AILMENT ONE

Risk Blindness

“Risk blindness” is the condition of being unaware of the existence of risk. “Seeing is believing,” so when others mention risk, a risk-blind person or organization doesn’t understand what they are talking about. They believe that people who claim to see risk are delusional, shadow-boxing, and fighting imaginary foes.

A related condition, voluntary risk blindness, is suffered by those who deny the existence of risk even though they are fully aware of it. “There are none so blind as those who will not see”: Organizations or project teams that choose to wear a blindfold or risk blinders are deliberately acting as if they cannot see risk. This ailment has similar symptoms and treatment options to genuine risk blindness.

DIAGNOSIS/SYMPTOMS

When asked what they believe to be their biggest current risk, people suffering from risk blindness tend to reply “I don’t know”—which in effect is their biggest current risk! A senior Royal Navy admiral was notorious for asking everyone he met when he visited a ship: “What are your top three risks and what are you doing about them?” Any officer unable to answer was in trouble.

Every organization is exposed to risk, with a wide range of uncertainties arising both internally and externally. All projects are unique and complex undertakings that deliver change through people, operating within a series of constraints based on a set of assumptions and dependencies. Risk comes from a variety of sources, including technical, commercial, management, and external. To be blind to risk is to deny reality. There is simply no such thing as a zero-risk project or a risk-free organization.

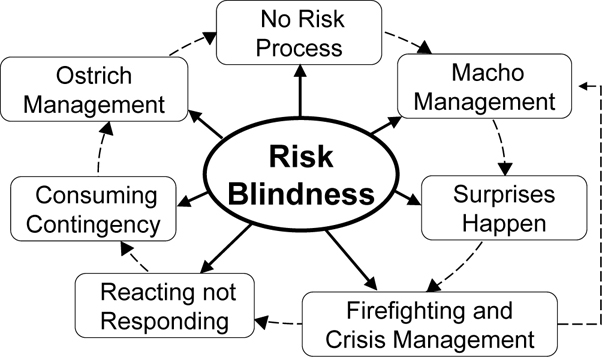

How can we know if our organization or project team is risk-blind? A number of diagnostic characteristics indicate risk blindness (see Figure 1-1). Each symptom is a direct result of the underlying condition, but they are also linked to each other in a self-reinforcing cycle. The symptoms produce an internally consistent and stable situation, making it particularly difficult for the risk-blind organization or project to recognize its own disability. However, the linked nature of risk blindness symptoms also offers an opportunity for treatment, since breaking the cycle in any one place can result in significant improvement.

FIGURE 1-1: Diagnostic Symptoms of Risk Blindness

No risk process

The first and most obvious symptom of risk blindness is that no risk process is in place. Why waste time on risk workshops or review meetings, why commit precious resources to risk management, if there is no risk to manage? If you ask to see a risk register, the risk-blind organization or project will tell you that they don’t have one because they don’t need it. A risk register records hypothetical things that could possibly go wrong in some imaginary future, whereas they are focusing on doing things right first time, every time in the present. They don’t have time to worry about things that will never happen.

Macho management

A macho management style sees the need for a risk process as a sign of weakness and an admission of the possibility of failure. True leaders don’t need to manage risk; they are warriors, not worriers. They pioneer and innovate, forging ahead toward the goal and overcoming anything that stands in their way. Anyone who points out the possibility of future risks is told to focus on the task at hand and stop worrying.

Those who identify risk might even be regarded as delusional, imagining things that will never happen. They might be characterized as “negative,” demotivating others and distracting them from today’s challenges by raising the spectre of an uncertain future. Worst of all is when these scaremongers ask for resources to be spent today to prevent or minimize possible problems tomorrow.

Surprises happen

The macho management aspect of risk blindness is bound to cause problems. The truth is that risk is out there, for every organization and all projects. In every field of human endeavor, wherever we are seeking to do something worth doing, there are uncertainties that matter—future events and circumstances that could have an effect on our ability to achieve our objectives. Denying the existence of risk doesn’t make it go away; it merely prevents us from seeing things sufficiently in advance to allow us to respond appropriately. Ignorance is no protection from the effects of risk. Risk-blind people, teams, and organizations are likely to encounter the unexpected—and to be surprised when they do.

Surprises will have two different types of effect, arising from the dual nature of risk as threat and opportunity:

• Threats that could have been avoided or minimized if they had been seen in advance will turn into problems or issues. Unnecessary delays and cost overruns will occur, waste and rework will increase, value and reputation will be degraded, and clients and customers will be disappointed.

• Potential benefits may be spotted too late to be captured or consolidated. A proactive risk process can identify opportunities in advance and allow them to be maximized and exploited. But a risk-blind organization or project will be unaware of these possibilities to work faster, smarter, or cheaper and will therefore miss the chance to save time, save money, improve productivity, enhance competitive advantage, and innovate.

Firefighting and crisis management

The inevitable result of a high number of surprises for the risk-blind organization or project is the need to deal with the effects of unforeseen risks. A classic symptom of risk blindness is a high level of firefighting, spending time and effort addressing the impacts of avoidable threats that turned into problems and recovering from missed opportunities that should have been captured. For projects, this can mean replanning, crashing the schedule, reallocating scarce resources, revising milestones, and adjusting stakeholder expectations. At the organizational level, this manifests as crisis management, with frequent emergency meetings of senior managers and executives trying to figure out how this unwelcome situation could have arisen and what they can do to limit the damage.

Reacting, not responding

The prevalence of firefighting produces a further diagnostic symptom that is common in the risk-blind: reacting rather than responding. Instead of taking time to consider the situation dispassionately, the organization or project is forced into dealing with it quickly, without sufficient time to think about it. Reaction relies on instinct and gut. Response, in contrast, takes longer and requires more careful thought. Because no risk process is in place to give early warning of possible risks ahead, little or no time is available to develop a considered response in advance of a threat’s turning into a problem or an opportunity passing by.

The firefighting macho management style thrives on the adrenaline-charged atmosphere of instant reaction, further reinforcing the negative cycle that is typical of risk blindness. Indeed, heroic firefighters can often achieve reasonable results when they are deployed in reactive mode after things go wrong. However, the urgent reaction will almost certainly not be the optimal way to deal with the situation and may make things worse by introducing avoidable secondary risks.

Consuming contingency

The organization or project that relies on its firefighters to rescue a difficult situation reactively will typically use contingency as its main way of mitigating the effects of threats that manifest as surprising problems or as a way of compensating for missed opportunities. The proactive response strategies of threat avoidance, transfer, or reduction can be implemented only in advance of the risk occurring, and they require prior awareness of the risk—which the risk-blind do not have. Similarly, proactive exploiting, sharing, or enhancing of opportunities is not possible if the opportunity is not seen in advance. A typical diagnostic symptom of risk blindness is reliance on contingency as a main risk strategy, with high levels of management reserve frequently called upon and possibly exhausted.

Ostrich management

The final characteristic of the risk blind is the tendency toward “ostrich management.” This term gets its name from the urban myth that ostriches bury their heads in the sand in the presence of danger until the threat has passed. The ostrich is supposed to react to a predator by “hiding,” on the principle that “If I can’t see you, then you can’t see me.” Ostrich management is used to describe a style of management that pretends risk doesn’t exist—and that believes that such pretense will result in the risk’s going away or failing to occur.

Ostrich management is an extreme form of risk acceptance, where risks are accepted by default without acknowledging their presence. This is different from true risk acceptance, of course, which is a considered and conscious recognition of the presence of risk that is either unmanageable or sufficiently low-level not to require proactive attention.

Head-burying ostriches are a myth, but any ostrich that tried to hide from a predator in this way would soon discover the futility of such a reaction and would probably not survive to tell the tale. In the same way, organizations and projects that deny the existence of risk in the unrealistic hope that doing so will somehow protect them from its effects are likely to suffer the unwelcome realization that ignorance offers no protection. Pretending a risk does not exist doesn’t make it go away; it just means that you take the risk with your eyes closed. The unseen risk remains invisible to the risk-blind until the fateful moment when the threat occurs or the opportunity is missed, when it is of course too late to do anything other than react blindly.

PROGNOSIS/EFFECTS

Being unable to see the risks we face has little or no influence on whether they occur. Indeed, if we see risks in advance, then at least we have a chance to deal with them proactively; not seeing them leaves us at their mercy. The risk-blind organization or project team should expect a number of specific outcomes as a result of this ailment, which are likely to become increasingly problematic if the condition is not treated effectively.

These effects of risk blindness at either the organizational or project level are clearly harmful, with direct impacts on bottom-line delivery and benefits. It is therefore essential that risk blindness be treated to restore a degree of risk sight that allows risks to be foreseen in time to respond to them appropriately.

Surprises

The most evident result of risk blindness is the increased frequency of surprises, as the organization or project constantly bumps into the unexpected. Most managers and leaders hate surprises because they lead to suboptimal, reactive decisions. The risk-blind are likely to encounter two types of surprises:

• A previously unforeseen threat suddenly manifests as an immediate problem

• An unidentified opportunity is seen too late to do anything about it.

Both of these situations can result in delays, cost overruns, performance shortfalls, damaged reputation, and customer dissatisfaction. Missed opportunities will cut the benefits and value delivered to stakeholders, reducing efficiency and making it harder to achieve objectives.

Deviation from plan

Surprises manifest in the risk-blind project as significant deviations from plan. Milestones or delivery dates will be missed due to “factors beyond our control” or “unforeseen circumstances.” Costs will rise as a result of situations that “no one could have predicted.” Where earned value management is practiced, the performance indices will routinely show trends toward increased estimates to completion.

Lack of control

At the organizational level, surprises will manifest as lack of management control, with strategic decisions being overtaken by events and a constant need to change direction. If the organization’s delivery structure includes portfolios of projects or programs, risk blindness will result in a need to reprioritize frequently. It could also lead to the cancellation of some components to rebalance the portfolio in response to emerging situations that had not been included in the original business case or strategic plan. The unexpected new knowledge may invalidate some strategic assumptions or previous decisions, requiring rework of the underlying decision analysis.

Low staff morale

Frequent surprises inevitably produce turbulence that will have a negative impact on staff. No one likes to work in an organization or on a project that seems to be out of control, where the situation is always changing in reaction to some unforeseen problem. Most people prefer stability and predictability at work, especially in settings such as projects where planning is valued. Risk blindness therefore often produces low staff morale, which can result in high turnover.

CASES

Cases of risk blindness abound—historically and in the present-day.

Sinking of the Titanic

Perhaps the most well-known example of risk blindness is the ill-fated RMS Titanic, which sank just over a century ago. The story of this ship has become synonymous with a disaster caused by refusal to recognize risk. The ship had some of the most advanced safety features available at the time and was widely believed to be unsinkable. In fact, the vice president of the Titanic’s parent company, Phillip Franklin, commented just hours after the Titanic had struck an iceberg: “The boat is unsinkable and nothing but inconvenience will be suffered by the passengers.” This blindness to the reality of risk led to the loss of 1,517 lives and the ship itself.

Global financial crisis of 2008

More recently, up until the middle of 2008, most major global financial institutions thought they had all risk covered through their use of asset-backed securities instruments such as collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and credit default swaps (CDS). As a result of these complex derivatives, they believed they were not exposed to risk. When liquidity and credit problems hit the financial sector, the entire structure began to collapse and their real risk exposure became evident.

The subsequent financial crisis has had much wider effects, largely as the result of the interaction of a number of underlying risky elements. Peter Tufano, executive board member of the Global Alliance of Risk Professionals, writing in Harvard Business Review in October 2009, said: “Many of the elements of the [2008–2009 financial] crisis were being talked about long before it happened … the sustainability of the subprime business … the U.S. current account deficit … obviously unsustainable household saving rates and debt levels … the imperfections of ratings models. What we didn’t see was how the elements were interacting. And that meant we were blind to the risk that the whole system would break down.”

Similar attitudes are adopted across organizations at all levels, where it is inconvenient or culturally unacceptable to admit that risk could affect the success of what is being done.

TREATMENT

Three treatment options are available to deal with risk blindness:

• Benchmarking to create awareness of what is currently not being seen

• Developing risk management capability

• Breaking the symptom cycle.

Often certain individuals in the organization or project team can see risks that others deny or ignore. These people are sometimes able to work with their colleagues to make them aware of risks, but more often they are discounted as negative-thinking whiners who worry too much. Where this is the case, external input will probably be required to provide the necessary sight. Project teams may seek advice from colleagues on other projects, perhaps those who experience more success. Outside consultants may also be useful to provide an objective perspective to a project or the wider organization, bringing insights from what they have witnessed elsewhere.

Benchmarking

The first requirement in treating risk blindness is for the sufferer to acknowledge the problem. It is necessary to confront the risk-blind with reality, to open their eyes and show them what they are missing so that they become aware of the world beyond their perception. This can be a painful process, and it therefore needs to be handled with care and sensitivity. Whether the message comes from internal colleagues or external consultants, one effective way to demonstrate the existence of risk is to benchmark the organization or its projects against others where risk is seen and managed proactively.

Benchmarking can take several forms:

• Comparing ourselves against recognized professional standards

• Determining how we measure up to our industry peers and competitors

• Evaluating how best-in-class organizations or projects in other sectors deal with risk.

The purpose of benchmarking is to demonstrate to the risk-blind organization or project team that risk is a universal constant, present in all projects and every industry. When risk is recognized and acknowledged, it can be addressed proactively, leading to more successful projects, greater achievement of organizational goals, higher delivered benefits and value to customers and stakeholders, enhanced reputation, and improved staff morale. As the risk-blind organization or project team learns what risks others see and how they deal with them, a degree of awareness will develop, with a dawning realization that they have been missing something important.

Developing risk management capability

Having realized that something is missing, the risk-blind can then embark on a course of remedial action. The goal is to create an effective capability to see risk and then manage it. There is a danger at this point of seeking a quick fix, usually in the form of risk training and risk software. While both are important elements of a risk management capability, they are by no means the full story.

Four areas will need to be addressed if risk is to be managed properly:

• Culture: the ethos and style of the organization, which need to be fully risk-aware

• Process: methods, tools, and techniques used for identifying, assessing, and managing risk, which need to be efficient, scaleable, and integrated with other business and project processes

• Experience: appropriate risk skills, knowledge, and competence for all staff, who should be empowered to manage risk, given the necessary responsibility and accountability, and focused on creating a learning organization

• Application: effective and consistent implementation of risk management at all levels in the organization, in an integrated approach that allows risk to be managed at the appropriate level.

Each of these areas requires attention, and an integrated risk management improvement initiative is often most effective to ensure that momentum is generated and maintained, and that benefits are captured and consolidated. This type of initiative is the main recommended treatment for risk blindness because it both addresses the root causes and provides a capability to deal with risk going forward.

This type of integrated risk management improvement initiative is a major undertaking that requires commitment from the organization. It will probably take some time before a fully effective organic risk management capability is created, so patience and persistence are essential. The truly risk-blind organization should start small, set achievable goals, celebrate and build on early successes, and ensure that momentum is maintained.

Breaking the symptom cycle

Treatment of risk blindness requires active intervention to address its symptoms, and their linked nature offers an opportunity to break the cycle at several points (as shown in Figure 1-1). The first symptom of “no risk process” will be dealt with by the main treatment option of the integrated risk management improvement initiative. The next three symptoms form a loop: A macho management style denies the existence of risk, so surprises occur that require a firefighting reaction, which in turn encourages further machismo. This vicious cycle can be tackled at any one of the nodes to bring about change, as follows:

• Macho management. Leadership training or coaching can expose an unhelpful management style and highlight its negative consequences. Macho management can be challenged and redirected. Personality profiling using one of the well-established frameworks can help individuals understand their default personal styles, along with associated strengths and weaknesses, and can make them aware of alternative approaches that might be more appropriate and productive.

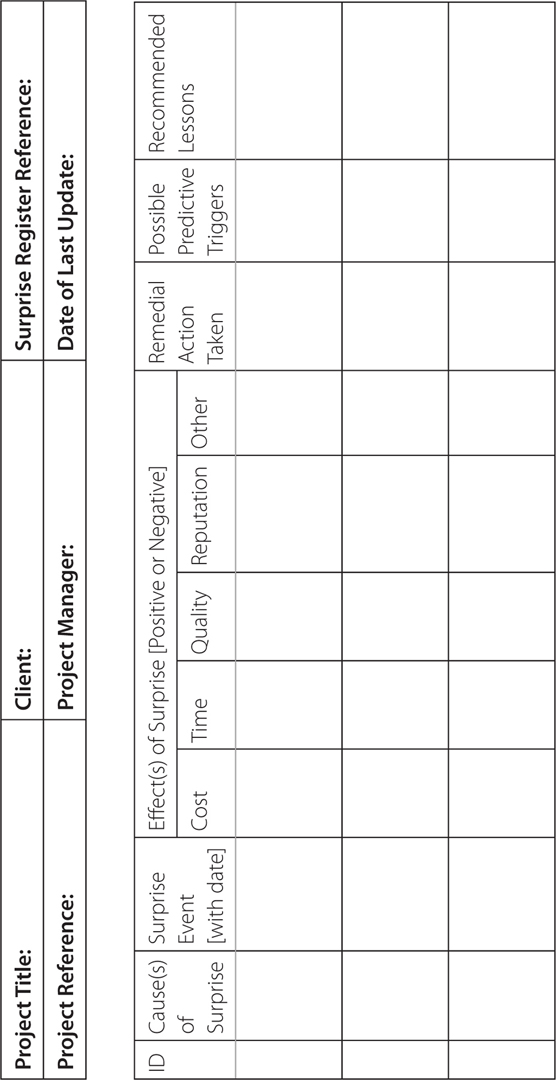

• Surprises. Documenting the occurrence and frequency of surprises and reporting them honestly at management meetings can be very revealing. Often risk blindness is accompanied by a related inability to identify repeated patterns of poor performance or bad news. Each unwelcome surprise is seen as “just bad luck,” a one-time incident that does not represent a trend. Analyzing the reasons for each surprise can expose root causes and underlying systemic weaknesses, and allow remedial action to be taken. A “surprise register” could be used to document each unexpected problem or missed benefit. (See Figure 1-2 for a sample format at the project level.)

• Firefighting and crisis management. Lessons-learned reviews can be helpful in indicating the degree of firefighting or crisis management occurring in the organization or its projects. These review meetings can encourage managers and team members to discuss recent performance and progress to date, highlighting areas for improvement as well as things that were done well.

Lessons-learned reviews should ideally be conducted on a regular basis. On projects, this means at the end of each phase of work or major milestone as well as upon project completion (as a “post-project review” meeting). For wider organizational learning, review meetings can be held in conjunction with the strategic planning cycle or after major decisions have been made. Where the review indicates firefighting as a common work mode, this should be taken as a warning sign that requires attention.

SURPRISE REGISTER

FIGURE 1-2: Sample Surprise Register for a Project

The remaining symptoms of risk blindness can be tackled in a similar way. The excessive use of contingency in strategic, operational, and project budgets can be measured using standard tools of cost control or earned value metrics. Leadership training or coaching can reveal cases of “ostrich management” in the same way that it highlights the macho management style, and lessons-learned reviews can indicate a reactive style of management alongside the tendency toward firefighting.

This treatment approach of tackling the various symptoms of risk blindness offers a range of possible interventions, each targeting one or more symptoms. The goal should be to break the cycle at its most vulnerable point. In some organizations the macho management style may be deeply embedded in the culture and hard to break. Or a project may have developed sophisticated firefighting techniques that work very well and that team members are reluctant to abandon. In each case, those seeking to treat risk blindness should look for the intervention likely to yield the greatest impact, tackling the symptom that appears most amenable to change.

Risk blindness is a serious ailment that can have a major negative impact on organizations and projects. Recovering from risk blindness is usually a gradual process; it is common for the risk-blind to gain risk sight incrementally. Early risk sight may be limited to perceiving only approximate outline shapes with a lack of detail. Over time, those recovering from risk blindness will gain more depth of perception, with the ability to see farther, more clearly, and in more detail. The journey from risk blindness to full risk sight will take time, and support may be needed from someone else who sees clearly and is able to guide, inform, and lead the recovering risk-blind until full risk sight is achieved. Organizations or project teams that want to avoid surprises and learn to become responsive rather than reactive will recognize the need for treatment and support until they can see clearly for themselves.