Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Thinking at the Speed of Bias

How to Shift Our Unconscious Filters

Sara Taylor (Author)

Publication date: 07/09/2024

Learn to recognize your unconscious bias and create positive change.

Respected DEI expert Sara Taylor presents a down-to-earth guide on how to tackle unconscious biases and foster true equity in our rapidly changing world. Through relatable examples and practical strategies, readers learn to deliberately slow down their thought processes and become aware of their filters in various situations. Taylor encourages readers to question their own assumptions by asking, "Do I know that what I'm thinking is actually true?" and "Why might I be reacting this way?"

The book demonstrates the importance of a clear set of competencies, skills, and strategies for addressing unconscious bias. By developing a culturally competent mindset and using a shared, holistic language to discuss these issues, readers gain the tools to understand, discuss, and implement change both at home and in the workplace. This approach avoids blame or shame, making it accessible and empowering for everyone.

The book's insights extend beyond individuals; it demonstrates how organizations can scale up cultural competence to transform their structures and systems. With a strong sense of hope, readers are empowered to make a difference, creating a more just and equitable world for all.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Learn to recognize your unconscious bias and create positive change.

Respected DEI expert Sara Taylor presents a down-to-earth guide on how to tackle unconscious biases and foster true equity in our rapidly changing world. Through relatable examples and practical strategies, readers learn to deliberately slow down their thought processes and become aware of their filters in various situations. Taylor encourages readers to question their own assumptions by asking, "Do I know that what I'm thinking is actually true?" and "Why might I be reacting this way?"

The book demonstrates the importance of a clear set of competencies, skills, and strategies for addressing unconscious bias. By developing a culturally competent mindset and using a shared, holistic language to discuss these issues, readers gain the tools to understand, discuss, and implement change both at home and in the workplace. This approach avoids blame or shame, making it accessible and empowering for everyone.

The book's insights extend beyond individuals; it demonstrates how organizations can scale up cultural competence to transform their structures and systems. With a strong sense of hope, readers are empowered to make a difference, creating a more just and equitable world for all.

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

SLOWING DOWN TO CATCH UP

Active Conscious

With cheetah-print leggings, a striped shirt, and matching gold necklace and bracelet that look more like tinsel garland than jewelry, her outfit might be considered gaudy if she weren’t a preschooler. With her hair pulled back in a loose braid, she sits with three fellow classmates at a table, each with a pool of green Play-Doh and a glorious selection of Play-Doh toys, from tiny rolling pins to various stamps and carvers resembling small pizza cutters, in front of them.1

Across from her sits another young girl with friends emblazoned in bold purple letters across the top of her T-shirt, fittingly appearing to be more concentrated on her friend to her left and what he is stamping into his Play-Doh pool.

In his hands is what appears to be an overturned model car that he’s working to envelop into the dough as he’s talking to the boy across the table from him. That last classmate, intent on the cutter he’s rolling across his dough as he sits in his Justice League T-shirt and khaki shorts, seems to be hyperfocusing all his attention on his creation, which still appears to be just a pool of dough.

With a full lifetime of learning and experiences ahead of them, one can imagine their potential and the many successes they can achieve, even as they are only concentrating on this immediate success of their Play-Doh creations awaiting to emerge.

What these four preschoolers don’t know is that separated from them by time and space is a group of preschool teachers along with a few preschool administrators taking part in a study. Pulled from an education conference they were attending, the study participants individually watched the preschoolers in a video of 12 randomized scenarios of traditional classroom activities—both free play and structured—of 30 seconds each.

Asked to “detect challenging behavior in the classroom . . . before it becomes problematic,” the eye movement of the teachers was then measured using eye-tracking software.2 In addition to the varying creations in front of them, the varying hairstyles and wardrobe choices, one of the most obvious differences among the four children was their race, as two were Black and two were White.

While the scenarios presented intentionally did not contain any challenging behavior, when the teachers were asked to anticipate it, where do you think the eyes of the teachers were focused?

On the Black students.

Who were the teachers? Both Black and White.

And remember who the students were. Preschoolers playing with Play-Doh.

What Were They Oblivious To?

Were the teachers in this study intentionally discriminating? Were they bad teachers? Maybe they just didn’t care about kids? Or am I trying to paint all teachers as bad?

The answer to all of the above is no. Like most of us, those teachers entered that setting with positive intent and were oblivious to their biased behavior. If you were to ask them, I bet they would say they wanted and did what was best for all their students, and they would sincerely feel, think, and say that . . . consciously.

But their conscious mind wasn’t the source of their actions.

It was their unconscious Filters.

If they were unaware of their biased behavior and are typical people like the rest of us, how likely is it that any one of us would have done the same thing and, like the teachers, been oblivious to it?

Very likely.

For all of us, across professions, racial groups, generations, and genders, our Filters are what we need to pay attention to, yet they are what many of us are oblivious to.

Active Conscious

Are Filters just unconscious bias?

No.

I coined the concept of Filters and Frames using concepts from the field of psychology, cultural competence, and unconscious bias. Our Frames are the objective differences we are more conscious of. Our Filters, on the other hand, operate in our unconscious and dictate our thoughts and behaviors without our knowing. While they are ubiquitous, they remain undetected to most of us.

Residing in our unconscious, our Filters are automatic mechanisms designed to take in and process exponentially more information—both biased and neutral—than we are consciously aware of. In any given situation, within milliseconds, they select from that stored information, bias and all, screening what gets passed to our conscious mind.

In doing so, they determine our thoughts, which in turn dictate our behaviors, all without our knowing. Regardless of whether that behavior leaves a positive or a negative impact, whether it creates connection or misunderstanding, or whether it produces disparity or equity, it originated with a Filter.

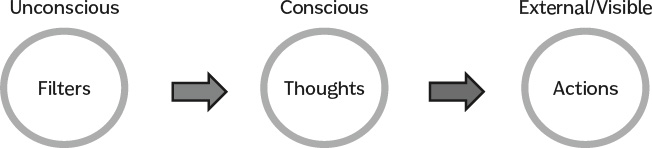

Think about each step in this automated process (see figure 1.1): our unconscious Filters shape our conscious thoughts, which in turn create our externally visible behaviors or actions. In any given interaction or situation, only one of these steps can be absent. Which one is it?

Figure 1.1 Passive Conscious

It’s the middle: conscious thought.

We skip that step of thought completely when we jump to an action without thinking about it, or in day-to-day rote tasks or common behaviors like greeting each other. Even if we don’t skip it, many times the conscious thought is very passive, rubber-stamping what our unconscious Filters have already decided.

The irony of this missed step is that it’s the most important step of all if we want to become more effective and make more equitable decisions. Instead of being passive or even absent, as it can often be, the conscious thought needs to be strong and active.

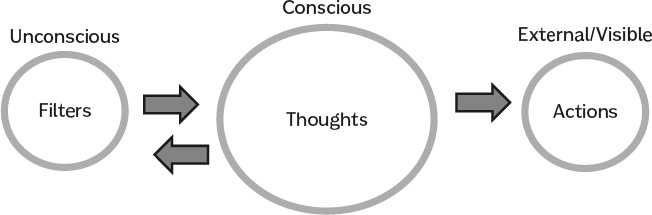

The Active Conscious is a process in which we intentionally slow down, pause, and question our Filters. Slowing down, counterintuitively, allows us to challenge this high-speed, automatic process and catch up to the speed of bias. Instead of allowing our Filters to determine our thoughts and behaviors, the Active Conscious process allows us to consciously check and challenge our Filters to determine our actions more actively (see figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Active Conscious Process

To efficiently take in, categorize, and prioritize millions of pieces of information in milliseconds, our Filters need to be automated. Yet because that automatic process doesn’t include a step to distill bias from our thoughts, we must take that step consciously in a more active process.

The Source of Our Behaviors

We are often caught by a false assumption that because our behaviors are easy to witness externally, they are what’s important. Just change the behavior, then everything will be fine—tell teachers to stop looking at the Black kids when they are looking for challenging behavior, and the problem is solved! What we miss is the oak tree–like roots of our Filters in which the behavior originates, and the fact that even when we sanction a specific behavior, those Filters remain.

Let’s remember, that behavior—the eye movement—that is external was created by a conscious thought, and that conscious thought was created by an unconscious Filter.

That means if I truly want to better understand others and the situations I am in, if I truly want to create equitable outcomes and even if I just selfishly want to be more effective for myself, I need to trace both my behavior and the behavior of others all the way back to the Filters that created them.

But the irony remains that the only often passive step is also the step that needs to be most active: the conscious thought.

We even have typical sayings that reflect this missed step. “I just wasn’t thinking!” or “How could I have thought that?” Consider the infrequent high-stress scenarios where a common person suddenly steps in to be the hero, pulling a stranger from a burning car or jumping in to help someone in distress. What do they often say? “No, I didn’t think about it. I just did it.”

Much more frequent are the numerous actions we take every day without thinking. These might be

- a rote behavior I perform regularly;

- an immediate response to someone I’m in conversation with that I later regret, wishing I would have thought about it more before blurting it out;

- a behavior driven by group norms, for example, if someone I am just meeting for the first time approaches me with hand outstretched, I do the same and reach out for a handshake without needing to think about it, which makes it likely that I’ll do the same thing whenever I greet someone else. And there are countless other examples.

Filters are powerful. And whether the thought is there or not, our behavior still stems from the Filter.

It’s about the Filters!

When we’re interacting with others, the source of what we observe externally is a Filter—their Filters.

Without the Active Conscious process, it’s not only that our Filters create our behavior; they also create perceptions and judgments about what we observe externally. I might first consciously notice someone’s skin color, or maybe someone else’s purple spiked hair or another’s significant limp. Those are their external, obvious differences, but how I perceive them, make sense of them, and judge them comes from my unconscious Filters. And if I can’t step into the Active Conscious process to challenge and shift those Filter judgments about external differences, it’s my Filters that continue to decide for me without my awareness.

Our Filters draw on a warehouse of our own past experiences. That’s why we believe them, even if they’re wrong. While our Filters are a part of us, the Active Conscious process allows us to separate from them, step to the side of them, if you will, to witness them, and, when necessary, create conscious thoughts that challenge them.

With the ability to check and challenge our Filters, we are less likely to create biased decisions or actions regardless of the differences—or similarities, for that matter—and more likely to create interactions with a positive impact that matches our positive intent.

Bring It Closer to Home

Like a joke that we already know the punch line to, it’s easy to look at a study like the one at the head of this chapter and, knowing it’s about bias, think, Well, that’s so obvious. I wouldn’t do that.

Because statistics say otherwise, I’d like you to imagine yourself in a specific situation, and we’ll use the Active Conscious process to better understand the judgments we might make.

You’re on a project team that you’ve been frustrated with, wanting to make a number of changes but never in the position to do so. Then you’re assigned as project lead, and so you spend several hours preparing for the first meeting with your colleagues, where you will outline the changes you want to implement.

The meeting is scheduled to start at 2:00, and you work in an organizational culture where everything starts on time, so you arrive at 1:50, ready to lead your colleagues in the agenda you’ve prepared. Your colleagues stream into the conference room one after another, but at 2:00, your colleague Alex has still not arrived. Even though your planned agenda starts at 2:00, you wait five minutes before starting, and it’s not until 2:15 that Alex finally arrives. Each of those 15 minutes you are getting more and more frustrated with their absence because they play a key role in the project.

What might be your thoughts about Alex? They

- are rude;

- don’t care about the project;

- showed up 15 minutes after the start time;

- are unprofessional;

- don’t respect you as the team leader;

- can’t be counted on.

Left unchallenged, these thoughts would likely shape your behavior toward this colleague. In the short term, perhaps you assign them lesser responsibilities. In the long term, perhaps you don’t give them an equitable role on the team, or perhaps, if the opportunity arises, you submit a negative review of them.

The Active Conscious Process

Let’s walk through the specific steps of the Active Conscious process:

- Stop to be conscious of our thoughts, even listing them out after the fact as we did with thoughts about Alex.

- Separate the thoughts that are subjective. Those are the thoughts that Explain and Evaluate, which is the telltale sign that they are coming from our Filters.

- Challenge the subjective thoughts coming from our Filters by focusing on what we are left with, the objective See or observe. Those are the thoughts that everyone, regardless of their Filters, would agree to. Almost always, those are few to none of the items on the list.

Of all the thoughts about Alex, only one is objective: showed up 15 minutes after the start time. The rest are subjective and shaped by our Filters, which means we don’t know whether they are true. In addition, our Filters add to misunderstandings if the individual has an observable difference in identity from us, perhaps a different skin color, generation, or perceived gender.

Particularly if that different identity is unfamiliar to us, or marginalized or frequently stereotyped, we are also more likely to attribute our negative Filter judgments to that entire identity group. For example, if they are generationally a millennial, our Filters might easily leap to generalizing the judgments to the whole group: Millennials can’t be counted on, and they’re so rude and unprofessional.

The Filter Shift Process

How do we know which of these thoughts were shaped by our Filters? We can SEE our Filters by examining the thoughts they shape. To SEE (See, Explain, Evaluate) is not about ocular vision but about being able to differentiate between our objective thoughts (See) and our subjective thoughts shaped by our Filters (Explain and Evaluate).

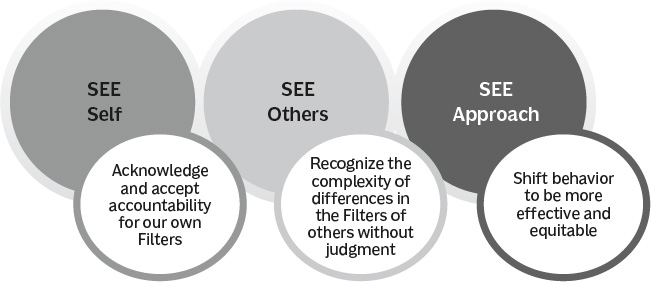

The Active Conscious process is the key, foundational strategy we continue to use throughout a three-stage developmental process to separate biased from neutral information about our self, others, and our behaviors. We first apply the Active Conscious process to acknowledge and accept accountability for our own Filters (SEE Self). We then use the process to assume difference in other people without judgment (SEE Others), and finally, we use the process to shift our behaviors to be more effective and equitable (SEE Approach).

This three-stage process of SEE Self, SEE Others, and SEE Approach is the Filter Shift process that I detail in my book, Filter Shift: How Effective People SEE the World (see figure 1.3). Filter Shift is both the ability to create more effective and equitable behaviors as well as the process of development we engage in to achieve that ability and thus move from unknowing to knowing and from ineffective to effective.

Figure 1.3 The Filter Shift Process

This is how we slow down to catch up to the speed of bias. The ability to recognize our Filters, take accountability for them and their impact on ourselves and others, and challenge and shift them is the necessary skill we must develop to both increase our own effectiveness as well as positively contribute to a broader environment of equity.

Unfortunately, most of us have yet to develop this ability, at best creating unintentional misunderstanding and at worst, creating harm to ourselves and others.3 That’s the bad news. The good news is that any of us can consciously develop it.

It’s Developmental

What makes this Filter Shift process so challenging is that it’s developmental. We’ll dive deeper into the developmental process in chapter 4.

Because it’s developmental, we can’t skip a step or jump back and forth. An infant doesn’t wake up one day with the developmental ability of a toddler and then regress to the developmental ability of an infant the next day. Likewise, they can’t decide they don’t want to be a “terrible two toddler,” skip that stage, and go straight to kindergartner.

This sounds like common sense, yet over and over again I hear both individuals and organizations, unaware that they haven’t developed through the first two stages of SEE Self and SEE Others, asking for a list of actions, which comes only in the third stage.

I call it the Nike syndrome because they believe they can just do it. They ask me: What should I do in this situation? What should I say? How do I respond? The answers to all those questions don’t become clear until we have developed through the first two stages and have developed the ability to identify the equitable actions or effective approach.

Focusing on actions too soon, we don’t realize that and how we might be ineffective.

We miss the true source, our Filters, and so we often miss the best approach.

Organizations also fall into the trap of focusing on doing, on completing tasks, on taking action before they have developed, also unaware that and how those actions might be ineffective. This is why so many organizations spin their wheels in DEI with tractionless transactions.

Individuals Remain Stuck in Clueless Oblivion

We learn about this developmental process of Filter Shift through the field of cultural competence. Unfortunately, we know that most of the population hasn’t developed the levels of competence that allow us to be effective as we interact across difference.4 Again, we’ll focus on that more in chapter 4.

On an individual level, most of us remain controlled by our Filters, oblivious to the reality that they’re creating our thoughts and driving our behaviors. This control by our Filters is compounded by the additional reality that many of us are also oblivious to the impact those behaviors have on others, regardless of our identity.5

Even when we have positive intent, because we believe we are more effective than we actually are, we don’t see the glaring need to develop.6 That leads us to create interactions that result in misunderstanding at best, biased decisions and microaggressions at worst.

What about those individuals who intentionally divide and discriminate? With increasing polarization felt across the globe, more of us feel this increase in divisiveness, created by the control of our Filters and a lack of development.

Getting together with family? Fewer of us are choosing to do so because of political polarization.7

Establishing close friendships with people of a different race? Most of us don’t.8

Experiencing hate-based incidents and violence? Twelve percent more of us are.9

Why? Of course, countless factors are involved, but in many cases of polarization, we can witness how an individual’s unconscious Filters control their thoughts and behaviors because they lack the ability to see, challenge, and shift them.

Let’s look at the example of the teachers again. Their attention was drawn to race or skin color. Yet consciously, I’m guessing they would have said, “I treat all the kids in my classroom the same, and I want what’s best for all of them regardless of race.”

Yet their eyes were on the Black kids.

Their Filters unknowingly misled them to believe that skin color was the important factor they needed to pay attention to. If they are like many individuals, they would have been oblivious to how their Filters attached a judgment to that specific Frame of skin color. All with the best of intentions.

The Path That Leads to Disparities

Unfortunately, it’s not only preschoolers or teachers or only the education system. It’s not only a rare phenomenon of disparities existing only in the United States, only among races.

Patterns of disparity are evidenced in all our systems and across many identities. That same evidence shows up on a more local level in organizations and groups. And, like the teachers in front of a video screen, the source of the disparities is rooted in each of us—more specifically, in our Filters. And the reality is that most of us, regardless of our identity, have not yet developed the ability to effectively shift them.10

Let’s follow the path leading from these teachers through the entire educational system.

Like the patterns of disparate response to Black and White preschoolers in this study, other studies have found similar patterns as students age through their educational experience.

One of these was conducted by researchers at Stanford who asked teachers with an average of 14 years of experience to review two incidents of minor classroom misbehavior. Those incidents were then randomly associated with a name that is stereotypically thought of as White (Greg or Jake) or a name stereotypically thought of as Black (Darnell or Deshawn). For the exact same issues, if the name associated was perceived as Black, the teachers found them more troublesome and, after the second offense, doled out more severe discipline, including suspension, than if the name of the student was perceived as White.11

If those preschoolers in the first study had been in a real classroom situation, or if the names in the second study were attached to real students, what would that mean for them, for their teachers, and for the relationship between them? What patterns of advantage and disadvantage would emerge for those students? And how would those patterns snowball throughout their lives?

Just as the Black preschoolers on the video screen were more likely to be seen as a source of challenging behavior, if you are a Black student in a real-life classroom, you are more likely to be disciplined with out-of-school suspension than your White counterparts. In a one-year span, 13.7 percent of Black students, 6.7 percent of Native/ Indigenous students, 4.5 percent of Hispanic students, and only 3.4 percent of White students were suspended.12

If a student isn’t in school, it’s all the more difficult for them to graduate. While the graduation rate for White students is 90 percent, it’s only 81 percent for Black students and even lower for Native and Indigenous students, at 75 percent.13

Let’s go back to the teachers. The behavior visible in the study was the teachers’ eye movement focused on the Black kids more than the White kids when observing the behaviors of those kids—judgments of behaviors created by thoughts, which were created by Filters. Those behaviors in real life would also likely lead to the Filtered behavior of suspending or expelling those same kids at a higher rate than others.

The pattern of higher suspension and expulsion rates for Black kids is the outcome that is visible on a broader level of individual schools or educational systems. When individual schools, administrators, and school systems with the best of intentions see those disparate outcomes, what do they do? They create across-the-board policies that restrict separation from the classroom for all students.14

If those schools and educational systems addressed the behavior and the outcome by applying an approach equal to all, why do they continue to spin their wheels, unable to gain traction to reduce educational disparities?

Because schools (a) focus on the wrong thing, missing the driver of those behaviors, which are the Filters, and (b) apply the one-size-fits-all, equality-based approach, assuming that will create equitable outcomes.

Of course, it’s not just schools or school systems. It’s a pattern repeated across all industries, professions, and societal systems.

The vital question we each need to ask ourselves is not if but when and where I am contributing to disparities in my profession, in my system, in my community?

Organizations and Systems Continue to Produce Inequities

As with education, our systems across the board churn out disparities. From health care to criminal justice to our economic systems, the inequities are clear across a wide variety of groups and identities.

At a more local level, organizations across all industries and sectors still rarely, if ever, achieve parity in representation, especially in leadership. Although White men make up only 35 percent of the population, their representation as Fortune 500 CEOs is more than two and a half times that at 90 percent.15 The first time a Fortune 500 company appointed a Black woman CEO wasn’t until 2009 (Ursula Burns at Xerox), and the first openly LGBTQ+ CEO wasn’t until two years later in 2011 (Tim Cook at Apple).16

What got us here? The obvious reason is centuries of intentional discrimination. The less obvious is millions of hiring, promoting, and managing decisions coming from the best of intent, yet driven by Filters of stereotypes, unknowingly left unchecked. As a hiring manager in one of our programs said, “I used to say I hired the best candidate, White, Black, or Purple. But it wasn’t until I developed the ability to Filter Shift that I realized I didn’t even know who the best candidate was.”

Environments of inclusion also remain elusive in most workplaces. Marginalized groups continue to express experiences in the workplace of being apart from versus a part of. That’s true for groups from transgender to Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), disabled, or women, and the list goes on.

Let’s stop to think about it. What decides how we feel at work and how we experience a workplace? Our Filters. So, if we want to be inclusive ourselves, we will need to be able to see and respond to the Filters of others. Yet few of us are able to do so. And all too many of us also operate in an organization with an equality-based culture applying the one-size-fits-all approach, oblivious to the Filters at play.

It’s not that organizations aren’t trying. But for decades DEI professionals have been hard at work initiating strategies, programs, and organizational change work with little to no tangible results, stuck in tractionless transactions and unable to transform their organizations. Unless we develop the individuals in our organizations and address the bias-laden Filters at play in our organizational structures, that transformation will remain ever elusive.

Beyond Individuals to Organizations and Systems

This same Filter Shift process that applies to individuals can subsequently be applied to organizations and eventually systems as well. When those organizations and systems show evidence of identity-based inequities, at their root are the Filters of stereotypes that were left unchecked and unshifted by a passive conscious.

Organizations and systems seeking greater equity can begin by first developing the individuals within them. Once those individuals have developed the ability to Filter Shift, they then can use the Active Conscious process to identify the Filter-based practices and policies they were previously oblivious to. This insight allows them to use the Equity Framework as described in chapter 11, which applies the steps of the Filter Shift process to organizations. A guided process with expanded questions, SEE Self focuses on the organization and its culture. SEE Others is focused on the stakeholders who are frequently marginalized or forgotten, and Shift Action encompasses the new, more equitable decisions, policies, and practices.

Reflection and Action

Start paying attention to your thoughts, particularly when you notice yourself making a judgment. Over the next few days, start building the muscle of the Active Conscious. As you observe the thoughts, challenge them using the SEE (See, Explain, Evaluate) model to separate the objective from the subjective thoughts. Pay attention to any patterns you might find. Those will likely help you identify your strongest Filters.