Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Leading with Character and Competence

Moving Beyond Title, Position, and Authority

Timothy R. Clark (Author)

Publication date: 09/15/2016

Moving beyond Title, Position, and Authority

“Leadership is an applied discipline, not a foamy concept to muse about,” says three-time CEO, Oxford-trained scholar, and consultant Timothy R. Clark. “In fact, it's the most important applied discipline in the world.” The success of any organization can be traced directly to leadership. And leadership can be learned. But too many books and development programs focus exclusively on skills.

In reality, performance and ultimate credibility are based on a combination of character and competence. As Clark puts it, character is the core and competence the crust. He shows how greatness emerges from a powerful combination of the two, although in the end character is more important. A leader with character but no competence will be ineffective, while a leader with competence but no character is dangerous.

Clark spotlights the four most important components of character and competence and offers a series of eloquent, inspiring, and actionable reflections on what's needed to build each one. Fundamentally, he sees leadership as influence—leaders influence people “to climb, stretch, and become.” You need character to influence positively and competence to influence effectively.

This is a book for anyone, no matter where he or she is on the organization chart. Because today employees at all levels are being asked to step up, not only can everyone be a leader, everyone has to be. Clark's insights are profound, and his passion is infectious. “Leadership” he writes, “is the most engaging, inspiring, and deeply satisfying activity known to humankind. Through leadership we have the opportunity to progress, overcome adversity, change lives, and bless the race.”

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Moving beyond Title, Position, and Authority

“Leadership is an applied discipline, not a foamy concept to muse about,” says three-time CEO, Oxford-trained scholar, and consultant Timothy R. Clark. “In fact, it's the most important applied discipline in the world.” The success of any organization can be traced directly to leadership. And leadership can be learned. But too many books and development programs focus exclusively on skills.

In reality, performance and ultimate credibility are based on a combination of character and competence. As Clark puts it, character is the core and competence the crust. He shows how greatness emerges from a powerful combination of the two, although in the end character is more important. A leader with character but no competence will be ineffective, while a leader with competence but no character is dangerous.

Clark spotlights the four most important components of character and competence and offers a series of eloquent, inspiring, and actionable reflections on what's needed to build each one. Fundamentally, he sees leadership as influence—leaders influence people “to climb, stretch, and become.” You need character to influence positively and competence to influence effectively.

This is a book for anyone, no matter where he or she is on the organization chart. Because today employees at all levels are being asked to step up, not only can everyone be a leader, everyone has to be. Clark's insights are profound, and his passion is infectious. “Leadership” he writes, “is the most engaging, inspiring, and deeply satisfying activity known to humankind. Through leadership we have the opportunity to progress, overcome adversity, change lives, and bless the race.”

—Dave Ulrich, Rensis Likert Professor of Business Administration, University of Michigan, and Partner, The RBL Group

“This book will be the cornerstone of MBA programs and leadership training. It is packed full of practical real-world examples from the production floor to the chaotic decision-making dens of CEOs.”

—Michael Goold, EdD, Chief of Police, Rancho Cordova, California

“This book provides new and seasoned leaders with practical tools for leadership development. It's a great reference that offers fresh insight combined with compelling stories. You will find breakthrough concepts and ideas that you can put to work right away.”

—Murray Manzione, Director, Leadership and Professional Development, NVR

“As a high school calculus teacher, I honestly did not see how this book would apply to me personally. I love teaching, and I don't have aspirations of becoming a principal. However, Timothy Clark's description of a true leader is what every devoted and caring teacher is striving to become! If all teachers were to genuinely put into practice the ideals described by Clark, the learning environment in classrooms across the country would change dramatically.”

—Craig B. Smith, calculus teacher, Lone Peak High School

“I have known Tim for nearly twenty years. He never ceases to amaze me with his ability to synthesize and inspire. This book offers powerful guidance for leaders. I am eager to apply what he teaches.”

—Eric L. Denna, Chief Information Officer, University of Maryland

“Tim's book challenges us to have the courage to consistently model true leadership. As a parent, I think the most important place to get it right is at home.”

—Libby Macomber, Partner, Advantage Performance Group, and mother of teenagers

CHAPTER 1

The First Cornerstone of Character: Integrity

I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and incur my own abhorrence.

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895)

African-American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman

The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845)

Our Integrity Problem

The first cornerstone of character is integrity—but let’s not get philosophical about what that means. We are talking about basic, straight-up honesty. Unfortunately, corruption is the pandemic of our time.1 Most nations on planet Earth are deeply and almost irretrievably corrupt. They have become undrainable swamps. Greek philosopher Aristotle said, “The mass of citizens is less corruptible than the few.”2 For the sake of civil society, we need that to be true. Yet according to the Edelman Trust Barometer, three out of four institutions globally are losing the public’s trust.3

Consider that in this country we are chasing after dreamy egalitarianism with fiscal recklessness. We like rights and dislike responsibility. With our no-fault philosophy, we suffer from the tyranny of tolerance. We have adopted a spray-on-tan culture of YOLO narcissism. Indeed, if we can clear the decks of right and wrong—disavow, repudiate, and savage the concepts—we can give ourselves permission to do anything we want.4 And if we want to sound erudite about it, we call morality “cultural relativism.”5 As one observer said, “As truth has been relativized—absolutely relativized, so to speak—so has morality.”6

We have a hard time being honest about the problem. We would rather extend our adolescent play of the mind. The truth is that our compass-free society is immoral in its feigned attempts to be amoral. As political thinker and historian Alexis de Tocqueville said of the Old World, we can say of the new: We are “untroubled by those muddled and incoherent concepts of good and evil.”7

The Broken Triangle

We all come with a preinstalled moral sense, yet we still need to be taught integrity because it requires skill and vigilance to maintain it. We learn integrity by seeing it in action. Our children have to learn it the same way. Regrettably, as a society we are not teaching and modeling integrity to the next generation as we should. Religiosity has waned, and most schools are mandated by law to play neutral. If we yield to this “wintry piece of fact,”8we have to admit that the three institutions of home, church, and school—these agents that represented the triangle of socialization and have for centuries carried the burden of imbuing the next generation with integrity—are broken. This largely explains our demoralization, which is a predictable consequence of our willingness to embrace the delusion of amorality, or permissiveness thinly disguised.9

With the triangle of socialization broken, we have, as political scientist James Q. Wilson asserts, amputated our public discourse on morality at the knees.10 And the predatory media is happy to step in as a surrogate to teach secular humanism and its popular corruptions—namely, the norms of gain and glory, indulgence, self-aggrandizement, and a hundred forms of venality. Not surprisingly, many of society’s young think that integrity is unrealistic and perhaps even quaint. They may discount it as Disney idealism because they have been taught that a serious person plays to win.11 Indeed, ours has become a cowardly culture in which everyone forbids everyone to make value judgments.12

You Will Be Tested

On one occasion I was training leaders at a Fortune 500 corporation. I brought a large for sale sign into the room, the kind you would plant in your front yard. I gave it to one of the leaders and asked, “Are you for sale?” Then I paused and said, “If you don’t have an ethical creed that goes to your marrow and says, ‘some things are not for sale at any price,’ you are for sale. You will go to the highest bidder.”

Through the course of your personal and professional life, you will run an ethical gauntlet. Your integrity will be tested. You will be propositioned to lie, steal, cheat, extort, bribe, indulge, silence, swindle, defraud, scam, evade, and exploit. Even if you don’t go looking, the opportunities for ethical misconduct will find you. At the very least, you will be asked to remain purse-lipped and silent as you witness soft forms of crooked behavior around you.

Anticipate the obstacles. Prepare for their arrival. When an ethical dilemma presents itself in the moment, the situation suddenly becomes pressurized. Negotiators call it “deal heat.” Be ready for that dialed-up intensity. And be alert because ethical issues do not announce themselves. Howard Winkler, manager of ethics and compliance at Southern Company, said, “When an ethical issue arises, it does not come gift-wrapped with a note that says, ‘This is an ethical issue. Prepare to make an ethical decision.’ It just comes across as another business problem that needs to be solved.”13

Know too that at least once in your life you will face a monumental obstacle, a severe trial, a crucible affliction that will try your integrity to the breaking point. You may well experience, as writer Victor Hugo said of his character Jean Valjean in Les Miserables, “the pressure of disproportionate misfortune.”14That day comes for all of us when our integrity goes on trial. It came for Sir Walter Scott, the beloved Scottish writer, when his publishing house failed and he found himself buried under crushing debt. In his personal journal, he described it this way: “Yet God knows, I am at sea in the dark, and the vessel leaky.”15

Do You Have a Personal Magna Carta?

Albert Schweitzer, the great humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize winner, studied ethics and said the experience “left me dangling in midair.”16Ethics, which is a branch of philosophy, likes to ruminate about what is right and wrong, but it steadfastly refuses to tell you what to do. Don’t worry, you can’t read your way to integrity, anyway.

Yes, we face some very complex ethical issues in our day. But most of the time, acting with integrity is not about knowing what to do; it’s simply about doing it. The ability to perform moral reasoning does not make you moral; it’s doing what is moral that makes you moral. For example, in a recent survey in the United Kingdom, students were asked, “Would you cheat in an exam if you knew you wouldn’t get caught?” Fifty-nine percent of those surveyed said, “Yeah, sure,” while only 41 percent said, “No way.”17Do these students lack moral-reasoning skills?

As a human being, you confront moral choices that test your integrity. Leaders with integrity govern themselves. They regulate their own behavior and impose their own limits. They do not lie, steal, or cheat because they know it’s inherently wrong. They have a personal Magna Carta to stand on principle.18 People flock to their high standards and taproot convictions.

But if you are unsworn to principles, integrity vanishes. As professor Harvey Mansfield wrote, “When choice is without any principle to guide it, those who must make a choice look around for something to replace principle.”19 That search will often come back to the pursuit of selfish interest. If you don’t stand for principle, there is simply nothing left to stand on. You will accept the unprincipled gain and reject the principled loss.

Leaders without integrity must be regulated from the outside by rules, laws, compliance systems, organs of restraint, and the larger control environment around them. They also know innately that lying, stealing, and cheating are wrong. They know the principle but refuse to be governed by it. Surely you have seen how people behave in riots. As the risk/reward ratio shifts, as the deterrence and the threat of punishment disappear, people burn cars and loot the neighborhood store. There’s no internal check on behavior. It’s a base and primal response.

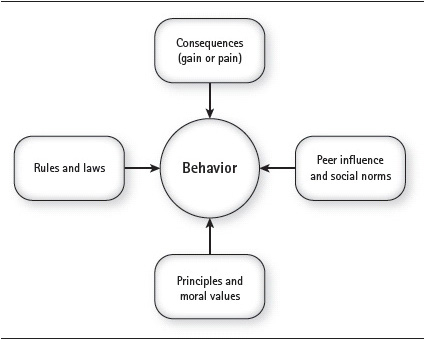

The Four Moral Navigators diagram shows how people make moral decisions, using four devices that have an impact on their behavior (see figure 1.1).

Consequences (gain or pain). With this navigator we attempt to think through a course of action and its consequences. We forecast the pain or gain associated with a given choice. If the reward is high and the risk is low, we move toward the reward.

Consequences (gain or pain). With this navigator we attempt to think through a course of action and its consequences. We forecast the pain or gain associated with a given choice. If the reward is high and the risk is low, we move toward the reward.

Rules and laws. With this navigator we look for rules and laws that apply to a given course of action and allow ourselves to be governed by them.

Rules and laws. With this navigator we look for rules and laws that apply to a given course of action and allow ourselves to be governed by them.

Peer influence and social norms. With this navigator we are guided by the influence of those around us. We sense and follow the norms, mores, and expectations of society or the organization to which we belong.

Peer influence and social norms. With this navigator we are guided by the influence of those around us. We sense and follow the norms, mores, and expectations of society or the organization to which we belong.

Figure 1.1 The Four Moral Navigators

Principles and moral values. With this navigator we consult and follow principles and moral values implanted in our hearts and minds. We act out of a conviction of what is right or wrong, regardless of outside pressure, influence, or temptation.

Principles and moral values. With this navigator we consult and follow principles and moral values implanted in our hearts and minds. We act out of a conviction of what is right or wrong, regardless of outside pressure, influence, or temptation.

Each device is important and has a role to play, but to maintain integrity, principles and moral values must have the last word. The person or organization without integrity suspends principles and moral values while applying the other navigational devices. For example, why did Volkswagen executives decide to manipulate their diesel engine software to control emissions only during laboratory testing but not in real-world driving? They applied the first device—consequences—and suspended the other three. They were lured by the prospect of financial gain.

Integrity must be rooted in your understanding of leadership: Leaders with integrity lead to contribute. Leaders without integrity lead to consume. There will be times, at least in the short term, when integrity is expensive, when it costs you something. It’s hard to bravely refuse what we know is wrong when it rewards us. And it’s hard to do what we know is right when it costs us. Author and columnist Peggy Noonan was correct when she said, “You can’t rent a strong moral sense.”20 Actually, you can’t even buy one. You have to develop it. You have to work at it, model it, teach it, and defend it. It takes integrity to withstand the seductions of our day.

Daniel Vasella, the CEO of Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis, addresses integrity directly and explicitly with his people: “I talk to my team about the seductions that come with taking on a leadership role. There are many different forms: sexual seduction, money, praise. You need to be aware of how you can be seduced in order to be able to resist and keep your integrity.”21

Rocks and Trees Are Neutral

Theologian John Calvin wrote in 1536, “The minds of all men have impressions of civil order and honesty.”22 And yet we are dual beings. We have impulses to do good and impulses to do evil—and we know the difference. The problem is we don’t always act on what we know. The great Russian novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn said that we have created “an atmosphere of moral mediocrity, paralyzing man’s noblest impulses.”23

Integrity is a matter of will.24 You have to want it more than you want whatever else is on offer. Journalist and politician Horace Greeley said, “Fame is a vapor; popularity an accident; riches take wings.”25 Do you believe that? This is not a philosophical question. You will have to answer that question today. You cannot stand on the sidelines and pretend to be above the fray.

Maybe your parents didn’t inculcate in you the importance of values. Maybe you’ve had role models who taught you to subcontract your moral reflections.26 Maybe you had a boss whose only permanent loyalty was to himself. Maybe the mass media taught you to gorge on power and profits. Maybe greed has dulled your senses. Maybe you had a philosophy professor who taught you there are no fixed principles.27 Maybe you know people who cheat and prosper.28Maybe you’re disoriented by the morally malignant air you breathe. Maybe you hold your nose as you look at a rogues’ gallery of retrograde characters and “the long freak show that was 20th-century world leadership.”29

Maybe. But you cannot be neutral. Rocks and trees are neutral—not people. You can’t wash your hands and be a philosopher. As writer, activist, and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel insisted, “We must take sides.”30

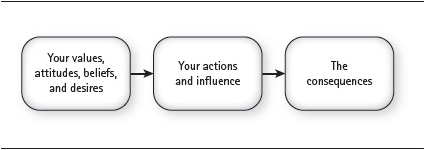

The Forces of Influence diagram shows what humans do every day (see figure 1.2). First, we are influenced by the actions of others. Second, we consider that influence and then consult our values, attitudes, beliefs, and desires. Third, we act and influence others. And finally, we enjoy or suffer the consequences of our actions. And please note that consequences can be suspended or delayed for long periods of time. Swift and perfect justice is not a characteristic of this life.

It is helpful to understand that we go through this process every day of our lives. It’s also critical to recognize that we have responsibility throughout the process.

You are responsible for your own values, attitudes, beliefs, and desires. You have the final and only say in how you choose to be influenced by others.

You are responsible for your own values, attitudes, beliefs, and desires. You have the final and only say in how you choose to be influenced by others.

You are responsible for the actions you take and the influence you have on others. You have moral agency—the volition to make your own decisions about what’s right and wrong.

You are responsible for the actions you take and the influence you have on others. You have moral agency—the volition to make your own decisions about what’s right and wrong.

Figure 1.2 The Forces of Influence

You are responsible for the consequences of your actions and their influence on others, including how your actions affect other people’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and choices.

You are responsible for the consequences of your actions and their influence on others, including how your actions affect other people’s thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and choices.

You are responsible and accountable for what you think, feel, believe, say, and do. And you are responsible for the consequences. As Frederick Douglass said at the funeral of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, “It was the glory of this man that he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result.”31

The Three Scorpions

I have worked with law enforcement agencies at the federal, state, and local levels. I have trained leaders from the Secret Service; Federal Bureau of Investigation; Federal Drug Enforcement Agency; Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; and a host of other agencies. If you look at the data for ethical misconduct across these organizations, as well as state and local agencies, the pattern is the same. There are three primary categories of ethical misconduct:

Lying, stealing, or cheating

Lying, stealing, or cheating

Substance abuse

Substance abuse

Sexual misconduct

Sexual misconduct

We call these categories of ethical misconduct the three scorpions. What is fascinating is that the pattern is consistent over time, and, not surprisingly, the same pattern of misconduct applies to the rest of us. If you look at time-series data documenting law enforcement officer wrongdoing over the past 50 years, it’s the same three scorpions. But that’s not all that is predictable about the three scorpions; we also know what officers do to put themselves in a position to be stung. The pattern leading up to a sting is just as predictable as the sting itself. And what is it? It’s simply the gradual deterioration of personal commitment to behave with integrity.

With few exceptions, officers begin their careers in a state of high commitment to their professional ethical standards. The most dangerous step for those who commit an ethical infraction is not the infraction itself but what we call the first justification. This refers to the first time the individual overrides an ethical standard by rationalizing it away.

A common initial infraction, for example, is violating a no-gratuity policy, which means accepting any gift, discount, or benefit one is offered by virtue of his or her profession. It’s almost always a small thing such as accepting a free cup of coffee. It sounds absurd to many people, but what we find is that little missteps create little vulnerabilities. You accept one gratuity, then another, then another. And then one day, you have unsupervised access to confiscated property, and you know that the property was acquired with drug money. You rationalize and take some. That is how it happens.

Thankfully, not everyone is equally susceptible to the slippery slope from the point of first justification. When it comes to integrity, maintaining it has everything to do with sweating the small stuff. If you are vigilant and circumspect with the little things, you never reach the point of first justification. What is predictable is preventable. If you never allow yourself to cut a corner, preserving your integrity is absolutely predictable and engaging in ethical misconduct is absolutely preventable.

Principles of Integrity

Early in my career, I spent five years as the plant manager at Geneva Steel, the last remaining fully integrated steel plant west of the Mississippi River. The plant itself was an old relic built by United States Steel during World War II, with machinery sprawled across 2,000 acres. We ran the plant 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, shutting down only for scheduled maintenance. Of course I couldn’t be there around-the-clock, so to cover more ground, connect with more people, and get my own sense of things, I made a habit of going on an occasional walkabout during swing and night shifts.

On one night’s walkabout, I started at what we called the “hot end,” making my way through the coke ovens and blast furnaces. The next stop was central maintenance. The people in central maintenance kept everything running; they were the electricians, pipefitters, millwrights, and other craft employees. It was about 2:00 a.m., and I wandered over to the break room near the electrical and machine shops. I opened the door. Pitch black.

I found the light switch and turned it on. Can you guess what I saw? That’s right: 30 employees sound asleep on makeshift cots—and getting paid. I had a long, hefty flashlight in my hand and one question in my head: Which end should I use? Apparently with little compunction, these men (and they were all men) were sleeping on the job.

Every man caught sleeping that night was issued a formal reprimand and suspended from his job for a week. What was fascinating was the way the men responded individually. Some tried to hide behind the union and duck personal responsibility. They went to great lengths to use the grievance procedure and formal arbitration not only to be cleared of wrongdoing but also to receive back pay for the time they were suspended. Other men took personal responsibility. They acknowledged their poor choice and wrote me letters of apology. Clearly, only the ones in the second category could look their children in the eyes and teach them about integrity.

Show Up and Follow Through

If integrity is basic honesty, a first principle is Be honest with your time and effort. I have a friend who has hired and managed thousands of people. I asked him this question: “What’s the first principle of integrity?”

“Come to work,” he said.

“That’s it?” I asked.

“That’s it. If you can be where you’re supposed to be when you’re supposed to be there, you have outperformed 25 percent of the human race.”

“Is there a second principle?” I asked.

“There is: follow through. If you can follow through, in other words, do the work that you’re assigned to do. And I’m not even saying that you do it well; but if you’re trying, even though you are making mistakes, you have now outperformed 50 percent of the human race.”

“So, you’re saying that if you simply show up and follow through, you’re in the top half of performance?”

“That’s exactly what I’m saying,” he replied. “It’s the principle that Vince Lombardi taught the Green Bay Packers years ago: ‘We’re going to be brilliant on the basics.’32 The ultimate basics are to show up and follow through. It’s not easy to find people willing to do that.”

If we are not passing this basic test of integrity by showing up and following through, chances are we’re engaging in some form of self-deception, which is a low-cost way of self-medicating when we’re not happy with our lives. But like all other illicit forms of pain avoidance, it does not make things better.

For many people the cost/benefit calculation is whether the costs of showing up and following through are higher than the short-term costs of not. We often choose self-deception because we have created a tolerable working accommodation with what we consider low-grade forms of dishonesty. It may bother us not to show up and follow through, but not enough to bring us to our feet. So, we convince ourselves that it won’t matter, at least not today. We push it off. But as novelist, poet, and travel writer Robert Louis Stevenson is often quoted as having said, “Everybody, soon or late, sits down to a banquet of consequences.”33

Human beings tend to change their behavior at the precipice. It takes a lot before the motivation to change is stronger than the motivation to stay the same. Inertia is a powerful force. And even when we do gain a sense of urgency to change, that urgency tends to be a catalyst and not a sustainer. Unfortunately, many people are crisis-activated.

If you think about it, not showing up and following through represents a pattern of avoiding effort. Integrity requires a consistent pattern of allocating effort. Infrequent bursts of effort are a clear indication of an integrity problem. In the final analysis, the act of showing up and following through is a gift of integrity we give ourselves and then give to others.

Help Others Have Integrity

In most organizations the ethical conduct of leaders follows a normal distribution curve. There are highly ethical employees at one end and highly unethical employees at the other. The rest of the population “occupy morally,” as novelist and poet Thomas Hardy describes in Far from the Madding Crowd, “that vast middle space of Laodicean [half-hearted] neutrality which lay between the Sacrament people of the parish and the drunken division of its inhabitants.”34 What an organization and its leaders decide to do with that middle space often determines the organization’s success.

An organization’s ability to show integrity comes from uncompromising and deeply socialized values. It is a culture of ethical behavior that allows an organization to consistently keep its promises to its stakeholders over the long term, and keeping promises is the essence of high performance. Warren Buffett said, “Culture, more than rule books, determines how an organization behaves.”35

When leaders get serious about competing on values, the organization gets serious about competing on values. It develops a fine-tuned moral sensitivity that becomes imbedded in the culture. Over time employees who do not agree or cannot abide the values leave. Meanwhile those who stay begin holding their leaders to a high standard of integrity. If they misstep, the employees will not wink.

Bob Moritz, the US chairman and a senior partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers, illustrates the point: “If I were to say something that appeared to conflict with PwC’s stated values, it could go viral, and my credibility would be shot.”36 That is an incredibly good thing—a culture that holds its leaders accountable. How does it happen? It happens when leaders model ethical values long enough that those patterns of behavior become the prevailing norms of the organization.

The challenge today is that organizations recruit, hire, and onboard a higher percentage of employees who arrive with no moral compass, who do not self-govern, which makes the organization only as good as its control environment and system of corporate governance. Eventually, there is a breakdown in the system and a scandal on the way.

Protect Principles and Values

Think about this question: What is Google built on? The answer should give us clues about how desperately organizations need integrity. Of course, there is no perfect organization in the world, no complex adaptive enterprise that has the capacity to neutralize all competitive threats all the time. But Google is one of the best.

Is Google built on its proprietary technology—that original kernel of code developed by founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin that became Google’s proprietary Internet search algorithm? Is it built on Google’s mission to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”? Is it built on Google’s values as laid out in its Code of Conduct, at the core of which is the mantra Don’t be evil?37 The answer is yes. All three contribute to Google’s success and competitive advantage. But there’s an important issue here that relates to the useful life of these elements. At some point Google’s current strategy will become fully amortized and have to change. And its mission? That could change, too, if Google decides to apply itself to other kinds of businesses. What about its values? Will it ever throw out Don’t be evil? That would be catastrophic.

In early US history, we find a curious parallel between building a house then and building a modern organization today. When homesteaders pushed out the western frontier, they would find a fertile spot of land, build their homes, and settle until the prospect of better land, better conditions, and a brighter future appeared. Before they hitched their wagons and got back on the trail, they would burn their houses to reclaim the nails. The hand-forged nails were rare and valuable, a precious asset they could not afford to leave behind.

Regardless of the brilliance of your strategy, the magnetism of your vision, the soundness of your execution, and the intimacy of your customer service, next to the inherent worth of human beings, a company’s principles and values are its most precious asset. In time everything else will be discarded. Inevitably, strategy will reach the end of its useful life. How you create and deliver value will change, as well as all the scaffolding that supports it. Your systems, structure, processes, practices, roles, responsibilities, and technology are configurable parts. It’s all perishable, with one exception: fixed principles and core values. They must stay.

Principles and values are the basis of making and keeping promises to employees and customers. They provide assurance, confidence, and trust out of predictive understanding.38 They are the last and enduring source of value. When they go, everything goes. When an organization abandons its principles and values, it removes its moral infrastructure and collapses under its own weight. Too many leaders and too many organizations are compelled to “learn geology the morning after the earthquake,” as poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson once noted.39 The epitaphs of many failed organizations read Died of self-inflicted wounds because everything was negotiable.

Nothing about an organization’s strategy or business model is sacrosanct. But there must be a cutting point between principles and values and everything else. They represent precious, freestanding assets that must be independent of strategy. They provide continuity and identity when everything else is expendable. They represent the core element of the culture and the unchanging soul of the organization.

Cases in which leaders have successfully remodeled an entire enterprise represent organizational change in its comprehensive and supreme category. We learn from these cases that retaining principles and values during the process of change is not only possible but necessary to provide an anchor. Ironically, perhaps, organizations with the strongest principles and values often have the highest adaptive capacity because people attach themselves to them and understand that everything else is on the table. If you want to keep your promises, burn the house when it’s time to reinvent the company. But save the nails.

INTEGRITY: SUMMARY POINTS

Society is immoral in its feigned attempts to be amoral.

We have an integrity problem because the triangle of socialization is broken and we have embraced moral relativism.

You will constantly be tempted to engage in ethical misconduct. Integrity depends on fixed principles and moral values.

Model, teach, and defend integrity. You cannot be neutral.

You are responsible for:

Your values, attitudes, beliefs, and desires

Your values, attitudes, beliefs, and desires

Your actions and influence

Your actions and influence

The consequences of your actions and influence

The consequences of your actions and influence

To avoid the slippery slope, avoid the first justification.

Be consistent in showing up and following through. Creating a culture of integrity allows the organization to keep its promises.

When it’s time to abandon your strategy, do not abandon your principles and core values.

Integrity is a source of personal and organizational competitive advantage in the twenty-first century.