Download PDF Excerpt

Rights Information

Scenario Planning in Organizations

How to Create, Use, and Assess Scenarios

Thomas Chermack (Author)

Publication date: 02/14/2011

This is the most comprehensive guide available to the scenario planning process, offering a thorough discussion of the method's theoretical foundations and detailing a five-phase scenario planning system. Chermack uses a real-world case study to illuminate the entire process—from project preparation to scenario exploration, development, implementation, and project assessment. He provides specific techniques and tools for gathering and analyzing relevant data, structuring and managing projects, and avoiding common pitfalls.

-

Offers a comprehensive review of both the theory and practice of scenario planning

-

The only scenario planning book to address scenario implementation and assessment

-

Includes a casestudy to illustrate how the scenario planning system is applied in the real world

Scenario planning helps leaders, executives and decision-makers envision and develop strategies for multiple possible futures instead of just one. It enables organizations to become resilient and agile, carefully calibrating their responses and adapting quickly to new circumstances in a fast-changing environment.

This book is the most comprehensive treatment to date of the scenario planning process. Unlike existing books it offers a thorough discussion of the evolution and theoretical foundations of scenario planning, examining its connections to learning theory, decision-making theory, mental model theory and more. Chermack emphasizes that scenario planning is far more than a simple set of steps to follow, as so many other practice-focused books do -- he addresses the subtleties and complexities of planning. And, unique among scenario planning books, he deals not just with developing different scenarios but also with applying scenarios once they have been constructed, and assessing the impact of the scenario project.

Using a case study based on a real scenario project, Chermack lays out a comprehensive five phase scenario planning system -- project preparation, scenario exploration, scenario development, scenario implementation, and project assessment. Each chapter describes specific techniques for gathering and analyzing relevant data with a particular emphasis on the use of workshops to encourage dialogue. He offers a worksheet to help readers structure and manage scenario projects as well as avoid common pitfalls, and a discussion, based in recent neurological findings, of how scenario planning helps people to overcome barriers to creative thinking.

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

This is the most comprehensive guide available to the scenario planning process, offering a thorough discussion of the method's theoretical foundations and detailing a five-phase scenario planning system. Chermack uses a real-world case study to illuminate the entire process—from project preparation to scenario exploration, development, implementation, and project assessment. He provides specific techniques and tools for gathering and analyzing relevant data, structuring and managing projects, and avoiding common pitfalls.

-

Offers a comprehensive review of both the theory and practice of scenario planning

-

The only scenario planning book to address scenario implementation and assessment

-

Includes a casestudy to illustrate how the scenario planning system is applied in the real world

Scenario planning helps leaders, executives and decision-makers envision and develop strategies for multiple possible futures instead of just one. It enables organizations to become resilient and agile, carefully calibrating their responses and adapting quickly to new circumstances in a fast-changing environment.

This book is the most comprehensive treatment to date of the scenario planning process. Unlike existing books it offers a thorough discussion of the evolution and theoretical foundations of scenario planning, examining its connections to learning theory, decision-making theory, mental model theory and more. Chermack emphasizes that scenario planning is far more than a simple set of steps to follow, as so many other practice-focused books do -- he addresses the subtleties and complexities of planning. And, unique among scenario planning books, he deals not just with developing different scenarios but also with applying scenarios once they have been constructed, and assessing the impact of the scenario project.

Using a case study based on a real scenario project, Chermack lays out a comprehensive five phase scenario planning system -- project preparation, scenario exploration, scenario development, scenario implementation, and project assessment. Each chapter describes specific techniques for gathering and analyzing relevant data with a particular emphasis on the use of workshops to encourage dialogue. He offers a worksheet to help readers structure and manage scenario projects as well as avoid common pitfalls, and a discussion, based in recent neurological findings, of how scenario planning helps people to overcome barriers to creative thinking.

Thomas J. Chermack has studied and practiced scenario planning for over 15 years. His initial interest in scenario planning was due to its unique combination of analysis and creativity in exploring difficult status quo thinking an dhelp people see things differently.

Tom consults on scenario projects through his company Chermack Scenarios (www.thomaschermack.com) with organizations worldwide, including Saudi Aramco, Motorola, Directlink Technologies, Cargill, Emerson Process, General Mills, Centura Health, and others. Many of these projects have yielded profound insights for their organization leaders resulting in significant re-perceptions of their organizations, environments, and capabilities. In consulting with world-class organizations, Tom has seen the utility and effectiveness of scenario planing firsthand.

An assistant professor in organizational performance and change at Colorado State University, Tom teaches courses on scenario planning, human expertise, analysis in organizations, change management, and organization development. With a focus on the theoretical foundations and outcomes of scenario planning, Tom's research has won awards of excellence from the Academy of Human Resource Development and has appeared in scholarly journals as well as books and magazines. Much of his published work on the theory and practice of scenario planning includes numerous studies that document its benefits.

Tom is also the founder and director of the Scenario Planning Institute at Colorado State University (www.scenarioplanning.colostate.edu). The Scenario Planning Institute (the first of its kind in the United States) is a hub of activity related to scenario planning, including research, consulting with organizations worldwide, a program for certifying scenario planning facilitators, seminars, and other activities that link Colorado State University to organizations and members of the community, both locally and internationally.

Applied disciplines like scenario planning require both reflection and action--reflection, for understanding how scenario planning works and how it can be improved, and action, for putting new knowledge to use. Tom has made it a point of his career to study and apply scenario planning. An emphasis on both inquiry and application has provided a unique perspective, and a wealth of experiences that come together in this book.

Tom's experiences with the research and practice of scenario planning have yielded invitations to speak at organizations around the world, as well as present seminars, workshops, and keynote addresses.

Tom lives in Fort Collins, Colorado.

—Vance Opperman, President and CEO, Key Investment, Inc.; Audit Committee Chair, Thomson Reuters; and former President, West Publishing Company

“With extensive expertise, Tom Chermack spotlights scenario planning as a fundamental tool used by organizations to achieve long-term sustainability. This book helps me guide diverse management teams through strategic decision and problem-solving processes using a collaborative and forward-thinking approach.”

—Carla McCabe, Director of Human Resources, Technicolor

“Scenario planning has benefitted our entire organization by helping us understand a volatile environment and how to move forward. Scenarios have helped us think through options, create insights, and spark innovative ideas. Chermack's approach held us accountable and emphasized creative thinking as well as assessing where and how the scenarios added value.”

—James Steven Beck, MBA, CPA, Vice President—Administration, Eltron Research & Development, Inc.

“Professor Chermack has made the mysterious process of scenario planning available in a format accessible for both leaders of large corporations and small business owners. Creating a common working language about the future is essential for the long-term success of any enterprise. Tom's clear guidelines provide practical tools for organizations to create scenarios that will help them discover new ways of thinking, planning, and being.”

—Kim Cermak, President and COO, KDC Management, LLC

“Compelling and thoroughly researched, this book offers every business executive a playbook for including uncertainty in the organizational change process and driving competitive advantage.”

—Tim Reynolds, Vice President, Talent and Organizational Effectiveness, Whirlpool Corporation

“It has been forty years since we first started developing scenarios at Shell to help steer us into an unknown future. This is the fullest description I have seen of how the theory and use of scenarios have developed since.”

—Napier Collyns, cofounder, Global Business Network

“Chermack is well on his way to becoming a major resource for this important planning tool.”

—Vance Opperman, President and CEO, Key Investment, Inc., and Audit Committee Chair, Thomson Reuters

“With this book, scenario artists can learn to muster the analysis they need for credibility, and scenario academicians can get a sense of the artistry they will need.”

—Art Kleiner, Editor-in-Chief, strategy+business

Foreword by Louis van der Merwe

Preface

Part 1 -- Foundations of Scenario Planning

Chapter 1: Introduction to Performance-Based Scenario Planning

Chapter 2: The Theoretical Foundations of Performance-Based Scenario Planning

Chapter 3: The Performance-Based Scenario System

Chapter 4: Scenario Case Study

Part 2 -- Phases of the Performance-Based Scenario System

Chapter 5 Project Preparation Phase

Chapter 6 Scenario Exploration Phase

Chapter 7 Scenario Development Phase

Chapter 8 Scenario Implementation Phase

Chapter 9 Project Assessment Phase

Part 3 -- Leading Scenario Projects

Chapter 10 Managing Scenario Projects

Chapter 11 Human Perceptions in the Scenario System

Chapter 12 Initiating your First Scenario Project

References

Index

About the Author

1

Introduction To Performance-Based Scenario Planning

This book describes a method for including the realities of uncertainty in the planning process. Uncertainty and ambiguity are basic structural features of today’s business environment. They can best be managed by including them in planning activities as standard features that must be considered in any significant decision.

This book focuses on avoiding crises of perception. Scenario planning is a tool for surfacing assumptions so that changes can be made in how decision makers see the environment. It is also a tool for changing and improving the quality of people’s perceptions. Uncertainty is not a new problem, but the degree of uncertainty and the effects of unanticipated outcomes are unprecedented. Learning how to see a situation—complete with its uncertainties—is an important ability in today’s world.

This chapter presents some of the challenges posed by today’s fastchanging environment. A tool for dealing with those challenges has traditionally been strategic planning. Basic approaches to strategic planning are described; however, the rate and depth of change have increased over time to the point that those methods are no longer useful. Scenario planning emerged as an effective solution in the 1970s, and the ensuing history of scenario planning is discussed here. This chapter also describes a variety of major approaches to scenario planning, including their shortcomings. The fundamental problem with existing approaches to scenario planning is that they are not performance based. Evidence of this critical oversight is presented by reviewing the definitions and outcomes of scenario planning as they are described by major scenario planning authors. The outcomes they promote are generally vague and unclear. Finally, this chapter introduces performance-based scenario planning—which is the contribution of this book.

DILEMMAS

Some authors prefer to use the term dilemma instead of problem because the term problem can imply that there is a single solution (Cascio, 2009; Johansen, 2008). Most often, strategic decision making involves ambiguity and a realization that numerous solutions are possible. Each usually comes with its own caveats and difficult elements that must be considered. Hampden-Turner (1990) saw dilemmas as a dialectic and used the description “horns of the dilemma” to describe this way of observing specific dynamics in the environment. This way of describing complex dynamics takes a first step into looking for underlying systemic structure.

This book focuses on complex problems or dilemmas with unknown solutions. Therefore, its intent is to develop the understanding and expertise required to explore difficult, ambiguous problems and consider a variety of solutions in a wildly unpredictable and turbulent environment. Because there are no clear answers to questions of strategy and uncertainty, decision makers are compelled to do the best they can. These types of problems are the most complex, most ambiguous, and often the most deeply rooted. Experienced scenario planning practitioners have demonstrated their capacity to detect blind spots, avoid surprises, and increase the capacity to adjust when needed. Most important, modern-day dilemmas take place in an environment the likes of which we have never seen before.

THE ENVIRONMENT

Organizations operate in environmental contexts. These contexts include and are shaped by social, technological, economic, environmental, and political forces. The external environment has received much attention in literature from a variety of disciplines. Emery and Trist published a seminal work on the importance of the external environment in 1965. They suggested a four-step typology of the “causal texture” of the external environment:

Step 1—a placid, randomized environment

Step 2—a placid, clustered environment

Step 3—a disturbed, reactive environment

Step 4—a turbulent field

Few would disagree that most contemporary organizations are heavily steeped in turbulent fields. Turbulent fields are worlds in which dynamic processes create significant variance. These turbulent fields embody a serious rise in uncertainty, and the consequences of actions therein become increasingly unpredictable (Emery & Trist, 1965). These four different types of environments have existed over time, but today we are dealing with turbulent fields beyond the original conceptualization.

Reminding readers of Emery and Trist’s classification, Ramirez, Selsky, and van der Heijden (2008) use the ideas of turbulence and complexity to frame their edited book Business Planning for Turbulent Times. They make their case that turbulence and environmental complexity are undeniable features of the business environment by citing research showing significant increases in published material focused on turbulence and uncertainty. It could be argued that these descriptors are more relevant today than they were in 1965.

Another description of the external environment uses the terms volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity for the acronym VUCA (Johansen, 2007). VUCA originated at the U.S. Army War College, which has since become known as VUCA University. Indeed, the elements of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity are undeniably present in the operating environment of any organization—the only question is the degree to which each element may be in play.

These external environment elements have equal and opposite forces that must be understood and emphasized. For example, to overcome volatility, one must use vision; to address uncertainty, one must develop understanding; complexity yields to clarity; and ambiguity can be addressed with agility. Each of these solutions is based on an open-ended, continuous learning orientation (Johansen, 2007).

The general societal environment and organizations within it continue to evolve to new heights of complexity, turbulence, volatility, uncertainty, and ambiguity. The rate of change is not likely to slow, and most decision makers are simply trying to keep up. Timelines for strategic thinking are short. Organizations operating on a minimum of resources will find that eventually something must be given up. For many, the time to think strategically is sacrificed. Logically, this reaction is just the opposite of what is required if decision makers are to have any chance at navigating a chaotic environment that is challenging them.

A BRIEF EVOLUTION OF STRATEGIC PLANNING

Military planning has long concentrated on strategy principles dating back to early Chinese philosophers such as Sun Tzu and Japanese philosophers such as Miyamoto Musashi, as well as ancient scholars like Niccolò Machiavelli. These early opinions about battle positioning have heavily influenced modern thinking about strategy (Cleary, 1988; Greene, 1998). Through several world and national wars, the notion of planning for strategic warfare positioning has evolved dramatically (Frentzell, Bryson, & Crosby, 2000). While the history of military planning is extensive and has evolved in many ways completely on its own, military strategy has borrowed and contributed concepts from and to corporate planning over the years (Frentzel et al., 2000).

Alfred Sloan advanced corporate planning practices at General Motors in the 1930s. The concept of planning as a central organizational activity was further advanced by Igor Ansoff and Alfred Chandler. These strategy thinkers spent their time in the 1950s and 1960s trying to convince managers that their companies needed strategies. During this period, frequent links and parallels were drawn with military strategy and the events of the era. Economic forecasting was the key tool in the strategist’s arsenal of weapons for blasting a path to the desired future. This approach to planning continued through the 1960s and generally involved three phases—namely, defining the desired future, creating the plan (or steps to achieve the desired future), and then implementing the plan (Micklethwait & Woolridge, 1996). These phases also denoted the initial division between strategy formation and implementation, with the formation being a process reserved for senior executives and the CEO, and implementation being the job of managers. Strategic planning became increasingly complex over the next decade with the introduction of several levels of planning. A notable contribution of this time period was the Boston Consulting Group’s Growth Share Matrix. The matrix was intended to indicate a general strategy to executives and managers based on templates of opportunities and strategies in any industry.

In response to the demands of World War II, planning became a top priority for most industries. The military also heightened its connection to the research coming out of the RAND Corporation that was headed by Herman Kahn (Kahn & Weiner, 1967; Ringland, 1998). The developments in Kahn’s “future-now thinking” quickly translated into military efforts to predict the future (Kahn & Weiner, 1967), and military planning groups added physicists and mathematicians specializing in modeling (Ringland, 1998). Although much of the planning strategies used by the military were classified, it seems clear that the thinking going on in Stanford Research Institute’s Futures Group, and that of Herman Kahn himself at the Hudson Institute, provoked what became more widely known as simulations, or events that positioned participants in hypothetical situations.

Later, Forrester’s (1961) work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology also contributed greatly to the development of simulations, and his expertise was sought for military operations on several occasions. One of the applications of Forrester’s systems dynamics modeling was to uncover counterintuitive possibilities in the future. The essence of the Forrester systems dynamics models is to develop the underlying causal relationships that drive a specific dynamic. Through a process of identifying and modeling the size of stocks and the strength of flows, complex dynamics could be captured. These models also enabled an evidence-based argument about how specific dynamics might unfold in the future.

Military groups began using simulations to allow individuals to experience situations without the implications of their actions in those situations translating into reality (Frentzel et al., 2000). The emphasis on war games, the advent of computer modeling, and other technology produced by the military and industry in the 1950s and 1960s have led to elaborate training strategies involving virtual reality and devices such as flight simulators. Military planning has incorporated some of the early scenario planning concepts, but the core point of differentiation has been a lasting focus on prediction in military planning (Frentzel et al., 2000).

Michael Porter’s work on business strategy took a cue from some of the military planning concepts and applied them to business organizations. His work concentrated on the idea that there can be both unique solutions to strategic problems and general solutions that may be examined for relevance to any strategic situation (Porter, 1985). Porter’s work then shifted to the idea of competitive advantage and that, indeed, generic paths for achieving competitive advantage are freely available to any corporation and its planning analysts (Porter, 1985). Porter also stressed the idea that organizations should think of themselves as value chains of separate activities. Planning took a serious turn to focus on analysis until Japanese companies were performing as anomalies in Porter’s planning framework. Lengthy, formal, and involved approaches to planning came under tough scrutiny by overseas business leaders; eventually, even the Harvard Business School explored more simplified approaches to strategy.

The shift in thinking toward simplicity had an effect on most organizations. Many corporations ridded themselves of their planning departments as the concept of reengineering took center stage in the 1990s. Strategy consulting firms like McKinsey and the Boston Consulting Group shifted their expertise to reengineering to capture the rising demand. Planning practices in the 1990s and early 2000s became hybrids of everything from formalized annual retreats that attempted to re-create the days of planning, to simple strategies that could be communicated and rolled out to employees on business cards.

In light of the negative and devastating effects of many reengineering efforts, some companies have attempted to revive practices of strategic thinking in their organizations, and some companies have managed to hold onto their formal planning processes. The 1990s also brought about a concentration on developing strategic vision. Jim Collins, in his bestselling book Good to Great (2001), demonstrated how vision-led organizations are sustainably more profitable than others. He combined this point with a leadership theory called Level Five leadership that he described as a combination of fierce resolve and humility. This approach was thought to be the solution—somewhere between the bureaucratic formalized planning that was deemed a failure in the past and a strategy written on a cocktail napkin.

PHILOSOPHICAL VIEWS ON STRATEGY

There are three overarching paradigms of strategy (van der Heijden, 1997, 2005b). These philosophies are critical to understanding the context in which planning takes place. Although it is tempting to “choose” one of these philosophies with which one finds alignment, it is important to realize that all three of these views are valid. To place scenario planning in context, we must consider the backgrounds of each of these views: rationalist, evolutionary, and processual.

THE RATIONALIST SCHOOL

The rationalist school features a tacit and underlying assumption that there is indeed one best solution. The job of the strategist becomes one of producing that one best solution or the closest possible thing to it. Classic rationalists include Igor Ansoff, Alfred Chandler, Frederick Taylor, and Alfred Sloan (Micklethwait & Woolridge, 1996). The rationalist approach to strategy dictates that an elite few of the organization’s top managers convene, approximately once each year, and formulate a strategic plan. Mintzberg (1990) lists other assumptions underlying the rationalist school:

• Predictability; no interference from outside

• Clear intentions

• Implementation follows formulation

• Full understanding throughout the organization

• The belief that reasonable people will do reasonable things

The majority of practitioners and available literature on strategy is of the rationalist perspective (van der Heijden, 1997, 2005b). Although it is becoming clear that this view is limited, and as the belief in one correct solution wanes, the rationalist perspective is still alive and well, and fully embedded in many organizational planning cycles.

THE EVOLUTIONARY SCHOOL

With an emphasis on the complex nature of organizational behavior, the evolutionary school suggests that a winning strategy can only be articulated in retrospect (Mintzberg, 1990). Followers of this theory believe that systems can develop a memory of successful previous strategies. In this case, strategy is thought to be a “process of random experimentation and filtering out of the unsuccessful” (van der Heijden, 1997, p. 24). Organizations with strong cultures and identities often have trouble seriously thinking about alternative futures because the company brand is so influential.

The issue with this perspective is that it is of little value when considering alternative futures. This view can sometimes reduce organization members to characters of chance, influenced by random circumstances.

THE PROCESSUAL SCHOOL

The processual school asserts that although it is not possible to deliver optimal strategies through rational thinking alone, organization members can instill and create processes within organizations that make it a more adaptive, whole system, capable of learning from its mistakes (van der Heijden, 1997, 2000). Incorporating change management concepts to influence processes, the processual school supports that successful evolutionary behavior can be analyzed and used to create alternative futures. Van der Heijden (1997, 2000) offers the following examples of metaphors for explaining the three strategic schools:

• The rationalistic paradigm suggests a machine metaphor for the organization.

• The evolutionary school suggests an ecology.

• The processual school suggests a living organism.

Because van der Heijden views scenarios as a tool for organizational learning, he advocates the integration of these three strategic perspectives. “Organizational learning represents a way in which we can integrate these three perspectives, all three playing a key role in describing reality, and therefore demanding consideration” (van der Heijden, 1997, p. 49). It is widely accepted that effective scenario building incorporates all three of these perspectives (Georgantzas & Acar, 1995; Ringland, 1998; Schwartz, 1991).

HISTORY OF SCENARIO PLANNING

Scenario planning is a participative approach to strategy that features diverse thinking and conversation. Diverse thinking and conversation are used to shift how the external environment is perceived (Selin, 2007; Wack, 1984, 1985a, 1985b). The intended outcomes of scenario planning include individual and team learning, integrated decision making, understanding of how the organization can achieve its goals amid chaos, and increased dialogue among organization members (Chermack 2004, 2005). These outcomes collectively prepare individuals and organizations for a variety of alternative futures. When used effectively, scenario planning functions as an organizational “radar,” scanning the environment for signals of potential discontinuities.

Scenario planning first emerged for application to businesses in a company set up for researching new forms of weapons technology in the RAND Corporation. Kahn (1967) of RAND pioneered a technique he titled “future-now thinking.” The intent of this approach was to combine detailed analyses with imagination and produce reports as though people might write them in the future. Kahn adopted the name “scenario” when Hollywood determined the original term outdated and switched to the label “screenplay.” In the mid-1960s, Kahn founded the Hudson Institute, which specialized in writing stories about the future to help people consider the “unthinkable.” He gained the most notoriety around the idea that the best way to prevent nuclear war was to examine the possible consequences of nuclear war and widely publish the results (Kahn & Weiner, 1967).

Around the same time, the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) began offering long-range planning for businesses that considered political, economic, and research forces as primary drivers of business development. The work of organizations such as the SRI began shifting toward planning for massive societal changes (Ringland, 1998). When military spending increased to support the Vietnam War, an interest began to grow in finding ways to look into the future and plan for changes in society. These changing views were largely a result of the societal shifts of the time.

The Hudson Institute also began to seek corporate sponsors, which exposed companies such as Shell, Corning, IBM, and General Motors to this line of thinking. Kahn and Weiner (1967) then published The Year 2000, “which clearly demonstrates how one man’s thinking was driving a trend in corporate planning” (Ringland, 1998, p. 13). Ted Newland of Shell, one of the early corporate sponsors of scenario planning, encouraged Shell to start thinking about the future.

The SRI “futures group” was using a variety of methods in 1968–1969 to create scenarios for the U.S. education system reaching to the year 2000. Five scenarios were created; one entitled “Status Quo Extended” was selected as the official future (official future is a generic term to denote a desired future that has been “selected” by senior management). This scenario suggested that issues such as population growth, ecological destruction, and dissent would resolve themselves. The other scenarios were given little attention once the official future was selected. The official future reached the sponsors, staff at the U.S. Office of Education, at a time when President Richard Nixon’s administration was in full swing in 1969. The selected scenario was quickly deemed impossible because it was in no way compatible with the values that Nixon was advocating then (Ringland, 1998). The official future provided little insight into major issues of the time, and it failed to do more than present a report of present trends playing out into the future as they were expected to. The SRI went on to do work for the Environmental Protection Agency, with Willis Harman, Peter Schwartz, Thomas Mandel, and Richard Carlson constructing the scenarios.

Earlier, Jay Forrester (1981) of MIT was using similar concepts to describe supply-and-demand chains. The use of scenario concepts in his project was specifically aimed at stirring up public debate rather than solving a dilemma or issue. In other words, he used scenarios as tools for entertaining multiple sides of an issue and exploring the various viewpoints. The results were published by Meadows, Meadows, and Randers in 1992.

Scenario planning at Shell was well on its way. Ted Newland suggested in 1967 that thinking six years ahead was not allowing enough lead time to effectively consider future forces in their industry (Wack, 1985a). Shell began planning for 2000. Newland was joined by Pierre Wack, Napier Collyns, and others. When the Yom Kippur War broke out in 1973 and oil prices rose sixfold, Shell was prepared. The ability to act quickly has been credited as the primary reason behind the company’s lead in the oil industry over the years.

Shell’s success with the scenario planning process encouraged numerous other organizations to begin thinking about the future in this different way. Because the oil shock was so devastating to views of a stable future, by the late 1970s the majority of the Fortune 100 corporations had adopted scenario planning in one form or another (Linneman & Klein, 1979, 1983; Ringland, 1998).

The success of scenario use was short-lived. Caused by the major recession and corporate staffing reductions of the 1980s, scenario use was on the decline. It is also speculated that planners oversimplified the use of scenarios, confusing the nature of storytelling with forecasting (Godet & Roubelat, 1996; Ringland, 1998; Sharpe, 2007; Wright, van der Heijden, Burt, Bradfield, & Cairns, 2008). According to Kleiner (1996, 2008), the time had come for managers to realize that they did not have the answers to the future. Porter (1985) led a “back to the basics” approach suggesting that corporations use external forces as a platform for planning. In this time of evaluating how planning happens, many consulting firms began developing scenario planning methodologies. Huss and Honton (1987) described three approaches of the time: (1) intuitive logics, introduced by Pierre Wack; (2) trend-impact analysis, the favorite of the Futures Group; and (3) crossimpact analysis, implemented by Battelle. Royal Dutch/Shell continued to have success with scenario planning through two more oil incidents in the 1980s, and slowly, corporations cautiously began to reintegrate the application of scenarios in planning situations. Scenario planning has been adopted at a national level in some cases, and its methods have been successful in bringing diverse groups of people together (Kahane, 1992; van der Merwe, 1994). For example, scenarios were used to explore the potential transformation of South Africa at the end of apartheid (Kahane, 1992). Scenarios have also been used as tools for community building and dialogue (van der Merwe, 1994).

PUBLICATION ACTIVITY IN FUTURES AND SCENARIO PLANNING

As the world has become more uncertain, the need and therefore the popularity of scenario planning have increased. Scenario planning has seen considerable growth as a topic of publication in academic journals since the mid-1990s (Ramirez et al., 2008). In addition, scenario planning as a specific strategic management tool has also seen a rise in use, according to Bain & Company’s annual Management Tools Survey (Ramirez et al., 2008).

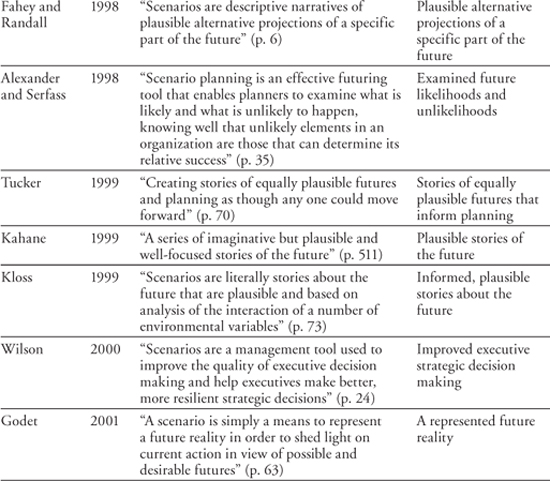

DEFINITIONS OF SCENARIO PLANNING

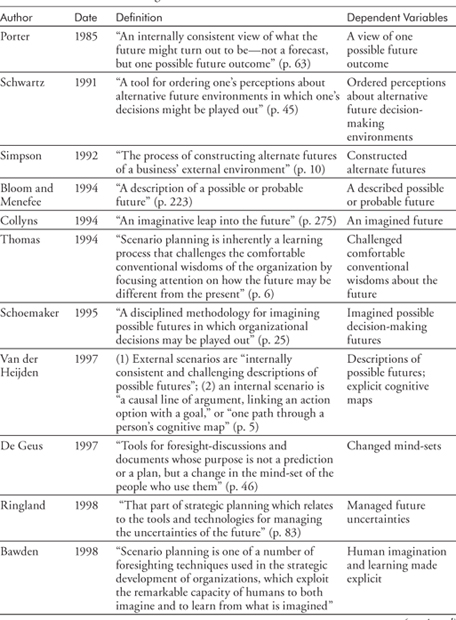

Scenario planning is still a relatively young discipline, and many variations have been developed. The diversity of thought concerning scenario planning is an asset in that it has brought about a variety of interpretations about what scenario planning is. However, the use of a variety of methods mandates close and careful study to determine what is effective and what is not. Variety can also be found in the available definitions and stated outcomes of scenario planning. Figure 1.1 provides a list of definitions in the scenario planning literature.

OUTCOMES OF SCENARIO PLANNING

Many of the definitions examined here do not explicitly state the outcome variables of scenario planning, which indicates that some authors may be unclear about the aims of their definitions. This also suggests that scenario planning professionals are just beginning to consider the importance of defining what they do and explicitly stating what they intend to achieve by doing it.

FIGURE 1.1 Scenario Planning Definitions and Outcome Variables

Figure 1.1 shows that almost half of the available definitions date from 1997 to the present. Such a surge of publication activity related to scenario planning suggests a recent increased use of this strategic tool. Of interest is that the first available definition of scenario planning is offered in 1985, yet the process has been applied in practice since the 1960s. The increase in recent scholarly literature around scenario planning suggests that the process is developing and maturing with the help of professionals concerned that scenario planning does not suffer the same inadequacies and criticisms that have been leveled against general strategic planning processes (Fahey & Randall, 1998; Mintzberg, 1994).

The dependent variables of Figure 1.1 can be synthesized into four major outcome categories of scenario planning:

• changed thinking,

• informed narratives or stories about possible or plausible futures,

• improved decision making about the future, and

• enhanced human and organization learning and imagination.

Of significant note is that none of the available definitions of scenario planning includes an outcome of performance improvement. Due to the depth of expertise and high costs usually associated with the practice of scenario planning, it is surprising that performance improvement has not been an explicit outcome of this strategic process. Some may simply assume that scenario planning will result in performance improvement. However, although such an assumption may be logical or known based on practical experience, there is little evidence that the practice of scenario planning actually results in performance improvement. Building this evidence can only help bolster the practice of scenario planning as a strategic activity. The lack of focus on performance improvement may be attributed to general difficulties in measuring the effects of scenario planning projects. Performance must be included and developed as a critical outcome expectation of scenario planning and as part of the definition of scenario planning. One approach to linking scenario planning to performance is described in detail in Chapter 9.

In an attempt to construct an integrative definition of scenario planning, it is important to include the outcomes stated in the available definitions highlighted in the next chapter in Figure 2.4. The following definition of performance-based scenario planning synthesizes the outcomes in Figure 2.4 and adds the performance orientation:

Performance-based scenario planning is a discipline of building a set of internally consistent and imagined futures in which decisions about the future can be played out, for the purpose of changing thinking, improving decision making, fostering human and organization learning and improving performance.

The performance orientation changes the game for scenario planning. An expectation of performance improvement forces a conversation about outcomes, without diminishing the capacity to wonder about the future. Having a performance improvement perspective means that there will be a way of determining whether the scenario project produced any benefits for the organization. So far, this question has been infrequently asked, and answers are often vague and unrelated to the initial reason for engaging in scenario work. It is important to clarify that a performance orientation does not preclude additional unexpected outcomes from emerging. They often do, and they can be very powerful. The performance orientation defines targets, identifies areas of potential leverage, and works to shift the thinking inside the organization. Logically, a performance orientation mandates assessment of the project. As noted, Chapter 9 lays out a comprehensive approach to assessing scenario projects.

LEARNING

Scenario planning most certainly involves learning. Arie de Geus (1988, 1997) wrote the foundational treatise “Planning as Learning” and later a book titled The Living Company in which he compiled decades of research showing that the companies in history with the greatest longevity were those that framed planning as a learning process and used tools like scenario planning to keep learning about how to maintain fit in their environments. Most likely, de Geus’s views were influenced by Pierre Wack and Ted Newland at Royal Dutch/Shell as Wack was famous for stressing, “Our real target was the microcosms of our decision-makers: unless we influenced the mental image, the picture of reality of critical decision-makers, our scenarios would be like water on stone” (Wack, 1984, p. 58).

Don Michael’s (1995) view of strategic learning (detailed in his book Learning to Plan and Planning to Learn) is quite suitable to the purpose of scenario planning:

It is imperative to free the idea of learning from its conventional semantic baggage. Learning used to mean (and for the most part still means) learning the answer—a static shift from one condition of knowledge and/or know-how to another. This definition of learning leads to organizational and stakeholder rigidification. But in the current and anticipated conditions of dramatic unpredictability, learning must be a continuous process involving:

1. Learning to re-perceive or re-interpret a situation,

2. Learning how to apply that re-perception to the formulation of policy and the specification of action (including evaluation of policy and action),

3. Learning how to implement those policies and intended actions, and

4. Learning how to keep these three earlier requirements alive and open to continual revision. (p. 46)

APPROACHES TO SCENARIO PLANNING

There are varying approaches to scenario planning. Each has developed out of various schools of thought, and it is important to review the alternatives here before proceeding. The major approaches to scenario planning reviewed here include these:

• Royal Dutch/Shell and Global Business Network

• The French School

• The Futures Group

• Wilson and Ralston

• Lindgren and Bandhold

• Reference scenarios

• Decision Strategies International

• Procedural scenarios

• Industry scenarios

• Soft creative methods

These approaches to scenario planning have all developed in practice. No doubt, the different techniques have evolved under slightly different circumstances, and each contributes to the body of scenario planning knowledge.

ROYAL DUTCH/SHELL AND GLOBAL BUSINESS NETWORK

The overarching view utilized by the Global Business Network (GBN) was born out of Shell’s application of scenario technology. GBN was founded by Peter Schwartz, Jay Ogilvy, Stewart Brand, Lawrence Wilkinson, and Napier Collyns. Pierre Wack first began applying Herman Kahn’s concepts in the 1960s and refined them into a proprietary framework stressing the big picture first, then zooming in on the details. Wack believed that to begin with the details was to miss some key dimensions of the building process. Schwartz took over as the head of Shell’s scenario division and eventually established a company, GBN, with a handful of other colleagues offering a variety of strategic business services worldwide. Schwartz (1991) gives a conceptual overview of the scenario building process in The Art of the Long View. At the center of GBN was a network of “remarkable people” (or RPs, as they became known) first used by Wack to challenge and shift the thinking and assumptions of decision makers within Royal Dutch/Shell.

Step 1 is to identify a focal issue or decision. Scenarios are built around a central issue outward toward the external environment. Scenarios based first on external environmental issues such as high versus low growth may fail to capture company-specific information that makes a difference in how the organization will deal with such issues (Schwartz, 1991). Accepted best practice is to engage the decision makers first in a conversation to uncover their current assumptions and concerns about the external environment and how they might unfold.

The second step is to identify and study the key forces in the local environment, which is logical after selecting a key focusing issue or question. Step 2 examines the factors that influence the success or failure of the decision or issue identified in the first step. Scenarios must be developed to shed light on the issue or question. Analyses of the internal environment and strengths and weaknesses are commonly conducted in this step as a way of identifying the internal dynamics that help or hinder strategy development.

Once the key factors have been identified, the third step involves brainstorming the driving forces in the macroenvironment. These include political, economic, technological, environmental, and social forces. Driving forces may also be considered the forces behind the key factors in Step 2 (Schwartz, 1991).

Step 4 consists of ranking the key factors (from Step 2) and the driving forces (from Step 3) on the basis of two criteria: (1) the degree of importance for success and (2) the degree of uncertainty surrounding the forces themselves. “Scenarios cannot differ over predetermined elements because predetermined elements are bound to be the same in all scenarios” (Schwartz, 1991, p. 167).

The results of the ranking exercise are to separate the important few from the unimportant many forces that are at play in the environment. One method of developing distinctive story lines is to identify two axes along which the eventual scenarios will differ. Another method is to simply develop stories that can be contained within the key driving forces at work. Again, these stories are intended to shed light on the focusing issue or question. Step 5, then, is the development and selection of the general scenario logics according to the matrix resulting from the ranking exercise. The logic of a given scenario will be characterized by its location in the matrix. “It is more like playing with a set of issues until you have reshaped and regrouped them in such a way that a logic emerges and a story can be told” (Schwartz, 1991, p. 172).

Step 6, fleshing out the scenarios, returns to Steps 2 and 3. Each key factor and driving force is given attention and manipulated within the matrix developed in the scenario logics of step 4. Plausibility should be constantly checked from this point, for example, “if two scenarios differ over protectionist or non-protectionist policies, it makes intuitive sense to put a high inflation rate with the protectionist scenario and a low inflation rate with the non-protectionist scenario” (Schwartz, 1991, p. 178).

Step 7 examines the implications of the developed scenarios. The initial issue or decision is “wind tunneled” through the scenarios. It is important to examine the robustness of each scenario through questions such as these: What will we do if this is the reality? Does the decision look good across only one or two scenarios? What vulnerabilities have been revealed? Does a specific scenario require a high-risk strategy?

The final step is to select “leading indicators” that will signify that actual events may be unfolding according to a developed scenario. Once the scenarios have been developed, it’s worth spending some time selecting identifiers that will assist planners in monitoring the course of unfolding events and how they might impact the organization.

THE FRENCH SCHOOL

When he took over the Department of Future Studies with SEMA group in 1974, Michel Godet began conducting scenario planning. His methodology was extended at the Conservatoire Nationale des Arts et Métiers with the support of several sponsors. Godet’s work is based on the use of “perspective,” advocated by the French philosopher Gaston Berger (Ringland, 1998). Godet’s approach began by dividing scenarios into two categories: situational scenarios, which describe future situations; and development scenarios, which describe a sequence of events that lead to a future situation (Georgantzas & Acar, 1995). Godet also identifies three types of scenarios that may exist in either category: trend-based scenarios follow what is most likely, contrasted scenarios explore purposefully extreme themes, and horizon/normative scenarios examine the feasibility of a desirable future by working backward from the future to the present. Godet’s approach has evolved and now includes several computer-based tools that help highlight interdependencies between interrelated variables that may be ignored by more simple procedures (Ringland, 1998).

The French School approach is a structural analysis that is divided into three phases. Phase 1 begins the process by studying internal and external variables to create a system of interrelated elements. This approach focuses on a detailed and quantified study of the elements and compilation of data into a database. A cross-impact matrix is constructed to study the influence of each variable on the others.

Phase 2 scans the range of possibilities and reduces uncertainty through the identification of key variables and strategies. Future possibilities are listed through a set of hypotheses that may point to a trend in the data. Advanced software reduces uncertainty by estimating the subjective probabilities of different combinations of the variables.

Phase 3 is the development of the scenarios themselves. Scenarios are restricted to sets of hypotheses; and once the data have been compiled and analyzed, scenarios are built describing the route from the current situation to the future vision (Godet & Roubelat, 1996).

THE FUTURES GROUP

The Futures Group was a Connecticut-based consulting firm that developed a trend-impact analysis approach to scenario planning. This approach requires three phases: preparation, development, and reporting and utilizing (Ringland, 1998).

The preparation phase includes defining a focus, issue, or decision, and then charting the driving forces. Several questions should be answered in this phase: What possible future developments need to be probed? What variables need to be looked at for assistance in decision making? What forces and developments have the greatest ability to shape future characteristics of the organization?

The development phase includes constructing a scenario space, selecting alternative worlds to be detailed, and preparing scenario-contingent forecasts. Selecting a scenario space means examining the various future states that the drivers could produce. Illogical and nonplausible situations should be rejected. Selecting alternative worlds to be detailed involves limiting the number of future stories, since it would be impossible to explore every option. The key is to select plausible futures that will challenge current thinking. Preparing scenario-contingent forecasts is listing trends and events that would be required for the plausible future to exist. Depending on the assumptions of each alternative world, indicators are selected that might “signal” the direction in which the organization is heading.

Reporting and utilizing scenarios are covered briefly and quickly without enough detail for a user to apply. However, the futures group is one of a few approaches to even mention these activities.

DECISION STRATEGIES INTERNATIONAL

Paul Schoemaker has outlined an approach to scenario planning with many similarities to the methodology used by the Global Business Network, as might be expected since Schoemaker spent a bit of time in the planning department at Royal Dutch/Shell.

Step 1 defines the scope of the project. This includes setting a time frame, examining the past to identify rates of change, and roughly estimating the expected future rate of change. “The unstructured concerns and anxieties of managers are good places to start” (Schoemaker, 1995, p. 28).

Step 2 is to identify the key stakeholders. Obvious stakeholders include customers, suppliers, competitors, employees, shareholders, and government workers. The identification of the roles that each of these groups might play, how the roles have changed in past years, and the distribution of power according to the issue are all factors to be examined in this step.

Basic trends are identified in Step 3. The political, economic, societal, technological, legal, environmental, and industry trends are analyzed in connection with the issues from the first step. “Briefly explain the trend, including how and why it exerts its influence on your organization” (Schoemaker, 1995, p. 28). Trends can be charted in influence diagrams or matrices to help make relationships explicit. Examining trends can be useful, but remember that trends are put together by experts, and scenarios ask, “What if the experts are wrong?”

Step 4 considers the key uncertainties. What events, whose outcomes are uncertain, will significantly affect the issues of concern to the organization? A further examination of political, societal, economic, environmental, legal, and industry forces emphasizing the most uncertain elements “will reveal the most turbulent areas” (Schoemaker, 1995, p. 28). Relationships among the uncertainties should also be identified. For example, “if one economic uncertainty is ‘level of unemployment’ and the other ‘level of inflation,’ then the combination of full employment and zero inflation may be ruled out as impossible” (Schoemaker, 1995, p. 29).

Once the trends and uncertainties have been identified, initial scenario construction can begin. A simple approach is to identify extreme worlds by putting all positive elements in one and all negatives in another. Alternatively, various strings of outcomes can be clustered around high or low continuity, finding themes, or the degree of uncertainty. The most common technique is to cross the top two uncertainties of a given issue.

Step 6 checks the initial scenarios for plausibility. Schoemaker identified three tests for internal consistency, dealing with the trends, the outcome combinations, and the reactions of major stakeholders. The trends must be compatible with the chosen time frame; scenarios must combine outcomes that fit (e.g., full employment and zero inflation do not fit); and the major stakeholders must not be placed in situations they do not like but have the power to change (e.g., OPEC will not tolerate low oil prices for very long) (Schoemaker, 1995).

From the process of developing initial scenarios and checking them for plausibility, general themes should emerge. Step 7 is to develop learning scenarios by manipulating plausible outcomes. The trends may be the same in each scenario, but the outcomes, once considered plausible, can be shifted and given more or less weight in different scenarios. These scenarios “are tools for research and study rather than for decision-making” (Schoemaker, 1995, p. 29).

After constructing learning scenarios, areas that require further research are identified. These are commonly referred to as “blind spots” (Georgantzas & Acar, 1995; Schoemaker, 1995; Schwartz, 1991; van der Heijden, 1997). Companies can use these scenarios to study other industries—for example, to consider plausible outcomes of advances in multimedia and then study current research in that area.

Step 9 reexamines the internal consistencies after completing additional research. Quantitative models are commonly developed in this stage. For example, Royal Dutch/Shell has developed a model that keeps oil prices, inflation, gross national product (GNP), growth, taxes, and interest rates in plausible balances. Formal models can be used to flesh out possible secondary effects and also to serve as another check for plausibility. The models can also help to quantify the consequences of various scenarios.

Step 10 is to determine the scenarios to be used for decisions. Trends will have arisen that may or may not affect or address the real issues of the organization. Schoemaker identified four criteria for effective decision scenarios. First, scenarios must have relevance to be effective but also challenge current thinking in the organization. Second, scenarios must be internally consistent and plausible. Third, scenarios must be archetypal, or they should describe fundamentally different futures, rather than simply vary on one theme. Finally, each scenario should describe an eventual state of equilibrium. “It does an organization little good to prepare for a plausible future that will be quite short” (Schoemaker, 1995, p. 32), yet many argue that planning cycles are getting shorter.

WILSON AND RALSTON

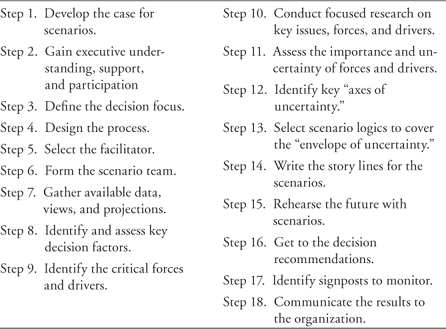

Perhaps the most detailed procedural account of scenario planning yet published, Ian Wilson and Bill Ralston based their 2006 book The Scenario-Planning Handbook on the Shell method but have made modifications throughout. Based on over fifteen years of experience as senior consultants at SRI, Ralston and Wilson have put their experience and knowledge to the test. This is a modern method that lays out an all-encompassing how-to manual for corporate executives. Wilson and Ralston’s approach is detailed in Figure 1.2.

LINDGREN AND BANDHOLD

In 2003, Mats Lindgren and Hans Bandhold published Scenario Planning: The Link between Future and Strategy. The book details their interpretation of the scenario planning process in a model they call the TAIDA method. TAIDA stands for tracking, analyzing, imaging, deciding, and acting; and the method is a simplified version of the intuitive logics approach to scenario planning, which is based on the work led by Pierre Wack and Ted Newland at Shell. The book is essentially a practitioner’s shorthand manual for exploring the basic concepts of scenario planning, with a useful appendix of methods that can be used in a variety of places throughout the scenario planning process.

FIGURE 1.2 Steps in Developing and Using Scenarios (summarized from Wilson and Ralston, 2006)

REFERENCE SCENARIOS

Ackoff (1970, 1978, 1981) identified four modes for organizations to cope with external change. Inactivity involves ignoring changes and continuing with business as usual. Reactivity waits for changes to happen and then developing a response. Preactivity involves trying to predict changes and establishing organizational position before they happen, and proactivity calls for interactive involvement with the external environment in order to “create the future for stakeholders” (Georgantzas & Acar, 1995, p. 364). Within these four modes, Ackoff uses the term reference scenario to mean the reference projections a firm would have if no significant changes occurred in the environment. Ackoff’s call for strategic turnaround starts with an idealized scenario of a desirable future. To be effective, such a scenario should be interesting and provocative—it should show what to change to evade the mess of problems in an organization’s given strategic situation.

PROCEDURAL SCENARIOS

Amara and Lipinski (1983) and Chandler and Cokle (1982) use very similar methods for constructing scenarios but prepare separate forecasts for each principal factor or variable. Chandler and Cokle (1982) “also define scenarios as the coherent pictures of different possible events in the environment whose effect on a set of businesses should be tested through linked models” (p. 132). The manipulation of macroeconomic models is a mechanism by which vague assumptions are translated into projected values of wholesale prices, gross domestic product (GDP), or consumer expenditures for an entire industry. The models used in these approaches are computer driven (Georgantzas & Acar, 1995) and provide a good example of procedural scenarios incorporating intuitive and quantitative techniques.

INDUSTRY SCENARIOS

Porter (1985) asserted that scenarios traditionally used in strategic planning have stressed macroeconomic and macropolitical issues. He further claimed that in competitive strategy the proper unit of analysis is the industry and defines industry scenarios as the primary, internally consistent views of how the world will look in the future (Porter, 1985). The essence of this view holds that there are two loops in building these industry scenarios. In this approach, industry analysis is within the larger unit of building industry scenarios. Industry-focused scenarios can help an organization in analyzing particular aspects of a business (Porter, 1985), but some have argued that beginning with a narrow focus will miss key dimensions (Wack, 1985a).

SOFT CREATIVE METHODS APPROACH

Brauers and Weber (1988) formulated an approach with three basic phases: analysis, descriptions of the future states, and synthesis. The analysis phase brings organization members to a common understanding of the problem. Based on this consensus, the problem can be further bounded and structured. Brauers and Weber recommend the use of soft creative methods for the analysis phase, including morphological analysis, brainstorming, brainwriting, and the Delphi technique. The second phase examines the possible development paths of the variables chosen in the analysis. The synthesis phase considers interdependencies among the variable factors to build different situations for the future states. These eventual scenarios are then fed through a complex computer program for linear programming and cluster analysis (Brauers & Weber, 1988).

WHERE EXISTING SCENARIO PLANNING METHODS HAVE FALLEN SHORT

This chapter has reviewed the major approaches to scenario planning available in published works. These approaches all have similarities, while some deviate largely from Pierre Wack’s original method. Important similarities among the existing methods include a technique for identifying items that could potentially shift the organization and its focus, a structured way to think about the future that introduces multiple possibilities, and a craft of innovation and creativity. However, the existing methods lack some critical elements as well. Important pieces that are not found in available work on scenario planning are

• a presentation of the theoretical foundations,

• a clear guide for how to use scenarios, and

• a detailed guide for assessing the impact of scenario projects.

CONCLUSION

This book uses the scenario planning approach developed by Pierre Wack and Ted Newland at Royal Dutch/Shell and later documented by Peter Schwartz, Kees van der Heijden, and others at the Global Business Network as its key foundation. This approach features a qualitative, “intuitive logic” way of reasoning that separates organizational issues into things that are predetermined and things that are truly uncertain. When truly uncertain forces have been isolated, energy can be spent trying to understand those forces and how they might play out across a range of possible futures. Wack’s primary goal was to shift the thinking and the mental models of managers inside Shell, and thus also the assumptions that framed their decision making. This book features an interpretation and extension of Wack’s work with a focus on performance. The foundation set by Wack and Newland at Shell is solid and effective, yet it also provides opportunities for improvement.

No doubt there are myriad other scenario planning processes based on combining various elements of those described in this chapter. The point is simply that scenario planning has been developed in practice by numerous practitioners in various kinds of organizations and parts of the world. Clarifying the approach selected for any scenario project is helpful in eliminating confusion about the philosophies, steps, and theoretical basis on which the project will be built.

The unique contributions of this book are that it presents the underlying theory and research that explain scenario planning as an effective organizational intervention, detailed descriptions of what to do with scenarios once they have been developed, and ways to assess the performance contribution of a scenario project. None of the existing texts on scenario planning provide a theoretical explanation of how scenario planning works, and none provide detailed accounts of inquiry into what the outcomes of the experience really are. Nor do any cover a variety of methods for putting scenarios to use and checking to see that they were effective. As a result, this book targets reflective practitioners, executives, and academics who want to work through complex, ambiguous problems while at the same time understand how their actions affect the issues they are facing.

This chapter has described the state of the external environment that calls for scenarios and summarized the evolution of planning in organizations. A comprehensive list of scenario planning definitions has been provided, as well as the major approaches to scenario planning. The argument for performance-based scenario planning has been made.