Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Entrepreneurs in Every Generation

How Successful Family Businesses Develop Their Next Leaders

Allan Cohen (Author) | Pramodita Sharma (Author)

Publication date: 06/06/2016

Families are complicated; family businesses even more so. Like other companies, family-run enterprises must develop leadership and entrepreneurial skills. But they must also manage family dynamics that rarely mirror the best practices in the latest Harvard Business Review.

Allan Cohen and Pramodita Sharma, scholars with deep professional and personal roots in family businesses, show how enterprising families can transmit the hunger for excellence across generations. Using examples of firms that flourished and those that failed, they describe the practices that characterize entrepreneurial individuals, families, and organizations and offer pragmatic advice that can be tailored to your unique situation.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Families are complicated; family businesses even more so. Like other companies, family-run enterprises must develop leadership and entrepreneurial skills. But they must also manage family dynamics that rarely mirror the best practices in the latest Harvard Business Review.

Allan Cohen and Pramodita Sharma, scholars with deep professional and personal roots in family businesses, show how enterprising families can transmit the hunger for excellence across generations. Using examples of firms that flourished and those that failed, they describe the practices that characterize entrepreneurial individuals, families, and organizations and offer pragmatic advice that can be tailored to your unique situation.

—William S. Fisher, Board Member, Gap Inc.

“Allan Cohen and Dita Sharma have written a highly insightful, clear, and pragmatic argument that innovation in family companies is essential for multigenerational success. This will help families understand how to innovate in every generation and how to develop leaders who can bring about needed change in the family business.”

—John Davis, Chair, Families in Business Program, Harvard Business School, and Chairman, Cambridge Advisors to Family Enterprise

“The entrepreneurial spirit in my family and our business has been one of the most important factors in our continued success through six generations. Finally, a book that not only acknowledges the importance of entrepreneurship to the long-term success of family businesses but also provides a practical guide to families who want to keep that entrepreneurial spark alive from generation to generation. This book is a joy to read and will transform the way you think about families in business.”

—Sylvia Shepard, former Chair and Founder, Smith Family Council, Menasha Corporation, fifth generation

“This is the clearest and most comprehensive list I have ever come across of all the key practices necessary to ensure the development of the entrepreneurial spirit in every generation. This ‘Magna Carta' of transgenerational entrepreneurship should be made compulsory reading for all members of family businesses.”

—Cyril Camus, fifth-generation owner and CEO, House of CAMUS Cognac

“I am so excited to see that finally a book has been written on entrepreneurship through generations. Entrepreneurship is generally abundant in the founder, and somehow the desire to do something different starts to fade away with the next generations. In my family I encourage and support entrepreneurship for the next generation.”

—Surya Jhunjhnuwala, founder and Managing Director, Naumi Hotels, Singapore

“Cohen and Sharma adopt a distinctive structure that advances the discussion of entrepreneurial issues in families and includes chapters that describe what to do and how to go about doing it. The text is inspired by research evidence and introduces key concepts that are illuminated by some recognizable family business cases drawn from many countries. The research does not clutter the presentation but rather highlights the intellectual origins of the ideas described.”

—Ken Moores, former President, Bond University, and Consultant and Executive Chairman, Moores Family Enterprise, Australia

“Entrepreneurs in Every Generation is an inspiring read. Not only do the authors beautifully tie in the important role entrepreneurship plays in the sustainability of family enterprises, but they also provide real case studies and tools for change. A must-read for business owners and their families.”

—Ramia M. El Agamy, Editor-in-Chief, Tharawat magazine, Dubai and Switzerland

“This new book by two well-respected academics in the family business field integrates insights from psychology, strategy, and change management with cases studies from family companies around the world. An interesting and readable book that is especially useful for next generation family business members.”

—Judy Green, PhD, President, Family Firm Institute

“Cohen and Sharma shed light on the key points needed to ignite the entrepreneurial spark within generations. They bundle this up in a beautiful and interactive way. A great read!”

—Willy Lin, Managing Director, Milo's Knitwear and Milo's Manufacturing, Hong Kong, second generation

1. Secrets of Successful Entrepreneurial Leaders

2. Developing Entrepreneurial Leadership Skills

3. Secrets of Successful Enterprising Families

4. Developing Enterprising Families

5. Secrets of Entrepreneurial Organizations

6. Developing Entrepreneurial Organizations

7. Action Planning—a Question of Balance and Timing

Chapter 1

SECRETS OF SUCCESSFUL ENTREPRENEURIAL LEADERS

Long-term business survival depends on effective entrepreneurial leadership—not only from the founders, but equally importantly, from each subsequent generation that runs the enterprise. In this, the first of our “what it is and why it is important” chapters, we describe the essential characteristics of successful entrepreneurial leaders and the unique challenges and opportunities in building these attributes in family firms. Clarity on these points will help us to discuss in chapter 2 how next-generation members can take initiatives to grow their entrepreneurial leadership skills and how other members of their family can support such endeavors to nurture and grow entrepreneurs in every generation.

An Entrepreneurial Leader

At the core of entrepreneurial leadership is the constant willingness to seek unfilled needs and at least to consider whether it’s possible to provide a usable solution. Identifying critical elements of such leaders is harder than it sounds. It is a lot like playing golf; from a distance it looks easy, but a new player’s progress is thwarted by many hazards, only a few of which are actually visible. Just as golf is not a modified version of baseball, cricket, or soccer but a unique sport in itself, entrepreneurial leaders are also not simply entrepreneurs or leaders but a unique combination of both.

Such leaders can be introverted or extroverted, dominating or encouraging, determined or flexible. In fact some may not even be easily recognized as formal leaders even though they are highly influential. William McKnight is such an example.1 Although his is not a household name, he is credited with laying the basic management principles for 3M. Founded in 1902 as a mining company, 3M had a rocky launch and became financially stable only in 1916. McKnight joined the company in 1907 as the assistant bookkeeper, over time rose to becoming its president, and retired in 1966 as its chairman. In 1948 he developed the following principles that helped propel this company into one of the most innovative companies in the world.

As our business grows, it becomes increasingly necessary to delegate responsibility and to encourage men and women to exercise their initiative. This requires considerable tolerance. Those men and women, to whom we delegate authority and responsibility, if they are good people, are going to want to do their jobs in their own way.

Mistakes will be made. But if a person is essentially right, the mistakes he or she makes are not as serious in the long run as the mistakes management will make if it undertakes to tell those in authority exactly how they must do their jobs.

Management that is destructively critical when mistakes are made kills initiative. And it’s essential that we have many people with initiative if we are to continue to grow.2

Notice the essential role of delegation, initiative, and mistakes in building an enterprise that is entrepreneurial at all levels over time. Nevertheless, media and historical accounts tend to depict entrepreneurs as confident solo swashbucklers who almost mystically came up with a brilliant insight, knew exactly how to proceed, and quickly developed a successful enterprise. In generational family firms, the failures, trials, and tribulations of the founding or earlier generations often acquire a heroic coating as the stories get transmitted over time. The path to success is seldom straight, with many experiments, failures, explorations, and small discoveries before success.3 Usually success is achieved by incredible persistence, yet some very persistent entrepreneurs have doggedly marched over cliffs into the sea, ignoring the signals that they should have changed course.

Entrepreneurial leaders know that the success rate of new ventures is disappointingly low.4 Yet research is unequivocal: first-generation family firms enjoy better financial performance than nonfamily firms, but from the second generation onwards the results are mixed.5 That is, some do better while others flounder. Researchers continue to investigate why some family firms flourish over generations while others fold after the founders’ tenure. Meanwhile, enterprising families that do well past the founding generation rely on building entrepreneurial and leadership skills of every generation.6

The path to success is seldom straight, with many experiments, failures, explorations, and small discoveries before success.

The good news is that entrepreneurial leadership skills can be developed with mindfulness and practice. Envisioning something new and delivering value—the crux of entrepreneurship—must be seamlessly integrated with inspiring others to suspend self-interest and reach high performance to make the leaders’ vision a reality. Neither is sufficient without the other. An entrepreneurial leader needs to be equally comfortable leading and being led, staying on and changing course. Prudence lies in knowing when (and how) to lead and when (and how) to follow, when to start something new (and what this new thing should be) and when to stay on course. Often choices have to be made between two rights—such as achieving balance between the interests and dreams of the incumbent generation and those of the next generation, exploiting all possibilities of current markets while exploring future opportunities, fully engaging the most competent next-generation family and nonfamily members. Time and timing matter! Ambidexterity7—which literally means using both hands with equal ease—is the name of the game.

Not only must individuals at the helm of family enterprises simultaneously deploy entrepreneurial and leadership skills, but it is equally important that they prepare their organization8 and family to be fertile grounds that encourage the development of these skills in the next generation. While we leave the discussion of family and organizational factors that enable such skill development to later chapters, let’s turn our attention to what it takes to be an entrepreneurial leader.

Ambidexterity

Leadership effectiveness is about innovation and constant adaptation, but this is only part of the story. By definition, entrepreneurial leaders are innovative, finding new ways to fulfill unmet needs. This requires them to be flexible and intuitive. They must look closely at situations to decide whether a feasible solution exists or not. Although a combination of close observation of people and some analysis can make plain an unmet need, it often requires an intuitive leap to see the value-creating opportunity that is within the capacity of the entrepreneur and his or her resources. For family firms already in existence, exploration for new opportunities and exploitation of existing markets and products must be juggled simultaneously, requiring leaders to make judgment calls on how much time and resources to invest in each.9 A flexible, intuitive approach must be complemented by equally strong disciplined analysis and precision. In generational family firms, the leaders must not only be clear about their own vision for the family enterprise but must also have the courage to acknowledge that the next generation’s vision may not be fully synchronized with theirs. It is a delicate art to decide how far to pursue one’s own vision and when to “let go” so as to make room for the next generation’s vision to “take over.” Wisdom lies in being sufficiently disciplined to achieve the precise combination of commitment and detachment that good judgment demands.10

An entrepreneurial leader needs to be equally comfortable leading and being led, staying on and changing course.

To better understand the ambidexterity of entrepreneurial leaders, let’s look at two founders who grew their respective enterprises to global leadership positions before passing them to the next generation of family leaders. Both are remarkable in their own ways, influencing not just their industries but the lives of thousands of employees and customers. Notice their ambidexterity in switching between entrepreneurship and leadership and the ways their leadership styles may have changed as their enterprises grew from new ventures to global brands.

At age seventeen Fred Deluca launched what we now know as Subway Restaurants when his father’s friend and a nuclear physicist—Dr. Peter (Pete) Buck—encouraged him to open a submarine sandwich store and lent him a thousand dollars to do so. Fred’s motivation was to earn some money for medical school. In addition to Pete, Fred’s parents, sister, and wife were all critical to the launch of this new venture in 1965 and its subsequent growth. Fred died shortly after celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of his company in 2015. By this milestone anniversary, he had led this family enterprise to become the largest submarine sandwich chain in the world with over 37,000 stores in over 100 countries. His sister Suzanne Greco, who has been involved in different roles with the company since its inception, is now the president and CEO of this family business.

While Subway’s growth has been remarkable, it has not always been a smooth ride. Although apparently from the beginning Fred had the idea of offering healthier, less fattening food than existing fast-food chains and big dreams for expansion, the first two shops were not profitable. They were not in good locations, which were necessary for the success of sandwich shops. They required name changes, and the growth of the chain was much slower than the self-imposed goal of opening thirty-two stores in the first ten years. But Fred’s dogged persistence and his partner’s trust in him continued. Only when Subway finally moved to a franchise model did the company begin to expand more rapidly, achieving and often exceeding its goals.

Despite major law suits from franchisees, over the years Fred remained sufficiently hands-on to be sure that the company stayed in touch with the needs and interests of customers and that the shops maintained high quality, sanitary conditions, and excellent service.11 With continuous incremental innovation, such as the addition of avocados on sandwiches, the introduction of Flatizza (a flat bread sandwich), and vegetarian Subway stores in India, this family enterprise has endured over time. An ambidextrous entrepreneurial leader, Fred could alternate between the dream and hands-on execution as needed.

Entrepreneurial leadership is not only the forte of founders in food services industry like DeLuca but also evident in other contexts. Like Subway, Lamborghini is today a world-famous brand. Might it surprise you to learn that it was only early in the 1960s that Ferruccio Lamborghini designed and manufactured his first car? While passionate about engines, he originally focused on repairing cars and motorcycles during World War II and then on designing powerful tractors to support the needs of local farmers in his native Emilia Romagna region. Only when Enzo Ferrari rebuffed him for proposing improvements to the Ferrari car did Lamborghini resolve to design and manufacture his own car. It took him nine months to design an elegant and powerful vehicle that was brought to market within two years. With a staunch belief in technical excellence and quality, Ferruccio led his enterprise through high and low times until he was in his seventies. Then one day, he is known to have unceremoniously handed over the keys and operations to his son Tonino, making himself available once a year for business-related discussions.

At the time of this unpretentious changing of the guard at Lamborghini, Tonino was a university student in his early twenties. Deeply familiar with the business because he had played in the premises as a child and worked there every opportunity he got, Tonino wanted to prove himself as an entrepreneurial leader who could build on his family’s legacy. When the family sold its car brand to the Audi Volkswagen group, he embarked into luxury watches. In an interview with Tharawat12 he recalls that his father was not too keen on the idea of starting a fashion and luxury business. But, being a fair man with an acute sense of balancing between the needs and desires of the current and future generations, he said:

You know, I always did what I wanted to do, so why shouldn’t you get your chance?

(Tharawat, June 21, 2015)

However, the senior Lamborghini emphatically reminded his son that the family name stood for technical know-how and mechanical excellence. Today, the third generation of the Lamborghini family is determined to continue to innovate and regenerate so they can keep ahead of the curve and contribute to their family enterprise.

Founders Fred DeLuca and Ferruccio Lamborghini were both able to evolve their entrepreneurial leadership styles as their companies grew. For the endurance and longevity of organizations under their charge, they knew to simultaneously focus on exploiting current markets while exploring new directions,13 so as to build on the past while staying focused on the future. Without this combination, enterprises stagnate, flounder, fail to adapt to changing conditions, or slowly deteriorate beyond the tenure of such an individual. Only time will let us know if Fred DeLuca’s Subway will fare well past his time at its helm after his recent death and if each subsequent generation of the Lamborghini family will continue to build on their founders’ legacy.

The ambidextrous mind-set has been variedly referred to as “the genius of the ‘And’” in Built to Last by Collins and Porras and “the opposable mind” by Roger Martin. Based on their decades of experience with multigenerational families around the world, Amy Schuman, Stacy Stutz, and John Ward look at Family Business as Paradox.14 They conclude that the most enterprising families not only learn to manage such contradictions but find ways to turn them into secrets of success. For example, based on his forty-three years of experience leading the Murugappa Group of India, patriarch M. V. Subhiah notes that not only must they maintain a style befitting the size of their operations, but they must simultaneously preserve the moderation and humility that are core values for their family. While such integrative thinking is said to be at the core of great companies and visionary leaders, it is surely not easy to implement. Consider the comments of Rupert Murdoch, a second-generation member of a media family from Australia. A controversial yet highly successful entrepreneurial leader, he grew his father’s news business into a global media conglomerate valued over $80 billion today. In an interview with Fortune he noted:

Print is going through a tough time. You’ve got to keep improving and competing in a new world, as well as keeping your old world going. … I hope we are not wasting money, but we’re spending it.

(Fortune, April 28, 2014)

Next-generation leaders like Rupert Murdoch, Suzanne Greco, and Tonino Lamborghini, who follow successful founders, face the dilemma of balancing tradition and innovation, creativity and operational excellence. It turns out that most people are (at best) naturally good at only one or the other. Some individuals, like Fred DeLuca, can learn to personally be good at both creating and building, while others have to recognize that when the opposite of their strength is called for, they have to find others—family members or outsiders—to complement them. In family enterprises that grow and sustain over generations, we can identify ambidexterity as five diametrically opposed core skills:

• Awareness of self and surroundings

• Building a dream and a team

• Influencing and directing

• Beginnings and endings

• Learning and unlearning

Let’s look more closely at each of these core capacities.

Awareness of self and surroundings. Why do we first turn to self-awareness? People don’t always think of this skill in relation to effective leaders. Yet there are at least three reasons to identify this capability when considering entrepreneurial leadership over generations. First, starting a new venture almost inevitably requires extraordinary time commitment and emotional investment from whoever initiates it. Even more energy and commitment are required when building something new and worthwhile within or related to an existing business, as the organizational culture and routines have already been established. Enterprising families understand that leaders from the next generation must operate in this context. When the activity demands total preoccupation, it is almost impossible to sustain it if it does not engage the personality, values, and passion—the core—of the leader. If individuals are forced into situations that do not tap what they care most about, they may find it hard to put in the necessary thought and effort or feel a vague malaise that they can’t quite identify. But when there is alignment, it is possible to soar. Entrepreneurial leaders, therefore, have to be enough in touch with their inner being to choose to pursue only those opportunities that will completely capture them. This sense occasionally may be blindingly obvious, but more often it comes from diversity of experiences that lets someone identify what feels natural and effortless, a calling that fully engages an individual—that perfect “hand in glove” fit!

Second, the family history and legacy often weigh heavily on the psychology of the next generation of family members. For example, when he remembered the moment his father handed him the keys to the business, second-generation family member Tonino Lamborghini confessed to Tharawat: “Of course, I was scared. Here I was, still at university, and my father just hands me his life’s work.”15 This feeling of responsibility and stewardship continues over generations, for the third-generation member of the Lamborghini family Ferruccio (named after the founder) remarked: “Yes, of course there is the need to live up to the expectations of this brand and this myth.” Enterprising families know that if family members of the next generation start their career against such backdrop, they will need extra courage and opportunities to understand their true capabilities and interests. Casual interest in trying something out because there might be economic possibility often is not enough to overcome the aura of the family traditions. Genuine alignment with what really matters to next-generation leaders is the powerful energy source that can fuel these entrepreneurs when the going gets tough, which is inevitable when undertaking new initiatives.

Enterprising families and the individuals therein realize the critical importance of helping all family members to discover their true interests and talents. For example, Carole Hübscher, chair of Caran d’Ache’s board of directors, whom you may recall from the last chapter, notes that “unless you are passionate, and you’re really willing to join the family business, there is no point in forcing anyone to do so.”16 Research shows that four different reasons motivate next-generation members to pursue a career in their family firms. These are desire, obligation, greed, and need. While each decision combines these factors in different proportions, those propelled mostly by desire or obligation turn out to be much better leaders and performers, reporting higher levels of job satisfaction than those motivated by greed or need. Unfortunately, those who join their family businesses because of need (because they lack confidence in their ability to be productively employed in other spheres) are the weakest leaders of all.17 In short, unless a person’s heart is in it, it just won’t work in the long term.

Entrepreneurial leaders, therefore, have to be enough in touch with their inner being to choose to pursue only those opportunities that will completely capture them.

Third, successful leaders must know themselves in order to be able to engage needed others. It is impossible to do anything impactful alone, so leaders must be able to inspire, align, direct, motivate, and influence diverse and talented people. In order to do this effectively, it is critical for an individual to know his or her core strengths, limitations, interests, and even biases, as each succeeding generation must operate in an increasingly diverse work place. Think, for example, of what happens to a leader who at some stage of life has been deceived by trusting a friend too much. Seared into the leader’s psyche is a deep distrust of people who appear to be friendly. While this suspicion can be helpful in sorting charlatans from others, it can also cause the leader to be so suspicious that good people are driven away or kept so at arm’s length that they cannot give their best.

Most of us are susceptible to “The Danger of a Single Story,” as eloquently described by notable Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. She recalls18 how characters in the stories she wrote as a child growing up in Nigeria mimicked those from the British and American books she read. Her characters were always white, had blue eyes, played in the snow, ate apples, drank ginger ale, and talked a lot about the weather, saying how lovely it was that the sun had come out. None of these made much sense in her Nigerian context, for she and most around her were black with brown eyes, ate mangoes, had never experienced snow, and had no reason to talk about weather, given that it varied little year round. Each generation has its own set of experiences, but the power of the stories about past experiences often have a deep impression on the next-generation members.

In a family business this might show up as an unwillingness to ever trust a nonfamily member or perhaps an unwillingness to trust any inlaw who wants to be part of the family business. Conversely, another leader might have had bad experiences working for an autocratic boss and would come away from that experience determined to never give strong directions to anyone, assuming that everyone prefers the kind of autonomy that she or he longed for. Such a leader might write off as too dependent those subordinates who ask perfectly reasonable questions about direction or best methods, thus denying them a chance to learn and grow. Leading without self-awareness can thus get in the way of effectively making needed changes. As the McKinsey Consulting firm concluded from a recent study:

Many people aren’t aware that the choices they make are extensions of the reality that operates in their hearts and minds. Indeed, you can live your whole life without understanding the inner dynamics that drive what you do and say. Yet it’s crucial that those who seek to lead powerfully and effectively look at their internal experiences, precisely because they direct how you take action, whether you know it or not. Taking accountability as a leader today includes understanding your motivations and other inner drives.19

Awareness of self also helps to build awareness of surroundings, both context and people, which in turn aids in selecting and inspiring a talented team. Many entrepreneurial leaders aren’t particularly aware of their unique competencies and judge harshly those who cannot easily do what they do naturally. Have you ever seen a numbers whiz glance over a column of figures and focus in immediately on the one that is incorrect or problematic? Because the person is so good at it, he or she is driven crazy if an otherwise competent subordinate either has no intuitive feel for such issues or takes four times as long to discover them. This situation can be made worse when the leader has deep experience in the industry or business and is perpetually impatient with family members or employees who lack the same base of experience and therefore are not as efficient or proficient. Furthermore, if the passionate, expert, and focused leader has earned self-confidence over the years and responds impatiently to those not as far along as they are or is sharply critical when pointing out what the others do not see, the next generation can end up not seeking or receiving positive feedback. This makes it really hard for either generation to gain confidence and trust in the abilities of the other. The negative spiral continues, distancing the juniors from the family and firm.

Genuine alignment with what really matters to next-generation leaders is the powerful energy source that can fuel these entrepreneurs when the going gets tough.

Enterprising families that successfully prepare entrepreneurs in every generation realize the advantages of next-generation engagement and work hard at it. For example, Sylvia Shepard, a fifth-generation owner of Menasha Corporation and the chair of the Smith Family Council, notes:

Family business can have significant advantage over nonfamily business if they use their next generation as a barometer of change, and as a window into a new reality that the previous generation might not fully understand. If the family has done its job of preparing children for ownership and leadership, this next generation will act as the innovation engine for the company. They will provide the spark that enables the family firm to grow and prosper amid changing market realities. The family just needs to listen and be poised to respond to its young people.20

Creating organizations where the leader, and everyone else, wakes up every morning excited and loving what they do is at the heart of what enterprising families aim for so that all family members experience a positive environment to identify a project or a venture to devote their energies toward. Such excitement is built into the core of such families regardless of whether they are start-ups or generational enterprises as indicated by these two examples. In 2011, sisters Zania and Rania Kana’an launched a website, Ananasa.com, to sell worldwide the unique products of the artists and craftspeople of the Middle East. When the company was in its infancy, both sisters worked in corporate jobs but were not satisfied, for they were not learning and could not realize their aspirations. They simply decided that they wanted to wake up every morning excited and loving what they did, thus they launched their own company.21 Similarly, Charles S. Luck IV, the third-generation leader of the Luck Companies—one of the largest producers of crushed stone, sand, and gravel in the United States—wants “everyone to have a job at the company that exceeds their wildest dreams.”22

When working in family firms, the family members of the next generation are under constant scrutiny not only from the senior generation but also nonfamily employees, customers, suppliers, bankers, and other key stakeholders. Going the extra mile while being in the public eye necessitates natural effort that comes only with strong awareness of self and others.

Building a dream and a team. At the core of entrepreneurial leadership is the ambidextrous capacity to envision a desirable future and paint a vivid picture of it that can inspire and excite others to build a team to help shape and then make the change. The imagined future can involve a new product, service, market, or process that is meaningful and valuable to at least some other people. Effective leaders can not only conceptualize and talk a good game but also have a knack to figure out how to actually bring the dream to fruition. Not only must they have a heightened sense of the steps necessary to make something real, they should also have a clear understanding of the required resources—those available and others where there are gaps. Finally, they must have the finesse to get past the obstacles: human, organizational, resource, legal, and others. The mere dreamers get written off as impractical big talkers, and those who only keep their noses to the grindstone without knowing why it is worth bothering and what they can create get written off as unimaginative plodders. While the dreamers see only the green blur of a forest without noticing the trees or leaves or rocks within, the doers without vision see only particular trees or leaves and not the pattern or potential of the whole.

Where does this dual capacity to both conceptualize and deliver come from? At times, it is a by-product of intimate familiarity with how people live or work, their problems and struggles, regardless of whether they themselves recognize it as a problem. For example, many are familiar with the grand vision of Steven Jobs at Apple, leading with a concept of aesthetically beautiful products that combine hardware and software that provide new access to music or the idea of mobile phones that do many functions not formerly expected in phones. An inspiring example from the other side of the globe is the story of Doctor Govindappa Venkataswamy, founder of the eye clinic Aravind, which performs cataract surgery at no charge (patients pay what they like, up to market rate); the clinic has performed over 200,000 surgeries, saving thousands from eventual blindness. By 2010 the expanded Aravind system was seeing more than 2.5 million patients and performing more than 300,000 surgeries a year.23 He was driven by a spiritual need to cure blindness and serve the poor, and his belief was so intense that over 20 family members, trained at the best Western medical schools, joined the company to do surgery at extremely low wages. But Aravind uses the most modern business practices to drive down costs, speed up all aspects of the surgeries, and raise quality, all of which make the model more viable. Higher throughput, for example, reduces the cost per operation, which allows profit even at low revenue rates and attracts more patients, even those who can go anywhere for their eye care. The combination of the dream and extraordinary team execution are amazing.

It is impossible to do anything impactful alone, so leaders must be able to inspire, align, direct, motivate, and influence diverse and talented people.

Another kind of inspirational story involves co-founders L. S. “Sam” Shoen and his wife, Anna Mary Carty Shoen, who in 1945, with barely $5,000 in hand, set out to create U-Haul when the concept of renting a trailer from one city and returning it in another was unheard of.24 The couple tried to move their own possessions from Los Angeles to Portland, Oregon, after Sam returned from the US Navy, but they could not find anyone who rented one-way trailers, thus spotting a market need and starting a new industry. According to their website, today “the annual mileage of North American U-Haul trucks, trailers and tow dollies would travel around the Earth 177 times per day, every day of the year.” What a dream and remarkable growth in about seventy years! The Shoen family has had its share of trials and tribulations on the family dimension as Anna Mary died early after having six children, and Sam Shoen went through multiple marriages, having thirteen children who did not always get along. Today, two of Anna Mary’s sons, Mark and Joe Shoen, are at the helm of this family enterprise.

The vision does not necessarily have to come from only one of the founders but can also be triggered by leaders of enterprising families from later generations, like that of Andrew Beale, managing director of Beales Hotel in Hatfield, England. This eighth-generation leader was the driving force behind the transformation of a lodge into the four-star Beales Hotel, catering to families desiring to gather together.25

Creating organizations where the leader, and everyone else, wakes up every morning excited and loving what they do, is at the heart of what enterprising families aim for.

Family business can be a source of long-term dreams pursued over generations but also a series of filters that prevent the vision from taking root or keeping it totally out of reach. Let’s talk about the generational pursuit of dreams first. Describing “shared dreams” of a family as the beacon that provides direction to the family enterprise over generations, a renowned family business educator, writer and advisor Ivan Lansberg notes:

The Shared Dream is a collective vision of the future that inspires family members to engage in the hard work of planning and to do whatever is necessary to maintain their collaboration and achieve their goals. It shapes the choices made at every point in the succession journey, from the company’s strategic plan, to the selection of future leaders, to the type of the leadership structure it will adopt in the next generation.26

Enterprising families are often anchored by a shared dream of excellence in something—highest quality products, lowest prices, fastest delivery, or other areas. Efforts are made to imbue and modify the specifics of this broad anchoring dream so it becomes aligned with the core strengths and interests of each generation of leaders. For example, Gerry Ettinger founded Ettinger in 1934 to create luxury goods that would be known for quality and innovation not only in the United Kingdom but also in other European countries. When his oldest son Robert Ettinger came to the helm of the company, the shared family dream continued and expanded to markets beyond Europe. When Ettinger expanded into the Japanese market, some orders were rejected for not meeting customers’ quality standards. As the company prided itself on quality products, Robert personally went to Japan to see what was wrong. He realized that each piece was inspected to ensure an identical number of stitches per inch. If they failed this demanding test, the pieces did not pass the inspection. Changes were made to the production process to meet these exacting standards. He says, “We know that when our Japanese clients approve, the rest of the world will be delighted.”27

While in the Ettinger case, the family history worked to reinforce commitment toward the shared dream, in other instances the past can serve as a giant impediment. Families can become averse to risk in their desire not to jeopardize the family wealth, may avoid going into new directions even when the old industries are no longer vibrant, or choose not to trust nonfamily members in positions of responsibility even when no competent family is available to fill a role. A very strong founder can be so dominant that younger family members do not dare to think about doing anything different for fear that they will not be given the chance to try, or even worse, be ridiculed for suggesting something that is different. The self-fulfilling prophecy of individual talent is confirmed by research in settings varying from elementary schools in San Francisco to trainees in the Israel Defense Forces, to employees in banking, retail sales, or manufacturing.28 When a randomly selected set of students, trainees, or employees are labeled with positive descriptors such as “late bloomers” or “gifted” that indicate their superior abilities or talents, the behavior of these individuals and their superiors is unintentionally modified. The senior starts to pay more attention to the junior, raising expectations by showering praise and encouragement. The junior responds by taking more initiative and working harder, leading to superior performance that further reinforces the positive loop.

Going the extra mile while being in the public eye necessitates natural effort that comes only with strong awareness of self and others.

The reverse effect is equally strong. For example, for many years women and minorities in organizations appeared to have low aspirations. This attitude was reasonable if people lived in an era when they were highly unlikely to be given responsibility or advancement no matter how talented they were. But their aspirations rose dramatically when some chance or circumstance gave (or thrust upon them) more responsibility.29 Sadly, powerful incumbent leaders often perceive this kind of reaction to low opportunity by juniors as evidence that no one in the family is ready to take over, which perpetuates their discouraging behavior. Such attitudes might well be a result of some particular family or family business event where things went wrong, with extreme caution overlearned as a result. Of course at times such caution can serve as the brakes that help preserve a family company through tough economic crises. But enterprising families make mindful efforts to trigger the imagination and aspirations of each generation.

But even vivid dreams require others to make them real. A central yet sometimes overlooked skill is the art of deciding who else is needed, recruiting them by helping them connect to the dream, then working with them to at least launch the first phase of implementing the dream. It is no small feat to find a way to talk so vividly and compellingly about something new that others who are needed for their knowledge, talent, resources and connections—family members or not—want to join. But someone without the capacity to attract and work with people who have complementary skills will find it hard to build an organization.

Sometimes the only other key player is a spouse or sibling, sometimes a son or daughter or parent, and at other times a close friend or friends; related or not, the key players must have sufficient trust to move forward. Family members can have an advantage because of their shared experience and trust when it exists. For example, beyond their academic training and work experience, part of what has allowed the Kana’an sisters to successfully build not only their first venture Ananasa.com, but also their second one, ChariCycles.com,30 is the trust between them. As Rania explains:

“Zaina brings a lot to the creative side. She has that Salvador Dali type imagination and implements it in the business. This is great because she is mainly in charge of marketing.” Zaina in turn … muses, “I can’t visualize not having Rania in my team; to me she symbolizes total honesty. Because we are sisters we can be totally honest with each other and there is much less miscommunication.” Both … agree that it is mainly the high degree of respect that they have for each which makes the collaboration successful; that and … aware[ness] of each other’s skills and shortcomings … Rania … explains that the advantage of their collaboration stems chiefly from their differences and from how their characters complement each other … “The good thing about our relationship is that we forgive each other really quickly. We have our conflicts out when they happen and then know to let them go quickly. I think this is something I would recommend for anyone working with family members.”31

In other instances, accomplishing dreams requires building a team of talented outsiders. Working in a team and working through others are quite different skills. To be effective team members and leaders requires an individual to be adept at influencing as well as directing and knowing the time and place for each. We turn to this ambidexterity next.

Influencing and directing. Incumbent leaders have considerable power to invent and assign roles, determine and administer pay, reward the desired or punish the undesired behavior, and promote or terminate employees. With authority, however, comes responsibility. These leaders must also make difficult decisions and forge ahead under great uncertainty, knowing well the painful consequences if they miscalculate. These leaders control the budget and strategic direction of the company, often serve as the emotional anchors and crucibles of values that help distinguish right from wrong, and are the central nodes of important social networks. Thus, they have the ability to provide or withhold financial, social, and even emotional support. In families, there is ample research to indicate the root cause of sibling rivalry is the desire for the precious yet limited resource of parental attention.32

Enterprising families understand the difference between directing and influencing. Each has an important role to play in the operations of a business. Directing is geared toward making sure the current projects are completed and products delivered in time to existing customers. Influencing, on the other hand, engages the whole person to give his or her very best effort and take the initiative to ceaselessly fine tune so things are done a bit better every day. Getting such attention from the very core of another individual builds on empathy and a good understanding of the aspirations and dreams of the other. There is a difference between the specifiable part of the job, which is captured in job descriptions, and the unspecified, fuzzier component of the job that is left to discretion. Rarely does excellence and true difference come from handling the specified components exceptionally well. Instead, it is what is left to our discretion that helps build entrepreneurs in every generation.33 Both directing and influencing require finesse in communications. Such articulation requires practice. Perhaps even 10,000 hours of practice is required to build outstanding skills, as Malcolm Gladwell argues in Outliers.

Increasingly leaders need to gain cooperation when giving directions not sanctioned by their formal role, or they will be readily ignored. In any organization, even the powerful top person will have to deal with key outsiders who are not obligated to listen. Examples may include government officials who can create or implement regulations, bankers or other funders, boards of directors, vendors, and certainly customers—all of whom are under no obligation to accommodate the interests and desires of the organization’s leader. In complex organizational settings, with multiple technologies and specialties, various product lines, diverse locations, and so on, leaders increasingly must rely on their ability to influence the people who may work for the same overall company but have differing expertise, objectives, ways they are measured, allegiances, ways of working, or basic views of what behavior will best help the organization.

While the dreamers see only the green blur of a forest without noticing the trees or leaves or rocks within, the doers without vision see only particular trees or leaves and not the pattern or potential of the whole.

The capacity to influence is a central requirement for entrepreneurial leaders to get things done in any organization,34 but it takes an even more profound meaning in family firms. By the time members of the next generation begin their career in family firms, the rules and operational practices are already in place. Family members who may or may not have a significant involvement in the business may feel entitled to voice strong opinions simply by virtue of their hierarchical position in the family structure. And when they do have ownership roles, even without executive responsibilities, their sense of entitlement often becomes even stronger and more legitimate. For example, the Illinois Consolidated Telephone Company was founded as a small-town telephone company in 1924. Richard A. Lumpkin, the fourth generation to lead this family enterprise, faced significantly different dynamics than his father did when he took over as the sole owner of the company. Upon the death of Richard’s father, the stock was passed to fifteen family members who were scattered across the country.

Enterprising families are often anchored by a shared dream of excellence in something.

While Richard was named the trustee of his father’s trusts and had effective control of the company and the board voted him to succeed his father as the CEO, suddenly he found himself in a position of having to convince many more family members before he could take any significant initiatives in the company.35 Given the overlapping roles between business and family, this had to done rather delicately to avoid awkwardness in family gatherings or (worse still) to end up with distressed family members whom he might have to buy out. Thus, as the next-generation leader he had to learn to hold discussions with and often times influence the key stakeholders in powerful positions.

Not only is the number of stakeholders often much larger in family enterprises, the opportunities to build directing and influencing skills can be a major challenge. Too often the leadership roles in both the family and the business are held by the same people or members of the same generation.

The members of the next generation may find themselves in vice president positions rather quickly, often cutting short the necessary learning time of each previous stage of their career ladder. However, they then often spend much longer time in this penultimate position than their counterparts in nonfamily firms.36 This is largely due to the multigenerational stack-up caused when the incumbent generation lives longer and healthier lives and has extended leadership tenures.37 While the incumbent leaders are well positioned to build their directing and influencing skills, how do enterprising families create opportunities for the next generation to hone these skills? In the next chapter, we will discuss some ideas that such families have found helpful.

Beginnings and endings. The popular image of entrepreneurs is that they create something new and are huge risk takers. As we discuss below, both these images have a bit of a counter side to them. While entrepreneurs often do create something new, as Joseph Schumpeter argued, within each creation lies some destruction or the ending of something—be it resources in the form they earlier were, time of the individuals involved, or the market before the new creation. Although Schumpeter focused on the economic structure, the concept applies equally well to new beginnings in family firms, as these new beginnings often come at the cost of some exits that help to free up time and resources to invest in the new.

Taking entrepreneurial action is conditioned as much by attitude towards risk as it is by objective risk. Entrepreneurial leadership is unlikely to occur or to be passed along to younger generations without some kind of belief that preserving the status quo is not necessarily safe and that finding a new and better way to do something is not automatically prohibitively risky. Past decisions, even when successful, are seldom good forever. Successful entrepreneurs, in order not to squander scarce assets, often must be willing to end an activity—a project, a business line, a product, a once promising expansion, a job, a location—no matter how fond of it they are. “That’s my baby” can be a beautiful sign of deep investment and loyalty or a of tragic unwillingness to let go. As Danny Miller’s book The Icarus Paradox notes, the very same things that created success, when taken to excess, can cause decline and failure.

Over generations, some family firms stay in the same industry in which they were founded, while others evolve into different industries, markets, products, or size. Regardless of how much the enterprise changes over its life course, the path of generational family firms is marked by endings or exits to make way for the new as the context and conditions change. Paradoxically, even standing still in the same location and industry requires change. For example, while Bremen Casting, a machine shop started by three foundry men in a garage in 1939 to make castings for furnace grates, has stayed in the same location and business for over seventy-five years, the company looks very different today. Although still based in its original building, the facility has expanded from 5,000 to 130,000 square feet. It has developed from three men working in a garage in the 1930s, to a factory run on manual labor in the 1960s, to an automated foundry that runs 24 hours a day in 2014. James Brown, the fourth-generation president of the company, remarks that although Bremen Castings is in the same business in which it started, “the company itself looks very different. Reinvention of the company has been key to its survival.”38 In this company, each generation reenergized the business. With each evolution, the previous era ended. Thus leaders must have not only the wisdom to make changes and investments but also the ability to handle the closures as well as transitions. Such changes test the mettle of two generations, requiring the baton to be passed not only in terms of leadership change but also what each leader brings to the company. Practice is needed for both—to start something new and to end the ways of the past.

It is what is left to our discretion that helps build entrepreneurs in every generation.

In the next chapter, we share how some enterprising families are creating opportunities for members of the next generation to experience and learn the skills of new beginnings and endings while weighing the risks and returns.

Learning and unlearning. Often leaders are expected to know everything already. This may well be close to the truth in simpler businesses like small family farms, in which methods were passed down over generations and experienced leaders did know a lot more than most other people. And those who have found an industry they love that deeply taps their inner spirit can acquire deep expertise that makes it easy for them to forget they are ever learning something new even while using their wisdom. But in the contemporary world, almost everywhere, things are changing too rapidly for any one person to have all of the necessary knowledge—and indeed, often no one possesses the knowledge because no one yet knows a solution to the problem being addressed. Whether it is parents who must rely on their children to help them learn how to use new technologies such as the personal computer, portable devices, and instant messaging or other social media, or business people who have to bring in educated specialists to determine customer desires, select appropriate equipment, design new processes, or even figure out how to hire qualified, educated specialists, expertise is much more widely distributed than it once was.

Nevertheless, there are often gaps between the perception of leaders and those who are supposed to follow them as to just how much the formal leader is expected to know. Some leaders can try to preserve the image of being all-knowing, invulnerable, settled, superior, or arrived, and this attitude is often fed by followers who perpetuate the expectations. Past success can often cause leaders to overestimate their ability to get it right, making it hard for them to acknowledge that “what got them here won’t get them there.”39 Unlearning the ways of the past, even though they brought success, is perhaps even harder than learning anew, as illustrated by the reactions of two generations of Lumpkins from the Illinois Consolidated Telephone Company mentioned earlier. When Richard Lumpkin went to his father to suggest that they create a holding company so they could branch into the unregulated business, the eighty-five-year old father remarked: “Son, I wouldn’t be for that even if I thought it was a good idea.” While the senior Lumpkin had taken many risks during his sixty-year tenure in the leadership position, at that stage of life he was not prepared to take more overt risks or learn anew. And when most of the spinoffs started by her son in the first five years of his leadership lost money, Richard’s mother said, “I don’t understand why we didn’t just stick with the telephone business,” to which he responded, “I didn’t think we ever left. This is the telephone business. It’s just changed.” To stay a step ahead of the wave, he, his family, and his employees had to be prepared to “unlearn everything we’ve (they) learned in the past 100 years.”40 But such learning and unlearning is a difficult course to master.

We have seen leaders of gigantic corporations and of corner grocery stores caught in the operational everyday trap, leaving little time to think of new undertakings. Yet we are encouraged to see enterprising families like the Scherrers of Switzerland41 that established a plumbing and roofing workshop in 1896 that has grown into a highly successful brand found on most well-known buildings of Zurich. Beat Scherrer, a fourth-generation descendant of the founder, explains that a great part of their family’s success has relied on ensuring the enterprise was always in young hands. For example, he had only worked in his family’s business for five years when his father and uncle handed over the leadership of the enterprise to him. The next generation always gets a shot early on in their business, and thus no one holds on to the top position until death. In fact, although no member of the fifth generation is interested in running the enterprise’s operations, Beat plans to turn over the leadership to nonfamily members next year when he turns sixty and the company celebrates its 120th anniversary.

In conclusion, regardless of which of the ambidexterity skills we consider—awareness of self and surroundings, building a dream and a team, influencing and directing, or new beginnings and endings—continuous learning is necessary. Although it is possible to identify many more competencies that would help entrepreneurial leaders in family businesses, with these they can keep learning and adapting to whatever comes along. In the next chapter we will look at some of the tactics that enterprising families are using to enhance the entrepreneurial leadership skills of each member of their family.

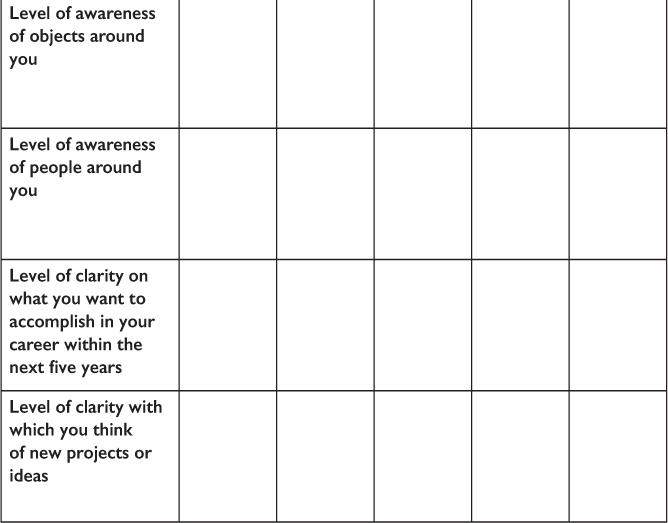

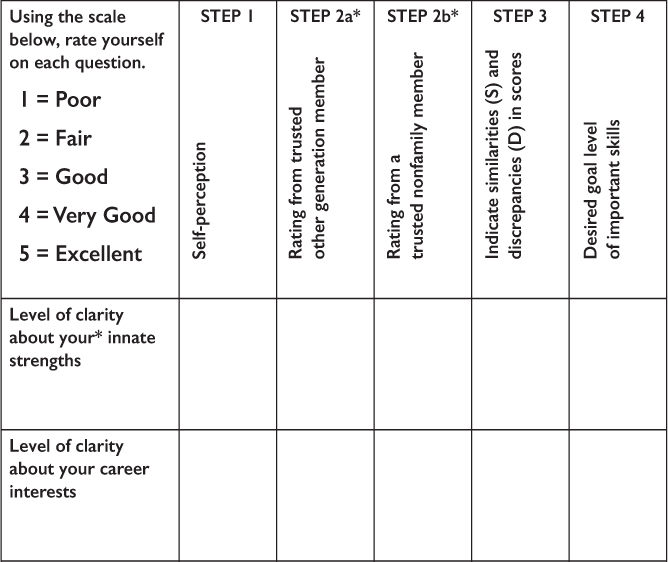

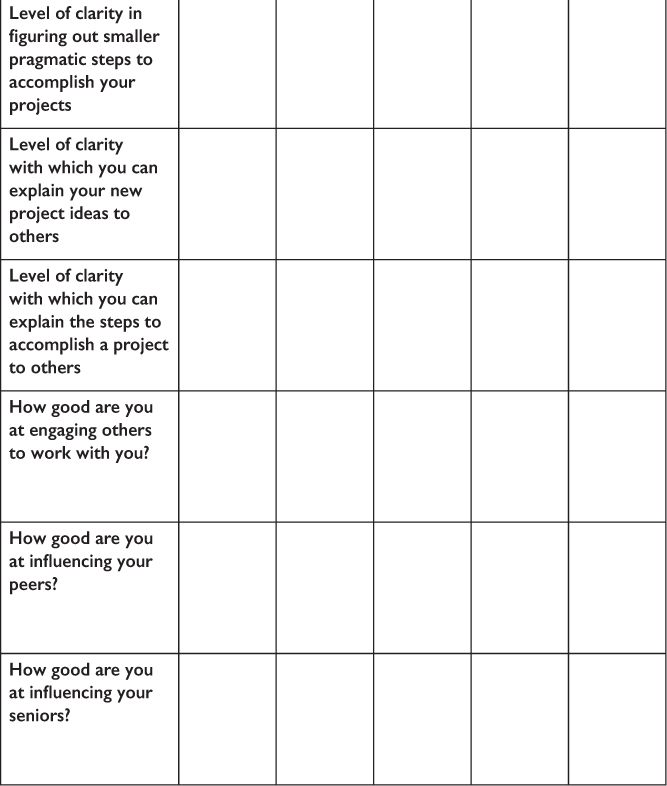

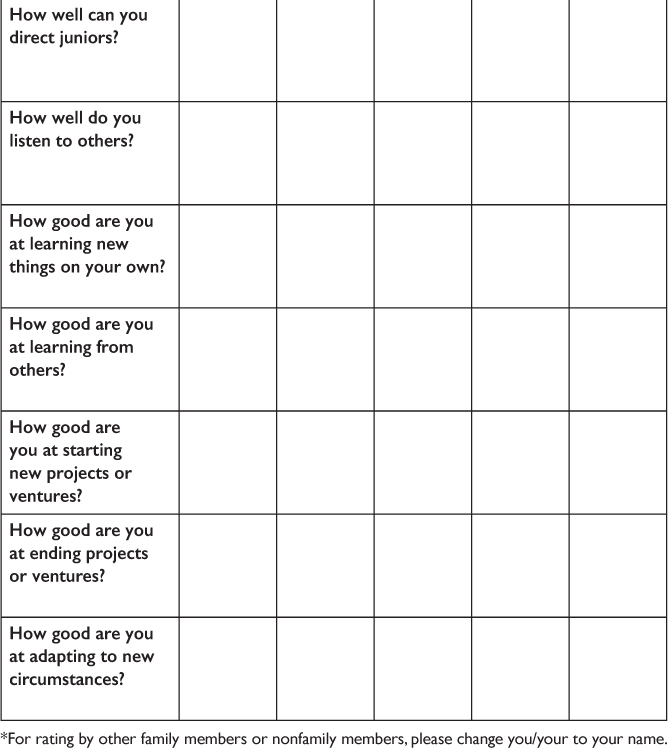

WORK SHEET 1

Entrepreneurial leaders are on a continuous learning cycle working each day to develop ambidextrous skills discussed in this chapter. Use this work sheet to:

1. Rate yourself on the skills listed in the first column in the following table, using a 1 to 5 scale.

2a. Ask a trusted member of the other generation to rate your skills. If you are a member of the junior generation, ask a senior generation member to rate your skill level. If you are a senior generation member, ask a junior to rate your skill level.

2b. Ask a trusted nonfamily member who knows you well to rate your skills.

3. Compare the results in perceptions in Steps 1, 2a, and 2b. Indicate similarities (S) and discrepancies (D) in scores. Discuss the reasons behind these, identifying your strengths and skills that need development.

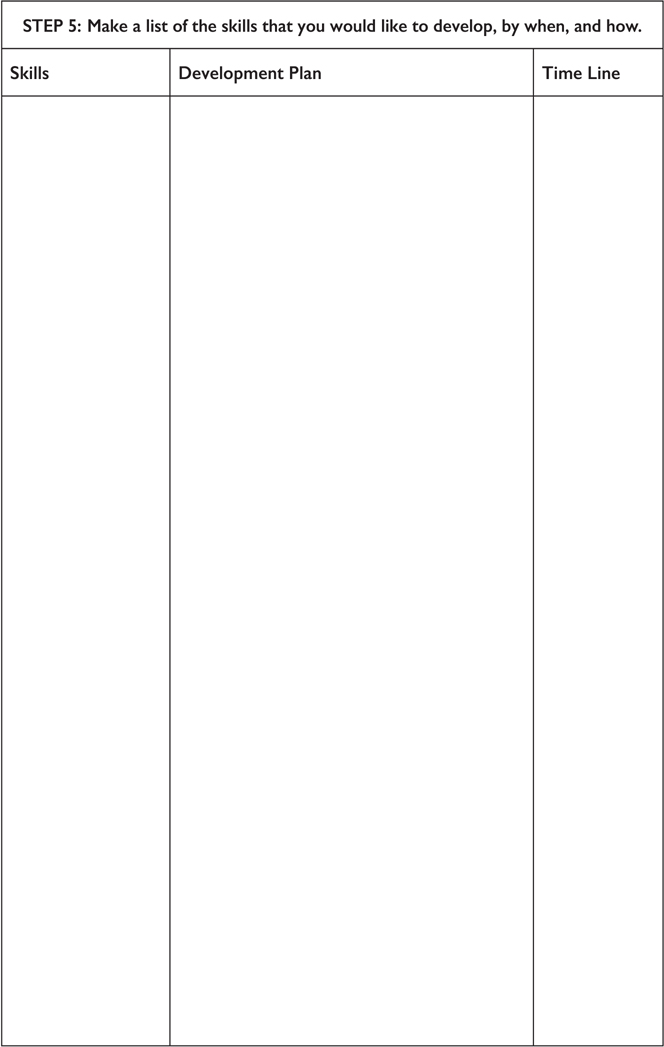

4. Highlight each skill that is important to you and that needs development. Set a measurable goal for yourself.

5. List each skill that needs development. Commit in writing to what you will accomplish, by when, and how.