Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Extraordinary Power of Leader Humility

Thriving Organizations Great Results

Marilyn Gist (Author)

Publication date: 09/22/2020

—Ken Blanchard, coauthor of The New One Minute Manager and coeditor of

Servant Leadership in Action

On the most fundamental level, leaders must bring divergent groups together and forge a consensus on a path forward. But what makes that possible? Humility—a deep regard for the dignity of others—is the key, says distinguished leadership educator Marilyn Gist.

Leadership is a relationship, and humility is the foundation for all healthy relationships. Leader humility can increase engagement and retention. It inspires and motivates. Gist offers a model of leader humility derived from three questions people ask of their leaders: Who are you? Where are we going? Do you see me? She explores each of these questions in depth, as well as the six key qualities of leader humility: a balanced ego, integrity, a compelling vision, ethical strategies, generous inclusion, and a developmental focus.

Much of this book is based on Gist's interviews with a dozen distinguished leaders of organizations such as the Mayo Clinic, Costco, REI, Alaska Airlines, Starbucks, and others. And the foreword and a guest chapter are written by Alan Mulally, the legendary leader who brought Ford back from the brink of bankruptcy after the 2008 financial collapse and whose work is an exemplar of leader humility.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

—Ken Blanchard, coauthor of The New One Minute Manager and coeditor of

Servant Leadership in Action

On the most fundamental level, leaders must bring divergent groups together and forge a consensus on a path forward. But what makes that possible? Humility—a deep regard for the dignity of others—is the key, says distinguished leadership educator Marilyn Gist.

Leadership is a relationship, and humility is the foundation for all healthy relationships. Leader humility can increase engagement and retention. It inspires and motivates. Gist offers a model of leader humility derived from three questions people ask of their leaders: Who are you? Where are we going? Do you see me? She explores each of these questions in depth, as well as the six key qualities of leader humility: a balanced ego, integrity, a compelling vision, ethical strategies, generous inclusion, and a developmental focus.

Much of this book is based on Gist's interviews with a dozen distinguished leaders of organizations such as the Mayo Clinic, Costco, REI, Alaska Airlines, Starbucks, and others. And the foreword and a guest chapter are written by Alan Mulally, the legendary leader who brought Ford back from the brink of bankruptcy after the 2008 financial collapse and whose work is an exemplar of leader humility.

CHAPTER ONE

Leading as Relationship

Leadership is about inspiring people to do what’s needed. If you look over your shoulder and no one’s following you, you are not a leader.

—Roger Ferguson, president and CEO, TIAA

Leadership requires working together. Being in relationship and working with others is how we make progress. And a leader’s biggest challenge is to inspire in others their enthusiastic engagement with a shared goal, whether that is to launch a new product, advance an important cause, improve financial performance, or resolve global challenges.

So how can leaders work most effectively with others? When we think about factors that drive organizational performance, we tend to think about innovation, capital, and strong competitive strategy. When we talk about motivating people, conversation typically turns to rewards and compensation. Largely unnoticed is leader humility—an extraordinarily powerful way of influencing those around you to volunteer their full support to achieving shared goals. Collins (2001) demonstrated that the best results were achieved by organizations whose leaders combined strong drive with personal humility, but some leaders find the idea of humility to be at odds with strong leadership. They think of humility as meekness or weakness and see it as a deficiency, overlooking its real promise.

What if we consider humility in terms of certain behaviors? Because leadership requires working together, what if we consider humility in terms of how we relate to others? Let me define it in a way that is relevant for everyone who leads:

Leader humility is a tendency to feel and display a deep regard for others’ dignity.

We can still be strong and have high standards. And we can demonstrate respect for others’ sense of self-worth.

Leaders Create the Container

Leader humility—supporting others’ dignity—improves working together because it is the essential foundation for healthy relationships. Leaders create the container for how work is done. A physical container is an object in which we hold, mix, or store something. In a similar way, leaders create the environments or cultures in which we do our work: the people, processes, and practices for how we interact.

Leader humility is the container for healthy relationships with all stakeholders (such as direct reports, coworkers or bosses, legislators, media, vendors, community leaders, or customers). When leaders display humility, a tendency to regard others’ dignity as important, the container created for work emphasizes respect for everyone. Interactions become comfortable, and information is freely shared. Because working together is enjoyable, people are motivated to collaborate on shared goals.

When leaders lack humility, when they frequently disregard others’ dignity, the container for work becomes unhealthy. Simply put, violating others’ dignity harms relationships. Those who feel disrespected become cautious around the leader, sometimes withholding important information if they feel the leader is critical of them. As resentment grows, stakeholders are less inclined to lend their full support. Working together suffers as tensions build. Progress slows and political behavior often grows.

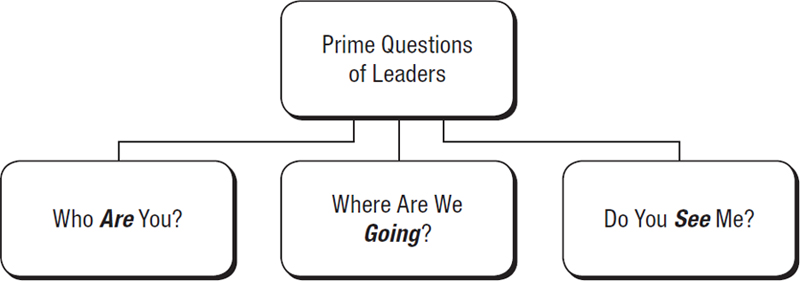

Stakeholders have their own important worries—things like fairness, the amount of change they are being asked to embrace, and their own personal goals. When you think about it, people have three prime questions when facing a new leader (see figure 1). Whether they are asked aloud or merely observed, others evaluate leaders on these dimensions when deciding whether they want to follow along and to what extent.

Curiosity about these questions flows from the observers’ personal concerns and is tied to their core sense of dignity, or self-worth. When the answers are favorable, people grow inspired and eager to engage with a leader. Favorable answers allow the leader to connect with the whole person—mind, heart, and spirit—so that people want to join in the quest and give it their all. Yet when the answers are unfavorable, people tend to withdraw or resist.

FIGURE 1. Three Prime Questions People Have of Leaders.

Has it always been like this? Were these questions always important? Or has something shifted over the past decade or two?

The challenge comes from society’s expectations of a traditional leader. The top three words that we think of for leaders would include things like “accomplished,” “decisive,” “strong.” We think of leaders as action-oriented, driven, type A people. These are very different times. Leaders are being put more into glass houses than ever before. We are being scrutinized, called to task more, and held accountable. People can go on Glass Door to rate their leader. —PHYLLIS CAMPBELL, CHAIRWOMAN OF JPMORGAN CHASE, PACIFIC NORTHWEST

I do think it’s changing now. There’s a lot more focus on transparency in leadership. The presence of the internet is making that happen because people can quickly report what’s going on. Because they can tweet or email, we can see inside organizations. So, there’s a shift away from being autocratic toward more servant leadership. Still, there are way too many leaders using the older approach. —HOWARD BEHAR, FORMER PRESIDENT OF STARBUCKS COFFEE COMPANY INTERNATIONAL

Is there evidence that most leaders are missing the mark? There is. In a consolidated report, Forbes Councils (Castle 2018) shared results from multiple surveys they had conducted of their communities of prominent executives and entrepreneurs. The results identified leadership as the number three challenge facing business executives (just behind generating revenue and time). Leadership was found to be the single most significant concern by 57 percent of Forbes Human Resources Council, 50 percent of Forbes Nonprofit Council, and 38 percent of Forbes Technology Council. Leadership dominated the concerns among executives in computer and technology industries (36 percent) and was named as the most important concern among VPs (33 percent) and C-suite executives (30 percent). Finally, leadership was identified as the greatest challenge by 42 percent of executives in companies with fifty-one to five hundred employees—a substantial portion of the US private workforce. So, what the executives in Forbes Councils know is that our collective competence in leadership is far below what we need to manage the business challenges at hand.

You might be wondering if this applies to you and how it relates to leader humility. Let me share just two examples of leadership challenges that affect productivity in most organizations: evidence on low employee engagement and turnover costs:

1. In a random sample of more than thirty thousand employees, Gallup (Harter 2018) reported that US employee engagement had risen to 34 percent—still quite low, but the highest level since it began reporting on this. Thirteen percent of employees reported being actively disengaged (indicating miserable work experiences), and 53 percent were “not engaged.” In other words, 66 percent of employees were described as not being “cognitively and emotionally connected to their work and workplace; they will usually show up to work and do the minimum required but will quickly leave their company for a slightly better offer.” This results in a huge loss of potential productivity—not only because of the minimal performance of this 66 percent but also because of the negative effect they often have on others’ work and the culture in the workplace. The fact that nearly two-thirds of employees are doing the minimum required on their jobs (and are willing to leave) implies that most leaders are not creating healthy containers for working together. Because leader humility is the container for healthy relationships, this poses a significant opportunity: imagine the productivity gain if we could generate even 20 to 30 percent more employee engagement with our collective goals.

2. Talent matters. And attracting and retaining talent is another important leadership issue. McKinsey & Company (2017) reported that top talent can provide a 400 to 800 percent boost in productivity over that of average employees, with the wider gap pertaining to jobs with high complexity (such as software developers, top medical professionals, and managers dealing with complex information or interactions). Yet the best employees have the greatest opportunity to leave. When leaders understand how to recruit and retain talented employees, there is a significant upside benefit. Unfortunately, many do not recognize the importance of leader humility for this. For example, in a large-scale study of departures, Work Institute (Sears 2017) found that 75 percent of the reason employees leave (including workplace culture and leader behaviors) could have been prevented by managers. In other words, most turnover is caused when leaders create unhealthy containers. This significantly affects the bottom line: Catalyst (2018) estimated turnover costs at $536 billion per year in the United States. This reflects the costs of recruiting, onboarding and training, weak engagement while employed, and loss of productivity from the unfilled role.

In addition to these examples, new demands on business leaders are requiring them to expand their leadership competence. Addressing these effectively will require working together. Economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic presents new challenges, as well as new opportunities, as industries reshape themselves. Leaders face dramatically new financial needs and competitive forces, as well as large-scale job displacement and the need for retraining employees. Technologies like artificial intelligence and genetic science also are poised to cause major changes in work and markets in the coming decade. And urgent factors at the interface between business and society are greatly affected by commerce, calling for business leaders who can represent and integrate the interests of all stakeholders. These include the impact of travel on global health, climate change, trade imbalances, wealth disparities (and resulting political instability), globalization of markets and backlash against immigration, and the use (abuse) of communications technology.

Although some challenges affect certain businesses more than others, it will be important for all leaders to guide their organizations in new ways. Some leaders focus so much on analytical factors involved in optimizing profit margins that they neglect the human factors that are actually driving results. And most important is leader humility because it is the container for healthy relationships—for working together effectively. Fortunately, we do see some leaders making progress in this arena:

On the West Coast, I think we tend to see businesses that align our actions with our values. This has emboldened business leaders to be more values-driven as opposed to simply focusing on shorter-term issues. Airlines are people-based businesses. Investors want high asset utilization and high returns and so forth, and I was drawn to the industry because there is fantastic algebra that a person with an analytical orientation can spend a career optimizing.

But then there’s the human side of the business, and that raises the question of which is more important—the algebra or the culture? I think that people have to win. If they feel you have their back, and you give them the tools to work challenges, they will give it their all, and they will help the business prosper and succeed. That is the reason that Alaska is still here while so many other airlines both larger and smaller than us have failed. It’s our people. —BRAD TILDEN, CHAIRMAN, PRESIDENT, AND CEO OF ALASKA AIR GROUP

So why aren’t more leaders successful? The most promising path to optimizing organizational performance is to get people to align and put their very best energies behind a shared plan. Securing this type of alignment today responds better to leader influence and inspiration than control. Most leaders have vision and drive for results—as well as power. Ordinarily, power is used in one of two ways: through coercion (command and control) or through transaction (rewards and punishment, carrot or stick). This works up to a point but is often limited because people resent being coerced, and they see the transactional approach as somewhat manipulative. Ordinary power can earn the compliance of stakeholders. However, by supporting others’ dignity, leader humility is extraordinarily powerful for engaging others’ hearts and spirits, drawing out their best contributions. Many leaders still emphasize control, because too few understand the power of leader humility to inspire others and navigate the interpersonal dynamics and conflicting opinions on pressing issues. Schein and Schein (2018) called for humble leadership to replace the transactional approach with one that is more personal in order to build more open and trusting relationships.

Creating Gracious Space

Shining a light on this begins by putting ourselves in others’ shoes. Think back to the three prime questions people have about leaders: Who Are You, Where Are We Going, and Do You See Me? Rather than relying on command and control to gain support, or the use of fear and intimidation as motivators, leaders with humility create a more gracious space for the dignity of others. By understanding and honoring the needs of others, leaders with humility gain more support because stakeholders become more engaged.

How do humble leaders do this? The answer begins with recognizing that leaders are always being watched by others. What leaders say and do is scrutinized, and their behavior provides the evidence that answers the three prime questions others have. In aggregate, the answers to these questions form the impression in others’ minds of a leader’s humility. So, although my own opinion of my humility is useful, my stakeholders’ judgments are critical because their assessment determines how well we will work together.

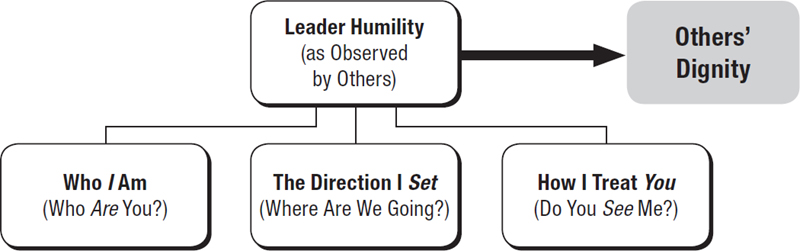

Recalling the three prime questions people have about leaders, let’s consider a mirror image of three prime answers that are provided by leaders. These answers determine whether others find that leader humility exists. Figure 2 previews this relationship and how it affects others’ dignity. It shows that, as a leader, my own behaviors signal “Who I Am” (as a person), so these behaviors provide answers to people wanting to know: “Who Are You?” Similarly, “The Direction I Set” (for others to follow) and “How I Treat You” provide answers to questions about “Where Are We Going?” and “Do You See Me?” As will be developed in later chapters, my interactions with you around those prime questions will either support or weaken your sense of dignity, or self-worth.

To the extent that I create a gracious space for your dignity—a healthy container for working together—you will feel enthusiastic and engaged. And if I damage your dignity, odds are good that you will withdraw your support or resist my leadership. My behavior—and your response to it—will determine how productive we will be together. Therefore, leader humility has a lot to do with how effective a leader can be.

FIGURE 2. Relationships between Leader Behaviors, Leader Humility, and Others’ Dignity.

Leader humility, creating a gracious space for others’ dignity, is a game changer. It is not the only thing leaders need to do, but it is the critical foundation for working well with others. As a great example of this, consider one of the toughest cases of performance management in business history. The best-selling book American Icon, by Bryce Hoffman (2012), chronicles the rescue and turnaround of the Ford Motor Company from near bankruptcy to strong success following the Great Recession of 2008. The hero in this story is Alan Mulally, former president and CEO of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, who took over as CEO of Ford in its decline. Mulally applied a management approach he had developed and used at Boeing, which he calls the Working Together Management System. By using this system, Ford became the only major US automobile manufacturer to survive the threat of bankruptcy during that period without federal bailout money.

Like other strong CEOs, Alan helped Ford craft a compelling vision and comprehensive strategy to move toward success. However, vision and strategy do not go far unless leaders rouse people to join them in implementation. Mulally transformed an organization that was failing (losing $17 billion the year he arrived) into a dynamic one by creating a container for full employee and union engagement with his “One Ford” plan. Along with regular progress reviews, Mulally’s specific approach emphasized what he calls “Expected Behaviors.” These begin with “People first” and “Everyone is included,” and add “Respect, listen, help, and appreciate each other.”

Part of the page-turning excitement in Hoffman’s book comes from his reports of how Mulally earned the trust of jaded employees because he personally delivered and accepted nothing less than these behaviors from everyone on his team. In a short period of time, Mulally galvanized a company of more than three hundred thousand employees to move Ford from failure to profitability, and he was ranked by Fortune as number three among “The World’s 50 Greatest Leaders (2014).”

Mulally shares more about the Working Together Management System in chapter 7. He faced tremendous challenges as he pursued his leadership goals. Do you relate to any of these issues he experienced that negatively affect performance?

• Weak sales/strained customer relations

• People who do not collaborate when they should

• Lackluster morale among employees

• Leaks to the media about internal problems

• Poor alignment with labor unions and their expectations

• Declining brand reputation

• Challenging government oversight

• Managers who intimidate peers or direct reports

• Unreliable information because people are being self-protective

Mulally’s approach of “Everyone is included” showed humility because it acknowledged that others make important contributions and that it takes everyone giving their best to optimize an organization’s results. He also showed deep humility by holding himself and the entire leadership team accountable for behaviors that “respect, listen, help, and appreciate others.” This created a culture where others’ dignity was supported.

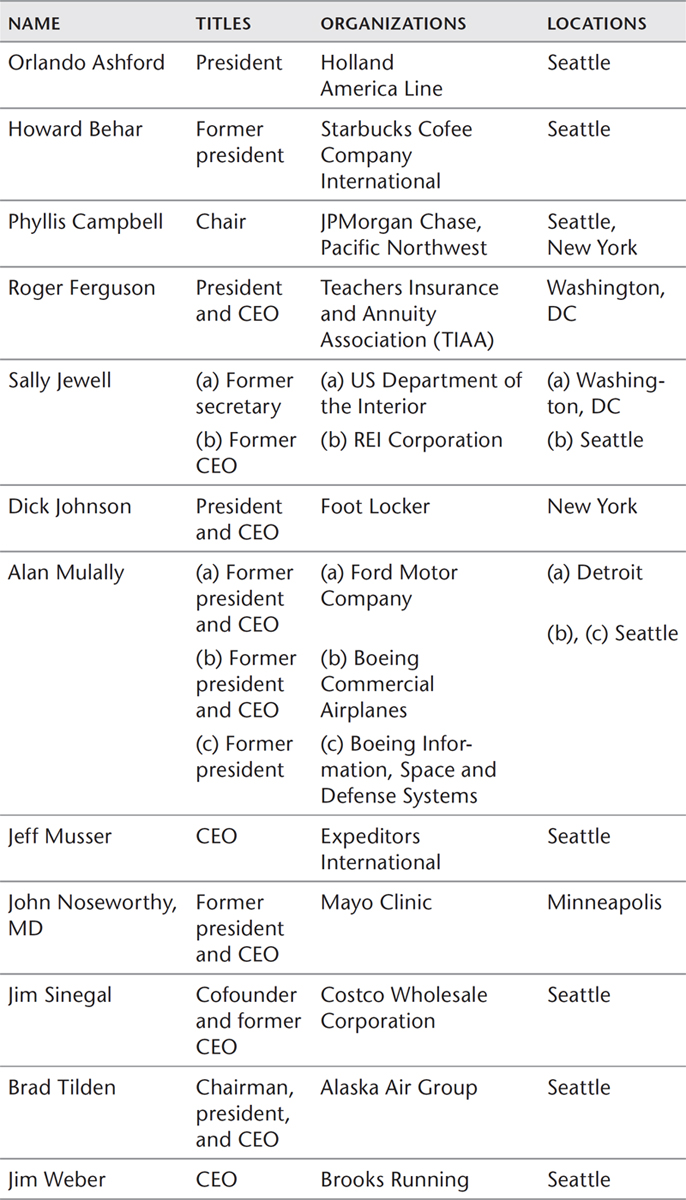

Understanding this dynamic is so important that I personally interviewed a select group of twelve current or former presidents and CEOs. My goal is to show that leader humility is not a minor principle that works only in rare or unusual places, so I need to show its highly successful use in many organizations you will recognize. Although my sample is small, it is robust.

The CEOs interviewed belong to a somewhat rare set of leaders who are commended by employees, peers, and/or press reports not only for excellence but for leader humility. They represent highly successful companies with global reach and widely recognized brand names. In total, the organizations represented here employ hundreds of thousands of people and manage or generate trillions of dollars of revenue each year. These leaders have significant impact on goods and services we consume, contribute substantially to our domestic and global economies, and represent a cross section of industries, government, and nonprofit organizations. Their success is strong evidence that leader humility works.

By default, then, most of these are large businesses. I could have selected from many smaller companies, but they would lack the name recognition needed here. Still, leader humility and working together are relevant to organizations of any size, and chapter 8 specifically explains how the principles that work for these large organizations also apply to small and midsized organizations.

The purpose of this book is to illustrate the value of leader humility. Toward that end, I will be conveying much advice and experience from each of these exceptional leaders. All quotes from them have been taken directly from our interviews. I mention their titles and affiliations only when they are first quoted in the text in order to minimize repetition; subsequent quotes are attributed to them by name only. You have already heard thoughts from three of them in this chapter. Let me provide preliminary introductions to all twelve interviewees in table 1. Chapter 9 briefly shares their exceptional bios, along with personal statements on how they developed the humility that guides them as leaders. Additional information about each of them is available on the internet.

We can assume that leaders and aspiring leaders want to be very effective. And because leaders are typically high achievers, many want to be exceptional. This book holds essential information to help them achieve that. Leader humility improves the employee experience tremendously. This generates higher levels of employee engagement and performance, and lower turnover. And leader humility helps resolve conflicts and forge consensus across stakeholders. Humility also supports a healthy culture of innovation and safeguards a glowing brand reputation. Humility is, in fact, the secret of great success that so many leaders need.

This basic process of creating a healthy container for working together—a gracious space that supports others’ dignity—is so little understood that the next two chapters provide needed explanation. Chapter 2 further explains how humility is a strength, not a weakness. Then it shows humility’s potency and provides a model of leader humility. Importantly, leaders can control their own behaviors and improve organizational performance by displaying favorably who they are (admirable character, such as integrity and balanced ego), setting compelling directions (vision and strategy that is for the greater common good), and treating others well (inclusiveness and developmental focus). Chapter 3 provides a deeper understanding of human dignity and why leader humility is so important for great results.

Let’s pause to consider the following “Ideas for Action” (a section found at the end of most chapters) to help you apply this material to your own situation. Then, as we proceed, let’s draw on the advice and experience of the CEO interviewees listed in table 1.

![]() IDEAS FOR ACTION

IDEAS FOR ACTION

1. What is your most pressing leadership challenge?

2. Assess how well you work together with stakeholders:

a. Make a list of all those affected by your decisions and actions.

b. Where do you draw the boundary for who is inside and who is outside?

c. Are all stakeholders included (inside)? If not, what judgment guides your decision that some are outside?

3. Think of two leaders you follow—one you admire and one you don’t. In what ways have you wondered about them in ways that relate to the three prime questions (Who Are You? Where Are We Going? Do You See Me?)? How did you respond when the answers seemed favorable? Unfavorable?

4. Consider how your stakeholders evaluate those questions about you. Which stakeholders would answer favorably about you? If some would feel unfavorable, what can you do to improve?

TABLE 1. CEO Interviewees and Affiliations.