Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

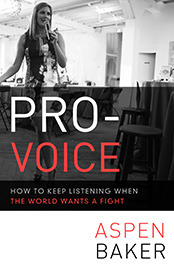

Pro-Voice

How To Keep Listening When the World Wants a Fight

Aspen Baker (Author)

Publication date: 04/30/2015

When Aspen Baker had an abortion at the age of twenty-four, she felt caught between the warring pro-life and pro-choice factions, with no safe space to share her feelings.

In this hopeful and moving book, Baker describes how she and Exhale, the organization she cofounded, developed their “pro-voice” philosophy and the creative approaches they employed to help women and men have respectful, compassionate exchanges about even this most controversial of topics. She shows how pro-voice can be adopted by anyone interested in replacing ideological gridlock with empathetic conversation. Peace, in this perspective, isn't a world without conflict but one where conflict can be engaged in—fiercely and directly—without dehumanizing ourselves or our opponents.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

When Aspen Baker had an abortion at the age of twenty-four, she felt caught between the warring pro-life and pro-choice factions, with no safe space to share her feelings.

In this hopeful and moving book, Baker describes how she and Exhale, the organization she cofounded, developed their “pro-voice” philosophy and the creative approaches they employed to help women and men have respectful, compassionate exchanges about even this most controversial of topics. She shows how pro-voice can be adopted by anyone interested in replacing ideological gridlock with empathetic conversation. Peace, in this perspective, isn't a world without conflict but one where conflict can be engaged in—fiercely and directly—without dehumanizing ourselves or our opponents.

Aspen Baker is the leading voice in the nation on how to transform the abortion conflict. She was a finalist for the 2014 American Express NGen Leadership Awards; was called a “fun, fearless female” by Cosmopolitan in 2013; was awarded the Gerbode Professional Development Fellowship in 2012; was named a “Women’s History Hero” in 2009 by San Francisco’s KQED during Women’s History Month; and was named “Young Executive Director of the Year” in 2005 by the Bay Area’s Young Nonprofit Professionals Network. Aspen served on the City of Oakland’s Public Ethics Commission 2011–2014. As a spokesperson for Exhale, she has been featured by media outlets across the country, among them CNN Headline News, Fox National News, Ladies’ Home Journal, Cosmopolitan, Glamour, the New York Times, National Public Radio, Newsweek, the New Republic, Alternet, and Bust. Her essay “My Abortion Brought Us Together” was included in the anthology Nothing but the Truth So Help Me God: 51 Women Reveal the Power of Positive Female Connection. She often writes for sites like the Stanford Social Innovation Review and Huffington Post. Aspen is a graduate of UC Berkeley, and she lives in Oakland, California, with her family.

—Publishers Weekly

“I recently learned that I already was pro-voice, and when you read this book you will likely discover that you are too. Together we can transform the ‘us versus them' dynamic that dominates our politics and media. Together we can create a new norm of respectful, caring engagement.”

—Joan Blades, founder of MoveOn.org, MomsRising, and Living Room Conversations

“With Pro-Voice, Aspen Baker revels in the deep discomfort of ambiguity rather than the shallow, sure waters of polemic. It is a testament to the transformational possibility of exploring the neglected gray area beyond the overly traveled black and white. I've never read anything quite like it.”

—Courtney E. Martin, author of Do It Anyway

“Aspen Baker takes one of the most contentious issues of our age and pulls an unexpected magic trick. Instead of delivering up a call to arms, she opens up a safe place for empathy, caring, and transformation.”

—Glynn Washington, creator and host of NPR's Snap Judgment

“In this wise and compassionate book, Aspen Baker makes clear how strange it is that the people who battle over abortion policy rarely hear the stories of women who have actually had abortions. With sensitivity and insight, she shows that people's personal stories can transform the debate. Pro-Voice is smart, provocative, and, finally, heartening.”

—Francesca Polletta, Professor of Sociology, University of California, Irvine, and author of It Was Like a Fever

“Aspen Baker's sharply insightful new book illuminates the refreshing—and groundbreaking—attitude she takes toward abortion, a stance that embraces the emotional complexity of women's abortion experiences and reveals the discussion's many gray areas that are so often obscured by political gamesmanship.”

—Martha Shane, filmmaker, After Tiller

“Thank you, Aspen, for asking the global community to create an environment of compassionate pro-voice dialogue around this ubiquitous, incendiary issue. May this book birth the healing we all need.”

—Deborah Santana, author, philanthropist, and founder of Do a Little

“The pro-voice movement Aspen Baker founded in Exhale is based on the idea that we are all storytellers, with the right to our own stories; specifically that every woman has the right to her own feelings about the experience of abortion, whatever they might be. As a journalist who writes about reproductive rights, I truly believe this approach is the only way to bridge a divide in this country that is putting woman's lives in peril.”

—Liz Welch, award-winning journalist and coauthor of The Kids Are All Right and I Will Always Write Back

“We have less and less authentic space for dialogue in our country, yet Aspen Baker has taken the power of listening into the most contentious of territories, the abortion debate. She has shown that the stories that emerge when someone feels respected and safe enough to share them have the power to heal. We can choose to listen, and if we do, perhaps we can create a healthier society.”

—Joe Lambert, founder and Executive Director, Center for Digital Storytelling

“The abortion debate—or rather, standoff—is one of the most polarizing in our polarized country. Pro-Voice creates humane connections across the passion-filled gulf that divides abortion conversations; then, as Jonathan Powell has also written recently, ‘There is no conflict in the world that cannot be solved.' If that is not a reason for hope, what is?”

—Michael Nagler, author of The Search for a Nonviolent Future and The Nonviolence Handbook and President, Metta Center for Nonviolence

“In Pro-Voice, Aspen Baker raises a bold mandate that we hear people's abortion stories and imagines a world in which abortion is understood not through conflict but through empathy, regardless of one's politics. Baker shows, despite the loud rhetoric, that personal experiences with abortion are rarely spoken, and even more rarely are they compassionately heard. Proudly defying political categorization, Pro-Voice challenges everyone to step away from the fight in favor of deeper understanding. This is a most courageous and necessary book.”

—Marjorie Jolles, PhD, Associate Professor, Women's and Gender Studies, Roosevelt University

“We've made great progress on tough social issues by sharing our stories authentically. Pro-Voice dives into that topic and makes it actionable. If you're an organizer it's a must-read in 2015!”

—Raven Brooks, Editor, Netroots Nation

“In Pro-Voice, Aspen Baker shows us how to make America's abortion wars a relic of the past. Sharing and listening can heal old wounds and generate a new understanding and respect for this deeply personal issue.”

—US Congresswoman Gwen Moore

“In a world where everyone forces you to chose a side around abortion, Pro-Voice challenges all of us to put empathy first and ideology second. Aspen Baker radically reframes our current culture war over abortion by putting stories first. By centering the voices of women, Baker clearly explains that actual conversation—not preaching or stonewalling—is the only way to move forward.”

—Latoya Peterson, feminist, activist, and owner and Editor, Racialicious.com

“The best social and policy change begins with having discussion in the real world with real people. In this book, Aspen shows us a way to listen to women in a deeper way, creating a space for us to see the complexity of experiences with abortion. This is the kind of space that will help us reach across the divisions that often separate us and see the humanity in each other. Bravo, Aspen and pro-voice!”

—Eveline Shen, MPH, Executive Director, Forward Together

Preface

Introduction

Chapter 1: The Birth of Pro-Voice

Chapter 2: America's Abortion Conflict

Chapter 3: Listen & Tell Stories

Chapter 4: Embrace Gray Areas

Chapter 5: Shape What's Next

Conclusion

Pro-Voice Resources

Notes

Acknowledgments

Index

About the Author

Chapter 1

The Birth of Pro-Voice

I grew up in the middle of our nation’s wars over abortion.

In 1976, the year I was born, the first clinic bombing was reported. The 1980s, my formative childhood years, were dominated by the impact of aggressive pro-life protests. California, my home state, had one of the most successful anti-abortion campaigning organizations around: more than 40,000 pro-life activists were arrested while protesting abortion clinics during a four-year period in the ’80s.1

As I was growing up in Southern California, it wasn’t unusual for me to see a huge picture of a bloody, dismembered fetus on a massive sign attached to the side of a minivan driving up and down the freeways near my home. I was certainly affected by pro-life public-awareness efforts but unaware of the violence against clinics. I grew up without a TV, so if these events were covered on the news, I never saw them.

As regular attendees of what I like to call a “surfing Christian” church and school, both nondenominational, my family and I spent time with other church and school families on the beaches of my hometown. San Clemente is steeped in surfing culture: it’s the home of Surfing Magazine; surf legends such as the Paskowitz, Fletcher, Beschen, and Gudauskas families; iconic surf brands such as Rainbow Sandals and Astrodeck; the nonprofit ocean conservation organization the Surfrider Foundation.2 To top it all off, our “Spanish Village by the Sea” was made famous by Richard Nixon during his presidency as the location of his “western White House.” Everyone, including many of the moms and all the kids, surfed, and in our circle, a special occasion meant it was time to pull out a nice Hawaiian shirt or sundress and wear the good flip-flops. Only the preacher wore a suit. Everyone was pro-life, and we all mourned the tragedy of abortion, but no one ever invited me to a protest, and as far as I knew, no one in our community participated in one, either—violent or not.

But we did put our pro-life Christian views into practice. Ever since I was young, my family and I traveled with church groups to Tijuana on missionary trips where I never saw anyone preach or try to convert others. We were there to chip in and help local orphanages survive. The dads worked on building clean bathrooms, and the moms spent all day in the kitchen making food. My younger sister and I spent the day hanging out with the babies. As a young girl, I found it hard to hear that the baby sitting on my lap—the one resigned to the flies in her eyes, nose, and mouth, despite my constant attempts to shoo them away—had been found by one of the adults at the local trash dump, where they went early each morning to look for abandoned babies. I loved babies. In fact, I spent less time with my own peers in Sunday school class than in the nursery, caring for the infants during church services.

Outside of these trips to Tijuana, it wasn’t unusual for my dad to bring home a stranger he had just met who needed a place to crash for the night, or for my family to spend Thanksgiving at a local soup kitchen. We lived pretty close to the bone ourselves. My parents basically made minimum wage in the 1980s, and I never earned an allowance. I started making my own money at 10 years old with—you guessed it—babysitting gigs, and the money I started to save then helped me pay for college later. But that wasn’t my only job. I also had a paper route at 10, the first girl to get the job from the local boys. Even though I read the paper every day before making my rounds, I don’t remember tracking the abortion fights.

Our community was white, working class, and not well educated—the dads I knew were plumbers, contractors, and teachers, and most of the moms worked as assistants and receptionists in local doctors’ offices or were teachers too. When I was young, my dad had every kind of odd job—beekeeper, chimney sweep—and my mom worked as a cocktail waitress. My dad would often take my little sister and me to have hot cocoa at the bar when my mom was working late into the night. Later on, both of my parents got better jobs working for the wealthy—my dad as a private pilot for company CEOs and my mom as a housecleaner. Homeschooled for a few years, I often did my work at the kitchen tables of families whose homes were several times the size of our own while my mom scrubbed their houses clean.

We all cared about God, the less fortunate, and the ocean. I don’t remember a single political conversation, but I do know that I was raised with a charitable bent in our pro-life views, not a violent, judgmental one. As a kid, I remember a couple of teenage girls who got pregnant and had babies at a young age, and I promised myself that it would never happen to me. It was hard to believe that I could ever be in that position, getting pregnant when I didn’t want to be. If the unlikely ever happened, I always assumed I’d have the baby.

I knew I could never kill my baby if I got pregnant. And then I did.

![]()

I had come a long way since my childhood on the beaches of San Clemente. I’d followed in the family footsteps set out by my grandfather, my uncle, and my dad, who had all worked as professional pilots, and started taking flying lessons while still in high school. I was learning how to land a single-engine Cessna airplane at small airports throughout San Diego while I got to know the Alaskan bush-pilot character of Maggie O’Connell on Northern Exposure along with the rest of America. After graduation, I quickly made my way to Alaska, where I learned how to land a plane on rivers, lakes, and glaciers, among having other adventures.

They say that women headed to Alaska alone are either running to or running from a man, and upon arrival they find that the “odds may be good” for finding a husband but the “goods are odd.” The Fairview Inn in Talkeetna, where I lived for a summer working for a local bush-flying outfit, had photo albums full of local men looking for a female mate. Their main requirements for a potential partner were that the woman be “quiet” and be able to “skin a moose.” Beyond its breathtaking beauty, the quirky honesty of Alaska was one of the things I loved the most.

There’s a lot of freedom in such a big place, and with it comes the harsh realities of inhabiting a rugged, wild land. Getting charged by a mama grizzly bear on a deserted trail once was enough for me. So too was knowing that not all of the courageous, passionate mountaineers I met would come back from their adventures alive. When I was 20 years old, I hauled the body bag of an older East German man off a small plane and had to organize how to get his remains and belongings home. Before he headed into the mountains, I’d spent hours with him and his climbing partner, who talked about how they dreamed of climbing Denali while confined by communism behind the Berlin Wall. The man’s dream ended tragically in an avalanche, and yet he inspired me to always pursue my own.

After Alaska and a brief stop living at home, attending community college in Orange County, I got accepted into UC Berkeley. I paid my way through school, selling everything from lattes and cocktails to bikes and skis at the local REI while earning my degree in peace and conflict studies. A voracious reader who had spent hours at the local library from a young age, I discovered and was politically transformed by The Autobiography of Malcolm X at age 15. By reading his story, I learned how to connect the dots between the hardships I saw in Tijuana or at the local soup kitchen and a broader social system of inequality and discrimination. I sought a college education that would teach me how to right the wrongs of injustice. I imagined that after graduation, I’d travel the globe on peaceful, humanitarian missions to serve those hurt in conflict zones and uplift those silenced by political repression.

Then everything changed—sort of. Three months after graduating college and three months into a new relationship, I found out that I was pregnant.

I thought I’d have the baby, until I told the guy. He wanted me to get an abortion. It forced me to take the option seriously in a way I never had before. It was hard to come up with a picture of what an abortion would mean in my life. I could see the dismembered fetus on the side of the minivans from my childhood, yet I had no corresponding image of a woman who’d had one. No one had ever told me she’d had an abortion. I could only remember one rumor years before about a girl from high school whom I hadn’t known well, but everyone else I knew had had their babies. I had no idea how to make the decision. What criteria should I use? How would I know what the right decision was? Would I regret an abortion later?

It was during this time that I took the risk to confide in my friend Polly while we were closing up the downtown Berkeley bar where we both worked. When she told me about her own abortion, Polly gave me an unusual gift: the knowledge that I was not alone in my experience. Whatever I decided, someone I knew had been through this, too.

It was the strangest feeling to walk around pregnant, not wanting to be, knowing that I had this big secret and that no one could tell just by looking at me. I found myself more curious about other people’s private lives. What secrets were people holding that I couldn’t see? What major life decisions were they facing? Whom could they talk to?

The old adage about walking a mile in someone else’s shoes came alive. I promised myself that I would never judge anyone again. I hadn’t lived their life. I didn’t know what they knew, fear what they feared, hope what they hoped. I knew that we all needed the same thing: not to be rescued or saved from the pain and difficulty of our circumstances and choices, but to feel cared for and supported as we fought our own battles.

In the end, having the abortion was not so much about staying on some kind of life track or “getting back to normal” as it was about my need to sever all ties I had with the guy. It was a step toward the unknown. The abortion forced me to let go of the future I had spent several days imagining after I found out that I was pregnant. I wasn’t going to be a mom this time. I said goodbye to all the ideas, strategies, plans, and hopes I’d come up with as I tried to make having a baby work out somehow in my life. There is no do-over with abortion. I could never take it back. I knew it would always hold a place in my life’s story, and with just a few days to make such a life-altering decision, I had no way to know if it was the best one for me.

I didn’t know who I would be after an abortion.

While I had been aware of the abortion debate before my abortion, I didn’t give it much attention. After my abortion, I listened more carefully, but all I heard was yelling and screaming. Noise. Anger. Outrage. It seemed to come from all sides. I couldn’t distinguish one side’s voice from the other. It was toxic and polarizing and full of judgment, finger-pointing, and blame. I felt grateful for my legal, covered-by-health-insurance abortion—absolutely—and yet once it was over, I was pretty mixed up about it.

I didn’t hear a voice like mine in the debate.

I searched for support, people and places to go talk to about my abortion. Even in Berkeley, California, all I found were Christian, pro-life organizations that wanted me to seek forgiveness from God. That wasn’t what I needed. The pro-choice side had nothing to offer. If the pro-life side considered abortion one of life’s biggest sins, then the pro-choice side seemed to consider it no big deal, an experience not worth talking about. I eventually found my way to a private therapist whom I paid in the cash I earned from my bartending tips. Ever since I’d known what an abortion was, I told myself I’d never have one, and then I did. I didn’t know if my abortion was aligned with my values or an aberration, inconsistent with who I was. My life wasn’t so black and white anymore. It had gotten very, very gray.

I now knew that I wasn’t alone, but I didn’t understand why people weren’t talking about their own abortions. I wondered how things would change if we did.

I no longer needed to travel the globe to support and uplift those hurt by conflict and repression. America’s abortion wars were in desperate need of their own humanitarian, peaceful mission, and I was determined to respond to the crisis.

Nonviolence Reimagined

In his final book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “I suggest that the philosophy and strategy of nonviolence become immediately a subject for study and for serious experimentation in every field of human conflict.”3

After my abortion, I took up Dr. King’s challenge. I wanted to put my peaceful values into action and experiment with nonviolence on the issue that had unexpectedly landed at my front door. I now had a personal stake in the abortion debate, but I didn’t want to fight to win. I wanted to transform the war into peace.

Since 2000, I have devoted my life to this experiment.

I cofounded Exhale to put nonviolent theories and ideas into real-life practice. Our programs and messages infuse love, compassion, and connection into the polarizing debate, diffusing tensions, increasing understanding, and promoting wellbeing. Listening and storytelling are the primary tools of our trade. The gray area is our landscape. We coined “pro-voice” in 2005 to inspire others to join our growing movement of peacemakers.

Months after my abortion, as I was researching abortion on the way to founding Exhale, I walked into a local Berkeley bookstore in search of a self-help book for women who’d had abortions. I was hoping to find something that could provide detailed information about all aspects of the procedure—from the medical and physical elements to the emotional ones—with voices of women sharing their stories and advice, including the ways they felt about the loss of their fetus. I found nothing like it on the shelves, so I went to the clerk to ask for help.

When I told her my request, she looked nervously at me, turned red, got flustered, and blurted out, “But abortion is a choice!” She may have repeated it a few times.

“True,” I said, “and I was hoping to find a book about women’s experiences.”

“All abortion books are under politics,” she said before walking away quickly.

I looked under politics, and sure enough, there were a few books about abortion there, but nothing was written for a woman who’d had one or was thinking about having one. Abortion was considered a political, private choice, but rarely was it addressed in personal terms. The clerk at the Berkeley bookstore wasn’t the only one to think of abortion so narrowly.

As much as I liked and appreciated the doctor who did my abortion, he gave me the same message. He made it a point to say that I’d never have to tell another person about it. He informed me that no doctor would be able to tell that I’d ever had one. From the very beginning, the message was that my abortion was private, a secret, not something to be shared with others, even my other doctors.

Later, a fertility specialist told me at a conference how much this sentiment had hurt his practice, because women later in life who were trying to get pregnant would hide their past abortions out of shame. But, he told me, a past pregnancy is one of the best indicators of someone’s future ability to get pregnant. A patient’s hiding of such critical information made it difficult for the doctor to understand his patient’s whole history, and it prevented him from offering real, medically proven hope to the woman and her partner.

We at Exhale weren’t alone in our desire to forge a new way forward on the abortion debate. The year we adopted “pro-voice,” Asian Communities for Reproductive Justice (now called Forward Together) published their vision for a broad-based reproductive justice movement led by women of color, and pro-choice leader Frances Kissling published her seminal piece “Is There Life After Roe?” on the importance of valuing the fetus alongside women’s rights.4 Anna Quindlen wrote in Newsweek that in all her years as an opinion columnist, the debate over abortion had hardly changed, noting, “Leaders of the opposing sides have been frozen into polar positions.” Quindlen acknowledged that abortion doesn’t fit “neatly into black-and-white boxes, it takes place in that messy gray zone of hard choices,” writing that “we insult ourselves by leaving its complexities unexamined.”5

During his 2009 commencement address at Notre Dame, President Obama put out a call for more civility, asking opposing sides to at least try to “discover the possibility of finding common ground” and help “transform the culture war into a tradition of cooperation and understanding.”6 But when the next abortion battle was waged a year later, this time over the Stupak-Pitts Amendment, which would limit abortion funding in the Affordable Care Act, the common-ground rhetoric was quickly abandoned in favor of the usual polarizing talking points.

There is a better way to do this, but the conflict is so effective at sweeping the nation into its vicious cycles that resistance to its power is short-lived.

There have been a handful of efforts designed to confront America’s abortion wars over the last 40 years. The most famous attempt is the one led by the nonpartisan Public Conversations Project, in response to the 1994 murder of two women who worked in a Brookline, Massachusetts, abortion-providing clinic. For five years, six pro-life and pro-choice leaders met in facilitated confidential conversations in an attempt to practice mutual respect across their differences. After Dr. George Tiller, one of just a few doctors who performed abortions later in pregnancy, was murdered in his church in Wichita, Kansas, in 2009, the pro-choice website RH Reality Check (rhrealitycheck.org) launched an online effort called “Common Ground” with the hope of bridging America’s divide on abortion. But the forum lacked the full support of RH Reality Check’s leadership, and so it lasted less than a year.

In all cases, the focus of these peace initiatives has been on the activists and the leaders actively engaged on both sides of the fight. Not a single common-ground effort has sought to include or directly address the lived experiences of people with abortion. Exhale is the first to attempt to put the voices and leadership of women—and men—who have gone through abortions at the center of organizing efforts for abortion conflict transformation.

Exhale’s pro-voice philosophy is a 15-year experiment in the application of nonviolence to America’s cultural conflict over abortion. We didn’t invent pro-voice to help one side or the other of the abortion wars to declare a final victory, nor was it created with any particular set of policy goals or objectives in mind, even those considered “common ground.” Pro-voice is an evolving theoretical framework with a set of concrete tools to help people and groups create meaningful connections across their differences—whether they are political, personal, or cultural—with the goal of making conflict more compassionate and respectful. It has applications and benefits far beyond the issue of abortion.

Pro-Voice = Listening + Storytelling

At one end of the room was a sign that said “Agree.” The other end had a sign that said “Disagree.” Standing at different points across the spectrum in between were women of different ages and ethnicities. One was visibly pregnant. They had just heard the statement “Abortion is a form of killing” and had moved to stand in the position that indicated their vote. “It’s not a baby yet,” said one young woman standing under Disagree, “so I don’t think it’s killing.” “Everything in your body is alive, so just like you kill cancer living in your body, an abortion kills something that is living,” said another, who was standing under Agree, adding, “I don’t know if it matters whether or not it’s a baby.”

Hearing this exchange, other women in the group changed their positions. They moved to different areas on the spectrum and then shared their reasons why. More statements, such as “It’s better to have an abortion early in pregnancy” and “Abortion is a form of birth control,” were read out loud by the trainer. Each time, the women moved to different points across the spectrum between Agree and Disagree, and each time, they spoke about where they had landed and why.

Often, people shifted their positions after listening to others speak.

The 12 women going through the exercise were all in training to be talkline counselors at Exhale. Each of them had applied and then been carefully screened and interviewed before being accepted into a 60-hour training, in which they learned how to answer calls from women and men in search of emotional support after an abortion. As a group, these women explored such questions as whether abortion was killing, because many of the people they would be talking to on the phone had considered it that way.

The goal of this training exercise was not to find agreement among the group or even to debate the statements. Instead, the exercise was used to surface how diverse values and beliefs can shape our understanding of personal abortion experiences, even among a like-minded group of people who share a common goal.

The trainer had done this exercise with volunteers many times, and when she closed it, she always asked the group, “Can you imagine doing this exercise with people we gather randomly off the street outside our office? Talking about abortion in this way is not safe in public or with strangers, which is why it’s so important that we create a safe space for women and men to feel heard, no matter what, on our talkline.”

Ten years later, in the middle of winter in New York City, three young women stood in front of a room of complete strangers, a classroom of college students, and shared their layered, complicated personal truths about abortion. Not a single one of their stories fit easily into a box marked pro-choice or pro-life. In fact, one of them told how it was these very boxes that had caused her so much distress after her abortion. She couldn’t make her feelings fit a political agenda. In any typical public setting, these women’s stories would raise the question “What’s the point?” Stories about abortion are usually told in simple, black-and-white terms with clear moral and political agendas.

However, these stories were ambiguous, and yet their impact was undeniable.

“This workshop isn’t what I expected,” one student said. “I came in wearing my armor. It turns out I didn’t need it.”

Exhale’s 2013 national Sharing Our Stories Tour—a program in which five women shared their personal abortion stories with people on college campuses, in churches, and in community centers across the country—shattered expectations and dismantled stale assumptions about what happens when abortion is discussed openly between people who have different views on the topic. In Austin, Milwaukee, Chicago, New York City, and the San Francisco Bay Area, the women shared their stories in pro-voice workshops they led, teaching audiences how to be empathetic through listening and storytelling.

Heavily evaluated by a consulting firm specializing in measuring social impact, audiences reported that they had been moved and transformed by what they had experienced.7 Here are some of the comments that the audiences shared:

“Due to the diversity of perspectives and feelings, I felt … more willing to share my experience and ask questions.”

“Due to the diversity of perspectives and feelings, I felt … more willing to share my experience and ask questions.”

“I was surprised by the speakers’ compassion, empathy, and sensitivity to those who oppose them.”

“I was surprised by the speakers’ compassion, empathy, and sensitivity to those who oppose them.”

“I am personally pro-life and often feel shut out or judged because of my opinion. However, I could one day be in the same position and respect everyone regardless of political stance.”

“I am personally pro-life and often feel shut out or judged because of my opinion. However, I could one day be in the same position and respect everyone regardless of political stance.”

“It made me feel at ease to learn that men have a role and a place in all of this that is respected and appreciated.”

“It made me feel at ease to learn that men have a role and a place in all of this that is respected and appreciated.”

“In the future, I will be more thoughtful about when it’s appropriate to engage politically and when it’s better just to hear a person as a human being.”

“In the future, I will be more thoughtful about when it’s appropriate to engage politically and when it’s better just to hear a person as a human being.”

Over 88 percent of audiences on the tour heard a new perspective about women’s experiences with abortion. And the diversity of the abortion stories helped create an environment where different feelings, thoughts, and opinions were welcome. Ninety-seven percent of audience members thought that the workshop was respectful of diverse experiences.

These pro-voice workshops broke every rule about what’s supposed to happen when strangers talk openly about abortion. You can do it, too. With pro-voice as your guide, controversial topics like abortion can bring people together, not drive them apart.

In Pro-Voice, I show how listening, storytelling, and embracing gray areas create unexpected possibilities. I offer stories, case studies, and ideas that I hope will inspire readers to make pro-voice their own. For the purposes of this book, I focus on the high-level principles and components that are fundamental to the pro-voice practice. I review how America got so stuck on abortion and the challenges that women who have abortions face when they speak personally and publicly about their lives. I explore what it takes to infuse creativity and openness into a decades-long stalemate; and I share the successes, failures, and lessons learned in the pro-voice experiment thus far.

Throughout this book, I use the phrases “women who have had abortions,” “people who experience abortion,” and “women and men” in an attempt to acknowledge the incredibly diverse array of people who are directly affected by an abortion. There are many challenges in speaking to and about all these groups, including the limitation of pronouns to represent the spectrum of gender identities and the natural emphasis on the lived experience of a person who physically undergoes the abortion procedure. Remember that even a secret abortion still takes place within the context of a woman’s relationships, however healthy or abusive they may be. Her partner, family, and friends have their own personal experiences of her abortion, as do those providing her medical care. Though I use the term fetus throughout the book, I am quite comfortable calling it a baby or an unborn child. No word is off-limits if it’s been used by a woman to describe her own experience with abortion, and no political alignment is implied in my own word choice.

These are the guiding beliefs of the pro-voice philosophy:

Pro-voice connections are radical acts of courage that can change the world. In the midst of hostility, attacks, and demonization, creating meaningful connections across differences generates new possibilities for change and transformation.

Embracing a diversity of voices, including those that are hidden, reveals new possibilities. Whether it’s the pro-choice woman who regrets her abortion, the pro-life woman relieved by hers, or the experiences of the men involved in abortion decisions, the voices and stories that disrupt conventional black-and-white thinking create opportunities for new ideas to emerge.

Separation damages human dignity. Not only must we advocate respect for our own humanity, but also we must affirm and sustain the dignity of our opponents.

Personal experiences should shape political reality. People’s real, lived experiences with polarized issues or stigmatized experiences can humanize toxic dynamics and illustrate complexity hidden within us-versus-them perceptions.

We continue the work of a long and powerful line of peacemakers. We have been influenced and inspired by those who have chosen love over hate and accept the task to do the same with the modern challenges of our evolving society.

All pro-voice strategies should be designed with the following goals:

Rehumanize toxic dynamics

Rehumanize toxic dynamics

Affirm and sustain human dignity

Affirm and sustain human dignity

Generate creativity and imagination

Generate creativity and imagination

Spur innovative thinking and action

Spur innovative thinking and action

Invite openness, engagement, and conversation where before there was black-and-white or us-versus-them thinking

Invite openness, engagement, and conversation where before there was black-and-white or us-versus-them thinking

Pro-voice tools have been piloted, tested, experimented with, fixed, adapted, improved, and perfected in a wide range of forums, online and in person, in big groups and small, with people of diverse values, beliefs, backgrounds, and experiences around the country. Each tool can be broken down into any number of specific steps to form a curriculum tailored for a range of individual, community, and organizational purposes.

These are the core tools of the pro-voice philosophy:

Listening. Central to Exhale’s work from the very beginning, active listening to truly understand where a person is coming from is the cornerstone of pro-voice practice.

Storytelling. It’s essential to let go of the desire to make the most persuasive narrative and instead support people as they tell their own stories, in their own words, and in their own time.

Embrace gray areas. The creativity and innovations needed for cultural change come from the ability to accept the ambiguities of human experiences.

Exhale’s community has been inspired and galvanized by what takes place in the intimate moments of connection between a talkline caller and an Exhale counselor, between women who are sharing abortion stories with each other, and between a storyteller and her audience. Given that there are often great differences between a storyteller and her audience, a counselor and a caller, or two women swapping stories with one another—they may be of different races, ethnicities, religions, ages, or education levels; they may speak with different accents and wear different styles; and they may have vastly different opinions about abortion—they can still connect in ways that empower, inspire, and make them hopeful for the future. These moments exist because even though the subject matter is highly polarizing, a pro-voice person will offer compassion and respond with empathy instead of defensiveness, even when under threat.

Practicing pro-voice behavior makes one incredibly vulnerable.

This type of nonviolent response—responding to hate with love or to attack with pacifism—has been called “moral jiu-jitsu.”8 By flipping the script, by changing expectations about how one is supposed to respond to hostility, conflict, or distress, we disrupt us-versus-them thinking. Opponents are unsettled. Gandhi called this nonviolent response to oppression satyagraha, and Dr. King called it “soul force.” One pro-choice activist referred to her work to publicly embrace the gray areas of abortion as a way to “take the wind out of the sails” of her pro-life enemies.

Pro-voice is the framework that applies these revolutionary concepts to the modern cultural warfare over abortion in America. Let’s see the opportunities in the obstacles of the abortion conflict and listen to the real human stories hidden behind the fight.