Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

U.S. Military Program Management

Lessons Learned and Best Practices

Gregory A. Garrett (Author) | Rene G. Rendon (Author)

Publication date: 12/01/2006

Introducing the only book on the market offering valuable best practices and lessons learned for U.S. military program management

The U.S. Department of Defense and the related defense industry together form the largest and most powerful government and business entity in the world, developing some of the most expensive and complex major systems ever created.

U. S. Military Program Management presents a detailed discussion, from a multi-functional view, of the ins and outs of U.S. military program management and offers recommendations for improving practices in the future. More than 15 leading experts present case studies, best practices, and lessons learned from the Army, Navy, and Air Force, from both the government and industry/contractor perspectives.

This book addresses the key competencies of effective U.S. military program management in six comprehensive sections:

• Requirements management

• Program leadership and teamwork

• Risk and financial management

• Supply chain management and logistics

• Contract management and procurement

• Special topics

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Introducing the only book on the market offering valuable best practices and lessons learned for U.S. military program management

The U.S. Department of Defense and the related defense industry together form the largest and most powerful government and business entity in the world, developing some of the most expensive and complex major systems ever created.

U. S. Military Program Management presents a detailed discussion, from a multi-functional view, of the ins and outs of U.S. military program management and offers recommendations for improving practices in the future. More than 15 leading experts present case studies, best practices, and lessons learned from the Army, Navy, and Air Force, from both the government and industry/contractor perspectives.

This book addresses the key competencies of effective U.S. military program management in six comprehensive sections:

• Requirements management

• Program leadership and teamwork

• Risk and financial management

• Supply chain management and logistics

• Contract management and procurement

• Special topics

CHAPTER

1

Toward Centralized Control of Defense Acquisition Programs: A Comparative Review of the Decision Framework from 1987 to 2003

By John T. Dillard

The issuance of Department of Defense (DoD) Directive 5000.11 and Instruction 5000.22 on May 12, 2003, marked the third significant revision of acquisition policy in as many years. Looking further back, these three revisions of regulatory guidance had evolved from two previous versions in 19913 and 1996.4 Each had its major thrusts and tenets and—perhaps of most importance to program managers—modifications to the Defense Systems Acquisition Management Process5 or Defense Acquisition Framework,6 which is the broad paradigm of phases and milestone reviews in the life of an acquisition program. The purpose of this author’s research was to examine the evolution of this framework and elucidate the explicit and implicit aspects of recent changes to the model to better understand its current form. Provided here is a synopsis of the most important findings. The full report of this research, examining both private industry and defense acquisition decision models, is available at http://www.nps.navy.mil/gsbpp/ACQN/

publications/FY03/AM-03-003.pdf.

The very latest DoD 5000 policy changes have come during a time of DoD transformation, which, while greater in scope than solely equipment and technology, is chiefly focused on changes to force structure and weapons employment capabilities. This latest version of the 5000 series was drafted in the documents rescinding its predecessor. In a memorandum signed October 30, 2002, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz said the series required revision “to create an acquisition policy environment that fosters efficiency, flexibility, creativity and innovation.”7 Interim guidance was issued, along with the recision, as a temporary replacement, outlining principles and policies to govern the operation of the new defense acquisition system. Among them:

3.1 Responsibility for acquisition of systems shall be decentralized to the maximum extent practicable. 3.18 The PM [program manager] shall be the single point of accountability for accomplishment of program objectives for total life-cycle systems management, including sustainment. 3.27 It shall be DoD policy to minimize reporting requirements.8

Though the 5000 series provides guidance for all levels, or acquisition categories (ACAT), of programs, its language is particularly applicable to the largest, ACAT ID, major defense acquisition programs (MDAP). In such cases, the milestone decision authority (MDA) is the defense acquisition executive, who also chairs the Defense Acquisition Board (DAB), a decision-making body for program milestone reviews. There is in fact both a component acquisition executive and program executive officer (PEO) in the hierarchy between them, and direct communication between the MDA and the PM is infrequent. Other top management stakeholders are Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) staff principals who sit in membership on the DAB, where milestone decision reviews are conducted. Communication between PM and OSD staff principals is more frequent, especially via the Overarching Integrated Product Team process.9 As of this writing, there are 36 MDAP (ACAT ID) programs in the DoD.

THE CHALLENGES OF DEFENSE PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Defense systems, known for their size and technological pursuits, are considered to be among the most challenging of projects. Owen C. Gadeken, building on previous studies at the Defense Systems Management College, concluded that the project manager competencies of systematic and innovative thinking were among the most needed and critical to accommodate growing complexities.10

The inherent difficulty of managing any program is exacerbated for the DoD by several additional factors, which have become even more prevalent in the last twenty years. Large defense systems are very complex, consisting of hardware and software, multiple suppliers, etc., and requiring design approaches that alleviate complexity by breaking down hierarchies into simpler subsets. Rapid technology changes, leading to obsolescence, have become particularly problematic for very large systems with acquisition life-cycles spanning a long period of time. Thus, it may not even be feasible to fully define the operational capabilities and functional characteristics of the entire system before beginning advanced development.11

The DoD 5000 series acknowledges these many complexities and difficulties facing MDAs and PMs in their management and oversight of large weapon system developments. An approach to mitigate these technological challenges, especially in the post-2000 series, is evolutionary acquisition, referred to by some outside of DoD as progressive acquisition. Also advocated by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), evolutionary acquisition has evolved worldwide as a concept over the past two decades. It is an incremental development approach, using iterative development cycles versus a single grand design. Described succinctly by the Western European Armaments Group, the progressive acquisition approach is:

a strategy to acquire a large and complex system, which is expected to change over its life-cycle. The final system is obtained by upgrades of system capability through a series of operational increments. (It) aims to minimize many of the risks associated with the length and size of the development, as well as requirements volatility and evolution of technology.12

DoD’s adaptation of this approach as evolutionary acquisition is a major policy thrust in the series, and it is the stated preferred approach toward all new system developments. This particular policy thrust is important to this study as it pertains to the framework of phases and decision reviews of a program moving toward completion. It is meant to change the way programs are structured and products delivered—separating projects into smaller, less ambitious increments. It is, additionally, one of several aspects of the new policy that affect the framework and its use as a management control mechanism.

ORGANIZATIONAL CONTROL THEORY AND DEFENSE ACQUISITION

Max Wideman also advocated progressive (evolutionary) acquisition and recognized senior management’s responsibility for financial accountability in private and public projects and their preference for central control. He noted problems with senior management control over complex developments, such as software enterprises like Defense Information Systems, even when projects were not very large or lengthy.13 His observations of large, complex programs align with classic contingency theory, which holds that organizational structures must change in response to the organization’s size and use of technology and as external environments become more complex and dynamic. Indeed, it has long been accepted that when faced with uncertainty (a situation with less information than is needed), the management response must be either to redesign the organization for the task at hand or to improve communication flows and processing.14

In his treatise Images of Organization, Gareth Morgan traces organizational theory through the past century and depicts organizations with a variety of images or metaphors. He warns that large, hierarchical, mechanistic organizational forms have difficulty adapting to change and are not designed for innovation.15 Further research by Burrell and Morgan indicates that any incongruence among management processes and the organization’s environment tends to reduce organizational efficiency and effectiveness.

His organizational development research, in accord with the conclusions of contingency theory, makes a strong case for consistency and compatibility among internal subsystems and changing external environmental circumstances.

In their book The Intelligent Organization, Gifford and Elizabeth Pinchot make an even stronger case for decentralized management in large, complex organizations faced with transformational change. They suggest that as organizations face increasing complexity, rapid change, distributed information, and new forms of competition, they must grow more intelligent to confront and defeat the diverse and simultaneous challenges. They posit that for an organization to be fully intelligent, it must use the intelligence of its members all the way down the hierarchy. They note that with distributed information there is distributed intelligence, and failure to render authority to those closest to the problem will yield lethargy, mediocre performance, or—worse—paralysis. Control will be maintained, and anarchy will not occur—but neither will success.17

What the cumulative research appears to support is that for large, complex hierarchies such as DoD, decentralized control and empowerment should be an organizational strength, given today’s environment of program complexity, evolving requirements, and rapidly changing technology.

AN EXAMINATION OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT LIFE-CYCLE MODELS

Models have long been used to illustrate the integration of functional efforts across the timeline of a project or program. The successful integration of these diverse elements is the very essence of project management. Models also help us to visualize the total scope of a project and see its division into phases and decision points. The interaction and overlapping of many and varied activities such as planning, engineering, test and evaluation, logistics, manufacturing, etc., must be adroitly managed for optimum attainment of project cost and schedule and technical performance outcomes. The Project Management Institute’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®) provides generally accepted knowledge and practices in the broad field of project management. Striving for commonality across diverse business areas and product commodities, it provides a generic framework as a structure for understanding the management of a project or program.

Project management difficulty climbs as system complexity and technological uncertainty increase, but is simplified by division of the effort into phases, with points between for management review and decision. The conclusion of a project phase is generally marked by a review of both key deliverables and project performance to (a) determine if the project should continue into its next phase and (b) detect and correct errors cost effectively. These phase-end reviews are often called phase exits, stage gates, control gates, or kill points.18 The institute acknowledges a variety of approaches to modeling project life-cycles, with some so detailed that they actually become management methodologies.

THE EVOLVING DEFENSE ACQUISITION FRAMEWORK

The 1996 Model

Models of program structure are important to DoD when communicating the overall acquisition strategy of a large acquisition project. The 1996 revision of the 5000 series was published after a rigorous effort to reform the defense acquisition system during the first half of the Clinton administration.

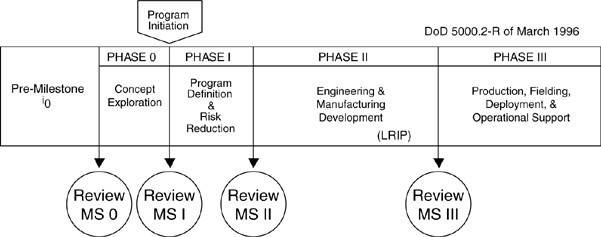

The 1996 model (Figure 1-1) is streamlined and simple and depicts only four phases and four decision reviews. Low-rate initial production (LRIP) could and frequently did occur before Milestone III in Phase II as a service secretary decision. Another key change from the 1991 model was the very deliberate move of the declaration of program initiation from Milestone 0 to Milestone I. Program initiation also serves as a benchmark of OSD interest in annually reporting to Congress, per 10 USC § 2220(b), the average time period between program initiation and initial operational capability (across all ACAT I programs of any commodity). In 1994, the average was 115 months.21

Figure 1-1. Defense systems acquisition management process.20

TOWARD CENTRALIZED CONTROL OF ACQUISITION PROGRAMS

The Current 2003 Model

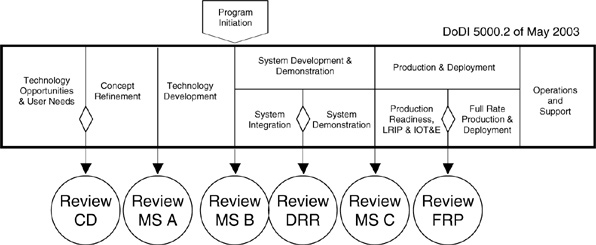

The current 2003 model (Figure 1-2) has five phases and six potential decision reviews. The most apparent, but perhaps least significant, change between the models is from numerical to alphabetical designation of major milestone reviews. Another obvious—and important—change is the appearance of divided phases and within-phase decision and progress reviews. With the latest release of the regulatory series, these additional subphases (or work efforts), along with pre-acquisition activities, have brought the total number of distinct activity intervals to eight, with as many as five phases and six decision reviews—more than at any time past. Each of these subphase efforts has its own entrance and exit criteria, making them more in practice like distinct phases of acquisition. All of the reviews are conducted at OSD level. Newest is the design readiness review, an evolution of the critical design review (which had heretofore been a PM-level technical review) in the previous interim model—and before that a mid-phase interim progress review. This model has several other significant implications, regarding placement of the milestones and activities, that this article does not address.23

Figure 1-2. Defense Acquisition Management Framework.22

The current policy describes reviews as decision points where decision makers can stop, extend, or modify the program, or grant permission to proceed to the next phase. Program reviews of any kind at the OSD level have a significant impact on program management offices. Much documentation must be prepared and many preparatory meetings conducted en route to the ultimate review. And while non-milestone reviews are generally considered to be easier to prepare for, a considerable amount of effort managing the decision process is still expended. For many years, six months have been allotted for OSD-level review preparation.24 It outlines the requirements for meetings and preparatory briefings to staff members and committees. Some representatives from program management offices keep an accounting of travel and labor costs associated with milestone reviews for an MDAP system. While only anecdotal data was available for this research, it is apparent that a substantial amount of program office funding is expended on items such as government agency or support contractor assistance, with supporting analyses and documentation, presentation materials, frequent travel to the Pentagon, and other associated expenses in preparation for high-level reviews.25

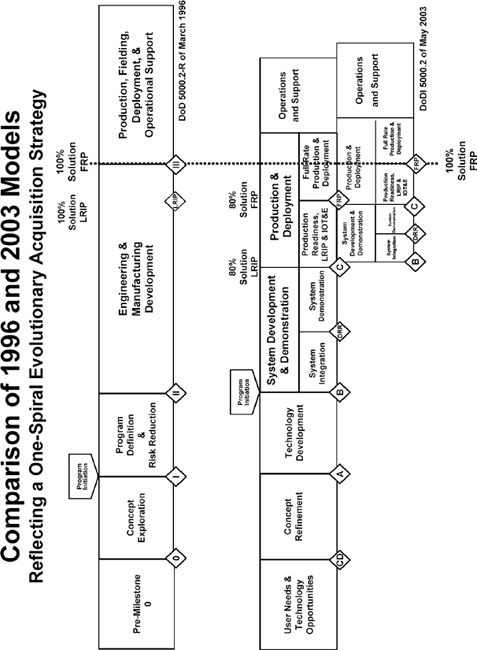

With evolutionary acquisition as the preferred strategy, the policy now describes notional systems as shorter developments (in system development and demonstration (SDD)) with iterative Milestone B-to-C cycles. The new DoDI 5000.2 prescribes, “In an evolutionary acquisition program, the development of each increment shall begin with a Milestone B, and production resulting from that increment shall begin with a Milestone C.”26 Thus, program managers can expect to undergo the management reviews determined appropriate not only for the initial increment of development in their program, but also the reviews specified for the follow-on increments. The strategy suggests the initiation of low-rate production of an 80% solution at Milestone C as the preferred approach. So a more accurate depiction of the new model, with perhaps only one “spiral” or increment of evolutionary effort, is shown below (Figure 1-3), presuming the achievement of 100% capability in the same timeframe as under the traditional single-step project strategy. The diamond icons represent decision reviews.

What becomes more apparent here is the increased number of actual decision reviews required, as well as the concurrent activities involved in managing a separate follow-on development increment and its requisite reviews. In fact, the most recent published guidance shows an example of a system with two increments of evolution having no less than fourteen reviews in its first eleven years from concept decision.27 Assuming that advanced development (SDD) for an 80% solution is indeed shortened, and further assuming that concept and early prototyping phases are no longer than before, the time and effort spent on control activities appears almost certainly to be disproportionate within the same 100% system capability delivery timeline. It seems in the least to be counter to the policy espousing decentralized responsibility, innovation, and flexibility at the program management level.

On the whole, the 2003 acquisition model prescribes a very new paradigm, and only time will tell us whether Deputy Secretary Wolfowitz’s goals of program management flexibility and innovation have been achieved. No major program has yet gone through the entire model, and none will for many years to come.

However, time spent “managing the bureaucracy” has long been an encumbrance to PMs. Back in 1988–89, military research fellows studying commercial practices at the Defense Systems Management College wrote about an imbalance of authority between PMs and the OSD staff.28 They recommended eleven improvements to the acquisition process, and the third on their list was “Reduce the number and level of program decision milestones.” In the context of the 1987 Life-Cycle Systems Management Model of five acquisition phases and five key decision points, they recommended that only one of these reviews be conducted at OSD level—the review for advanced development. They quoted the 1986 Packard Commission’s conclusions, which said, “He (the PM) should be fully committed to abide by the program’s specified baseline and, so long as he does so, the Defense and Service Acquisition Executives should support his program and permit him to manage it. This arrangement would provide much needed program stability.”29

As mentioned earlier, contingency theory encourages senior leaders to find the best fit for their organization’s structure to its environment, understanding that some situations might call for rigid bureaucratic structure while others might require a more flexible, organic one. The concept of control also is a cornerstone of cybernetics, or the study of organizations, communications, and control in complex systems. It focuses on looped feedback mechanisms, where the controller communicates the desired future state to the controlled, and the controlled communicates to the controller information with which to form perceptions for use in comparing states. The controller then communicates (directs) purposeful behavior.30

Figure 1-3. Comparison of 1996 and 2003 acquisition framework models.

The fundamental need for communication constrains the options for control, making the communications architecture a critically important feature of the control system. It is often heard that with communications in today’s information age warfare, we seek to “act within the enemy’s decision cycle.” For acquisition decision makers, the information architecture is the command and control hierarchy within our bureaucracy. And the decision cycle in the course of a program still, after many years, reflects 180 days of typical preparation lead time for a decision review. This Defense Acquisition Board decision cycle appears to be one very important process that has yet to undergo transformation.

Similarly, when the authors of New Challenges, New Tools for Defense Decisionmaking wrote about DoD decision making pertaining to training, equipping, manning, and operating the force, they suggested that decisions be based on senior leadership’s desired outcomes. They acknowledge that with a decentralized management style comes dilution of responsibility and accountability, unless vigilance of execution is maintained. But they agree with other theorists that while centralized decision making was consistent with the Cold War and well suited to the 1960s, it can be stifling and can restrict innovation.31

The Pinchots’ Intelligent Organization does not call for decentralization to undermine bureaucracy, but to improve it. The Pinchots advocate decentralization with horizontal interconnection (a network organization) between business units to lessen the reliance on going up the chain of command and down again for communication flow and decision. Rather than total autonomy for PMs, they support self-management, from trust, with responsibility and accountability.32 This thinking seems particularly appropriate to the information age and for a professionalized bureaucracy such as the DoD acquisition workforce, with disciplined standards of training, education, and experience steadily progressing since implementation of the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (DAWIA) in the early 1990s.

CONCLUSIONS

It is evident that the debate about centralized control and the number of OSD-level reviews has been taking place for a long time. The current model increases the number and levels of reviews, and their placement with regard to program events indicates that we are moving toward an even more centralized approach to control of acquisition programs. (A recent GAO report calls for even more departmental controls over acquisition than are now in place.33) But what is perhaps even more significant than this observation is that moving toward greater centralization of control at the higher levels may be a cause for serious concern, given predominant management theory cited herein. The mainstream of thought indicates that more efficiency and effectiveness might be gained from a different approach to an external environment of instability and uncertainty, whether from unclear threats and uncertain scenarios or from complexities of rapidly changing technology and systems acquisition.

Centralization of control is a management issue to be dealt with—the challenge is to avoid anarchy, with no guidelines or parameters, as well as excessive control. Might programs actually be lengthened by more cumbersome reviews? Whether fourteen reviews in eleven years are too many is a matter of conjecture and more debate. However, it is obvious that there are more reviews today than ever before, and these do have a requisite cost associated with their execution. We likely will continue the struggle to find the appropriate balance between centralized functions at OSD and autonomy for the management of programs in both explicit or implicit management policies and frameworks. Perhaps further areas of research can focus on the effectiveness of such reviews, and will almost certainly demand that the program costs of centralized decision reviews be measured. Another focus is the area of computational organizational theory, which singles out centralization as a project management model input variable that typically reduces risk but lengthens overall schedule. Moreover, a study of how DoD might exploit its current capacity through increased horizontal communication might provide insight toward how it can attain the decentralized empowerment it advocates.

Author’s Notes

The research presented in this chapter was supported by the Acquisition Chair of the Graduate School of Business & Public Policy at the Naval Postgraduate School. Copies of the Acquisition Sponsored Research Reports may be accessed from the web site www.acquisitionresearch.org.

Endnotes

1. USD(AT&L) Department of Defense Directive 5000.1, The Defense Acquisition System, May 12, 2003.

2. USD(AT&L) Department of Defense Instruction 5000.2, Operation of the Defense Acquisition System, May 12, 2003.

3. USD(A) Department of Defense Directive 5000.1, The Defense Acquisition System, February 23, 1991.

4. USD(A&T) Department of Defense Directive 5000.1, Defense Acquisition, March 15, 1996.

5. Defense Systems Acquisition Management Process, Defense Systems Management College, January 1997.

6. Defense Acquisition Framework, Defense Systems Management College, 2001.

7. Wolfowitz, Paul. Memorandum for Director, Washington Headquarters Services. Cancellation of DoD 5000 Defense Acquisition Policy Documents, October 30, 2002.

8. Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Defense Acquisition, Attachment 1, The Defense Acquisition System. October 30, 2002. (Interim Guidance 5000.1, p. 6).

9. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Acquisition and Technology), Washington, D.C. 20301-3000. DoD Integrated Product and Process Development Handbook, August 1998.

10. Gadeken, Owen C. “Project Managers as Leaders—Competencies of Top Performers.” RD&A, January–February 1997.

11. Pitette, Giles. “Progressive Acquisition and the RUP: Comparing and Combining Iterative Process for Acquisition and Software Development.” The Rational Edge, November 2001.

12. Western European Armaments Group WEAG TA-13 Acquisition Programme, Guidance On the Use of Progressive Acquisition, Version 2, November 2000.

13. Wideman, R. Max. “Progressive Acquisition and the RUP Part I: Defining the Problem and Common Terminology.” The Rational Edge, 2002.

14. Galbraith, J. R. Designing Complex Organization. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1973.

15. Morgan, Gareth. Images of Organization, Sage Publications, 1986.

16. Ibid.

17. Pinchot, Gifford, and Pinchot, Elizabeth. The End of Bureaucracy and the Rise of the Intelligent Organization. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1993.

18. Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 2000 Edition. Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, 2000.

19. Ibid.

20. Department of Defense 5000.2-R, Mandatory Procedures for Major Defense, Acquisition Programs and Major Automated Information Systems, 1996.

21. Ibid.

22. USD(AT&L) Department of Defense Instruction 5000.2, Operation of the Defense Acquisition System, May 12, 2003.

23. Dillard, John T. Centralized Control of Defense Acquisition Programs: A Comparative Review of the Framework from 1987–2003. NPS-AM-03-003, September 2003.

24. Defense Acquisition University. Program Managers Toolkit, 13th edition (Ver 1.0), June 2003.

25. Author’s unpublished interview with an anonymous representative from a major program office going through a milestone review, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California, February 19, 2003.

26. USD(AT&L) Department of Defense Instruction 5000.2, Operation of the Defense Acquisition System. May 12, 2003.

27. Defense Acquisition University. Program Managers Toolkit, 13th edition (Ver 1.0), June 2003.

28. Defense Systems Management College. Using Commercial Practices in DoD Acquisition. December 1989.

29. Packard Commission. A Quest for Excellence, Final Report to the President, 1986.

30. Ashby, W. R. An Introduction to Cybernetics, London: Chapman & Hall, 1960.

31. Johnson, Stuart, Libicki, Martin C., and Treverton, Gregory F. New Challenges, New Tools for Defense Decisionmaking. Rand, 2003.

32. Pinchot, Gifford, and Pinchot, Elizabeth. The End of Bureaucracy and the Rise of the Intelligent Organization. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1993.

33. GAO. “DOD’s Revised Policy Emphasizes Best Practices, But More Controls Are Needed,” GAO 04-53, November 2003.