There is no single reason for the less-than-brilliant performance of these organizations, of course, but one limiting factor is clear. Very few managers know how to effectively tap the biggest source of performance improvement available to them—namely, the creativity and knowledge of the people who work for them.

Every day, these people see problems and opportunities that their managers do not. They are full of ideas to save money or time; increase revenue; make their jobs easier; improve productivity, quality, and the customer experience; or make their organizations better in some other way.

For more than a century, people have dabbled with various approaches to promoting employee ideas, but with little real success. In recent years, however, the picture has changed. As we shall see, companies with the best idea systems in the world now routinely implement twenty, fifty, or even a hundred ideas per person per year. As a result they perform at extraordinarily high levels and are able to consistently deliver innovative new products and services. Their customers enjoy working with them, and they are rewarding places to work.

As an example of an idea-driven organization, let us look at Brasilata, which has been consistently named as one of the most innovative companies in Brazil by the FINEP (Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos), that country’s science and development agency. Surprisingly, Brasilata is in the steel can industry, a two-hundred-year-old industry that was viewed as mature before the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957. And yet 75 percent of Brasilata’s products either are protected by patents or have been developed within the last five years. How can a company in such a mature industry be as innovative as Brazil’s more well-known and high-flying technology, aerospace, energy, cosmetics, and fashion companies? Every year, Brasilata’s nearly 1,000 “inventors” (the job titles of its front-line employees) come up with some 150,000 ideas, 90 percent of which are implemented.

Building an idea-driven organization such as Brasilata is not easy. There is a lot to know, much of which is counterintuitive. It took almost twenty years for Antonio Texeira, Brasilata’s CEO, to build the processes and culture capable of this kind of idea performance. He and his leadership team had no readily available models to follow, no classes they could attend, and no experts to call for advice. They had to figure things out as they went.

Today, there is a small but growing number of idea-driven organizations, and their collective experiences allow us to ferret out what works and what doesn’t when it comes to managing front-line ideas. This book lays out the general principles involved and describes how to methodically transform an ordinary organization into one that is idea driven. But before we get into how to do this, let us get a better sense of the power of front-line ideas by delving in some detail into another idea-driven organization—a company in Sweden whose idea system has won several national awards.

The Clarion-Stockholm is a four-star hotel located in the center of Stockholm. It routinely averages more than fifty ideas per year from each of its employees—about one idea per person per week. One reason that Clarion employees are able to come up with so many ideas is that they have been trained to look for problems and opportunities to improve. For example, every time a guest complains, asks a question, or seems confused, staff members do all they can to fully understand the issue. If staffers have an idea to address the issue, they enter it into a special computer application. If not, they enter just the raw problem. Each department has a weekly idea meeting to review its ideas and problems, and decide on the actions it wants to take on each of them.

We met with several bartenders and went through all of their department’s ideas from a randomly selected month. A sample of them is listed in Table 1.1.

As you read through these ideas, notice five things. First, the ideas are responding to problems and opportunities that are easily seen by the bar staff, but not so readily by their managers. How would the managers know that customers are asking for organic cocktails (Tess’s idea) or vitamin shots (Fredrik’s idea), or that the bartenders could serve more beer if an extra beer tap were added (Marin’s idea)? Such insights come much more easily to employees who are serving the customers directly.

Second, most of the ideas are small and straightforward. They don’t require much work to analyze and are inexpensive to implement. How difficult is it for the conference sales department to give the bartenders a “heads-up” that it will be meeting in the bar with a customer who is considering booking a major event (Nadia’s idea)? And how hard is it to increase the font size of the print on coupons given to conference participants so as to clarify what they mean (Marco’s idea) or to give the restaurant staff a tasting of the new bar cocktails so they can sell them more effectively to their diners (Tim’s idea)?

Marco

|

Get maintenance to drill three holes in the floor behind the bar and install pipes so bartenders can drop bottles directly into the recycling bins in the basement.

|

Reza

|

When things are slow in the bar, mix drinks at the tables so the guests get a show.

|

Nadia

|

Many customers ask if we serve afternoon tea. Currently, there is no hotel in the entire south of Stockholm that does. I suggest we start doing this.

|

Tess

|

Have an organic cocktail. Customers often ask for them, and we don’t offer one.

|

Nadia

|

Clarion conference and event sales staff often meet prospective customers in the bar. Give the bar staff information in advance about the prospects so they can be on alert and do something special.

|

Tim

|

Whenever the bar introduces a new cocktail, have a tasting for the restaurant staff, just as the restaurant always does when a new menu or menu item is introduced, so servers know what they are selling.

|

Fredrik

|

When the bar opens at 9:30 in the morning, many guests ask for vitamin shots (special blends of fruit juices). Put these on the menu.

|

Nadia

|

Have maintenance build some shelves in an unused area in the staff access corridor behind the bar for glasses. Currently, there is so little space for glasses in the bar that they are stored upstairs in the kitchen, and it takes 30 minutes, several times a night, for one of the two bartenders to go and get glasses, which means lost sales.

|

Marco

|

In the upstairs bar, we have to spend an hour bringing up all the alcohol from downstairs when we open and putting it away when we close. We wouldn’t have to do this if locks were installed on the cabinets in the bar.

|

Marin

|

On our receipts, when guests pay with Eurocard, it says “Euro.” This confuses many guests, who think they have been charged in euros instead of kronor. Get the accounting department to contact our Eurocard provider to see if we can change the header on the receipts.

|

Nadia

|

The bartending staff often act as concierges, telling people about the hotel, local shops, restaurants, and attractions, and giving directions. We have a concierge video that we show on our website. Offer this on the TVs in all hotel rooms.

|

Tess

|

Currently we close at 10 p.m. on Sundays, and many guests complain about this. Because we have a red dot on our liquor license from a single violation many years ago, we must have four security guards in the bar to be open after 10 on Sundays, and this is too expensive. Apply to have red dot removed, and then we can stay open with only one security guard.

|

Nadia

|

The late night security guards are sometimes curt and rude to the customers (the security service is subcontracted). These guards should be required to take the same “Attitude at Clarion” training that all Clarion staff take.

|

Marco

|

Increase the font size and make clearer that the coupons that conferences give out are for discounts at the bar, not for free drinks.

|

Nadia

|

Have the kitchen mark the prewrapped ham sandwiches that the bar sells. Bar staff currently have to cut them in half to tell the difference between them and the ham-and-cheese sandwiches.

|

Marin

|

Put an extra beer tap in the bar, so we can sell more beer. Currently, there is only one, and it is a bottleneck.

|

Nadia

|

Have maintenance put some sandpaper safety strips on the handicapped ramp in the bar. Children currently use it as a slide, and the bar staff has to deal with minor scrapes and cuts on a daily basis.

|

Nadia

|

Give the bar staff information about how many guests are staying in the hotel, so they can stock and staff the bar appropriately.

|

Third, the ideas are neither scattershot nor self-serving. They systematically drive performance improvement in key strategic areas for the hotel. They improve customer service, increase productivity, and make the bar a better place to work—in many cases doing all three at the same time. Before Marco’s idea to drill three holes for tubes through the floor to allow the bar staff to drop recyclable cans and bottles directly into bins in the basement, once an hour a bartender had to lug a plastic tub of empties down long hallways and a flight of stairs to the basement, and then separate them into three different bins. This chore took a bartender away from serving customers for roughly ten minutes. One bartender commented that whenever one of them left the bar during a busy period to empty the recyclables tub, “You could watch sales go down.” As their ideas free up time from unpleasant and non-value-adding work, the bartenders can do more for the customers, such as giving them a show at their tables when they order special mixed drinks (Reza’s idea). And imagine how much more the upstairs bartenders look forward to their work when they do not have to begin their day by lugging the entire bar stock upstairs, and finish it by returning the bar stock to the special locked storeroom downstairs (Marco’s idea). Making the hotel a better place for staff to work also affects the way they interact with their customers.

Fourth, these ideas pick up on important but intangible aspects of the bar’s operations and environment. How many customers will no longer be driven away by rude security guards or rowdy children sliding down the handicapped ramp (Nadia’s ideas)? In the hospitality industry, these intangibles often determine whether customers return or not.

Fifth, taken as a whole, the ideas illustrate the profound understanding the staff has of the bar’s capabilities and customers, an understanding that only people working on the front lines can possess.

While the list of ideas from the bar is certainly impressive, what is more impressive is that every department in the Clarion-Stockholm implements a similar list of ideas every month and has been doing so for a number of years. Each of these ideas enhances the hotel in some small way, and over time their cumulative impact is huge. This level of idea performance does not happen by accident. It takes a leadership team that (1) appreciates the power of front-line ideas to move their organization in a desired direction, (2) is willing to make them a priority, (3) aligns the hotel’s systems and policies to support them, (4) holds managers accountable for encouraging and implementing them, and (5) provides the necessary resources to run an idea-driven organization. The payoff, in this case, is a hotel capable of delivering better service at a more competitive price, a fact that is certainly noticed and appreciated by its guests. On one of our visits to Stockholm, when Sweden was feeling the impact of the global recession, we couldn’t get rooms at the Clarion. The hotel was fully booked for most of the next nine months.

Employee ideas have certainly helped the Clarion in a number of important ways. But what many leaders want to know is this: how big an impact can a good idea system really have? Just across Stockholm, we found a company that had actually measured this impact.

THE IMPACT OF FRONT-LINE IDEAS: THE 80/20 PRINCIPLE

Several years ago, Coca-Cola Stockholm was struggling with a messy problem on its half-liter Coke bottling line. After being filled and capped, the bottles would zoom around a ninety-degree corner before passing an electronic eye that would scan each bottle in order to assure that it had been properly filled. If not, an air piston would activate and push the improperly filled bottle off the line. As long as the bottles were properly spaced, the process worked quite well. Unfortunately, the bottles would sometimes bunch together as they rounded the corner. Then, when the air piston pushed a bottle into the rejection chute, the next bottle (which was in contact with the first) would be shifted slightly, sometimes causing it to hit the edge of the chute, tip over, and block the line. Ten bottles per second would then slam into the fallen bottle and Coke would fly everywhere, creating a huge mess and ruining many bottles before the operator could stop the line. This disruption to production occurred two or three times per day.

Two Six Sigma black belt project teams had failed to solve the problem, which they determined to be caused by friction between the bottles and the corner guide.

1

The teams had fiddled with many variables—the line speed, different kinds of lubricating strips along the curve guide, and the spacing of the bottles—but with little success. In the end, both teams could only come up with faster ways to clean up the mess after each incident.

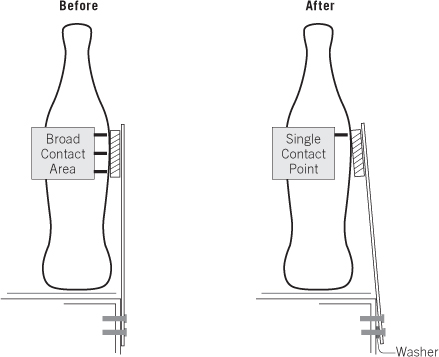

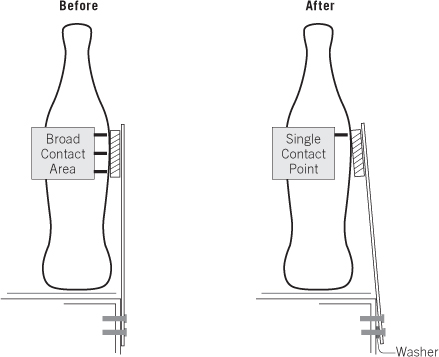

Ironically, after the black belt teams failed, the problem was solved by a simple idea from one of the bottling-line workers. His solution was to reduce the contact surface area between the guide and the bottles. By slipping a steel washer in between the guide and its mounting bracket, the guide was cocked slightly inward so that only its upper edge touched the bottle (see Figure 1.1). This lowered the friction enough to keep the bottles from bunching. The idea saved a lot of hassle cleaning up the spills, reduced downtime on the bottling line, and eliminated the need to dispose of about $15,000 worth of damaged products per year. And this was only one of 1,720 front-line ideas implemented that year.

FIGURE 1.1 Half-liter bottle idea

Interestingly, a few years before, Coca-Cola headquarters had required all corporate-owned bottlers to implement Six Sigma as a way to drive improvement. Each unit was expected to (1) train a cadre of black and green belts, (2) focus on Six Sigma improvement projects that would generate large documentable monetary savings, and (3) strive for high bottling capacity utilization. The implementation of Six Sigma on top of an effective idea system provided a rare opportunity to compare the relative impact of management-driven and front-line-driven approaches to improvement. Before joining Coca-Cola, the managing director had worked at Scania, the Swedish truck maker, which placed strong emphasis on front-line ideas. When she arrived at Coca-Cola Stockholm, one of her first actions had been to put a high-performing idea system in place. By the time the Six Sigma initiative was fully operational, the bottling unit was implementing fifteen ideas per person per year.

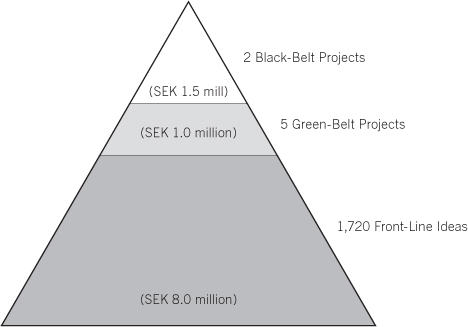

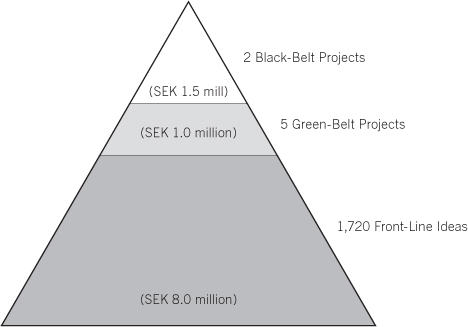

The managing director used the exhibit shown in Figure 1.2 to illustrate the relative contribution of each source of cost-saving improvements. In 2007, for example, two black belt and five green belt Six Sigma projects were completed, for savings that totaled 2.5 million Swedish kronor (SEK) (1 USD was then about 6 SEK). But the 1,720 front-line ideas generated some 8 million SEK in savings, or 76 percent of overall improvement. Armed with this insight, the company increased its emphasis on employee ideas; and in 2008, this percentage increased to 83 percent. In 2010, the company stopped tracking the cost savings from front-line ideas because the financial benefits from them were clear.

All these ideas helped Coca-Cola Stockholm surpass its peers in almost all the primary performance categories for bottling plants. Globally, it ranked first in productivity, quality, safety, environmental performance, and customer fulfillment rate. The only key metric in which Stockholm was not the top performer was capacity utilization. Standing in the mid–60 percent utilization range, its rank on this metric was merely average. The managing director told us that this was because the large number of front-line improvement ideas was constantly increasing her bottling capacity.

The Coca-Cola improvement data reflect what we have come to call the 80/20 Principle of Improvement: roughly 80 percent of an organization’s performance improvement potential lies in front-line ideas, and only 20 percent in management-driven initiatives.

FIGURE 1.2 Coca-Cola Stockholm improvement results

Managers can find it very difficult to accept the fact that front-line ideas offer four times the improvement potential of their own. But we have witnessed many examples. A case in point: Several years ago, a U.S. Navy technical support base was being pushed hard to increase its levels of support, while at the same time pressure on the defense budget was forcing it to make severe cuts. The base commander saw a high-performing idea system as a way to deal with these conflicting demands and asked us for help.

During one of our early training sessions, several upper and middle managers expressed skepticism about devoting valuable leadership attention to getting front-line ideas. In the ensuing discussion, we brought up the 80/20 principle and pointed out that if the laboratory did not go after front-line ideas, it would be trying to make headway with at most 20 percent of its innovation and cost-saving capability. One of the skeptics, the base’s top improvement expert and a Lean Six Sigma Master Black Belt, suddenly got up and left the room.

He returned a short time later and reported that he had thought the 80/20 assertion was overstated, so he had left to check it against the base’s own data. While the base’s Lean Six Sigma program was intended primarily as a tool for management-driven improvement, it did allow “grass-roots” projects to be initiated by front-line staff. The Master Black Belt had pulled the data on the previous year’s projects and separated out the savings from the grassroots projects. The leadership team had budgeted $6.8 million in savings from Lean Six Sigma—$5.4 million (79.4 percent) from management-initiated projects and $1.4 million (20.6 percent) from front-line initiated projects. But the actual savings turned out to be only $1.2 million (17.6 percent) from management-initiated projects, and $5.6 million (82.4 percent) from grassroots projects—the opposite of what had been anticipated.

Ironically, when we first encountered the 80/20 phenomenon many years ago at a Dana auto parts manufacturing plant in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, we didn’t believe it, either. At the time, the three-hundred-person operation was implementing some thirty-six ideas per person per year. While we were talking with the plant manager, he casually mentioned that 80 percent of his operation’s improvement came from front-line ideas. We had already studied and worked with idea systems for over a decade by then and, even with everything we had seen, didn’t take his statement literally. To us, it was simply a self-effacing comment and a generous recognition of his front-line people. But it did get us thinking about the relative impact of front-line ideas. We started collecting data whenever we came across it, and over the years have found it to be surprisingly consistent. Across organizations in services, manufacturing, health care, and government, 80 percent of an organization’s improvement potential lies in front-line ideas.

In our experience, when leaders become convinced of the validity of the 80/20 principle, they realize what they have been missing and want a high-performing idea system in their organizations. However, they need to be careful. There is a lot more involved in getting these ideas than simply setting up an idea process and layering it onto an existing organization.

CREATING AN IDEA-DRIVEN ORGANIZATION

Over the last several decades, U.S. furniture makers have been hit hard by global competition. Low-cost foreign competitors have forced many furniture makers out of business or obliged them to source their production overseas. Today, more than 75 percent of all wood and metal furniture sold in the United States is imported. In North Carolina alone, more than two hundred furniture manufacturers have gone out of business, and fifty thousand furniture workers have lost their jobs. Yet one company in that state, Hickory Chair, did very well throughout these hard times.

After the sudden death of the company’s forty-nine-year-old president in 1996, Jay Reardon, the vice president of marketing, was asked to take over as president. His first step was to conduct a thorough analysis of the company’s situation, from which he documented a trend that had been troubling him for some time. Over the previous decade, annual unit sales (a “unit” is one piece of furniture) had dropped from 137,000 to 87,000. The main reason Hickory Chair was still in business was that it had been able to increase its prices every year to compensate for these declining unit sales. This had pushed the average unit price for its furniture from around $300 to over $900. But Hickory’s ability to continue raising prices was coming to an end. Several lower-cost competitors had recently moved into Hickory’s niche of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century reproductions and were already undercutting its prices by 20 to 25 percent.

Reardon realized that in order to survive, Hickory had to figure out how to deliver much more value to its customers. It had to significantly lower costs, improve quality, and increase its responsiveness. Reardon openly admitted that he had limited knowledge about how furniture was made, but he did know how to approach the overall challenge. He had previously worked at Milliken Corporation, a textile company that, during his time there, was implementing more than eighty ideas per employee per year.

2

After four generations of the Milliken family’s running the company in a heavily top-down manner, CEO Roger Milliken had transformed it into one driven by employee ideas, radically improving its performance in the process.

When Reardon proposed a similar transformative initiative to involve Hickory’s front-line workers in improving the company, he encountered stiff resistance from his leadership team. Furniture-making companies in the United States had a long-standing tradition of authoritarian management, and Hickory Chair was no exception. Adding further to the challenge, several of his vice presidents who had been passed over for the company’s top job when Reardon was chosen were actively undermining his initiatives.

After struggling with his management team for almost a year, Reardon decided to take his plans directly to the front lines. He assembled the entire workforce of some four hundred employees at a local community college and showed them how the company’s unit sales were dropping while its prices were going up. He explained that these trends were unsustainable and told them that he needed their help. Then he introduced his concept of an idea program.

Reardon began taking regular walks through the plant and talking with his workers. Whenever an employee approached him with a problem, Reardon made certain it was fixed. When someone pointed out to him that the supervisors were using the bathrooms in the front offices because the factory bathrooms were in such bad shape, he checked them out and immediately ordered maintenance to fix them up and keep them clean. When informed about blatant misconduct by some supervisors—who among other things were clocking in girlfriends who were not at work and giving overtime preferentially to friends—Reardon investigated the allegations and ended up firing several of them.

He also went to work on his management team. He gave several of his more recalcitrant vice presidents an option: they could be fired immediately, or they could stay on for up to six months while looking for new jobs, on condition that they not do anything to harm the company or hinder Reardon’s initiatives. Over the next couple of years, about 70 percent of his managers either were asked to leave or chose to leave because their management styles no longer meshed with an environment of highly empowered front-line workers. In the process, an entire layer of management was eliminated.

About two years after Reardon had launched his idea initiative, the rate of improvement began to slow. After reading in several books about the work of the Toyota Supplier Support Center (TSSC)—the organization Toyota set up to develop its North American suppliers—Reardon contacted it to see if it would be willing to help Hickory. Even though Hickory was not a Toyota supplier, the legendary Toyota sensei Hajime Ohba agreed to come to North Carolina for a day and see what he could do.

When Ohba arrived, Reardon and several managers led him on a tour of the plant. At one point, while they were talking, an alarm went off. The managers ignored it and continued to talk. Ohba interrupted them: “What’s that?”

“The line-stop alarm.”

Ohba walked over to the line and asked one of the employees, “Why did the line stop?”

“The drive chain was clogged with lint.”

“Why did the chain get clogged with lint?” Ohba inquired.

“We didn’t clean the lint trap out because our supervisor told us we didn’t have time. We needed to get production out.”

Ohba smiled, “Well, you have plenty of time now.”

He then turned to the managers and said, “The reason the line went down was that the supervisor prevented the operators from doing what they knew was right.”

Reardon recalled this incident as a defining moment for his managers and him. “We were like a covey of quail, standing there yapping. The alarm went off and we continued to talk. Mr. Ohba, however, went directly to the source of the problem and began pushing for a solution. The employees already knew what needed to happen. We realized that our supervisors were often just getting in the way.”

Over the next decade, Hickory Chair’s quality, responsiveness, and innovativeness improved dramatically. Hickory didn’t just survive—it thrived. Work-in-process inventory was cut more than 90 percent, and lead times went from sixteen weeks to a week and a half, allowing the company to almost entirely eliminate finished goods inventory. Several new designer furniture lines were introduced, and customization options were added to 90 percent of the company’s furniture with no increase in delivery lead time. Half of the manufacturing that Hickory had been outsourcing to Asia was brought back in house. Except for the 2008 recession, annual sales grew at double-digit rates, and profit margins increased while prices were held steady. Hickory’s return on assets (ROA) increased to almost 50 percent.

Notice that Reardon did not just set up a process for getting front-line ideas and wait for the ideas to pour in. He had a lot of things to fix, both with his people and in his organization. He needed to correct a number of serious problems that would get in the way of improvement, to recast his management team, to learn and apply the best practices in idea management, to gain the trust and respect of his front-line workers, and to train and then empower them.

WHY ARE IDEA-DRIVEN ORGANIZATIONS SO RARE?

An obvious question arises. Given that organizations like Hickory Chair have achieved extraordinary results by tapping the ideas of their front-line people, why aren’t leaders around the world falling all over themselves to do the same thing?

The answer has two parts. First, as we saw with Hickory Chair, building an idea-driven organization takes a lot of hard work. Second, trusting front-line employees to do what is best for the organization runs counter to traditional management practice.

An interesting case in point was the time we were asked to help a New England utility that was under tremendous pressure to cut costs. We began by spending several days looking at various parts of the company to learn how it worked. At one point, we found ourselves talking to a group of workers and supervisors in a regional depot where the company stored wire, poles, and equipment for repair and maintenance work. They laughed as they told us about the constant stream of ludicrous cost-cutting measures that had been coming down from above. One they found particularly comical was a recent policy aimed at reducing the inventory of transformers held in each depot. The policy mandated that each depot keep on hand no more than two transformers of each size. But even a light rainfall, the workers told us, could wipe out the stocks of the most commonly used smaller transformers, forcing the workers to install bigger more expensive ones in their place. In fact, just the previous week, they had been forced to deploy extra crews and equipment to jury-rig a brand new $500,000 transformer to replace a $2,000 one. And after the smaller transformers were ordered and received, the crews had to be sent back out, this time to take out the larger transformers and install the smaller ones.

The utility company managers undoubtedly thought their new policy was sound. And with the pressures they were under, it is easy to see how excess inventory would be a tempting target to free up much-needed operating cash and to cut costs. It is also easy to imagine how these managers reviewed the inventory of supplies at the depots and focused in on transformers, because transformers are expensive. So far, so good. Their mistake was to put their new inventory policy in place without consulting the people who understood how it would impact operations.

The new transformer policy was made at a distance, based on data that told only part of the story. But at the same time as these managers were patting themselves on the back for their cost-cutting brilliance, all they had really accomplished was to drive up the company’s operating expenses and create a great deal of stress and non-value-adding work for its line crews.

The utility managers’ actions contrast sharply with Jay Reardon’s approach to the same type of problem at Hickory Chair. He, too, looked at the data and realized that he needed to cut costs. But then he went directly to his front-line people who had the specific knowledge needed to actually do so. While the New England utility managers identified the problem, came up with a solution, and ordered its implementation, Rear-don identified the problem, shared it with his front-line people, and asked them for their ideas on how best to solve it. Instead of a command-and-control approach that was top directed and top driven, his approach was top directed but bottom driven. Reardon got the desired results. Those utility company executives did not.

The Nobel Prize–winning economist Friedrich Hayek provided insight into why the top-directed but bottom-driven approach is so much more effective.

3

He separated knowledge into two types: aggregate knowledge about the organization, and knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place. Aggregate knowledge is what top managers tend to have. It comes from dealing with high-level data and performance numbers. These numbers are derived by quantifying, simplifying, and then combining the results of all the activities that are taking place across the entire organization and outside it. Such data provide a good picture of overall performance and trends, and are needed for making strategic-level decisions and setting the organization’s direction. This was how Reardon used the data. But, as he knew, top managers generally do not have much of the other type of knowledge, because they do not see most of the details from which their aggregate information is produced. As a result, they are poorly equipped to make the many smaller decisions that actually drive the outcomes they are after. When they do make these decisions, their resulting commands give them only the illusion of control.

Managers can easily fall into the trap of believing that they know best and that their jobs are to issue orders and make certain those orders are followed. In Chapter 2, we discuss the powerful forces that cause so many people to gravitate to this command-and-control thinking as they rise up in their organizations. We then address what is needed to counteract these forces and how to develop a management team that is capable of building and leading an idea-driven organization.

REALIGNING THE ORGANIZATION FOR IDEAS

We often give participants in our seminars the following assignment: identify a bottom-up improvement or innovation in your organization, interview the people who championed it, and briefly document their stories. When the participants present their findings to the group, invariably a litany of horror stories emerges as they tell of the heroic lengths their subjects had to go to in order to overcome managerial indifference or opposition, burdensome policies and rules, uncooperative people in other departments, key players not wanting to change, and a host of other ridiculous and petty behavioral and institutional barriers. At some point in the process of listening to these stories, someone always asks, “Why are these organizations and their managers making it so difficult for their people to implement good ideas?” Bingo!

Hero stories are a recurring theme in innovation and improvement. After years of operating in a top-down manner that emphasizes control and conformance, organizations are rife with obstacles to bottom-up ideas that their champions are forced to overcome. Perhaps the most challenging part of building an idea-driven organization is realigning it for ideas—in other words, rooting out and eliminating misalignments that are impeding the flow of ideas—so the organization can move beyond the “champions battling barriers” model of innovation and improvement.

In many cases, these misalignments are problems that have subtly plagued performance for years, but they have been tolerated because their impact has been difficult to pin down. But once an idea system is in place and the volume of ideas ramps up, the impact of these misalignments becomes much clearer, and managers can no longer ignore them.

The process of realigning an organization for ideas is never ending. Initially, many misalignments will be easy to spot as even the simplest ideas experience petty implementation delays. Examples of this from organizations we have worked with include a specialty manufacturer where it was not possible for workers and supervisors to get a few dollars to test or implement small ideas, a national luxury goods retail chain where even minor improvements needed to be approved by committees or signed off on by countless managers, a European insurance company with a three-month backlog for even the smallest IT change request, and a federal agency whose IT backlog was three years!

Less obvious barriers will often emerge only as the organization becomes more sophisticated at managing ideas. For example, some of the least visible and hardest-to-correct misalignments arise from poorly conceptualized or outdated policies. Policies are an important part of running any organization, but as we shall discuss, they often have unintended consequences. They are made by people throughout the organization who are trying to deal with various situations from their own perspectives—people who don’t typically consider their policies’ impact on the flow of ideas.

Chapters 3 and 4 discuss common misalignments and how to correct them. Chapter 3 explains the mechanisms that idea-driven organizations use to focus their front-line ideas on key strategic goals. Chapter 4 is about how to realign an organization’s management systems to enable the smooth flow of ideas. An important section of this chapter is about the development of policies, where we provide a brief primer on how to make more effective policies and how to deal with bad ones. In particular, we describe in some detail the “Kill Stupid Rules” process developed by a U.S. regional bank to modify or eliminate dysfunctional policies.

EFFECTIVE IDEA PROCESSES

A few years ago, a senior vice president at a national specialty retailer decided to conduct a campaign for employee ideas in his unit. He commissioned an expensive inspirational video, staged a big high-energy launch event, and pressured his managers to go after employee ideas. Over the next two months, his people submitted more than eight hundred ideas. The campaign appeared to have been a rousing success. But five months later, after the CEO had independently invited us in to implement a companywide idea system, only six of the eight hundred ideas had been implemented. Despite this, and the fact that several of his colleagues told us that they regarded his initiative as a spectacular failure, the senior vice president remained upbeat. He didn’t understand the damage he had done. He had staked his credibility on a poorly thought-out effort that had ended up using less than 1 percent of the ideas that his people had given him. More than 90 percent of the suggesters never even received a response. It is hard to imagine how he could have more effectively undermined his people’s trust in his willingness to listen to their ideas.

That senior vice president had not realized that there was a lot more involved in managing ideas than simply collecting them. Employees were not told what kinds of ideas were important, he did not allocate any time or resources to evaluate and implement the ideas that came in, and his managers were thrown into the campaign without any proper direction or training, which left them unsure of their roles and without some of the skills they would need.

The mistakes this executive made are not unusual. Over the years, we have watched many leaders set up idea processes believing that they will be easy to get up and running. They are unaware of the existence of high-performance idea processes, let alone what is needed to develop and launch one. From the outset, their initiatives are condemned to delivering mediocre results or to failing outright.

Chapter 5 explains how high-performing idea processes work. Although all such systems share the same principles, in practice they can look quite different. Every organization is unique: each has its own culture, cast of characters, operating systems and norms, capabilities, and history. A good idea system is not a stand-alone program. It has to be designed to work in concert with a lot of other parts of the organization. Chapter 6 is a step-by-step walk through the process of designing and launching a high-performance idea system. We discuss the pitfalls and issues that often arise, and provide tactics for dealing with them.

GETTING MORE AND BETTER IDEAS

One of the authors recently had an interesting experience at a local diner. As the waitress took his drink order, she put down a paper placemat, a knife, and a fork that had a large piece of fried egg encrusted between its prongs. She glanced at the fork, then at the author, and walked away.

Had the author been eating breakfast at the Ritz-Carlton, the dirty fork would not have made it anywhere near the table. The hotel trains its employees to be sensitive to even the slightest service problem. What was not a problem for the waitress in the diner would have been a major issue at the Ritz-Carlton.

Ideas begin with problems. If people don’t see problems, they won’t be thinking about how to solve them. Thus problem sensitivity is a key driver of ideas.

When an organization starts up a high-performing idea system, there is often an early surge of ideas directed at problems that have been bothering people for a long time. But after all the obvious problems have been addressed, employees start to run out of ideas. The remedy is training—training designed to create sensitivity to new types of problems.

In Chapter 7, we describe a variety of proven methods that idea-driven organizations have used to help their people see new and different kinds of problems, so that they can come up with greater numbers of more useful ideas. Idea activators, for example, introduce people to new ways to improve their work. Idea mining is used to extract fresh perspectives from ideas that have already been proposed. These and other methods we discuss, which can be delivered in surprisingly brief training modules, allow both employees and managers to approach idea generation with a sense of abundance of improvement opportunities rather than a sense of scarcity.

IDEA SYSTEMS AND INNOVATIVENESS

A few years ago, one of our former students was promoted to vice president at a Wall Street investment bank, and was tasked with making the bank more innovative. He called us and asked, “What should I do? Where should I start?”

Many leaders struggle with those questions and end up doing a variety of generally ineffective things in the name of innovation. For the majority, their first step should be to set up a high-performance idea system. It may seem strange that a leader looking for more breakthrough innovations should make it a top priority to go after ideas from the front lines. But for a number of reasons, the ability to produce successful breakthrough products and services on a consistent basis depends on the ability to tap large numbers of smaller front-line ideas.

Several years ago, we had the opportunity to track the development of one of Brasilata’s award-winning steel cans (Brasilata is the Brazilian company discussed in the beginning of this chapter that was averaging some 150 ideas per employee). The idea for it originated with an accounting clerk when a product designer happened to show her the prototype of a new can. She commented to him that with some minor modifications it would make a handy container for several common cooking ingredients she used. Her observation was opportune, for at the time Brasilata was producing cans primarily for nonfood products, and its management was looking for products that could be used to expand its offerings in the food market.

As we were tracking how the new can had been developed, at one point we found ourselves talking with a group of production workers who were fabricating it. One of the can’s features required some particularly clever processing, which we were trying to understand.

“By the way,” we asked, “who thought of this feature?”

The question triggered a short and intense discussion in Portuguese. Then one of the workers turned to us and said, “We can’t remember who came up with that idea, us or R&D.”

We went back to the R&D department to find out. No one there could remember, either!

As this story illustrates, ideas flow freely across Brasilata. Innovation pervades every aspect of what it does. It has been able to develop sophisticated technologies that are much more flexible than commercially available alternatives—and at a fraction of their cost. All this has allowed Brasilata to generate a continuous stream of breakthrough products that its competitors cannot duplicate.

In Chapter 8, we explain the multifaceted interplay between innovation and front-line ideas, an interplay that most managers are not aware of. As a result, their organizations are far less innovative than they could be. It is ironic that the most powerful enabler of innovativeness for most organizations is the last thing their leaders would think of.