Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Breaking the Trust Barrier

How Leaders Close the Gap for High Performance

JV Venable (Author)

Publication date: 05/09/2016

For former US Air Force Thunderbirds' commander and demonstration leader JV Venable, inspiring teamwork was literally a matter of life and death. On maneuvers like the one pictured on the cover, the distance between jets was just eighteen inches. Closing the gaps to sustain that kind of separation requires the highest levels of trust.

On the ground or in the air, from line supervisor to CEO, we all face the same challenge. Our job is to entice those we lead to close the gaps that slow the whole team down—gaps in commitment, loyalty, and trust. Every bit of closure requires your people to let go of biases and mental safeguards that hold them back. The process the Thunderbirds use to break that barrier and craft the highest levels of trust on a team with an annual turnover of 50 percent is nothing short of phenomenal. That process is packaged here with tips and compelling stories that will help you build the team of a lifetime.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

For former US Air Force Thunderbirds' commander and demonstration leader JV Venable, inspiring teamwork was literally a matter of life and death. On maneuvers like the one pictured on the cover, the distance between jets was just eighteen inches. Closing the gaps to sustain that kind of separation requires the highest levels of trust.

On the ground or in the air, from line supervisor to CEO, we all face the same challenge. Our job is to entice those we lead to close the gaps that slow the whole team down—gaps in commitment, loyalty, and trust. Every bit of closure requires your people to let go of biases and mental safeguards that hold them back. The process the Thunderbirds use to break that barrier and craft the highest levels of trust on a team with an annual turnover of 50 percent is nothing short of phenomenal. That process is packaged here with tips and compelling stories that will help you build the team of a lifetime.

Colonel JV Venable (USAF, Ret.) is a graduate of the USAF’s Fighter Weapons School (Top Gun). He is a cancer survivor who went on to command and lead the USAF Thunderbirds, as well as 1,100 American airmen flying 95 aircraft in combat. He currently serves as the vice president of a research and development company, as a senior research fellow for the Heritage Foundation, and on the board of directors for Mercy Medical Angels.

—Mark E. White, Principal, Global Consulting Chief Technology Officer, Deloitte Consulting, LLP

“JV does an amazing job of sharing powerful real-life examples that we can implement in our organizations. A fascinating read that delivers a message so powerful yet practical. This book should be required reading for all leaders looking to take their teams to new heights!”

—Bob Korzeniewski, Executive Vice President for Strategic Development, Verisign Inc., 2000-2007

“Even though this was written by the ‘competition,' I found Breaking the Trust Barrier to be a great read. JV delivers a powerful message in a way that will stay with you and your team for years to come. Drafting is not just a process for building and leading high-performance teams; it's a pathway to success.”

—Rob “Ice” Ffield, Blue Angels Flight Leader/Commanding Officer, 2001–2002, and President and CEO, CATSHOT Group, LLC

“Breaking the Trust Barrier is a leader's must-read! JV masterfully combines his Air Force experiences with thoughtful insights from commanding the world-famous Thunderbirds to create a road map for building real trust. He talks so honestly about commitment, loyalty, and trust that his message easily translates to any business or leadership environment. I honestly can't wait to apply much of what I have read with my own team.”

—Dennis M. Satyshur, Director of Golf Operations, Caves Valley Golf Club

“JV clearly articulates the key to his success leading multiple organizations and gives readers a glimpse of the challenge, excitement, and emotion of leading a high-performance jet demonstration team. I followed JV in command of the Thunderbirds and was able to build on the principles he established. Leaders at all levels will fi nd this book inspiring, practical, and helpful in accelerating their leadership skills.”

—Richard “Spad” McSpadden, Commander/Leader, USAF Thunderbirds, 2002–2004, and Senior Director, Hewlett Packard Enterprise

“Multiple commands and his stint as the lead pilot of the USAF Thunderbirds have given Colonel JV Venable powerful insights that he has captured in Breaking the Trust Barrier. His imagery will sear the themes of this book in your memory. His conception of trust is striking, memorable, and entirely new to the literature of leadership.”

—Dr. Charles Ping, President Emeritus, Ohio University

“Captivating stories within Breaking the Trust Barrier make the process you'll find inside absolutely indelible. This is an inspiring book and, if you're like me, you'll start putting JV's techniques to work the moment you set it down. Whether you're a senior executive or just getting your footing as a leader, this is a must-read!”

—Linda Chambliss, Vice President, Global Account Operations, STARTEK

Part I: Are There Gaps on Your Team?

1. Draft Your Team to Trust

Part II: Commitment

2. Close the Traction Gap

3. Close the Engagement Gap

4. Plow the Path

Part III: Loyalty

5. Close the Passion Gap

6. Close the Confidence Gap

7. Close the Respect Gap

Part IV. Trust

8. Close the Integrity Gap

9. Close the Principle Gap

10. Close the Empowerment Gap

CHAPTER 1

Draft Your Team to Trust

It was a gorgeous day in the middle of the Thunderbirds’ show season, and we were flying over some of the most breathtaking countryside I had ever seen. The radios were crisp, and from the moment we released brakes we were hitting all the marks in a compressed maneuver sequence we had been perfecting for months.

The four of us completed our reposition behind the crowd line and then stabilized for just a second. The moment we passed over those 40,000 people, I pulled the trigger on the next maneuver. The 4 G* pull that started our trail-to-diamond cloverloop stabilized, and just as we approached the vertical I called the three jets behind me to move from their trail position to our signature diamond.

At the start of training season, the distance between jets was the same as we had flown throughout our operational lives, but now the formations were so tight—and the gaps between us so small—that I thought I could feel a shift as the left and right wingmen moved into position. So far as I knew, the surge that came with Rick “Chase” Boutwell and Jon “Skid” Greene moving into their respective formations was emotional, but it felt like they were literally lifting the wings of my jet.

As each accelerated into position that day, a very subtle shift took hold of our trajectory. The pressure came on as if a giant hand were pushing up on my left wing. The ensuing right turn began to take us away from a pure vertical loop, and, almost unconsciously, I countered with the call for “a little left turn” and the slightest amount of pressure on the stick to bring us back on plumb.

From the crowd’s perspective, this would be one of the best demonstrations of the year, and most spectators would leave with a level of pride that matched the wave of exhilaration we were riding as the last jet touched down. And yet the blemish of that trail-to-diamond cloverloop was still lingering in the back of my mind. I knew I hadn’t consciously turned the flight, but I was at a loss as to how the maneuver had gone wrong. After I watched the video recording of our demonstration in the debrief, I noticed a small difference.

My left wingman was more aggressive on his move forward, and he tucked into position a bit more quickly and closely than the jet on my right—and he stayed there. He was so close that he caused my left wing to become more efficient, to produce more lift than my right wing. Efficiencies—it was aerodynamic efficiencies! It wasn’t just a feeling that I was being carried by the team around me; the surge brought on from their proximity was real. That thought would change the way I looked at everything: we were drafting.

The Phenomenon of Drafting

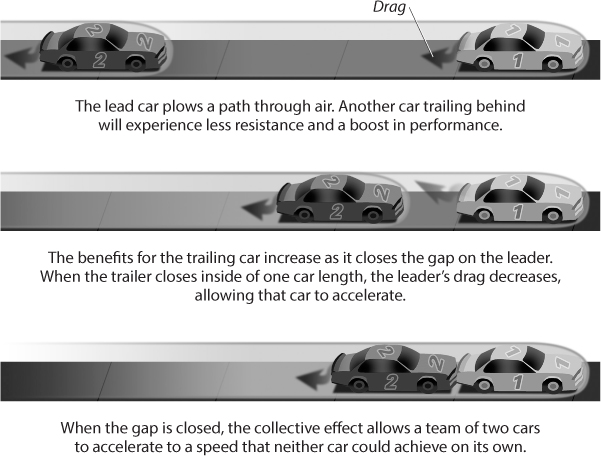

The aerodynamic phenomenon of drafting was discovered in the late 1950s by stock car racers who figured out that two cars running close together, nose-to-tail, could sustain a faster speed than either car could achieve on its own. Over time they figured out the cause of the effect: the lead car was taking on the wall of air for both, while the trailer was close enough to the leader’s bumper to relieve it from the drag it created as it moved down the track (see Aerodynamic Drafting).

Aerodynamic Drafting: Closing the Gap Benefits Both Team Members

While the effects are mutually beneficial, they are a little lopsided—at least at first. When a car speeds down the track, its movement plows a path through the air to create a vacuum of sorts that can help pull a trail car forward when it is still several car lengths behind the leader. And if the trailer elects to close on the leader’s bumper, the pull becomes more significant with every foot of closure on the leader’s car.

But, funny enough, the leader gains no relief from its drag until the trailer is within a single car length. As the trail car closes inside that distance, the leader’s drag begins to transfer from its bumper to that of the trailer. When the gap closes, the collective effect allows the team of two cars to accelerate to a speed that neither car could achieve on its own. It is closing the distance—the gaps between elements on a team—that makes drafting work. The more I thought about it, the more I could see drafting’s effects on the Thunderbirds everywhere I turned.

Every unit within our organization, from accounting and finance to maintenance and public affairs—literally every shop—was minimally staffed, and each relied on the others to help it execute its role. Those amazing people were lined up, bumper to bumper, taking the weight—the drag—off the individual or element in front of them while they sustained the draft for those behind them.

Drafting, in teamwork, is a phenomenon that replicates the aerodynamic benefits of bodies moving closely together. It requires leaders to inspire closure between individuals and entities to deliver cohesion, unity of effort, and team acceleration.

(aerodynamics) The phenomenon whereby two objects moving close together sustain a faster speed than either object could achieve on its own. (teamwork) The phenomenon inspired by the aerodynamic property of bodies moving closely together; it requires leaders to inspire closure between individuals and entities to deliver cohesion, unity of effort, and team acceleration.

Think about that in terms of you and your team. How many folks are snuggled up against your bumper, taking the drag off your efforts, and how many are sitting two car lengths back, smoking a Lucky while basking in the warmth of your draft? It is absolutely up to the folks in your wake to close the distance—you cannot make them close. It is up to us as leaders to set the conditions that will make them want to close the gaps. By incrementally building mutual commitment, then loyalty, and finally the kind of trust that will further the momentum of the whole team, we maximize the effects of drafting.

Closing the Gaps with Commitment, Loyalty, and Trust

Trust comes through a series of methodical actions that begin and end with the leader. No pilot begins the first day of his tour with the Thunderbirds flying inches away from another’s wing. That kind of proximity relies on trust that is built over time. Closing those gaps must be done incrementally, through a methodical process that, more than any other facet, relies on you.

Before we go into the process of building trust, let’s clear up one possible misconception right up front: the Thunderbirds are not all that different from your team. Certainly, some aspects of our mission made us unique, so let’s get them out of the way now.

Differences from Team to Team

The Thunderbirds’ flight-training program taught pilots who had never flown formation aerobatics everything from basic formations to the entire jet demonstration sequence. We started in mid-November, flying two jets, side by side, executing one maneuver over and over, 1 mile above the desert floor, with 3 feet of separation between jets. As the training progressed, we would methodically add jets and maneuver elements, lower the maneuvering floor until we had all six F-16 fighters flying maneuvers 400 feet above the ground. By the end of the training season, the gaps between aircraft were as small as 18 inches.

In mid-March the team packed up and went on the road for the next eight months to fly airshows all over the world. With the deployments, practices, airshows, and redeployments home, we flew six days a week through the middle of November. The day after we finished the last airshow, we started the team-building process all over again.

While the differences may seem stark between our operation and yours, the parallels and personalities are an absolute match. Without question, the mission of the Thunderbirds was unique and the expectations for precision were very high. But the makeup of personnel in our hangar was very similar to the composition of your team right now.

Similarities from Team to Team

Any industry in the world includes tens, hundreds, even thousands of organizations that perform the same basic task, build the same kind of equipment, or deliver the same service. Some of those organizations deliver the gold standard and always produce the very highest levels of quality within their industry. Other organizations produce solid, reliable results, and still others struggle to deliver a competent service or reliable product on time.

The difference between high-performing organizations and those that fall short of the gold standard is not just talent but how well leaders develop their team’s draft with the talent they have. Your role in that process is critical, as you will not only plow the path for the people behind you to follow but also set the conditions that will compel them to close the gaps between individuals, elements, and teams—the gaps that slow you down.

Drafting Is All about Closing the Gaps

To harness the effects of drafting and bring trust to bear within your team, you need to focus on closing the gaps. As mentioned, a gap is physical or emotional distance caused by a lack of competence, a lack of confidence, or an unmet social need that degrades performance. Left unaddressed, gaps are momentum killers that will thwart any hope of trust.

gap

Physical or emotional distance caused by a lack of competence, a lack of confidence, or an unmet social need that degrades performance.

The explanation for team members’ gaps varies with both tenure and competence. A new hire will sustain his or her distance until a level of traction—technical competence and social acceptance—makes it safe to close. The reasons for gaps in more seasoned individuals take longer to figure out. Even after their needs are met, the smart ones will take their time closing because, as in our demonstration, distance gives them the reaction time they need to preserve their well-being.

Proximity Narrows Focus

When flying, the closer you get to the lead jet, the greater the demand on your eyes and reflexes to keep you out of harm’s way. The more you close, the quicker you must shift your eyes—your crosscheck—between the leader, the other jets in the formation, and the threats to your well-being, such as the ground. When you are 50 feet back, your crosscheck can be slow and methodical and still allow you to sustain safe separation from the leader throughout some pretty aggressive maneuvering. Close some of that distance, however, and your focus must intensify because the area you can cover in your crosscheck narrows. Close a bit more and you’ll gain some of the aerodynamic benefits from the jet in front of you while preserving just enough reaction time to get out of Dodge if things go south.

crosscheck

Taking stock of your immediate environment by shifting your focus between two or more objects.

You have lived that distance when moving at speed during rush-hour traffic. Your focus on the bumper in front of you gives you little time to check the status and intentions of the cars to your left and right, but, in your mind, your quick reflexes will allow you to react in time to avoid hitting the car in front of you if conditions deteriorate in a hurry.

During one maneuver in our demonstration, the distance between our jets was often less than that from my elbow to the tip of my fingers. If you were driving that close while clipping along at 65 miles per hour, your focus on the car in front of you would take all of your concentration—while you hope that the car you’re trailing holds its speed. Flying that close maximized the effects of our team, but it also reduced reaction times to the point where the pilots on my wing could not save their own lives if I made a catastrophic mistake. Making a living flying that close to a jet moving in all three dimensions—400 feet off the ground at 500 miles per hour—takes much more than faith or concentration; it requires the deepest levels of trust.

Our Thunderbird team spent hundreds of hours together methodically developing every reinforcing input we could collect on one another to close the gaps in our formation. The whole time we were flying over the practice range, a supervisor on the ground was grading our every maneuver. I also knew that there were five other sets of eyes flying alongside me that were watching my every move—watching not just how I executed the maneuvers (my job) but also every other insight they could glean in the air (and on the ground) to see how I added up. They needed to know they could trust me before they closed the gaps to the point where they put themselves at risk on my wing.

The Real Benefits of Closure

The bigger the gaps between you and your followers, the more weight you will carry. Trailers who continually show up late for work, who greet initiatives with antagonism, or who consistently meet deadlines with disappointment can thwart every effort to accelerate your team. Getting those individuals to close the gap of commitment will take that administrative weight off your plate. Draw them further forward into loyalty, and you will have solid performers who serve as advocates that positively shape the attitudes and mind-sets of the team around them. Close the gap of trust, and your empowerment of key players to handle significant efforts will give you more energy and bandwidth to elevate the trajectory of the organization behind you.

How do you close that distance? How do you get your followers to let go of whatever is holding them back? To get them to close those gaps to the point where you realize the surge of drafting, you need to develop a plan to fulfill the needs, the wants, and unfulfilled elements of their working lives. The first step in that plan, the first thing they will look for, is commitment—your commitment to their place on the team.

Drafting’s First Step: Closing the Commitment Gap

The Thunderbirds had 130 team members from 24 different job specialties and career fields throughout the Air Force—and every one of them arrived with his or her own tribal mind-set. We had all been in the Air Force prior to joining the Thunderbirds, but we had never been required to work together in a single hangar. Getting people who identified themselves as fighter pilots, engine mechanics, videographers, public affairs professionals, and the like to shed their stove-piped mind-sets and meld together as a team required a concerted effort. The first step in that process was building commitment, and we did that through our onboarding program.

The impressions that new hires take from the first days and weeks on your team are lasting and will affect their commitment to you and your draft throughout their tenure with the team. The single biggest factor in their long-term commitment is how much their new team values them—how much time and effort you are willing to invest to get them settled in, socially integrated, and technically qualified.

In some ways the more experience a team member has, the more challenging the first steps to commitment might be. Not everyone will fight new goals or course corrections, but even your hardest-working folks crave stability, and getting your people to commit to a different path can be challenging. Even military leaders holding the kind of authority their subordinates have sworn to follow face the same challenges you do in compelling their people to align on a new direction.

People will not always move based on logical reasoning, like the promise of more responsibility or a bigger compensation package, but they will always close on emotions. Your challenge lies in figuring out which emotions to tap to get your followers’ commitment, as well as on your making first contact with the elements and obstacles that slow them down. My efforts to engage every aspect of that challenge began the first week of an individual’s onboarding.

Being genuinely curious about the people behind you and showing interest in their challenges, goals, and dreams will get them to close on the emotion of hope—the hope that you will do something for them in the future. Follow through with one or two of the things you learn along the way, and you can get them to close into the lane of loyalty.

Drafting’s Second Step: Closing the Loyalty Gap

Loyalty is cohesion within a relationship—the kind that can be built only on the foundation of commitment. Once your trailers know that you are committed to their well-being, they will open up and, with a little encouragement, shed their outward personas—their overt positions—and tell you about their real motivations and genuine passions.

loyalty

Cohesion within a relationship—the kind that can be built only on the foundation of commitment. It is fostered by a leader’s willingness to go the distance to support his or her team without the expectation that they will respond in kind.

Most people have several foundational elements or pillars within their lives that drive their actions. At times the important pillars are obvious; at other times they are well masked. With just a little forethought, you can find a trove of information that will help you motivate your people more than any other tangible benefit you can offer. Remember, however, that the performance—and loyalty—of others is often tied to growth in areas that are not directly related to work.

The opportunity to give individuals a leg up or to bolster another central element or pillar in their lives can be a very powerful motivator. Discovering those passions and then helping individuals further them can help bring more of their potential to bear for and within the team. Once you know their passions, you will know how to reach into their chests and begin pulling them forward on their wants and needs. Do that and you’ll instill a sense of your confidence in them and bring on a feeling of unity you’ll both revel in. Only you, the leader, can initiate this action—and you do not want to miss it.

Building respect Moving with the talents, and on the judgment of the people who work for you, is the first step toward empowering them to handle some of your responsibility. In the quest for opportunities to increase the exposure of the Thunderbirds to the public, our team came up with several novel ideas. While public affairs would be the central hub of our efforts, we wanted to get the entire team involved. One of the best ideas actually came from a member of our maintenance team.

Each jet had two cameras that captured spectacular cockpit footage throughout our demonstration. The cameras were there for safety, but if we could figure out a way to share that live footage on the Internet and with local television and airshow audiences, there was potential to increase the number of folks who saw any and every one of our demonstrations.

With a few guiding thoughts and no budget for the project, I asked our maintenance officer to flesh out the idea. Within a few weeks, his team had designed a system around the components of obsolete data-link equipment designed for another aircraft. Giving him my backing to move on a solution his team had dreamt up was an unmistakable sign of my confidence in him.

Once you show your key players that they have your confidence, they will shift their focus from the performance of their roles to how you execute yours. They will watch for your willingness and ability to move others on the goals you claim to hold dear. Like every other aspect of their development, your team’s respect for you needs to be consciously developed. Inspire and reinforce that respect, and you will chamber the kind of loyalty that will last well beyond their time on the team—the kind that will pull them right up to the line of trust.

Drafting at Full Throttle: Breaking the Trust Barrier

Every year our training season culminated at the end of February. In the weeks leading up to our graduation from training, we were flying an entire 36-maneuver demonstration package 500 feet above the ground with all six jets. That altitude, coupled with the training spreads (gaps) between jets, gave every pilot enough reaction time and space to recover from an errant maneuver—but we were about to move beyond that threshold.

The conscious decision to fly even tighter formations at lower minimum altitudes—the ones we’d be flying during airshows—relied on every bit of faith and confidence we had built in one another; we knew the risks went way up from here. Closing the gaps to airshow spreads and lowering our target minimum altitude to 400 feet meant the pad was gone. If I made a catastrophic mistake in the lead aircraft, the peripherals would not allow the wingmen to recognize pending ground impact in time for them to save their own lives. Closing the final gaps and dropping down to airshow altitude required the highest levels of trust.

Trust was a big deal on the Thunderbirds. Since the team’s inception in 1953, 19 men have died flying the demonstration; our lives really did depend on the other team members. Trust may just as well have been written on the inside of our visors—as we looked for it everywhere, constantly taking in every insight, every nuance, that would reinstill our belief in one another.

During our seemingly endless hours over the practice range and through the execution of thousands of maneuvers, we were slowly writing new code on one another—programming code about the people around us that we would use as the basis of trust. Every time I executed my role correctly, or fessed up after I didn’t, I was shaping their insights into my character—consciously pulling them toward trust. Although we made those assessments in the air, the same thing was true for the team members on the ground.

Building trust If it isn’t already clear, your actions as a leader initiate the process of drafting, and the effort required (and the scrutiny you’ll receive) is significant—but the benefits and pride that emerge when you pull your team in tight are extraordinary. This is when your people are close enough to take the weight from your wings and when the efficiencies of drafting are highest. When key members of your team are empowered, you give them your authority to take big efforts off your desk, freeing you up to plan and then elevate the trajectory of the entire team. You will move faster and accomplish more together than you ever could have done on your own.

Developing the kind of trust that leads to a Thunderbird-level of closure can be very powerful. Feeling those jets tuck in to position was as much emotional as it was physical. There is nothing more powerful or electrifying, nothing that will accelerate your team faster or make them want to stay with you longer, than building an effective draft. The secrets, techniques, and lessons that will help you lead your team to that kind of closure are detailed in the chapters that follow. Read on.