Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

The Possible Self

A Leader's Guide to Personal Development

Maja Djikic (Author)

Publication date: 03/05/2024

Sometimes success isn't enough—discover how to achieve lasting, whole-life fulfillment through a simple five-stage plan that corresponds with the five key parts of ourselves.

We're often told that the key to success in life involves advancing in our careers, so why do feel stuck and unfulfilled when everything seems to be going right?

Adult development expert Maja Djikic explains that in order to discover our purpose and achieve real, lasting change, we need to move beyond narrowly targeted ideas and strategies like changing our mindset or slightly altering one aspect of our behavior. Instead, we need to go deeper and focus on our innate desires.

Djikic says that sustained change can only happen when our whole self moves holistically the same direction and at the same time. She introduces a transformational system called the Wheel of Change—a simple, five-segment plan that corresponds with the five key parts of ourselves: Desires, Actions, Emotions, Thoughts, and Body.

By understanding the mechanisms of these five integral parts, you will be able to escape the paradox of success without happiness and move towards your own path of fulfilling self-development.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Sometimes success isn't enough—discover how to achieve lasting, whole-life fulfillment through a simple five-stage plan that corresponds with the five key parts of ourselves.

We're often told that the key to success in life involves advancing in our careers, so why do feel stuck and unfulfilled when everything seems to be going right?

Adult development expert Maja Djikic explains that in order to discover our purpose and achieve real, lasting change, we need to move beyond narrowly targeted ideas and strategies like changing our mindset or slightly altering one aspect of our behavior. Instead, we need to go deeper and focus on our innate desires.

Djikic says that sustained change can only happen when our whole self moves holistically the same direction and at the same time. She introduces a transformational system called the Wheel of Change—a simple, five-segment plan that corresponds with the five key parts of ourselves: Desires, Actions, Emotions, Thoughts, and Body.

By understanding the mechanisms of these five integral parts, you will be able to escape the paradox of success without happiness and move towards your own path of fulfilling self-development.

Maja Djikic, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management, the Director of the Self-Development Laboratory, and the Academic Director of Rotman Executive Coaching Certificate program at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto. She has published more than 35 scientific articles and book chapters on personality development, and her research has been featured in over 50 media outlets (including The New York Times, Salon, Slate, and Scientific American Mind). Her corporate clients have included Facebook., McKinsey&Co., Deloitte, Eli Lilly, Royal Bank of Canada, Hyundai Canada, Microsoft, Alcon, and Capital One.

CHAPTER ONE

WHEN THE WHEEL STOPS TURNING

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” This is how Tolstoy begins his masterpiece Anna Karenina. For individuals, we could say the opposite: when joyful, we are all different, moving toward our potential in unique, unreplicable ways. When suffering, we are all alike. With the rest of humanity we feel stagnation; alternate between frantic action and paralysis; suffer frustration and anxiety, rumination and negative self-thoughts; and try hopelessly not to repeat our past failures. We are alike in our suffering because, while our potential and paths are unique, the symptoms of getting stuck appear universal.

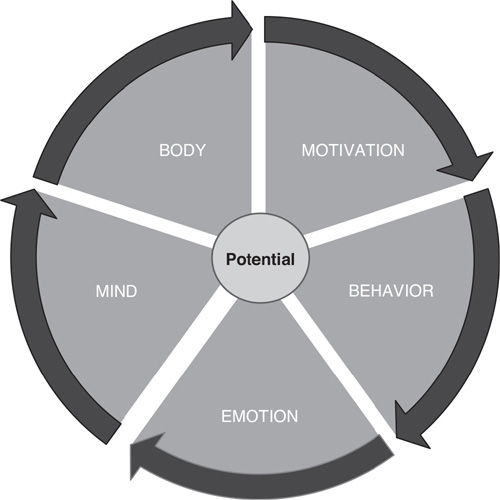

Before we even begin to understand how stagnation happens and how we can leave it behind, we are faced with the big question: What is the self? Ever since Freud divided the self into id, ego, and superego, hundreds of psychologists, sociologists, neuroscientists, anthropologists, and other human-centered professionals have been giving their answers to that question. My own answer, presented in Figure 1.1, is based on observing which “parts” of the self (that recur across many different psychological theories) are most important to people attempting self-change. The model is meant not to be exhaustive but practical, something we can work with to restart our development.

FIGURE 1.1 The Wheel of Self

One way to think of the self is as having five different parts, arranged here into a wheel: motivation, behavior, emotion, mind, and body (the last of which contains learnings from our past).

When most of us try to change (let’s say reduce the number of doughnuts we eat each week), we often focus only on behavior. What we forget is that behavior is influenced by our motivation, that is, our wants and desires (for a delicious Boston cream doughnut), our emotions (the happiness we feel when we taste it), our thoughts (about how fluffy and creamy it will be), and by our body (that has been conditioned by many years of experience to expect a doughnut after lunch). Notice that behavior is governed by other parts of the self. This is why we need to study them in turn.

Just as kidneys, lungs, and intestines would be meaningless to study in isolation without considering an entire organism, so are parts of the self meaningless without understanding the self holistically. Yet just as a medical student would start by learning about different organ systems separately, we will learn (in Part II) what mechanisms govern these different parts of the self. But before that, let us see it in motion—when it moves well and when it stalls.

THE SELF IN ACTION

Imagine you are thinking of leaving your nine-to-five job as a project manager to start a freelancing career. You like the idea of being your own boss, collaborating on interesting projects, and having the flexibility to organize your life more meaningfully. To do this, it’s not enough to change your circumstances. You also need to develop aspects of yourself that are needed for this life transition—how to be disciplined about time, develop confidence and interpersonal skills to offer your services to a wider network of clients, and know when to say no, to prevent burnout.

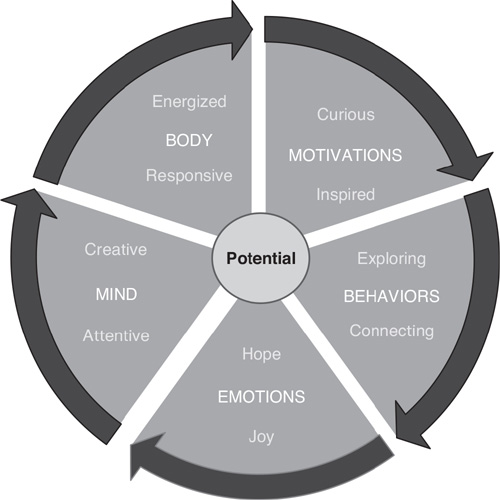

When the Wheel of Self is moving well, all five parts of the self are in harmonious, developmental motion. On the motivational side, you are driven by a curiosity about your subject matter and are inspired to devour materials that will lead you to your aim. Behaviorally, you seek out and explore articles, blogs, and books about freelancing and start connecting with people who are already working and living as you wish to do. The feeling of joy, an emotional signal of developmental movement, permeates your days, and you are excited and hopeful for what your future will bring. Your mind is drawn and attentive to anything to do with your new idea and will often get absorbed in reading articles or watching videos late into the night. Yet, despite the late nights and early mornings, your body feels easily energized, responsive, and restored (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 The Developing Self

When development is going well, all parts of the self work together, seamlessly supporting the change. When in the midst of this process, we don’t have to try to change, apply willpower, or develop habits to keep our new behaviors. It happens organically, as if all parts of the self conspire to develop a new way of being. When the Wheel of Self is moving well, we don’t try to develop, we simply do.

What happens when the Wheel of Self stalls? Abhinav, a 46-year-old physiotherapist, spent his 20-year career working too much. Now he had a full roster of clients and was a managing director of the clinic. He was heavily burdened with both clinical and administrative duties. Most evenings he would come home after his children had already been put to bed. During infrequent family vacations, he would get so anxious and desperate to continue work that more than once his wife suggested he return home early and at least let the children enjoy their few days on the beach. He knew his lifestyle was unhealthy and had tried to change, with no success.

With time, things got worse. He felt he was drifting away from his wife and was not as close to his two children as he wished to be. His health was deteriorating. His practice was full, yet he was still taking on additional patients on recommendation, particularly if they were elderly and had complex rehabilitation needs. In the previous decade, he had tried over and over again to cut down on his work, but his strategies to build new behavioral routines never seemed to work. His friends would tell him, “Just stop working that hard.” Abhinav tried, of course, but his attempts left him feeling guilty, anxious, and broken.

Framing the problem of self-change as that of behavior change is a common misconception about self-transformation. We forget that behavior is influenced by all the other parts of the self: motivations, emotions, thoughts, and old patterns that we carry in our bodies. When we try to change behavior in one direction (trying to work less) while our minds, emotions, and bodies are fighting the opposite tendency (wanting to work more), what we are producing is not a self-change but a form of self-fragmentation. We have tried moving one part of the self while all other parts are stubbornly static or moving in the opposite direction. It is the kind of change that leaves us stressed, exhausted, and full of guilt once we revert to the old behavior. For a successful and lasting inner change, we need all the parts of the self to move together. This is when the self develops organically, without effort.

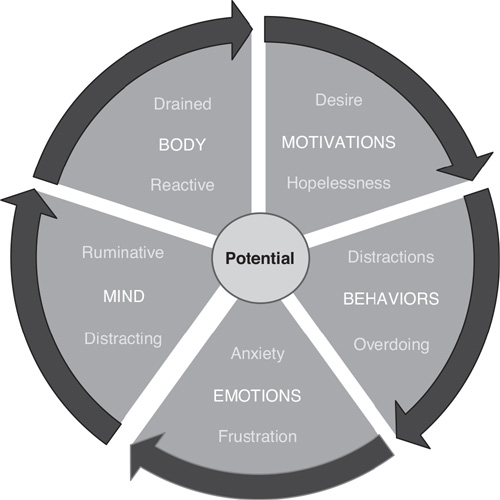

When stalled, however, the parts of the self start doing something very different (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3 The Stalled Self

Motivationally, in terms of wants, instead of thinking of what we want as simply adding to our life, such as wanting to be a free-lancer in the earlier example, we’d think of it as something that would fill a gap in our life. The want may get very intense and may turn into a desire—a chronically unfulfilled goal. This kind of desire does not affect only one part of our life but colors its totality in dark hues. Whenever Abhinav’s strategies to work less failed, he could no longer fully enjoy other parts of his life, whether family, friends, or recreation. During the little time he did spend with his family or friends, he wasn’t able to be fully present. He would drift away mentally, fantasizing about how amazing his life would be if only he could work less. It’s as if the one thing that remained unchanged was a dark cloud over the rest of his life.

This intensification of a want into a desire, punctuated by occasional hopelessness, is a natural motivational outcome of chronically unfulfilled wants. When we don’t get what we want for a long time, we can lose hope, yet even this hopelessness is temporary since the motivational system evolved to press its claims until fulfilled. We can try to stop wanting some change or pretend to ourselves or others that we no longer want it, but the desire would surge again. The motivational system has evolved to continue pulling us forward, despite our trying to give up.

Behaviorally, desire and hopelessness would lead us to alternate between overdoing and distractions. Desire makes us hurry to achieve our goals, and we pour time and energy into self-change. Like a dieter who keeps starting new diets, we would keep overdoing activities that never seem to add up to self-change. At times it would seem we are getting ahead, but these advances would be temporary and opposed by the constant and lurking threat of the relapse into our “old selves.” When this happens, overdoing gives way to distractions, where we abandon what we desire and try to forget about it.

Abhinav continually deployed strategies to reduce his work. Sometimes he tried suggestions he read about in books or followed recommendations from friends. He hired coaches, therapists, and other professionals to help with the change. He would throw all his energy behind the endeavor, hoping this would be the time when he would finally make the change. Yet when the strategies failed, he would be overcome by great disappointment and resignation, which led to giving up his efforts and doing other things to forget he gave up. He would continue his old work pattern and, when not working, distract himself with news, social media, or watching TV. But after a while, the unceasing pulse of his desire would activate, and he would start again, his efforts escalating. This rhythm of overdoing and distractions is well known to all of us who have tried to change our behavior, only to have run out of willpower when life’s stresses got in the way.

In the emotional realm, the long-unfulfilled desire can permeate our life. We would have either a specific fear of never reaching our goal or a broader sense of anxiety that would expand to encompass all other activities and goals. It’s difficult to relax and do enjoyable things if the looming unsatisfied want is always in the background. Even when Abhinav was spending time at home, playing with his kids, or making dinner with his wife, he was experiencing the background feeling of frustration. After all, he’d think to himself in those moments, if he could solve the problem of working too much, he could have many more enjoyable moments like this and change his life around. Many negative emotions show up when we feel stuck. There could be anger at ourselves and the world for being denied the one thing we want the most. A sense of hopelessness, dread, restlessness, and despair is common. After all, what’s the joy in living if the thing we desperately desire is never to be had?

These negative emotions are often fueled by our mind, which spins out beliefs or narratives about what past failures mean. Usually, these include the stories of something being wrong with us such that the fulfillment will always be unreachable; something wrong with other people, who can be seen as the direct obstacles or competitors for the desired thing; or something wrong with the world, which is seen as corrupt or organized in a way to never allow the achievement of the desired thing. Sometimes our mind produces unrealistic fantasies of what fulfillment of our desire would mean. Abhinav would fantasize about how completely transformed all aspects of his life would be if only he could work less.

An additional outcome of repeated failures would be the mind’s ruminative or obsessive thinking about how to gain our goal while increasingly doubting that it is possible. The obsession with the goal would permeate our life to the exclusion of other goals. It would also make it difficult to maintain peace of mind as we make some advances toward the goal. Are we going to lose it? Could it somehow turn out badly? And what is the chance that such success can continue? For example, when Abhinav’s attempts at working less worked well for more than a week, his mind would proceed to catastrophic possibilities—what if he declined a patient who would not be able to get care anywhere else and he inadvertently caused this hypothetical person further injury or even death? What if there was a catastrophic economic downturn so that his reduced work would financially devastate his family? Despite occasionally achieving (partially or temporarily) the object of our intense desire, the complete fulfillment and the inner freedom we hope to gain from it would remain elusive.

Another trick that our mind plays on us when we are experiencing action paralysis is to try to mask hopelessness and resignation with the appearance of genuine acceptance. Our inner voice, then, sounds something like this: “I’m fine without it. Maybe this way is better. I’m even better off without it.” Yet, despite these thin reassurances and the many distractions we may employ to stop thinking about what we want the most, giving up feels like an impossible option.

Finally, the body cannot but be drained by all the mental, emotional, and behavioral activity that keeps leading nowhere. It’s easy to forget that the stress of inner conflict is energetically expensive. If ruminative thinking about past failures and future fantasies continues for an extended period, the body under stress may start showing signs of illness (according to psychoneuroimmunology studies).1

The body does something else—which holds the key to why the whole Wheel of Self stops turning in the developmental way. In addition to being our active vehicle in the world, the body’s job is to hold our learnings in our nervous system and make them available to us as we face increasingly complex situations. The learnings don’t need to be conscious. Though sometimes implicit, these invisible beliefs are still active in our lives. When we are young, emotionally intense threats, losses, and rejections can be “overlearned.” Abhinav’s parents, who were immigrants, made many difficult sacrifices so that he and his brother could get the education they did. Abhinav’s early experiences affected how he thought of work and sacrifice in his own life, unconsciously pushing him to work more. Memories of his family’s struggles and his feelings of sadness, guilt, and fear were still vivid inside him.

Many of us carry such “active” memories in our bodies, whether of our early threats, embarrassments, loneliness, or rejection. Trauma researchers show how the body carries the continued threat of early situations and acts on the present circumstances as if they were the past.2 This, then, gives us a clue as to why the whole self-system—mind, emotions, body, motivation, and behavior—gets stalled. If the self were, in fact, in danger, it would be rational to hurry, worry, obsess, and get exhausted. The self-system acts rationally but mistakes the present for the past and, in doing so, renders itself ineffective. The stalled self-system is the self in a cloud of time distortion. If early overlearned experiences distort how the self interacts with our everyday reality, we are not acting in relation to what is before us but reacting to what is behind us.

Now we have a more detailed picture of what happens to the self when it stalls. Before we find out how to restart each part of the self, it’s important to reflect on what parts of our life need further development. This will help us personalize the learnings in Part II and apply them to the very thing we want the most. As we go along, throughout the book, we will follow Abhinav’s and others’ stories as they start moving their Wheels of Self again.

RED FLAGS OF STAGNATION

How do we know what aspect of our life would benefit from development? It would be something without which we feel our life would not be fulfilled, something we have been trying to gain repeatedly without success, something that makes us worried, frustrated, obsessed, frantic, hopeless, and finally, exhausted. We may spend many months ignoring it, yet it never really leaves the background of our consciousness. If this description doesn’t bring anything to your mind, here are four other cues that could alert you to your stalled “wheels.”

Behind schedule. Having strong wants frequently leads to a continual comparison with others. If we are unfulfilled in a particular domain (finances, relationships, fitness, creativity, etc.), we are likely to be inquisitive about other people’s achievements in that same domain. Often this leads to self-torment when we compare ourselves to those who have done better than us or glimmers of hope when we find people who were “late starters” like us but still managed to make it. This is the feeling of being “behind schedule,” missing a crucial opportunity, the feeling that “the ship has sailed,” or “what’s the point of starting now,” while at the same time being unable to stop wanting the very thing we are so “behind” in. We may feel other people have built better careers, families, bodies, friendships, or skills and that, by this age (no matter what that age may be), we should have achieved more or be more fulfilled in our life. Notice that this feeling of being “behind” is entirely age-independent, so 20-year-olds are as likely to suffer from it as 70-year-olds.

Envy. A related but different experience is envy. A person with an intense desire for something will frequently be around people for whom the thing that they want badly comes naturally and without any effort. For example, let’s say that no matter how much money we make, we find it difficult to get out of “the red”—but we know dozens of people who make less than we do, have an excellent standard of living, and are somehow always in “the black.” Even more maddeningly, we may know people who, once they decide they need more money, are showered with opportunities and cash. Or maybe we have been trying to have a meaningful relationship for years, and yet our love life is a series of relational shipwrecks, while our childhood friend has found the love of her life at 20 and is giddily happy 15 years into her marriage. Most people ascribe this to luck, “dumb” luck in particular, to highlight the undeserved nature of the riches showered upon their fortunate friends and acquaintances and to defend against the thought that luck may have nothing to do with it.

Although somewhat unpleasant to think about, wanting what other people have while at the same time being irritated that they have it can be a great clue that our development has stalled in that domain of our life. Envy implies more than comparing our life to that of another person or even wanting to have something similar. It means we wouldn’t mind seeing them fail, and if this were to happen, we may feel schadenfreude, taking some pleasure in the misfortunes of others. When envious, we may discuss information about unfortunate events in other people’s lives (a career failure, a divorce, or a loss of their investments in a dubious scheme) eagerly and with gusto. This makes sense psychologically: if we believe we can’t have what we badly want, it is comforting to know other people can’t have it either.

While most of us shrink away from awareness that we are envious, facing and hearing our envy can be a great boon to self-development. Envy highlights the parts of our life in which we feel unfulfilled and underdeveloped, and if we were to take its clue, we could begin the hard work of restarting our growth.

Advice that never works. You have probably at least once been in the shoes of either the giver or seeker of advice that doesn’t work. In one scenario, a person to whom something comes naturally gives (either unsolicited or solicited) advice to someone who desires that same thing intensely. Imagine a frugal person giving financial advice to a spendthrift. Despite goodwill and the best effort of all the parties involved, such advice leads nowhere. It is either not executed or is executed in a way that mysteriously doesn’t produce any of the outcomes that the advice giver was hoping to produce.

This makes sense since advice given with the best intentions by someone naturally good at something is then interpreted by the distorted lens of the person who is terrible at it. If we receive such advice while “stuck” in some part of our development, we may discard it for various seemingly logical but self-deceptive reasons, postpone its implementation until the “right” time, or follow it too literally or too vaguely for it to have any practical impact. Ultimately, both the advice giver and seeker will likely end up frustrated and disappointed. We may want to reflect on what advice we seek most, what is on our self-help or inspirational bookshelf, and what workshops we have spent the most money on—this reflection may guide us to know which domains in ourselves are still to be fulfilled.

Being immature. It’s one of the self’s mysteries how the development in one aspect of self may cease while the development in other domains of our lives continues naturally. This is how we may end up being a perfectly competent 53-year-old professional with great friends and finances who, when romantically rejected, behaves as a petulant 16-year-old and, when abandoned, withdraws as a scared 7-year-old. This fact, that adults occasionally behave as if they were chronologically younger or immature, is frequently pointed out when it happens to others. Yet when we notice an immature outburst in ourselves, we often give ourselves excuses—we were tired, upset, or it was someone else’s fault. Very few of us are willing to give the immature parts of ourselves a closer look. And for a good reason. These aspects of us, stuck on the way to development, represent the most painfully unmet wants that have been continually denied and sometimes temporarily abandoned. Yet in that very same place lies, of course, the greatest potential of fulfillment.

OUTER BLOCKS TO CHANGE

There is one more thing we need to consider before we begin our process of inner change. In our attempts to become more fulfilled, we may underestimate how our social world may react to our change. Other people are potent causal forces in our world, and this is seen clearly when our inner change causes disruptions and complications in social relationships.

When people enter relationships of any kind (and become colleagues, acquaintances, friends, lovers, partners), there is usually an implicit social contract that is drawn between them—and that is that both people will keep “being themselves.” That usually means that many values, emotional patterns, behaviors, and beliefs will stay recognizably similar over time. This stability people exhibit over time makes others believe that each of us has an unchanging personality. It makes us think we know others well.

Why is this kind of “knowing” important to us? Because it makes us believe that it will keep the other person predictable in relation to whatever social contract we have entered. There is comfort in knowing that Friend A will always help us move, Friend B will come over and comfort us when we are sad, and Friend C can be counted on only when having fun. What happens if Friend A suddenly says he has no time and Friend B starts asking unsettling questions rather than comforting us? We would think they are behaving “out of character.” If this behavior were to continue, we could decide that we don’t know who they are anymore, grow apart, or even end the relationship. Other people’s change is unsettling because it leaves us to the vulnerability that they may change in a way that does not suit us, for which we are not prepared, and that we do not like.

What would a healthy approach to others’ continuing development be? It would be like the attitude of healthy parents: they know their children are growing and take for granted that their relationship will have to continually change to be able to keep up with the child’s development. This is the case no matter how threatening these changes may be. As adults, we can do the same for each other—we can see our partner’s, friends’, and colleagues’ development as an exciting opportunity to learn to support, encourage, and adapt our relationships to that change, no matter how much we may like the comfort of the status quo.

Occasionally we may develop in ways that make it difficult to maintain our relationships in the ways we are accustomed to. A couple in which one person has discovered the joys of “living in the moment” while the other is concerned with long-term security may need to separate their financial accounts for the sake of relational peace. A partner of someone who has become a fitness buff and wants to spend a lot of time doing physical activities may have to spend more time alone or with friends. Developmental change challenges relationships.

The other option is to forfeit our own development, and that of the other person, so that we can keep the relationship in its original state. It’s like saying, “If you stay in your box, I’ll stay in mine.” So, as you decide whether to begin your own process of change, keep in mind that those around you may be startled, and even made uncomfortable, by your “new self.” Given that we know how challenging this can be, we can communicate every step of the way, to give the best chance to the evolving relationships.

Just as we prefer others to be predictable, we like to know who we are. Studies have shown that people seek out self-verifying information, engaging with others in a way that will confirm what they already believe to be true about themselves.3 This perception of permanent personality—unchanging stability in who we are—can be a serious obstacle to development. Who we believe we are is often an enemy of who we want to become. As humans, we are fond of categorizations—whether we are put into a box by a personality test, a horoscope, or a leadership questionnaire. Being told that we are an “introvert” or a “Pisces” or a “driver” may be thought-provoking as long as it doesn’t entrench us in a glass box that development is supposed to shatter. If we think of personality as early learned skills, then our development lies on the opposite pole of our trait “box.” If chronically extroverted, we may need to learn to be fulfilled in our own company; if too amiable, we may need to learn assertiveness; if too assertive, amiability.

Though we may like our “boxes,” or even prefer the status quo, the perception of there being no movement in self is illusory. Our potential will keep pulling us forward; if we prefer not to move, we have to exert force in the opposite direction. What looks like stability is a vibrating tension between our fears of change and developmental potential pulling in opposite directions. Despite its appearance, the status quo, when applied to personal development, is not static, not peaceful, and can rapidly yield to either fear or development, at any moment.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

You can use this book in two ways: (1) as a manual about what self is and how it develops and (2) as a guide to your own development.

If you focus on the first objective, the book may provide you insights into how different parts of the self operate, why self-development stalls, and what it would take to create sustained self-change. Ideally, you would also be able to parse better the widely varying psychological writings you are likely to see in scientific and pop literature. The hope is that you will gain enough insight and expertise to know what of the myriad psychological advice you are bombarded with daily is likely to work, under what conditions, and to what effect.

Another way to read this book is not just as a curious student of human nature but as someone who wants to make meaningful changes in your own life. If so, you can use this book to catalyze your natural growth. You can read it and do the exercises at your own pace. Please use them as guides to exploration, not as mandatory homework or a painful chore. You can experiment with the techniques, devise new ones based on the principles you learn, and do whatever you feel works for you while trying to catalyze your own developmental process. There are as many routes to development as there are people. It’s important you follow your own way.

Like all living things, the human organism has evolved to keep trying to develop as long as it lives. That means that even when the development slows or stalls, such as when we observe a plant not given enough sun or water, the developmental process doesn’t die away until the organism dies. As long as we are alive something in us will continually try to pull us forward and propel us to grow. Unlike plants or animals who are forced to react to their environment as they find it, we are fortunate to use our formidable consciousness to make the inner changes required to rearrange our outer lives for the benefit of our growth.

Learning about how the self works and how to facilitate its development takes time, energy, and the belief we have the inner wisdom that will help us fulfill parts of ourselves that have never or rarely experienced fulfillment. It’s possible, but it’s work. You may want to read the book but not do the work quite yet, and that is understandable. Change in some domain of self, even a positive one, changes your whole life, and only you can know when you are ready.