadership style is not enough to keep today's employees motivated—they need to be engaged. They need passion, connection, and inspiration, and a willingness to put forth their best efforts to benefit themselves and their organization.

The Cornerstones of Engaging Leadership connects what we know about engagement on an organizational level to what an individual leader can do to increase engagement. Using real-world examples, Wilson reveals the key actions leaders must take to connect with and engage others:

•Build trust

•Leverage unique motivators

•Manage performance from a people-centric perspective

•Engage emotions

By committing to these four cornerstones of engaging leadership, leaders can unleash the potential of others and inspire effective performance. Through practice tools and exercises, readers are challenged to explore, reflect upon, and apply key concepts and techniques of the engaging leader approach.

Casey Wilson, former Leadership and Management Practice Leader for Management Concepts. In this role, Mr. Wilson leveraged his leadership expertise and background in consulting, adult learning, and instructional design to help others enhance their leadership capabilities. He also served as an adjunct faculty member at Montgomery College in Maryland, teaching courses on such topics as building high-performance work teams, employee performance and conduct, and performance management.

CHAPTER 1 Engaging Leadership

It is imperative that leaders understand what engagement is, what engaging leadership is, how it can be used to foster engagement, and why engagement is critical to leaders and organizations. Engagement can be defined as a state of passion, connection, and motivation, and a willingness to give your best efforts to benefit yourself and your organization. Engaging leaders build trusting relationships, leverage unique motivations, take a people-centric approach to managing performance, and emotionally engage others. Engaging leadership gets the best results when it inspires others to use their discretionary effort in a way that is meaningful, positive, and results-oriented for the individual, the leader, and the organization.

You may be thinking, “This engagement stuff is only for executives or high-level leaders.” After all, the far majority of literature on engagement focuses on data obtained at the organizational level. This data is mostly concerned with turnover and retention. While it is true that every executive- and high-level leader should pay attention to the engagement levels within their organization, leaders at every organizational level can influence engagement. This includes formal supervisors as well as those who take the lead in project teams, work groups, and in other co-worker interactions. Regardless of role or rank, all professionals have the ability to positively influence their interactions with others.

Understanding and Exploring Engagement

Engagement is a state of being passionate, connected, motivated, and willing to give your best efforts to benefit yourself, your leader, and your organization. Every individual is engaged in some way, although their level of engagement may vary. The three different levels of engagement can be viewed on a continuum (see Figure 1-1). On one end of the continuum individuals are engaged, while on the opposite end of the continuum, individuals are actively disengaged.

The Engaged Individual

Engaged individuals leverage their strengths to help themselves become high achievers. They proactively build relationships with others. They demonstrate commitment to their own development and success, the success of others, and the success of their organization. Engaged individuals have high aspirations, and they work positively and proactively to better understand their assignments and excel in them. When assignments are not available, they create work for themselves by volunteering for additional tasks. Energetic and enthusiastic, engaged individuals always seek to improve their effectiveness. They foster and facilitate conditions that contribute to their own success and to the success of others. An engaging environment is a catalyst for individual, group, and organizational success. Employee engagement can even drive customer engagement, stemming from highly positive and enjoyable experiences with engaged individuals.

FIGURE 1-1 Engagement Continuum

Consider a time when you felt really tuned into your work, a time when you had a great relationship with a supervisor that was built on mutual trust. Your supervisor gave you challenging assignments and rewarded you in ways that made you feel valuable. In essence, the supervisor knew how to inspire your best effort and performance. By working together, you fed off of each other‧s excitement and energy. In other words, you were engaged in your work.

The Non-Engaged Individual

Non-engaged individuals are neither actively engaged nor actively disengaged; they are neutral. Non-engaged individuals do not invest much effort in going the extra mile for themselves, nor for internal or external customers. They tend not to be innovative. And while they do not necessarily work against their organization, they do not proactively work to better it either. Many just hang out, biding their time day-in and day-out, simply riding the work wave.

Non-engaged individuals make up the majority of the modern workforce. Because this group is simply floating along, they are the group with the most potential to become engaged. Leaders should spend the most effort trying to engage this group of people. This potential exists because these individuals are not frustrated and jaded, as are actively disengaged employees. Instead, they haven‧t had a leader who sparked their sense of passion and excitement.

Visualize a teeter totter—one of those dizzying playground rides where kids ride up and down until they practically fall off. If engaged individuals are the ones who are “up,” and actively disengaged individuals are “down,” non-engaged individuals are right in the middle. Their ups and downs are not quite as dramatic. However, because of their neutral position on the teeter totter, they can potentially slide to either side—up or down. Leaders have the potential to engage this group in the middle so that they join side that‧s “up.”

The Actively Disengaged Individual

Actively disengaged individuals thrive on negativity. They give the minimum amount of effort possible because they perceive that nobody cares about them or what they do at work. They arrive each day, perform a little work—typically work of lower quality compared to engaged individuals—and leave. They display negativity by complaining and nagging. They are purposely contrary, often going against the grain. When given feedback, they ignore it. Actively disengaged individuals let everyone know about their unhappiness, and some even try to perpetuate negativity in hopes of getting others to join them—sort of a “misery loves company” perspective.

Active disengagement occurs when individuals feel they work under negative or toxic work conditions, perceive their supervisors to be insensitive, and have unmet emotional needs. They feel subjected to office politics that distract them from their goals, or they feel they are not receiving individual attention in a meaningful way. This lack of personalized attention can cause resentment and be a catalyst for “checking out” of work.

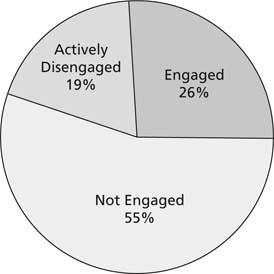

Current data suggests that most individuals working in organizations are not actively engaged (see Figure 1-2).1 The percentages in this figure were determined by an informal meta-analysis of three different studies on engagement by three different organizations.

FIGURE 1-2 Employee Engagement Percentages in Organizations

Looking at the percentages of people within a given workforce, there are a number of interesting points:

Only about one-fourth of people are passionate, committed, and connected to their work.

Only about one-fourth of people are passionate, committed, and connected to their work. What is worse, about one-fifth of people are working against their organizations through active disengagement!

What is worse, about one-fifth of people are working against their organizations through active disengagement! Setting aside those two ends of the continuum, over half of people are simply floating through their work days, not working against their organizations but also not feeling connected and committed.

Setting aside those two ends of the continuum, over half of people are simply floating through their work days, not working against their organizations but also not feeling connected and committed. Knowing that engaged people give their best work to their organizations, about three-fourths of people have some amount of discretionary effort they are not giving to their organization or their leader.

Knowing that engaged people give their best work to their organizations, about three-fourths of people have some amount of discretionary effort they are not giving to their organization or their leader.

Discretionary effort is the amount of energy kept in reserves that someone chooses to use or not depending on how they feel about their work. Every person has a certain amount of discretionary effort. High performers bring plenty of discretionary effort to the table, and most leaders wish all their colleagues brought just as much.

Everyone has a certain amount of discretionary effort they can choose to deliberately leverage—or not leverage—on behalf of their leader.

PRINCIPLE

Engaging leaders believe in people. It is people and their use of discretionary effort that differentiate high-performing organizations from the rest.

Leaders who successfully engage people can tap into their discretionary effort. Without draining that reservoir of discretionary effort, engaging leaders find ways to replenish it. Think of engagement and discretionary effort as renewable resources. With an engaging leader, people are inspired to achieve more. For many organizations, the quality, commitment, and passion of their employees drives the effort to accomplish all missions.

Engaging leaders must believe in people. Today, individual talent and a willingness to exert discretionary efforts differentiate successful organizations from the rest.

EXERCISE

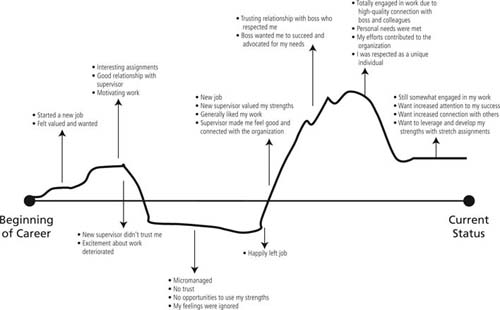

When Have You Been Engaged? (Using a Career Line)

In order for leaders to engage others, they must be engaged themselves. This is important because individuals who have engaged supervisors are more likely to be engaged themselves, and they are also more likely to understand what it takes to be engaged. That said, non-engaged supervisors will find it difficult to engage others.

This exercise can help you better understand your own levels of engagement throughout your career. The objective is for you to consider periods of your career when you were engaged or disengaged, and why.

First select a period of time to analyze (e.g., the past five years of a current position). The straight printed line represents the time when you were not engaged. Now draw peaks and valleys relative to the printed line: peaks for times when you were highly engaged, parallel lines for times when you were not engaged but not actively disengaged, and valleys for times when you were actively disengaged. Label those peaks and valleys. Take a few minutes to note why you were engaged at those peak times. Make notes similarly for times when you were non-engaged or actively disengaged.

Example:

Beginning Today

Analyzing Your Career Line

Look at the peaks on your career line. What made those moments high points in your career? What was it about the organization, and more specifically, about your leader, that helped you reach those points? How did your leader help you? What was the relationship like?

Now consider the valleys on your career line. Why were they low points? What did the organization or leader do to contribute to those low points? What do you wish they would have done differently?

Similar to the stock market, individual engagement levels may go up and down depending on the amount of energy and time invested in the person. Consider the leaders who have taken the time to invest in you. How do those experiences relate to your job satisfaction at the time? What about the leaders who only took your hard work without investing anything back into you? It‧s very likely that those experiences relate to the low points on your career line and were times when you wanted to be engaged, but were not. Engaging leaders create meaningful connections and invest in the successes of others.

How to Increase Engagement

Individuals can become engaged in two ways: through self-directed engagement and through engaging leadership. For most, sustaining self-directed engagement requires the personal connections that come from an engaging leader. Individuals ultimately choose how to use their discretionary effort, but leaders should seek out and facilitate mutually beneficial ways to inspire them to use such effort. Engaging leadership is about tapping into an individual‧s potential to allow greater and more satisfying results for themselves, their leaders, and their organizations.

Through intentional actions and specific behaviors, leaders can increase engagement and tap into the discretionary energy of others. It is important to for leaders to recognize that both their abilities and their rapport with others directly influence success levels. The stronger the interpersonal connection, the better the chance a person will be willing to engage.

PRINCIPLE

A strong interpersonal connection with a leader is the primer for individual engagement.

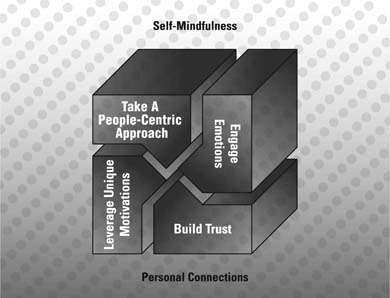

Developing strong interpersonal connections requires leaders to have a biopic perspective. Through one lens leaders are mindful of their intentions, actions, and behaviors; through the second lens, they create personal connections and relationships with others.

The First Lens: Self-Mindfulness

The engaging leader approach is built on mindfulness of self and of others. Being mindful is being aware of internal thoughts, feelings, emotions, and reactions. It is also being aware of the thoughts, feelings, emotions, and reactions of others. Being mindful means listening to an inner voice and willingly and intentionally finding ways to connect with others on a meaningful, personal level.

Self-mindfulness is important to engagement for a number of reasons. First and foremost, leaders are the primary role model for others—and people do monitor their leaders’ engagement levels. While this monitoring may not be explicit or intentional, people nevertheless pick up on their leaders’ engagement vibes. They notice levels of trust in the organization, methods of managing performance, and levels of emotional engagement. The more leaders engage, the more likely they will be to inspire others to engage. Therefore, it is critical for leaders to monitor their own level of engagement to make sure it models well for others.

The second reason mindfulness is important is because in order to truly engage others, a leader must get to know and understand them. Self-exploration gives a leader practice at finding an inner voice and deeper thoughts and emotions. It requires leaders to ask themselves some challenging questions about the implications of trust or distrust in their own work relationships; about their preferences when others manage their performance; and about the extent to which they are emotionally connected to their work. Once leaders know themselves well, they are more likely to empathize with others as they explore and articulate their own needs. Asking themselves challenging questions will make it easier to ask others the same kinds of questions.

While it is not easy, leaders can become more mindful through self-awareness, self-understanding, and self-management. Self-awareness occurs as leaders become aware of personal opinions, thoughts, feelings, preferences, and heuristics. Heuristics are unconscious routines that individuals develop in their lives. They are hard-wired into the brain, and because of this, people often fail to recognize them. Instead, they often believe that everyone shares their world view and sees things the same way as themselves. Just recognizing that these tendencies exist is the first step toward understanding them and their influence on individual thoughts and actions.

Self-understanding occurs when leaders take their self-awareness and known heuristics and explore them to better comprehend how they shape personal perspectives, character, and leadership approaches. Understanding their own leadership approach allows leaders to actively and consciously make choices about how to interact with others. It can also facilitate a better understanding of how others perceive their leader. This kind of self-understanding is necessary for leaders to achieve congruence between who they are and who they want to be.

The congruence that an individual seeks as a leader happens through action, which is where self-management takes place. If awareness is the internal recognition of yourself and understanding is the internal comprehension of it, then self-management is the part most visible to others. This is because people more easily recognize actions and behaviors (as opposed to thoughts). For example, if a leader is consistently playing to peoples’ strengths, it will likely be noticed. These visible behaviors allow leaders to build more effective and engaging relationships.

Getting to know yourself can be a scary process, but it does not have to be. Think of it as an iterative process over time. Individuals live and learn, which requires their perspectives, preferences, opinions, and approaches to evolve with time.

Engaging leaders can take advantage of many ways to develop self-awareness and self-understanding, each of which is a step toward more effective self-management. Self-assessments are a great place to start. Effective self-assessments provide a framework for learning about yourself, and yourself in relation to others. Some particularly helpful self-assessments include:

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator(r) (MBTI(r))

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator(r) (MBTI(r)) Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation-Behavior(tm) (FIRO-B(r))

Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation-Behavior(tm) (FIRO-B(r)) SPEED of Trust(r) Audit

SPEED of Trust(r) Audit Emotional Intelligence Self Appraisal(tm)

Emotional Intelligence Self Appraisal(tm)

In addition to self-assessments (which risk incorporating significant amount of personal bias when individuals lack self-awareness or are not honest about personal shortcomings), multi-rater assessments, such as a 360-degree feedback assessment, are quite valuable. Multi-rater assessments allow participants to recognize personal traits they may not have been aware of previously. Being aware of these blind spots and understanding them can lead to increased congruence between personal thoughts and corresponding actions or behaviors. It may also highlight the need for self-work. The self-awareness that comes as a result of these assessments often requires individual flexibility and a willingness to adjust previous leadership approaches.

Engaging leaders can become self-aware in other ways as well. For example, journaling can be helpful in capturing a state of mind, including thoughts on physical and emotional reactions to situations. However, journaling is only helpful if writers revisit and explore their entries and learn from them afterwards. Thinking about what happened and why can be insightful, and if done with an open mind, can lead to greater self-understanding and more effective choices.

Another way to become more self-aware is to have open discussions and forums on important topics. Numerous topics can generate thought-provoking discussions, including personal leadership philosophies, past practices from leaders who did or did not engage people, what people like and dislike most about their work as a leader, the role that trust plays in working with others, what unique motivators each person has, and how people prefer to be managed. These discussions can help participants discover other helpful points of view.

Forging personal connections with others also requires that leaders be genuine and be perceived as genuine. Only through honest, direct, and genuine conversations can leaders engage others.

PRINCIPLE

To be authentic and genuine, you must understand who you are (and who you are not) and who you want to be as a leader.

Former PepsiCo CEO Roger Enrico said, “Beware of the tyranny of small changes to small things. Rather, make big changes to big things.” Becoming an engaging leader may mean making big changes, and it is a choice each leader has to make. Engaging leaders do not cheapen themselves by simply going through the motions; instead, they buy into the importance and value of self-mindfulness and authenticity when working with others. Being social is a part of that authenticity and a part of the human experience. Sometimes leaders lose sight of the need for human connection. Becoming engaging may require a willingness to reconnect with the human side of the workplace or in some cases to reinvent one‧s self with a renewed sense of conviction to be authentic and genuine.

“One day, out of nowhere, you realize you don‧t know who you are, and none of the cards in your wallet provide the slightest clue to your real identity.”

— SAM KEEN, FIRE IN THE BELLY

The Second Lens: Creating Personal Connections and Relationships

Through the second lens, leaders must view personal connections and relationships as the primary vehicle for engaging others. This may require a fundamental paradigm shift in the way leaders think about their colleagues: Rather than think about their colleagues only as knowledge workers, they must recognize them as human beings who have personal goals, desires, and needs. This makes creating connections and building relationships critical. If leaders want their colleagues to be loyal and committed, they must reciprocate that loyalty and commitment. The only way to achieve this is through meaningful, positive personal connections and strong relationships.

Leaders must take four key actions to connect with and engage others. These key actions are the four cornerstones of engaging leadership:

Build trust as the foundation of effective relationships.

Build trust as the foundation of effective relationships. Motivate individuals in ways that are uniquely meaningful to them.

Motivate individuals in ways that are uniquely meaningful to them. Take a people-centric approach to managing performance.

Take a people-centric approach to managing performance. Engage the emotions of others in their work.

Engage the emotions of others in their work.

Engaging leaders demonstrate self-mindfulness while creating personal connections with others. Each of the four cornerstones of engaging leadership involves self-mindfulness and creating personal connections.

Each of the subsequent four sections of this book is dedicated to one of the cornerstones of engaging leadership. Leaders can become more effective by making any one of these a serious priority But by separating the cornerstones, an important element is lost. Combining these principles through the lens of engagement will unleash the true potential of others and inspire effective performances and an amazing sense of pride and commitment, enabling individuals and organizations to achieve their best results.

By building trust, understanding unique motivations, managing performance from a people-centric perspective, and engaging emotions, engaging leaders can tap into the true potential of others. This humanistic approach creates situations where engaging leaders, their colleagues, and their organizations all benefit. By shifting a paradigm of what it means to lead others, engaging leaders can create connections and ensure success at all levels of an organization.

If leaders want to fully engage others, they must recognize each individual‧s unique needs and preferences. To use an analogy, engagement is like food and each of the four cornerstones of engaging leadership is a bite of nourishment. Individuals want and need different portions, and they are hungry for them at different times. Some prefer smaller bites of many different foods, while others prefer large bites of a single kind of food. Some individuals want the sampler platter, while others want to gulp down the entire meal! No preference here is necessarily right or wrong, only more or less satisfying for any given person.

“Nobody can prevent you from choosing to be exceptional.”

— MARK SANBORN, THE FRED FACTOR

PRACTICE TOOL

Exploring the Engagement of Others

This tool offers a series of questions to help determine whether you are engaging others. Each of the questions correlates with a specific cornerstone of engaging leadership. You may already know in your heart whether or not you are engaging others, but if you do not know or if you want to confirm your suspicions, this questionnaire provides a good way to start thinking about it.

Think about your current team or the group of people you currently influence. List their names here:

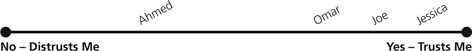

Below each of the following questions is a continuum. For each question and its respective continuum, consider the question and write someone‧s name on the continuum in the appropriate place. Instead of thinking of your responses as right or wrong, think of them in terms of more or less.

Example:

Q. 1 Can you say with confidence that this person trusts you?

BUILDING TRUST

Q. 1 Can you say with confidence that this person trusts you?

Q. 2 Can you describe the three most personal motivators for this person?

ENGAGING EMOTIONS

Q. 3 Do you feel comfortable expressing emotions with this person at work?

A PEOPLE-CENTRIC APPROACH TO MANAGING PERFORMANCE

Q. 4 How often do you give recognition to this person?

LEVERAGING UNIQUE MOTIVATORS

Q. 5 How well do you know this person‧s interests outside of work?

A PEOPLE-CENTRIC APPROACH TO MANAGING PERFORMANCE

Q. 6 When was the last time you complimented this person for a specific strength they possess?

A PEOPLE-CENTRIC APPROACH TO MANAGING PERFORMANCE

Q. 7 How often do you ask this person for their opinion?

A PEOPLE-CENTRIC APPROACH TO MANAGING PERFORMANCE

Q. 8 How often do you intentionally give assignments that leverage this person‧s strengths?

LEVERAGING UNIQUE MOTIVATORS

Q. 9 When was the last time you explicitly discussed motivation with this person?

A PEOPLE-CENTRIC APPROACH TO MANAGING PERFORMANCE

Q. 10 When was the last time your gave this person honest, direct feedback about his or her performance?

ENGAGING EMOTIONS

Q. 11 According to your perception, how interested is this person‧s in his or her work?

This exercise is not meant to highlight your particular skills or abilities as a leader; it simply provides a way to begin thinking about how you engage others. Your responses to these questions should provide some insight into your level of engaging leadership with the people you listed.

Each of the questions above correlates with a specific cornerstone of engaging leadership. If you find that you are not practicing one of the cornerstones, pay special attention to the particular chapter of the book to get practical tips and techniques for improvement. Then again, you may find that you are already engaging others fairly well. Depending on how your responses fell on the continuum, you may have additional opportunities to engage others.

ENDNOTE

1. Data was gathered from: The Gallup Management Journal (The Gallup Organization, The Gallup Management Journal, http://gmj.gallup.com/default.aspx.); The Corporate Leadership Council (The Corporate Leadership Council, Engaging the Workforce: Focusing on Critical Leverage Points to Drive Employee Engagement (Washington, D.C.: The Corporate Executive Board, 2004)); and Developmental Dimensions International (Paul Bernthal, Ph.D., Richard S. Wellins, Ph.D., and Mark Phelps, Employee Engagement: The Key to Realizing Competitive Advantage (Pittsburgh: Developmental Dimensions Internation, Inc., 2005).

RECOMMENDED READING

Boyatzis, Richard E., and Annie McKee. Resonant Leadership: Renewing Yourself and Connecting with Others through Mindfulness, Hope, and Compassion. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2005.

Carlson, Peg, Anne Davidson, Sue McKinney, and Roger Schwarz. The Skilled Facilitator Field Book: Tips, Tools, and Tested Methods for Consultants, Facilitators, Managers, Trainers, and Coaches. San Francisco: Tossey-Bass, 2005.

Senge, Peter. The Fifth Discipline. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

Senge, Peter. The Fifth Discipline Field Book. New York: Doubleday, 1994.