Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Work Breakdown Structures for Projects, Programs, and Enterprises

Gregory T. Haugan (Author)

Publication date: 08/01/2008

The basic concept and use of the work breakdown structure (WBS) are fundamental in project management. In Work Breakdown Structures for Projects, Programs, and Enterprises, author Gregory T. Haugan, originator of the widely accepted 100 percent rule, offers an expanded understanding of the WBS concept, illustrating its principles and applications for planning programs as well as its use as an organizing framework at the enterprise level. Through specific examples, this book will help you understand how the WBS aids in the planning and management of all functional areas of project management.

With this valuable resource you will be able to:

• Tailor WBSs to your organization's unique requirements using provided checklists and principles

• Develop and use several types of WBS

• Use WBS software to gain a competitive edge

• Apply the 100 percent rule when developing a WBS for a project or program

• Establish a WBS for a major construction project using included templates

• Understand portfolio management and establish an enterprise-standard WBS

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

The basic concept and use of the work breakdown structure (WBS) are fundamental in project management. In Work Breakdown Structures for Projects, Programs, and Enterprises, author Gregory T. Haugan, originator of the widely accepted 100 percent rule, offers an expanded understanding of the WBS concept, illustrating its principles and applications for planning programs as well as its use as an organizing framework at the enterprise level. Through specific examples, this book will help you understand how the WBS aids in the planning and management of all functional areas of project management.

With this valuable resource you will be able to:

• Tailor WBSs to your organization's unique requirements using provided checklists and principles

• Develop and use several types of WBS

• Use WBS software to gain a competitive edge

• Apply the 100 percent rule when developing a WBS for a project or program

• Establish a WBS for a major construction project using included templates

• Understand portfolio management and establish an enterprise-standard WBS

Gregory T. Haugan, PhD, PMP, is vice president of GLH Incorporated, which specializes in project management consulting and training. He has more than 40 years of experience as a government sector official and a private sector consultant in the planning, scheduling, management, and operation of projects of all sizes and in the development and implementation of project management and information systems.

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to the Work Breakdown Structure

This chapter provides basic information about the work breakdown structure (WBS), including the background of the concept and its place and role in the project management process. Specifically, the chapter first discusses project management terms and definitions and explains why—on a very basic level—a work breakdown is needed. The chapter next illustrates where the WBS fits in the overall project management process and gives a history of the evolution of the WBS concept. Finally, the chapter briefly describes the role of the WBS in the private and public sectors.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT TERMS AND DEFINITIONS

Project management as a field of study has a set of acknowledged terms and definitions. The following segment presents key project management terms used frequently in this book. Although these terms are in common usage in the project management field, they are presented for reference and establish a terminology baseline.

KEY PROJECT MANAGEMENT TERMS

Activity: A defined unit of work performed during the course of a project that is described using a verb. An activity normally has a work description and an expected duration, an expected cost, and expected resource requirements. Activities and tasks are terms that are often used interchangeably.

Control account (CA): Formerly known as a cost account in earned value management systems, the control account identifies a specific WBS work element at the intersection of the WBS and the organizational breakdown structure (OBS), where functional responsibility for the work in a work package is assigned and actual direct labor, material, and other direct cost data can be collected.

Cross-cutting element: A WBS element that relates to work performed in other branches of the WBS. For example, the work performed in project management relates to other work in the project yet has its own unique identity.

Deliverable: Any tangible, verifiable product, service, or result that must be produced to complete a project or part of a project. The term is often used narrowly to refer to hardware or equipment, a facility, software, data, or other items that are subject to approval by the project sponsor or customer.

End items: A general term that represents the hardware, services, equipment, facilities, data, and so on that are deliverable to the customer or that constitute a commitment on the part of the project manager to the customer.

Organizational breakdown structure (OBS): A graphic representation of the work of a project in terms of organizational units.

Portfolio: A collection of related projects or programs and other work that groups projects or programs together in order to support effective management of the total work effort in a way that meets strategic business or organizational objectives.

Program: A long-term undertaking consisting of a group of related projects that are managed in a harmonized way. Programs often include an element of ongoing work or work related to the program deliverables.

Project: A temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.

Project element: A component of the work to be performed in a project derived from the logical decomposition of the total work (top down) or synthesis of a logical grouping of required activities or work elements (bottom up).

Responsibility assignment matrix (RAM): A graphic structure that correlates the work required by a WBS element to the organizational division that is responsible for the assigned task. A RAM is created by intersecting the WBS with the OBS. The control account is established at the intersection.

Risk breakdown structure (RBS): A hierarchical arrangement of the actual risks that have been identified in a project, or a hierarchical framework presenting possible sources of risk, either generic or project-specific.

Subproject: A logical major component of a project. A subproject is usually a WBS element that can be managed as a semi-independent element of the project and is the responsibility of one person or organization.

Task: A generic term for the defined unit of effort on a project; often used interchangeably with activity, but could be a further breakdown of an activity. A task, like an activity, has an action component and is defined using a verb.

Work breakdown structure (WBS): A product-oriented family tree or grouping of project elements that organizes and defines the total work scope of the project. Each descending level represents an increasingly detailed definition of the project work.

WBS dictionary: A document that describes in brief narrative format what work is performed in each WBS element.

WBS element: An entry in the WBS that can be at any level and is described by a noun or a noun and an adjective.

WBS level: The relative rank of a WBS element in a WBS hierarchy. Customarily the top rank, the total project, is level 1.

Work element: Same as WBS element.

Work package: The lowest-level element in each branch of the WBS. A work package provides a logical basis for defining activities or assigning responsibility to a specific person or organization. Also, the work required to complete a specific job or process such as a report, a design, a documentation requirement or portion thereof, a piece of hardware, or a service.1

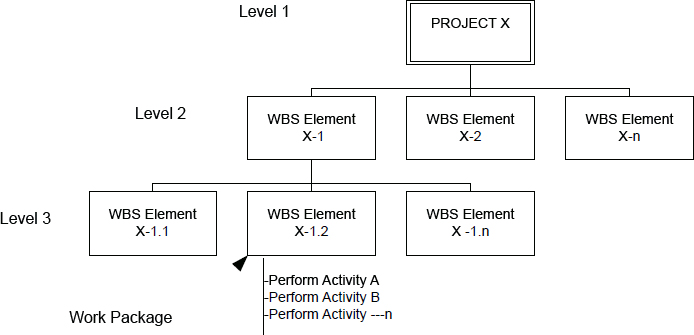

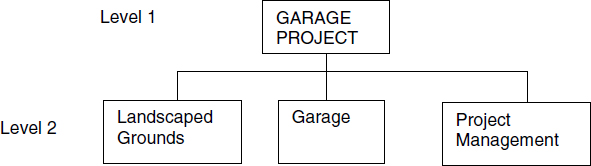

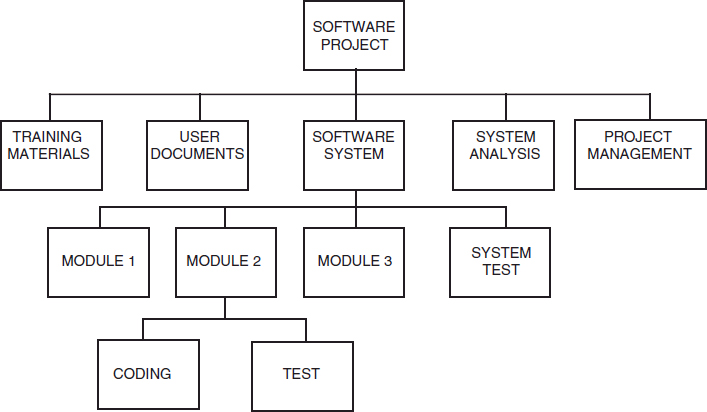

Selected terms are illustrated in Figure 1-1.

FIGURE 1-1 Generic Work Breakdown Structure to Level 3

THE PROJECT PROBLEM AND SOLUTION

Starting a new project is like starting to write a book—you have an idea of what you want to do but are not sure how to start. Many writers, like many project planners and managers, find that outlining is frequently the most effective way to start writing.2

An outline is both a method for organizing material as well as a plan for the book itself. But when you start outlining a book, especially a book based on research, you realize there are many ways to do it. In general, you need to plan your research or data gathering; decide what goes in each chapter, including appendices; and take into account drafting chapters, getting reviews, and the other steps involved in reviewing proofs and publishing the document. A sample outline for a book is included in the form of a WBS in Chapter 10.

A frequently used analogy for any large project is the old question, “How do you eat an elephant?” The answer is, “One bite at a time.” So the first step in preparing an outline or planning a project is to start defining and categorizing the “bites” (activities). The bites are important because they are where the useful work is accomplished. For a project, brainstorming can help define the bites from the bottom up, or a process of decomposition can be used, starting from the top, that subdivides the elephant into major sections working downward, as shown in Figure 1-2. In either approach, the objective is to develop a structure of the work that needs to be done for your project. This structure is the topic of this book.

FIGURE 1-2 Elephant Breakdown Structure—Top Level

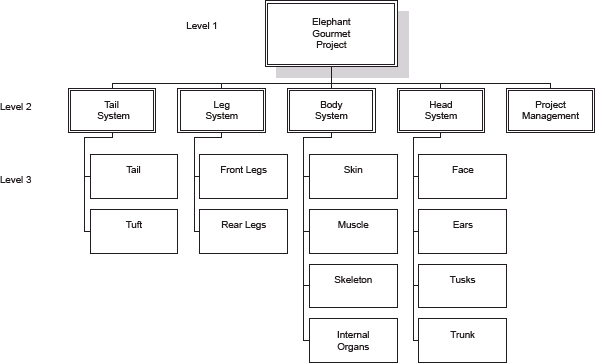

The parts of the elephant can clearly be broken down (or subdivided) further. For example, the head is made up of a face, ears, tusks, and trunk; the four legs could be individually identified; other body parts could also be identified, as could the tail and tuft. A WBS for a project follows the concept just shown. The WBS is an outline of the work; it is not the work itself. The work itself is the sum of the many activities that make up the project.

A WBS may be started either as an informal list of activities or in a very structured way, depending on the project and the constraints, and can end wherever the planner wants it to end. The goal is to have a useful framework that helps define and organize the work.

In developing an outline for a book, some things happen almost automatically, growing out of the discipline of the process. The first is that you limit the contents of the book. Preparing an outline forces you to define the topics, sections, chapters, and parts of the book. The same thing happens when you develop a WBS of the project. You consider assumptions and constraints often without focusing on them directly.

When you complete the outline of a book, you have also defined the scope of the book, especially when the outline is annotated. The same thing happens in a project. An annotated WBS becomes an initial scope description. This is logical and elementary: If the outline (WBS) addresses all the work, then all the items described in the outline delineate all the work or the scope of the project.

Developing the WBS is a four-step process:

Step 1. Specify the project objectives, focusing on the products, services, or results that are to be provided to the customer.

Step 2. Identify specifically the products, services, or results (deliverables or end items) to be provided to the customer to meet the project objectives.

Step 3. Identify other work that needs to be performed in the project, to make sure that 100 percent of the work is covered; identify work that (a) either cuts across deliverables or is common to the deliverables (cross-cutting elements), (b) represents intermediate outputs, or (c) complements the deliverables.

Step 4. Subdivide each of the work elements identified in the previous steps into successive logical subcategories until the complexity and dollar value of the elements become manageable units (work packages) for planning and control purposes.

A typical WBS is shown in Figure 1-3.

FIGURE 1-3 Typical WBS: Elephant Gourmet Project

In the early phases of a project, it may be feasible to develop only a two-to three-level WBS because the details of the work may not yet be defined. However, as the project progresses into the project definition phase or planning phase, the planning becomes more detailed. The subdivisions of the WBS can be developed to successively lower levels at that time.

The final subcategories or work packages created in step 4 are the bites that we are going to use to “eat the elephant one bite at a time”—that is, to perform the project work. The product of this subcategorization process is the completed WBS. This book provides more complete explanations of steps 2, 3, and 4 in later sections.

The following example demonstrates how to begin developing a WBS using the four-step process in a project to build a garage for a new car:

Step 1. Specify the project objectives: Build a one-car garage with landscaping on the existing lot; the garage should have internal and external lighting and plumbing.

Step 2. Identify specifically the products, services, or results (deliverables or end items): The garage and the landscaped grounds.

Step 3. Identify other work areas to make sure that 100 percent of the work is identified: A project management function is needed to do such things as construction planning, get permits, and award subcontracts.

The WBS so far would look like that shown in Figure 1-4.

FIGURE 1-4 Top-Level Garage WBS

Level 1 is the total project, and Level 2 is the subdivision into the final products (a garage and landscaped grounds) plus “cross-cutting” work elements (work elements whose products apply to several work elements) needed for the project, such as the project management function. The total scope, 100 percent of the project, is represented by the sum of the work in the three Level 2 elements.

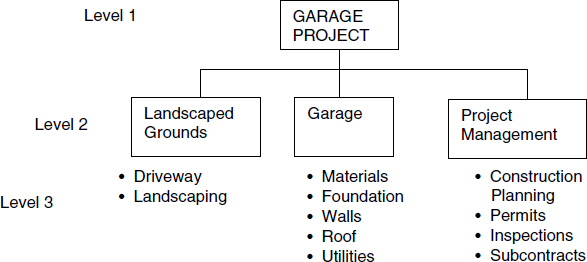

Step 4. Subdivide the elements until a level is achieved that is suitable for planning and control. The subdivision of each Level 2 element shown in Figure 1-4 is shown in Level 3 of Figure 1-5.

FIGURE 1-5 Garage WBS to Level 3

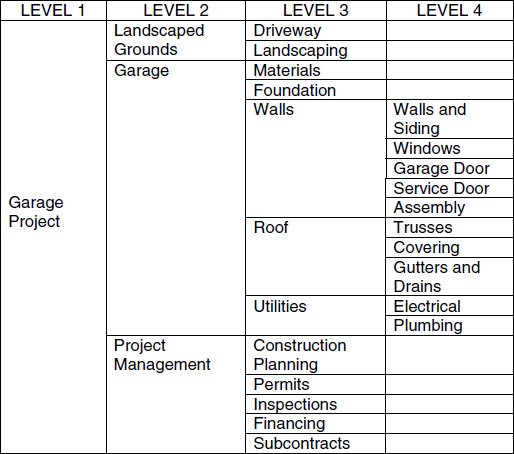

A further breakdown of some of the Level 3 elements could be performed. The complete WBS to the work package level (which is adequate for planning and control) is shown in Figure 1-6. The work package level is defined as the lowest level of each branch of the WBS; therefore, a work package may be at the overall Level 3 or 4 depending on the decomposition of the specific branch. The next level below the work packages is where the activities or tasks are performed.

In Figure 1-6, the WBS is presented in outline format rather than the space-consuming graphic format usually used. Either format is acceptable; this author prefers the graphic format, but the outline format is used when entering WBS data into project management software packages or to save space in documents.

FIGURE 1-6 Complete Garage Project WBS

The individual tasks or activities are located at the first level below the work packages and are not normally considered a part of the WBS. In fact, as discussed later, one of the primary purposes of the WBS is to provide a framework that helps you to define the activities of the project. When the WBS is complete, it covers the total scope of the project.

This mention of scope brings up a very important project management principle: Work not included in the WBS is outside the scope of the project. For example, in Figure 1-6, there is no heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system shown; therefore, an HVAC is not part of the project.

After the WBS is established, it must be maintained and updated to reflect changes in the project. The configuration and content of the WBS and the level of detail of the work packages vary from project to project depending upon several considerations, including the following:

Size and complexity of the project

Size and complexity of the project

Culture of the enterprise

Culture of the enterprise

Structure of the organizations involved

Structure of the organizations involved

Phase of the project

Phase of the project

Natural physical structure of the deliverable items

Natural physical structure of the deliverable items

Project manager’s judgment of work allocations to subcontractors

Project manager’s judgment of work allocations to subcontractors

Degree of uncertainty and risk involved

Degree of uncertainty and risk involved

Time available for planning

Time available for planning

The WBS is an excellent tool to use for communicating the scope of a project in an understandable form to the project team and other stakeholders. At the end of the planning phase, the plans and schedules are frozen or “baselined” and become the basis for executing the work of the project in stages. At the same time, the WBS is baselined and becomes one of the key mechanisms for change management. Proposed work that is not in the WBS needs to be added to the project and to the WBS through formal change control processes.

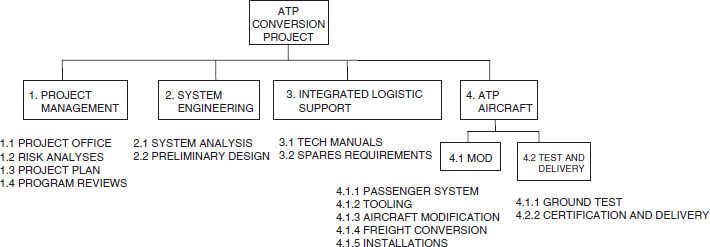

Figures 1-7 and 1-8 show additional sample WBSs that focus on the output products or deliverables of the project.

Figure 1-7 is a sample WBS for a civilian aircraft project in which a passenger aircraft is to be converted into a freighter. The output products are a certified airworthy converted aircraft, technical manuals, and a list of spare part requirements.

FIGURE 1-7 Sample WBS for an Aircraft Conversion Project

This WBS contains a cross-cutting work element labeled “System Engineering” that encompasses the work necessary to define the conversion. It is called cross-cutting because the work performed applies to all or most of the other WBS elements at the same WBS level; therefore, it cuts across other WBS elements. The WBS element “System Engineering” is present in all WBSs. “Project Management” is also a common cross-cutting WBS element.

Figure 1-8 presents a WBS for a software development project. The primary deliverable is the software itself, and secondary deliverables are the training materials and the user documents. The software system also has a cross-cutting work element labeled “System Analysis” that represents work such as project definition, workflow analyses, and structured analyses.

FIGURE 1-8 Sample WBS for a Software Project

The WBS can be used, in whole or in part, to make assignments, issue budgets, authorize work, provide the basis for other data organization schemes, and explain the scope and nature of a project. Projecting the WBS on a screen at a meeting greatly facilitates explanation of many aspects of the project and helps people who are newly assigned to the project to understand the major work elements.

Responsibilities are assigned at the lowest WBS level, such as “coding” and “test” in Figure 1-8. The WBS serves as a common focal point for presenting the totality of a project. Note that the WBS is not an organization chart, even though its hierarchical structure is similar to that of an organization chart.

THE WBS IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS

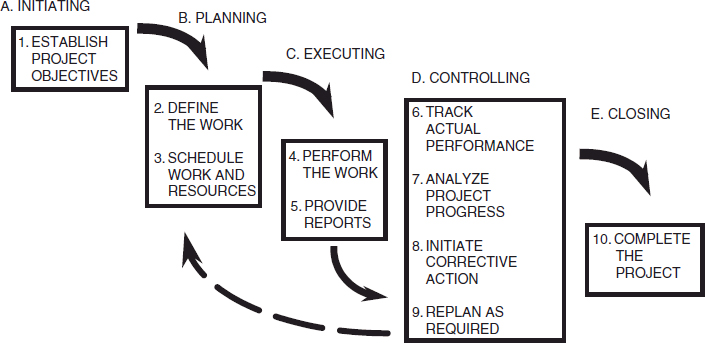

Managing projects is a continuous process. Figure 1-9 shows the 10 steps in the basic project management process. That process focuses on achieving the project objectives within the project management triad of time-cost-quality (performance) constraints and goals.

FIGURE 1-9 Basic Project Management Process

Each of the steps in the basic project management process has a specific output that is defined and documented. The steps are frequently iterative; circumstances that arise during specific steps may require revision of earlier steps and then repetition of all or part of the steps that follow the revised step. This constant iteration and replanning characterizes the dayto-day activities of the project manager and the project team.

Figure 1-9 shows the categorization of the basic project management process into five types of actions—initiation, planning, executing, controlling, and closing. The process of project management emphasizes the importance of planning before extensive project work begins and the importance of bringing the project to closure after all the work is done.

The WBS is the key tool in the planning phase, where the scope of work is defined, and at the completion of the planning phase, when the plan—including the WBS—is baselined. The WBS is omnipresent in virtually every aspect of managing the project. Therefore, it is very important to prepare the WBS early and correctly.

BACKGROUND OF THE WBS CONCEPT

The WBS is not a new concept in project management. This section provides some background that will assist in understanding the important role played by the WBS in managing projects effectively. This section also provides the basis for a later discussion of more complex aspects of the WBS.

Early U.S. Government Activities

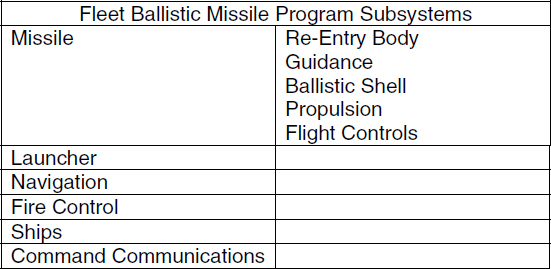

In 1959, Malcolm, Roseboom, Clark, and Fazar published a classic paper describing the successful implementation of a technique called Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT).3 Although the WBS is not addressed directly in the paper, the graphics include a breakdown (Figure 1-10) that shows how the concept for a WBS was evolving.

FIGURE 1-10 Early Polaris Project Work Subsystems

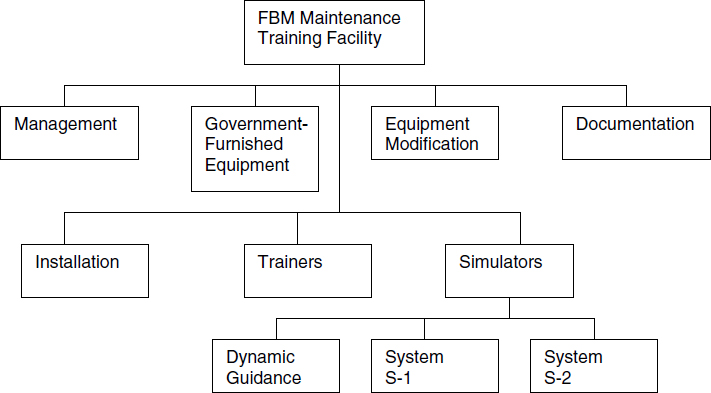

By 1961, the term work breakdown structure was in common use. At that time a sample WBS was included in an article published within General Electric Corporation that explained the importance of a WBS in developing effective management control systems.4 Part of this WBS for the Fleet Ballistic Missile Maintenance Training Facility is shown in Figure 1-11.

The PERT and WBS concepts spread widely and swiftly. These management tools and their application, as developed between 1958 and 1965, are the basis for much of the project management body of knowledge used today.

FIGURE 1-11 Work Breakdown Structure – 1961

The deliverables include equipment and equipment modification, documentation, trainers, and simulators. The WBS elements of management and installation are cross-cutting or support elements.

In June 1962, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), in cooperation with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the aerospace industry, published a document intended to guide the systems design of the PERT COST system.5 That document included an extensive description of the WBS that is essentially the same description used today.6

In October 1962, NASA published another document that expanded on its earlier discussion of the WBS.7 NASA stressed at that time that a top-down approach should be used in the development of the WBS to ensure that the total project was fully planned and that the derivative plans contributed directly to end objectives. It also stated that, in any integrated time/cost management system, both cost and time must be planned and controlled from a common framework.

Within the aerospace industry in the early 1960s, several companies were rapidly incorporating the concept of the WBS into their internal project planning operations. The author was using the WBS in his project planning in the Baltimore division, and the Orlando division of Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin) published a document that required the development of a WBS in its project planning when using PERT.8

In August 1964, the U.S. government published the PERT Implementation Manual, which included a discussion of the WBS.9 That document was intended for use by government agencies as well as private and public institutions. That document also recommended a top-down approach to developing the WBS so that “detailed plans will not be developed outside a common framework.”10 The authors stated that while it is apparent that plans, schedules, and network plans can be developed without a WBS, such plans and schedules are likely to be incomplete or inconsistent with project objectives and output products.

The development of a WBS in all the government and aerospace industry documents during this early period typically follows the same pattern. The planning begins at the highest level of the project with the identification of objectives and end items, and those are then broken down into logical elements.

When developing the WBS for large military systems such as those that existed in the 1960s, it became apparent that the top two or three levels were very similar for each family of systems; that is, the end items and the next level decomposition of the end items were the same. For example, all aircraft have wings, engines, a fuselage, empennage, landing gear, and so on, regardless of whether they are transports, fighters, or bombers. A typical WBS or template could be developed for major systems.

Since the time of its first use until the mid-1960s, many different concepts of the WBS existed. As a result, a project might be structured according to the contractor functional organization, contract phases, contract tasks, or other schemes. The DoD performed a special study in August 1965 to establish consistency among system acquisitions and to create a historical database. This effort resulted in the issuance of DoD Directive 5010.20, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, on July 31, 1968, which was followed by MIL-STD-881 on November 1, 1968.11 The DoD Directive sets forth the policy, and the military standard provides the guidance for implementing the policy. The latter document made application of the WBS mandatory for all DoD projects estimated to exceed $10 million that used research, development, test, and engineering (RDT&E) funds.

On April 25, 1975, MIL-STD-881A was published as an updated standard. The use of the standard was mandatory in three areas:12

(1) All defense materiel items (or major modifications) being established as an integral program element of the 5-year defense program plan;

(2) All defense materiel items (or major modifications) being established as a project within an aggregated program element where the project is estimated to exceed $10 million in RDT&E financing; and

(3) All production follow-on of (1) and (2).

In addition, the standard stated: “A work breakdown structure (WBS) may be employed in whole or in part for other defense materiel items at the discretion of the DoD component, or when directed by the Director of Defense Research and Engineering.”

MIL-STD-881B, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, was issued on March 25, 1993. This standard improved upon the previous edition in many areas, one of the most significant of which was the addition of an appendix containing a user guide.13 The required application was the same as MIL-STD-881A except that the dollar value minimum was eliminated. Furthermore, the standard stated: “This standard is to be used by both contractors and DoD components (Government activities) in the development of work breakdown structures for the acquisition of defense materiel items.”14

Recent U.S. Government Activities

In the mid-1990s, the role of 881B was modified by the Defense Standard Improvement Council, which reviewed the standard as one of many documents for possible cancellation, conversion, revision, or retention. The policy that evolved was that a program WBS was to be developed as outlined in 881B, and attention was directed to the user guide to avoid improper application. After a program WBS was developed properly by the DoD program manager, a solicitation needed to refer to 881B “for guidance only” as a basis for a contractor to develop a contract WBS. MIL-HDBK-881 updated and superseded the MIL-STD-881 documents on January 2, 1998.15

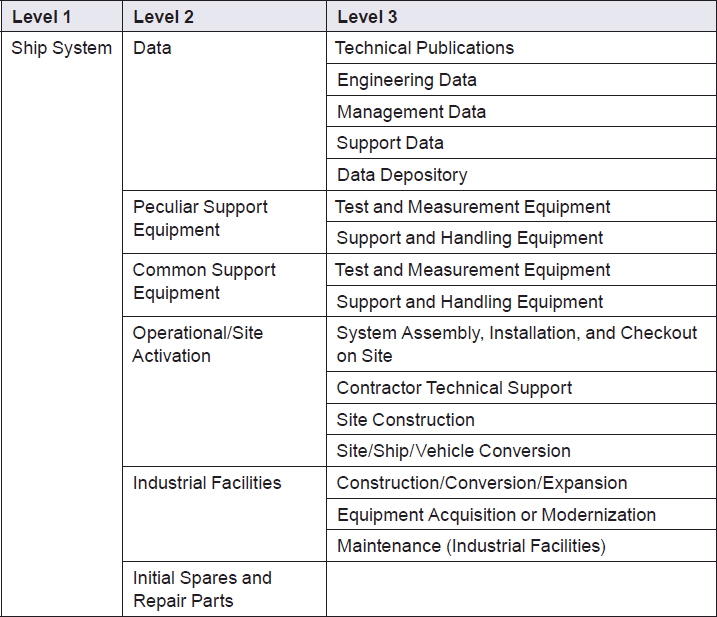

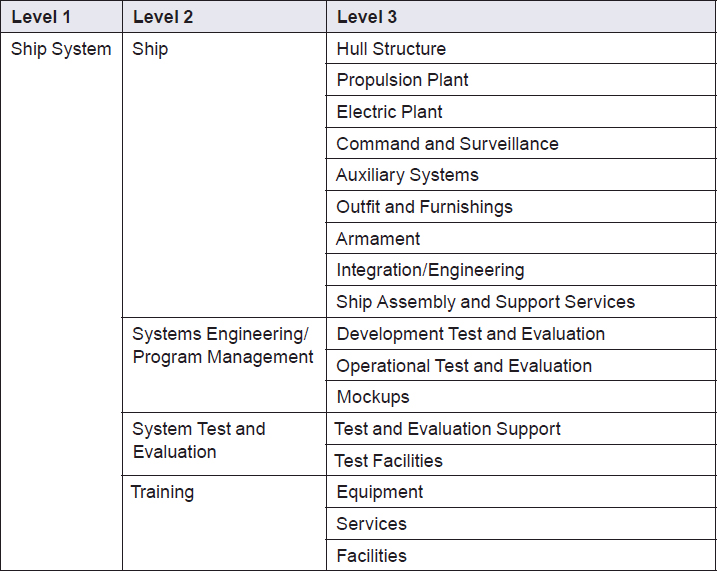

MIL-HDBK-881 is still directed at defense materiel items. The WBS templates for the same seven DoD systems that were in the original standard are still included in the handbook. The handbook includes the top three levels of the WBS and the associated descriptions (WBS dictionary) for the following systems:

1. Aircraft systems

2. Electronic/automated software systems

4. Ordnance systems

5. Ship systems

6. Space systems

7. Surface vehicle systems

Figure 1-12 presents the ship system WBS as included in the handbook.16

Because of a change in DoD philosophy, the NASA PERT and Companion Cost System Handbook was no longer mandatory and could not be cited as a contractual obligation. However, other DoD documents did specify the use of a WBS as a requirement.17

The DoD policy in 2002 was based on (1) the requirements of DoD 5000.2-R18 and (2) the guidelines of MIL-HDBK-881. The DoD 5000.2-R regulation states:

The PM shall consider the following topics during program design and comply with each, as appropriate. C5.3.1. Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). Systems engineering shall yield a program WBS. The PM shall prepare the WBS in accordance with the WBS guidance in MIL-HDBK-881 (reference (cj)). The WBS provides the framework for program and technical planning, cost estimating, resource allocation, performance measurement, technical assessment, and status reporting. The WBS shall include the WBS dictionary. The WBS shall define the system to be developed or produced. It shall display the system as a product-oriented family tree composed of hardware, software, services, data, and facilities. It shall relate the elements of work to each other and to the end product. The PM shall normally specify contract WBS elements only to level three for prime contractors and key subcontractors. Only low-level elements that address high-risk, high-value, or high-technical-interest areas of a program shall require detailed reporting below level three. The PM shall have only one WBS for each program.

The preceding paragraph refers to the work performed in the DoD project office.

MIL-HDBK-881A19 superseded MIL-HDBK-881 on July 30, 2005. It addressed mandatory procedures for those programs subject to DoD Regulation 5000.2. The Handbook also provides guidance to industry in developing contract WBSs.20

The Handbook presents guidelines for effectively preparing, understanding, and presenting a WBS. It is intended to provide the framework for DoD program managers to define their programs’ WBSs and also to be guidance to DoD contractors in their application and extension of the contract’s WBS. Section 1 defines and describes the WBS. Section 2 provides instructions on how to develop a Program WBS in the pre-award time frame. Section 3 offers guidance for developing and implementing a Contract WBS, and Section 4 examines the role of the WBS in the post-award time frame. The Handbook also provides WBS dictionary definitions for specific defense materiel items in its appendices.

The primary objective of the Handbook is to achieve a consistent application of the WBS for all programmatic needs (including Performance, Cost, Schedule, Risk, Budget, and Contractual). The discussion and guidance provided was based on many years of lessons learned in employing WBSs on DoD programs.

Further U.S. government requirements in the use of the WBS are included in Chapter 8 (Part II) of this book.

The Project Management Institute and the PMBOK® Guide

The lead in monitoring and documenting project management practices transitioned from the public to the private sector with the reductions in the space program, the end of the Cold War, and the rapid growth of the Project Management Institute (PMI).

The Role of the Project Management Institute

PMI, a professional association of approximately 300,000 members, through its conferences, chapter meetings, the monthly magazine PM Network®,21 and the quarterly Project Management Journal®,22 provides a forum for discussion of the growth and development of project management practices. In August 1987, PMI published the landmark document, The Project Management Body of Knowledge. That document was revised and republished in 1996 as A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (the PMBOK® Guide). It was updated again in 2000, and the third edition was published in 2004.23

The PMBOK® Guide reflects the experience gained in project management since the seminal work of DoD, NASA, other government organizations, and the aerospace industry in the 1960s.

The PMBOK® Guide

The PMBOK® Guide includes proven traditional practices that are widely applied, as well as information about innovative and advanced practices that have seen more limited use but are generally accepted.

The PMBOK® Guide is not intended to be a “how-to” document. Instead, it provides a structured overview of and a basic reference to the concepts of the profession of project management. The PMBOK® Guide focuses on the processes of project management.

The PMBOK® Guide is not as explicit with regard to the development of the WBS as the MIL-HDBK-881A and the other U.S. government documents referenced earlier are. There are some differences, as might be expected with 30 additional years of experience. The PMBOK® Guide addresses a broader audience than the DoD documents and includes all commercial applications. It also describes experience in the field since the 1960s.

In addition to the discussion of the WBS in the PMBOK® Guide, PMI has published Practice Standard for Work Breakdown Structures, which is intended to be more universal in application than the comparable DoD Handbook.24

The Practice Standard complements this book in same manner as the PMBOK® Guide complements other books on project management topics. The author recommends that the reader of this book acquire the most recent edition of Practice Standard for Work Breakdown Structures from PMI because the WBS discussion and samples in it are useful.

The PMBOK® Guide uses the same idea of decomposing project work into manageable packages that was used in the early government efforts, which is described in the PMBOK® Guide as “the subdivision of project deliverables into smaller, more manageable components until the work and deliverables are defined to the work package level. The work package level is the lowest level in the WBS, and is the point at which the cost and schedule for the work can be reliably estimated.”25

In addition to the standard PMBOK® Guide, there is a U.S. DoD version that was published in 2003,26 a government version published in 2006, and a construction version that is based on the 2000 PMBOK® Guide. These are all available at www.pmi.org.

THE WBS IN THE GOVERNMENT SECTOR VERSUS THE WBS IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR

In most respects, there is no difference in the use of the WBS on government and non-government projects, especially in large private-sector enterprises. The principles are the same, whether the projects are performed in-house or are outsourced. The use of contractor or subcontractor labor to complement or supplement existing labor requires the same skills and tools as are required when performing the work in-house, because the project manager must manage day-to-day work performance to achieve project objectives within the time, resource, and performance constraints.

The use of the WBS is essential when major government projects must be approved by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), or when the projects are to be contracted out and the government project manager must develop the work statement, specifications, schedule, budget, and so on, and also participate in the acquisitions process. In addition, with the OMB requirement for use of the earned value management systems (EVMS), it is essential that an effective WBS be developed as a basic framework for an EVMS. The government or large enterprise project manager frequently has two roles: The first is to plan and manage the work of the basic organization, and the second is to specify and manage the work of contractors or other organizations. Both roles require an effective WBS. We will see in Chapter 9 how the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) follows good business practices in its use of the WBS for planning and management of department work activities.

This introductory chapter has three principal purposes: The first is to present project management definitions and terms repeatedly used in this book; the second is to provide the basic rationale for using a WBS—it is the same concept as an outline of a paper or report; and the third purpose is to show briefly where a WBS fits in the process of managing a project.

The WBS is not a new concept; it has been around for years. This book, however, presents new uses for the WBS concept. The originators of the WBS are basically the same people who developed all the project management concepts in use today and who learned what worked and what didn’t by trial and error. In the late 1960s the author established the WBS as a requirement for bidders and winners of the contract for the airframe and engines of the U.S. Supersonic Transport Program.

The next chapter describes in detail the fundamentals of developing a WBS, which can be applied to any project, whether the deliverable is a product, service, or result.

NOTES

1. DoD and NASA Guide, PERT COST Systems Design (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense and National Aeronautics and Space Ad ministration, 1962).

2. Michael L. Keene, Effective Professional Writing (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1987), 32.

3. D. G. Malcolm, J. H. Roseboom, C. E. Clark, and W. Fazar, “Application of a Technique for Research and Development Program Evaluation,” Operations Research 7(5): 646–69.

4. Warren F. Munson, “A Controlled Experiment in PERTing Costs,” PO-LARIS PROJECTION, GE Ordnance Department, November 1961.

5. See note 1 above.

6. Ibid., 26–34.

7. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA PERT Handbook and Companion Cost System (Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1962).

8. PERT TIME, Document OR 3424, v. 1 (Orlando, FL: Martin Marietta, 1963), 2–3.

9. PERT Implementation Manual (Washington, D.C.: PERT Coordinating Group, 1964): VI.1–VI.5.

10. Ibid., VI.4.

11. Department of Defense, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, MIL-STD-881 (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 1968).

12. Department of Defense, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, MIL-STD-881A (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 1975), i.

13. Department of Defense, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, MIL-STD-881B (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 1993).

14. Ibid., 1.

15. Department of Defense, DoD Handbook: Work Breakdown Structures, MIL-HDBK-881 (Washington, D.C.: Department of De fense, 1998).

16. Department of Defense, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, MIL-STD-881 (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 1968).

17. Department of Defense, Mandatory Procedures for Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAPS) and Major Automated Informa tion System (MAIS) Acquisition Programs, DoD 5000.2-R (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2002).

18. Ibid.

19. Department of Defense, DoD Handbook: Work Breakdown Structures, MIL-HDBK-881A (Washington, D.C.: Department of De fense, 2005).

20. Ibid., Section 1, “General Informa tion.”

21. PM Network® is a registered trademark of the Project Management Insti-tute, Inc., in the United States and other countries.

22. Project Management Journal® is a registered trademark of the Project Management Institute, Inc., in the United States and other countries.

23. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 3rd ed. (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2004).

24. Project Management Institute, Practice Standard for Work Breakdown Structures, 2nd ed. (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2006).

25. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 3rd ed. (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2004), 114.

26. Defense Acquisition University, U.S. Department of Defense Extension to: A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 1st ed., v. 1.0 (Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Acquisition University Press, 2003).