Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Getting Back to the Table

5 Steps to Reviving Stalled Negotiations

Joshua N. Weiss (Author) | Joshua N. Weiss, PhD (Author)

Publication date: 02/11/2025

When negotiations fail it can be hard to start over. Some people give up, others forget and move on, but the truly successful negotiator learns. Celebrated negotiation thought-leader and member of the UN Negotiations team, Joshua N. Weiss, introduces an evidence-based model for when negotiations stall or fail. Getting Back to the Table explores the reality of failure in negotiation. It lays out the types of failure that can happen, how to cope with it when it does, and how we can be resilient in the face of it. Using Weiss’s easy-to-use framework, readers can successfully get back to the negotiation table. Failing in negotiations is inevitable, but learning and growing from failure is not.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

When negotiations fail it can be hard to start over. Some people give up, others forget and move on, but the truly successful negotiator learns. Celebrated negotiation thought-leader and member of the UN Negotiations team, Joshua N. Weiss, introduces an evidence-based model for when negotiations stall or fail. Getting Back to the Table explores the reality of failure in negotiation. It lays out the types of failure that can happen, how to cope with it when it does, and how we can be resilient in the face of it. Using Weiss’s easy-to-use framework, readers can successfully get back to the negotiation table. Failing in negotiations is inevitable, but learning and growing from failure is not.

Joshua N. Weiss is cofounder of the Global Negotiation Initiative at Harvard, where he also teaches. He is a Senior Fellow of the Harvard Negotiation Project and a senior trainer with William Ury Associates, and he heads his own consultancy, Negotiation Works. He is also on faculty at Bay Path University and has held adjunct faculty positions at ten different universities, including MIT, Harvard, UMass, UC Denver, and American University of Beirut. He is listed as one of the Top 30 Global Gurus for negotiation, and he serves on the United Nations Mediation Team.

Joshua N. Weiss is cofounder of the Global Negotiation Initiative at Harvard, where he also teaches. He is a Senior Fellow of the Harvard Negotiation Project and a senior trainer with William Ury Associates, and he heads his own consultancy, Negotiation Works. He is also on faculty at Bay Path University and has held adjunct faculty positions at ten different universities, including MIT, Harvard, UMass, UC Denver, and American University of Beirut. He is listed as one of the Top 30 Global Gurus for negotiation, and he serves on the United Nations Mediation Team.

1 Negotiation Failures and Their Magnitude

Generally speaking, when it comes to failure in negotiation most people want to know two things: what are the different ways I can fail, and how bad is it going to be? Before we get to those two core questions, let’s briefly define what we mean by failure in this context—even though that may seem obvious to some. For the purposes of this book, failure is defined as not meeting the objective or goal delineated at the outset of the negotiation process.

Now, some people question whether there is such a thing as failure in negotiation, claiming that any failure is merely a setback or a stepping stone on the way to success. I think it’s important to state clearly that I believe negotiation failure is a real thing, although I do sincerely believe that these failures ultimately can lead us to success in the long term, if we manage them properly and learn from them. In my mind, there is absolutely nothing wrong with recognizing a failure for what it is, and indeed it is vital that we do so, so we can cope with it and address it. Facing the cold, hard facts about negotiation failures may not be easy, but it’s important, for a myriad of reasons we will discuss throughout the book.

What happens if we avoid calling not meeting our goal in negotiation a failure? This is an interesting question and one that is worth grappling with briefly. The answer, often, is that we gloss over what happened, and we neglect to be honest with ourselves about what transpired and what we could have done differently. Consider this example. After his team the Milwaukee Bucks—the top seed in the Eastern Conference of the National Basketball Association (NBA) playoffs—lost to the lowest-seeded Miami Heat in the first round in April 2023, a reporter asked star player Giannis Antenakupo if he viewed the season as a failure. Giannis was praised for his answer: “Do you get a promotion every year, in your job? No, right? So, every year you work is a failure? Yes, or no? No. Every year you work, you work toward something, towards a goal, which is to get a promotion, to be able to take care of your family, provide a house for them or take care of your parents. You work towards a goal—it’s not a failure. It’s steps to success. There’s always steps to it. Michael Jordan played 15 years, won six championships. The other nine years was a failure? That’s what you’re telling me?”1

I appreciate the positive outlook, and in the long term, he may well be correct. However, Antenakupo’s inability to own the failure has a downside. Alternatively, he might have stated: “We failed this year. Our goal was to win a championship, and we did not do that. I will say, we learned some important lessons in terms of what it is going to take to win a title, and that is what we are ultimately aiming for in the future.” The difference is subtle, but important. Put differently: Don’t deny failure. Own it.

For most of us, failure in negotiation is something we dread because of the consequences that follow, but it is also something that many of us are only too familiar with from our past experiences. None of us ever sets out to fail, but we subconsciously realize that failures are bound to happen— particularly, as Kennedy reminded us earlier, when we really challenge ourselves to do something new, creative, and difficult. In other words, failure is part of the negotiation terrain, so we’d better get used to it and figure out how best to deal with it and, crucially, learn from it so we can continue to grow and become more effective negotiators.

You might be wondering, can we really isolate the cause of a failure in negotiation when there are so many dynamics at play? From my perspective, the way to approach this question is “Yes, and . . .” What I mean by this is that when we look back at our negotiations where we experienced significant setbacks or failed, we can often identify a primary cause. Of course, it is also important to account for secondary causes, or exacerbating factors, that may have played a role as well. These are not the essence of the problem, but they will have added to the challenge and made it that much more difficult to deal with. With this in mind, let’s delve into the categories of failure and their magnitude.

Categories of Failure

In my experience as a negotiator, I have identified seven primary types of negotiation failure. While I do not pretend that this is an exhaustive or definitive list, it can provide a useful framework for analysis. As you read through this list, think about your own experiences with failure and which of these categories they might fit into.

1. Take a Crack at It Failure

When the negotiation challenge is very difficult, but you try anyway and expect to fail in the short term

This type of failure is the least problematic; it occurs when we know that failure is actually more likely than success in the short term, but there’s a strong opportunity to learn from the experience. This is often the case when we are trying to push the envelope or looking for a breakthrough when faced with a very difficult negotiation issue.2

We most commonly see this type of failure when it comes to negotiating internally about the development of new and innovative products—some of which may have a significant societal impact. The story of Steve Jobs and the iPhone fits this description. According to Brian Merchant, author of the book The One Device: The Secret History of the iPhone, Apple’s founder, Jobs, was initially very reluctant to develop the product. The engineers knew they had something good, but they had to convince Jobs first. As Merchant describes it, “They knew there was a right way to approach Jobs with this stuff and there was a wrong way, and you had to, sort of very strategically roll it out and give it to the right person to give it to him on the right day when he was in the right mood.”3 They found their intermediary in Apple’s design chief, Jonathan Ive. Ive said to the team, “Let me bring it to Jobs when he is in a good mood, when, you know, the time is right.”

Ive was one of Jobs’ closest friends, but when he unveiled the project and attempted to negotiate to produce a prototype, Jobs wasn’t impressed; according to Merchant, he simply “said ‘Meh.’ And, just kind of, you know, wrote the idea off.” The engineers, however, were persistent, going through tests and failures and more tests and more failures until they got the new touchscreen technology just right. Then they brought it back to Jobs to negotiate with him again. Merchant summarizes the interaction this way: “Sure enough, Jobs came around. He thought about it some more. He asked to see the demo again and he said, ‘OK, this is pretty cool.’ And then fast forward a couple weeks, couple months and he loves it. And now he is like, ‘Oh, you know what? Multi-touch? Yeah, I invented that.’”4 In this case, the engineering team knew at the outset that this type of failure in their negotiations was part of the process and recognized that they would likely have to negotiate many times with Jobs before he might say yes.

2. Slipping Through Our Fingers Failure

Not reaching agreement when it is eminently possible

The next type of failure is called the Slipping Through Our Fingers failure. Why? Because when something slips through our fingers, it was within our grasp, and, somehow, we let it slip away. In other words, we did not reach an agreement that was achievable and would have met the parties’ respective interests and needs when it was very possible to do so.

Let me explain why I include these two caveats. With regard to the first one, there are many instances where a possible deal is on the table, but for one reason or another it is not achievable. For example, what one party is asking of the other may simply not be possible, or the timing might not be right, causing negotiations to stall or parties to come to the table in bad faith, or the resources to make a deal work might not exist.

Regarding the second proviso, it’s important to keep in mind that the purpose of negotiation is not simply to reach an agreement; it is to meet our goals and needs as best as possible. If a possible deal is on the table but for some reason is not achieved, it only qualifies as a failure if that deal would have met our objectives. (If we reach an agreement that doesn’t satisfy our underlying interests, that’s another form of failure, which we’ll look at next.)

Let’s consider an example that illustrates this type of failure. Jon Lester was a Major League Baseball player for the Boston Red Sox. After being drafted, he made his way to the team in summer 2006. Tragically, in September of that same year Lester was diagnosed with anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Fortunately for Lester, this form of high-grade lymphoma typically has a favorable clinical course—as it ultimately did for him. The Red Sox stood by him and his family through this arduous and trying journey. In 2007, he was back pitching for the Red Sox and was integral to the team winning the World Series.

Fast-forward to January 2014, when Lester was to become a free agent the following season. He emphatically stated at the time, “These guys are my No. 1 priority . . . I want to be here until they have to rip this jersey off my back.”5 Lester added that he expected to get a lower offer to sign an extension with the Red Sox than he might get elsewhere, and that he was willing to take the hit. In his words, “I understand that you’re going to take a discount to stay. Do I want to do that? Absolutely.” He finished by uttering, “But just like they want it to be fair for them, I want it to be fair for me and my family.” And that is where the negotiation problem began.

The Red Sox made Lester what they likely considered an “initial offer to get the conversation started”—a four-year, $70 million proposal. Arguably, the market or industry standard for Lester, when looking at comparable pitchers, was more along the lines of five to six years and between $120 and $150 million. Unbeknownst to Lester, the Red Sox were willing to up their offer (eventually raising it to six years and $135 million), but by that time the damage had been done due to the comparatively low early sum. Despite Lester’s previous comments about his deep desire to stay in Boston and his willingness to be flexible around the compensation, a negative tone to the negotiation had been set. Both sides expressed a desire to reach a deal, but Lester ultimately ceased negotiations, subsequently asking for, and being granted, a trade to the Oakland Athletics. A year later, he ended up signing a long-term deal with the Chicago Cubs.6

This negotiation is a classic example of two parties who had all the makings of an achievable deal, a mutually expressed desire to reach said deal, and other positive dynamics going for them, only to have an agreement slip through their fingers due to multiple factors that, in hindsight, could have been avoided. There is no way to see this process as anything but a failure for both sides.

3. What Were You Thinking Failure

Not meeting one’s negotiation objectives/interests

As was previously mentioned, the goal of negotiation is not necessarily just to reach an agreement, but rather for negotiators to meet their objectives and interests as best as possible. Many agreements that are reached fail to meet a negotiator’s objectives and, therefore, should be considered failures. In these cases it’s fair to ask, “What you were thinking by agreeing to that?” Here is an illustrative case of such a failure.

Maureen worked in sales at Adchips Inc. and was only a few years out of college. She desperately wanted to succeed in her position, which she hoped would serve as a stepping stone to the rest of her career. Maureen’s job was to sell microchips to large companies that used them in their technology-related products. One such company was Teradon, a leader in the industry and an organization Adchips had worked with for some time.

Our story begins when Maureen and her counterpart, Michael, met to engage in a negotiation to renew Teradon’s previous contract. Michael had previously dealt with another Adchips salesperson, but that person had recently left to take a position at a different company. Sensing that Maureen was relatively new and a bit inexperienced, Michael asked her for a sizable order of microchips. The order exceeded her goals—but this would come at a cost. He explained that he wanted a 20% discount, given the size of the order and as a reward for the many years Teradon had used Adchips’ chips.

Maureen was taken aback by the initial offer. The quantity was fantastic, but by her quick calculations the discount would make this a small downer for her company. Instead of stepping away to consider the deal or making a counteroffer, she negotiated with herself, rationalizing that the former consideration outweighed the latter and that she would be able to explain this to her boss. She agreed to Michael’s terms.

After preliminarily signing off on the deal, she took it back to her boss, nervously hoping for approval. Despite giving up a significant percentage to close the deal, she was very excited about the size of the order. Her boss reviewed the agreement and was shocked that Maureen had already signed off on the deal. After running the numbers comprehensively, she showed Maureen how the agreement was even more of a downer for the company than she’d anticipated, due to a lack of inflationary clauses over the life of the four-year contract. Maureen’s boss finished the conversation by stating, “What were you thinking? I’m sorry, but this deal is unacceptable. We have to fix this, and it’s going to take some serious work.” Maureen, feeling humiliated, admitted that she had made a mistake in the calculations and now realized that the agreement did not meet the company’s underlying interests and would set it back quite a bit.

In this negotiation, Maureen was able to reach an agreement, but she did not meet her or her company’s financial objectives in doing so. As such, this was a failed negotiation that she would have been better off not concluding with an agreement.

4. Penny-Wise and Pound-Foolish Failure

Reaching an agreement that damages the relationship

Some agreements are created in such a manner that they achieve the tangible objective—say, agreeing on a monetary amount—but in doing so they damage the relationship between the parties. The reason this type of failure is called Penny-Wise and Pound-Foolish is because a negotiator who is penny-wise tries to save a small amount in the short term at the expense of the long term. While money is often part of the equation, in this context it is really about emphasizing the short-term gain over the longer-term relationship. Since effective negotiation most often relies on strong relationships, particularly when negotiating with the same person or organization time and again, this form of failure can have lasting consequences.7

Here is an archetypal example. A number of years ago, I purchased a used car from a dealership while trading in an older vehicle. I had already bought two cars from this dealer in the past and used them to service my vehicles, so we had developed a solid relationship over time. I was pleased with the deal, except for one thing: the car’s tires were quite worn and needed to be replaced. I pointed this out to the salesperson, who said he understood my concern. He then explained that the dealership was running a promotion: with all pre-owned car purchases, new tires would be provided to anyone free of charge within the first year. “Just schedule a time with our service department in the coming weeks,” he said, “and they’ll take care of it.” This seemed reasonable to me, and my previous experiences with the dealership had been positive, so I agreed. Fast-forward a week, and I called to set up a time to have the tires replaced. When I did so, I sought to reaffirm the arrangement so there were no surprises. That’s when the difficulties began.

The service technician explained that they had no such deal in their system and could not grant me that arrangement. I asked to be transferred to the salesperson I had worked with. When I got him on the phone, I recounted my experience to him, and he denied ever telling me about the tire deal. We went back and forth, with me pressing him on whether he recalled the conversation and him saying vaguely that he did remember discussing the issue, but he refused to admit to ever having stated anything about a tire deal. I acknowledged that some form of misunderstanding must have occurred and asked if there was anything they were willing to do, given that I had been a very good customer over the years. He said they were willing to give me a 10% discount on the tires to rectify things. Needless to say, I was not really satisfied with that and countered by asking for a 50% discount, which felt fair to me and a seemed like a reasonable split at this juncture. He was not willing to budge.

At this point I’d become very frustrated, and I asked to speak to the general manager at the dealership. When I got the manager on the phone—someone I had not dealt with in the past—I explained my history with the dealership and the current situation. He was empathetic but stated that the salesperson should not have made any such offer. I admitted that it was quite possible there had been some miscommunication, but expressed that I was deeply disappointed with how they were handling this and that I hoped they would live up to the commitment made regarding the tires, or at least share half of the burden. The manager said they would not do anything beyond offering the 10% discount the salesperson had proposed. I remarked that I had been a good customer over the years and explained that this decision would permanently damage our relationship. He accepted that this was a possibility, but said it was something he was willing to live with. I was seriously disappointed; I felt that the experience was unjust and that there was no respect for the customer relationship. In the end, not only did I stop doing business with the dealership, but I shared my experience with others more broadly and even discussed their practices with the state.

In this example, we see a deal that was done that seemed to work for everyone, but when a commitment was made and not kept it ended up permanently damaging the relationship. The dealer opted to focus on the short term and saving some money, rather than the longer term and losing a good customer. This negotiation was clearly a failure for both parties: I did not get the free new tires promised to me and had to pay to replace them, and the dealership lost a valuable customer (and maybe others) as a result of how they handled the negotiation.

5. Bad Agreement Failure

Reaching a bad agreement that is worse than your BATNA (walkaway alternative)8

Many agreements that are reached are, simply put, bad, and should never have been consummated. For example, perhaps they don’t serve one or both parties’ underlying interests, or they miss out on value that could expand the pie, or a deal is reached that is worse than a party’s walkaway alternative (aka Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement, or BATNA). Often negotiators reach these types of agreements because they have not done careful preparation, or they feel pressured. Whatever the cause, it is not uncommon for such agreements to fall apart shortly after the ink is dry.

Think about this example, where a lack of preparation and sufficient information led to a series of bad deals that were much worse than the party’s BATNA. Brian Epstein grew up in Liverpool, England. His father was a furniture salesman. Epstein first saw the Beatles play in November 1961. At the time, he was running a record store in Liverpool. The story goes that several customers came into his store asking for a single the Beatles had recorded in Germany. Thinking there might be something to this band, he went over to the Cavern Club at lunchtime one day to see for himself. Of course, he was blown away by what he saw. He returned to the club every day for the next three weeks, then approached the band about being their manager.

In January 1962 Epstein and the Beatles signed their first management contract. Epstein negotiated to receive 25% of the Beatles’ earnings, which was a very high percentage for his services. As John Lennon later said, “He wanted to manage us and we had nobody better, so we said, ‘All right, you can do it.’”9 Initially, it seemed to the band that the 25% cut was well worth it. Epstein secured them a deal with George Martin at EMI, he helped bring Ringo Starr into the band, and he helped them remake their sound so that their music resonated with mainstream audiences, first in the UK and then around the world.

Then, problems from a negotiation point of view began to emerge and proliferate. Many of the issues had to do with the fact that Epstein failed to adequately prepare and did not know the ins and outs of the music industry and the standards involved. As he openly stated at the time, “I have no musical knowledge, nor do I know very much about show business or the record business. The Beatles are famous because they are good. It was not my managerial cunning.”10 The first deal Epstein negotiated that can only be characterized as an abject failure had to do with the original EMI contract signed with George Martin. This contract gave the Beatles just one penny for every record sold . . . and that penny was split between them! What’s more, the royalty rate was reduced for sales outside the UK: the band received just half a penny per single, again split four ways.

While there were a series of other negotiation failures led by Epstein, one that stands out for a clear lack of preparation had to do with the contract he signed on the Beatles’ behalf when they filmed the movie A Hard Day’s Night in 1964. According to sources that represented the studio at the time, they were determined to allow no more than 25% of the profits to go to the Beatles. Epstein walked into the negotiation and assertively declared: “I think you should know that the boys and I will not settle for anything less than 7.5 per cent.”11 The studio readily agreed, and the Beatles were out vast sums of money.

By any measure these were bad deals for the Beatles, but they were even worse when you consider the industry standard and the level of fame the band was quickly achieving. They had a tremendous amount of negotiation leverage to wield, but Epstein failed to meet those possible realities due a lack of knowledge of the music business and negotiation acumen, and a failure to adequately prepare.

6. Emotionally Unintelligent Failure

When emotions are not managed effectively, and the process collapses as a result

Emotions are an age-old challenge for any negotiator. Emotions will always play a role in negotiation, and they can do so in a productive manner if they are brought into the process with some control. But if emotions are not managed effectively, they usually overwhelm negotiators, often leading to an escalation in tension and ultimately a collapse of the process.

A colleague shared with me the following story about a physician who was very famous for doing organ transplants in his country. He had a unique challenge in that he worked part time at a university teaching and research hospital, and part time in private practice. This led to occasional conflicts arising with his university hospital colleagues (including an undertone of jealousy), as well as a possible conflict of interest between his two roles. For example, when an organ became available, how would it be determined who the recipient should be—patients at the university hospital or at his private practice—and, equally importantly, who would get to decide?

The two sides recognized the problem and agreed to come together to try to work out a solution to the issue. Initially, the doctor and his colleagues failed to make noticeable progress, so they brought in a third party to assist them by guiding the process. According to the doctors, this proved to be very helpful, and the parties made considerable strides toward an agreement. They carved out the main parameters, leaving some details to be finalized. One of the most important details to be addressed was when the agreement would take effect. The doctor explained that he would need about 30 days to get the new processes set up in his private practice. The other side agreed to these terms, and the doctor stated that he was prepared to sign.

But just prior to signing, the lawyer for the other doctors, who had been rather hard-nosed throughout the process, asked if he could meet privately with his clients. When they came back to the table, the lawyer explained that they wanted the deal to go into effect in two days. He did not explain why, and refused to share any further information about his clients’ reasoning. The doctor was deeply insulted. He stood up, tore up the agreement, explained that what they would have in two days was his resignation, and stormed out of the room. A promising process came to a crashing end.

There are different possible explanations for what caused this failure, but my colleague was clear that uncontrolled emotions had played a large role and ultimately doomed this process. The doctor who stormed out had felt that this final interaction carried a strong odor of distrust. Understandably, he was offended by the last-minute change and lack of explanation, which indicated to him a deep undertone of disrespect.

7. Under the Table Failure

When the parties fail to notice a hidden dynamic or intangible aspect driving the negotiation

In many negotiations, there are often various hidden dynamics and intangible aspects that hinge on a lack of information. These variables, which I like to say live under the negotiation table and out of initial sight, can often be the cause of failure. Much of the time this happens because negotiators don’t know to look for them, or miss clues that these “under the surface” elements are what are really driving the negotiation. So, they focus their efforts elsewhere and miss dealing with the essence of the challenge. The following is a very good example of this type of problem and how it can cause a failure in the process.

There was a beautiful hotel situated right on the coast in South Africa. The hotel was part of a bundle of properties and businesses owned by the Dube family. The family had two children, Caroline and Martin, who became involved in the business as they got older. Caroline studied and practiced law and brought that skill set to the family business. Her younger brother, Martin, was a rather weaker character, lacking direction and ending up with a drug problem in his youth. He ultimately overcame this, but the process inflicted much pain and anguish on the family and affected their view of his competence.

After sorting out his life and getting married, Martin sought to take his place in the business. However, bad blood simmered under the surface between the siblings, related to their past interactions. This was exacerbated by their respective spouses, who each had little trust in their brother- and sister-in-law and made that clear to their partners.

Their father, John, ultimately decided to give Martin and his wife a try at running the hotel. Encouragingly, they ran the operation quite well. After some time and positive results, Martin began to demand more independence. In fact, he went so far as to say, “I want to move out from under the guise of the family business, and we would like to have the hotel as our own.” Martin’s proposal to his father was that he sell it to them on very favorable terms. It was at this point that the situation escalated, with Caroline stepping in and saying that she did not want this to happen because the hotel was the crown jewel of the family business. John agreed with Caroline, as did John’s wife, Eleanor. John’s counterproposal was that the hotel would remain part of the family business, but that Martin and his wife would continue to run it and be given a larger stake in the business, eventually becoming 10% shareholders. Martin rejected the offer, and the family was at an impasse.

It was this point that the family brought in a third party, Allan, to try to help them negotiate a solution. Both Caroline and Martin said they didn’t want their spouses involved in the formal process, and Allan agreed to their wishes. This, however, turned out to be a big mistake, because the spouses, through their behind-the-scenes influence on Caroline and Martin, held the key to reaching an agreement. It was that hidden dimension, and the underlying intangible feelings of mistrust and disdain, that caused the family’s negotiations to fail. This failure resulted in irreparable damage, with the family remaining badly divided long into the future.

Again, while this is not necessarily an exhaustive list, I consider this a decent overview of the different types of failures that can occur in negotiation. But there’s one final dimension to discuss—namely, the magnitude. In other words, exactly how bad was the failure?

Magnitudes of Failure

As we all know, when we negotiate there are bumps in the road. But are those bumps mere potholes that we can fill in and get through with some persistence, or are they more severe, where the entire road needs ripping up and repaving? There is clearly a big difference, which corresponds to the magnitude of the failure we are experiencing in our negotiation. This is something that must be determined as part of the analysis of failure. For example, did the parties set out to explore a difficult negotiation knowing they were unlikely to succeed in this process, but hoping they might learn something that would ultimately help them meet their objectives in the future? Or was the failure a temporary setback, with the parties likely to revive talks in the near future? Or did it go well beyond that, into the realm of a catastrophe that forever destroyed the relationship between the parties and any hope of a successful negotiation? Severity is a continuum, so all of these outcomes (and more) are possible.

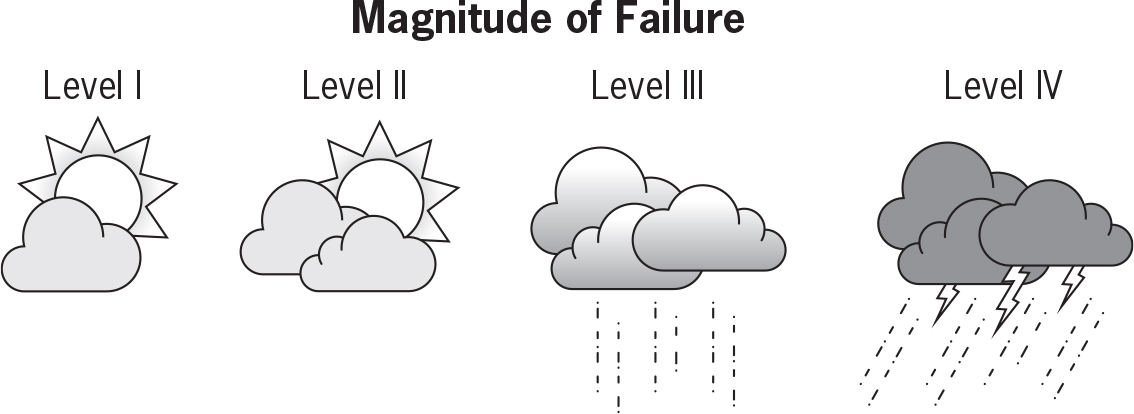

To help us understand the nature and seriousness of the failure we are experiencing, I have created a four-level magnitude scale (Figure 1-1) that can help us determine whether it is worth our time and effort to try to revive a specific negotiation or come back to the table and attempt a new negotiation after some time has passed. In most cases the answer will be yes, we should try very hard to get back to the table, but there may be some instances where we have to recognize that the failure we’ve experienced is beyond repair.

Level I: Intelligent Failure

This first level borrows the concept of intelligent failure from Sim Sitkin, who coined the term in his paper “Learning Through Failure: The Strategy of Small Losses.”12 Sitkin defined intelligent failures as failures that are somewhat expected, due to the uncertainty of the process and the desire to push the envelope and see what happens, engaging in purposeful exploration that advances an idea or concept. It is anticipated that failure will happen and lead to the next process and potential breakthroughs. In particularly challenging negotiations, we often experience this type of failure because the process itself is an exploration of what is possible. If a process fails—even when creative thinking is involved—and there is something to be learned for future processes, or seeds are planted for the next round of talks, we are working in the realm of intelligent failure and at Level I on our scale. At this level, failure is not necessarily seen as a negative thing.

FIGURE 1-1. How bad is it?

Level II: Temporary Setback

A failure at this level is the least significant type of negative failure. It manifests itself in the form of a temporary setback or the breakdown of a process, but definitely not a collapse. With this type of failure there is usually a relatively clear path back to the table; the deal still generally makes sense for the parties involved, and it is likely that they will reengage at some point in the near future. Many negotiators view failure through this lens, and it does represent a good majority of failed negotiation processes. It is not uncommon for parties to reach a stalemate or deadlock and decide that a deal won’t work or there is no way forward, only to come back to the table a bit later with a new idea or a different angle.

Level III: Breakdown

Level III is a more severe form of failure, where there is a lot of uncertainty about what will happen going forward. A Level III failure is characterized by a significant breakdown in the negotiation process, with the failure leading to the strong possibility that the process will not continue. It is possible for the talks to resume, but it will take a lot of work, mutual desire to restart the process, and creative thinking on both sides to make it happen. Whether this can happen depends on several factors, including the damage done to the relationship, the nature of the parties’ respective BATNAs, and dynamics such as the power asymmetry between the parties, deadlines, and time pressure.

Level IV: Catastrophic Failure

Level IV failures are the most severe type. These are catastrophic scenarios where the process entirely collapses, the relationship between the parties is severely (and likely irreparably) damaged, and another effort to negotiate is highly unlikely unless something dramatic happens. This kind of failure is typically the hardest to come to grips with, because it means an almost certain end to any kind of negotiation process. Perhaps one day, after wounds heal and significant time passes, there can be another attempt at reviving talks, but not in the foreseeable future.