Download PDF Excerpt

Videos by Coauthors

Follow us on YouTube

Rights Information

The World Cafe

Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter

Juanita Brown (Author) | David Isaacs (Author) | World Cafe Community (Author) | Margaret Wheatley (Foreword by) | World Cafe Community (Author)

Publication date: 06/05/2005

Bestseller over 75,000+ copies sold

Filled with stories of actual Cafe dialogues in business, education, government, and community organizations across the globe, this uniquely crafted book demonstrates how the World Cafe can be adapted to any setting or culture. Examples from such varied organizations as Hewlett-Packard, American Society for Quality, the nation of Singapore, the University of Texas, and many others, demonstrate the process in action.

Along with its seven core design principles, The World Cafe offers practical tips for hosting "conversations that matter" in groups of any size- strengthening both personal relationships and people's capacity to shape the future together. THE WORLD CAFE: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter

- Introduces readers to a simple, yet powerful conversational process for thinking together and creating actionable knowledge that has been used successfully with organizations and communities on six continents

- Clearly articulates seven key World Café design principles that create the conditions for accessing collective intelligence and breakthrough thinking

- Includes actual stories from widely varied settings-such as Hewlett-Packard, American Society for Quality, the nation of Singapore, the University of Texas, and many, many others-to show the World Café process and results

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Filled with stories of actual Cafe dialogues in business, education, government, and community organizations across the globe, this uniquely crafted book demonstrates how the World Cafe can be adapted to any setting or culture. Examples from such varied organizations as Hewlett-Packard, American Society for Quality, the nation of Singapore, the University of Texas, and many others, demonstrate the process in action.

Along with its seven core design principles, The World Cafe offers practical tips for hosting "conversations that matter" in groups of any size- strengthening both personal relationships and people's capacity to shape the future together.THE WORLD CAFE: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter

- Introduces readers to a simple, yet powerful conversational process for thinking together and creating actionable knowledge that has been used successfully with organizations and communities on six continents

- Clearly articulates seven key World Café design principles that create the conditions for accessing collective intelligence and breakthrough thinking

- Includes actual stories from widely varied settings-such as Hewlett-Packard, American Society for Quality, the nation of Singapore, the University of Texas, and many, many others-to show the World Café process and results

The World Caf Community is made up of organizational and community leaders and others who are fostering conversational leadership across the globe.

--Sharif Abdullah, founder, the Commonway Institute, and author of Creating a World that Works for All

“World Café conversations are one of the best ways I know to truly enhance knowledge sharing and tap into collective intelligence. The few simple principles in this book can lead to conscious conversations with the power to change not only the individuals who participate, but also our collective future.”

--Verna Allee, author of The Knowledge Evolution and The Future of Knowledge

“The wisdom of many voices speaks from these pages! May we take seriously their invitation to call forth what has heart and meaning in our world through conversations that matter.”

--Tom Atlee, founder, The Co-Intelligence Institute, and author of The Tao of Democracy

“The capacity to see the world of the “other” sounds simple, but it is not. Yet it is the core of creating a new human history together. The World Café and this book serve as an inspiration to help make that possible.”

--Lic. Esteban Moctezuma Barragan, Mexico's former Minister of Social Development

“The prevailing wisdom is that talk is cheap and that it's a poor, timid substitute for action. This warm and inviting book demonstrates that conversation is action, because it is the wellspring from which relationships and trust are generated and informed decisions grow.”

--Thomas F. Beech, President and CEO, Fetzer Institute

“The challenge of leadership in these times of breathtaking speed and exhausting complexity is to find creative ways to embrace the future, and let go of the past. World Café dialogue provide us the opportunity to do just that.”

--Paul Borawski, Executive Director and Chief Strategic Officer, American Society for Quality

“Understanding the World Café's fascinating model of a living social system is essential for the understanding of life and leadership in human organizations.”

--Fritjof Capra, author of The Web of Life and The Hidden Connections

“The World Café couldn't be more timely. It offers inspiration and practical guidance to those who want to convene groups—even very large groups—for conversations that stimulate hope, creativity, and collective commitment.”

--Laura Chasin, founder and Director, Public Conversations Project

“This book and the stories in it offer hope for addressing complex challenges and provide methods for strengthening family and community relationships. It is truly a work of art and a very important contribution.”

--Rita Cleary, co-founder, Visions of a Better World Foundation

“World Café conversations touch the heart of what “human being” or “being human” means. By cherishing and including diverse voices, this book models the very nature of collective knowledge that is the heart of the World Café approach to dialogue.”

--Sara Cobb, Director, Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University, and former Executive Director, Program on Negotiation, Harvard Law School

INTRODUCTION Beginning the Conversation: An Invitation to the World Café

Chapter One Seeing the Invisible: Conversation Matters!

Chapter Two Conversation as a Core Process: Co-Creating Business and Social Value

Chapter Three Principle 1: Set the Context

Chapter Four Principle 2: Create Hospitable Space

Chapter Five Principle 3: Explore Questions That Matter

Chapter Six Principle 4: Encourage Everyone's Contribution

Chapter Seven Principle 5: Cross-Pollinate and Connect Diverse Perspectives

Chapter Eight Principle 6: Listen Together for Patterns, Insights, and Deeper Questions

Chapter Nine Principle 7: Harvest and Share Collective Discoveries

Chapter Ten Guiding the Café Process: The Art of Hosting

Chapter Eleven Conversational Leadership: Cultivating Collective Intelligence

Chapter Twelve The Call of Our Times: Creating a Culture of Dialogue

Epilogue How Can We Talk It Through? by Anne W. Dosher

Afterword Discovering the Magic of Collective Creativity by Peter M. Senge

Acknowledgments

Resources and Connections: The World Café

Related Resources

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ONE

Seeing the Invisible:

Conversation Matters!

It’s never enough just to tell people about some new insight.Rather, you have to get them to experience it in a way that evokes its power and possibility. Instead of pouring knowledge into people’s heads, you need to help them grind a new set of eyeglasses so they can see the world in a new way.

—John Seely Brown, Seeing Differently: Insights on Innovation

STORY

DISCOVERING THE WORLD CAFÉ: THE INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL PIONEERS

As Told By

David Isaacs

David Isaacs, my partner in life and work, is a co-originator of the World Café. In this story he shares the serendipity surrounding the birth of the World Café and its community of practice, along with our early musings about what was at play in Café dialogues. Our initial Café experience also set the stage for unexpected discoveries about the powerful role that conversation plays in shaping our futures.

January 1995. It is a very rainy dawn at our home in Mill Valley, California. A thick mist hangs over Mt. Tamalpais as I look out beyond the massive oak tree that borders the patio outside our living room. We have twenty-four people arriving in half an hour for the second day of a strategic dialogue on intellectual capital. Juanita and I are hosting the gathering in collaboration with Leif Edvinsson, vice president of intellectual capital for the Skandia Corporation in Sweden. This is the second in a series of conversations among the Intellectual Capital Pioneers—a group of corporate executives, researchers, and consultants from seven countries who are at the leading edge of this inquiry.

The field of intellectual capital and knowledge management is still in its infancy. No books have yet been written. No maps exist. We’re making them as we go. Last evening we were in the midst of exploring the question: What is the role of leadership in maximizing the value of intellectual capital?

Juanita is worried. As she sets out the breakfast and prepares the coffee, she’s concerned about how we can create the right setting for the day’s agenda if the pouring rain continues and no one can go outside on the patio to visit when they arrive. Then I have an idea. “Why don’t we set up our TV tables in the living room and just have people get their coffee and visit around the tables while we’re waiting for everyone to arrive? We’ll then put away the tables and begin with our normal dialogue circle.”

Juanita breathes a sigh of relief. As we set out the small tables and white vinyl chairs, our interactive graphics specialist, Tomi Nagai-Rothe, arrives and adds, “Those look like café tables. I think they need some tablecloths!” She improvises, draping white sheets of easel paper over each of the paired TV tables. Now it’s getting kind of playful. We’ve stopped worrying about the rain, which is coming down in sheets. Juanita decides we need flowers on the café tables, and goes for small vases downstairs. In the meantime, Tomi adds crayons to each of the tables, just like those in many neighborhood cafés. She makes a lovely sign for our front door—Welcome to the Homestead Café—playing off our address, Homestead Boulevard, which is actually a narrow road up the side of a mountain.

Just as Juanita places the flowers on the tables, folks begin to arrive. They are delighted and amused. As people get their coffee and croissants, they gather in informal groups around the café tables and begin to talk about last night’s question. People are really engaged. They begin to scribble on the tablecloths. Juanita and I have a quick huddle and decide that, rather than have a formal dialogue circle to open the gathering, we will simply encourage people to continue to share what’s bubbling up from their conversations that could shed light on the essence of the relationship between leadership and intellectual capital.

15Forty-five minutes pass and the conversation is still going strong. Charles Savage, one of our members, calls out, “I’d love to have a feel for what’s happening in the other conversations in the room. Why don’t we leave one host at the table and have our other members travel to different tables, carrying the seed ideas from our conversation and connecting and linking with the threads that are being woven at other tables?” There’s consensus that the suggestion seems like fun. After a few minutes of wrap-up, folks begin to move around the room. One host remains at each table, while the others each go to a different table to continue the conversations.

This round lasts another hour. Now the room is really alive! People are excited and engaged, almost breathless. Another person speaks up. “Why don’t we experiment by leaving a new host at the table, with the others traveling, continuing to share and link what we’re discovering?”

And so it continues. The rain falling, hard. People huddling around the TV tables, learning together, testing ideas and assumptions together, building new knowledge together, adding to each other’s diagrams and pictures and noting key words and ideas on the tablecloths. Juanita and I look up and realize that it is almost lunchtime. We have been participating in the café conversations ourselves and the hours have passed as if they were minutes.

The energy in the room is palpable. It is as if the very air is shimmering. I ask the group to wrap up their conversations and gather around a large rolled-out piece of mural paper that Tomi has placed on the rug in the middle of the living room floor. It looks, in fact, like a large café tablecloth spread on the floor. We invite each small group to put their individual tablecloths around the edges of the larger cloth and then take a “tour” to notice patterns, themes, and insights that are emerging in our midst.

As Juanita and I watch our collective discoveries and insights unfold visually on the large mural paper in the center of the group, we know something quite unusual has happened. We are bearing witness to something for which we have no language. It is as if the intelligence of a larger collective Self, beyond the individual selves in the room, had become visible to us. It feels almost like “magic”—an exciting moment of recognition of what we are discovering together that’s difficult to describe yet feels strangely familiar. The café process somehow enabled the group to access a form of collaborative intelligence that grew more potent as both ideas and people traveled from table to table, making new connections and cross-pollinating their diverse insights.

. . .

16Perspectives & Observations

After that breakthrough meeting, David and I, along with Finn Voldtofte, a close colleague from Denmark who had participated in that initial gathering, spent the next day trying to understand what had happened. We looked at each of the components of the day, examining how it had contributed to the living knowledge that emerged. We considered what had occurred when people entered the house and saw the colorful and inviting Homestead Café in our living room. Was there something about the café itself as an archetype—a familiar cultural form around the world—that was able to evoke the immediate intimacy and collective engagement that we experienced? Did the positive associations that most people make with cafés support the natural emergence of easy and authentic conversation that had happened, despite the lack of formal guidelines or dialogue training among the participants?

We considered the role and use of questions to engage collaborative thinking. Was there something in the way we had framed the conversation around a core question that participants cared about—“What is the relationship between leadership and intellectual capital?”—that affected the quality and depth of collective insight? Then there was the cross-pollination of ideas across groups. Did carrying insights from one group to another enable the emergence of an unexpected web of lively new connections among diverse perspectives? We mused on the function of people writing on their tablecloths and later contributing their collective insights to the common tablecloth as we explored our discoveries together. What was the importance, if any, that people could literally see each other’s ideas on their tablecloths, similar to a hurried sketch or an idea scribbled on a napkin?

As we tried to illuminate our experience, we were reminded of how many new ideas and social innovations have historically been born and spread through informal conversations in cafés, salons, churches, and living rooms. We realized that what we had experienced in the café conversation in our living room was perhaps a small-scale replica of a deeper living pattern of how knowledge-sharing, change, and innovation have always occurred in human societies. We recalled the salon movement that gave birth to the French Revolution, as well as the sewing circles and committees of correspondence that foretold America’s independence. Finn reminded us of the widespread network of study circles that fostered the social and economic renaissance in Scandinavia during the early twentieth century, and we realized that David’s and my early experiences with social movements, including the farmworkers, followed the same pattern of development. Founders of major change efforts often say, “Well, it all began when some friends and I started talking.”

17The evolving web of conversations in our living room seemed to allow us to experience directly the often invisible way that large-scale organizational and societal change occurs—what we have since come to call “nature’s strategic planning process.” Are we as human beings so immersed in conversation that, like fish in water, conversation is our medium for survival and we just can’t see it? Had we somehow stumbled onto a set of principles that made it easier for larger groups to notice and access this natural process in order to develop collaborative intelligence around critical questions and concerns? Might this awareness support leaders in becoming more intentional about fostering connected networks of conversation focused on their organization’s most important questions?

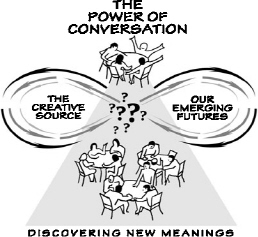

Out of this conversation, the image of the World Café emerged as a central metaphor to guide our nascent exploration into the possibilities that we had tapped into that rainy day. Many of us who were at that initial gathering began to experiment with the simple process that we had discovered. We began to host World Café conversations in a variety of settings and to share our learnings with each other as we went.

And then from a completely unexpected source, it became clear to me just how much conversation matters. It matters a lot.

Knowing Together and Bringing Forth a World

I was serving as co-faculty for a living systems seminar sponsored by the Berkana Institute, which supports new forms of leadership around the world. Fritjof Capra, the noted physicist and living systems theorist, who was also on the faculty, was giving a talk about the nature of knowledge. In his measured, professorial style, Fritjof began to share surprising ideas from the work of two Chilean scientists—evolutionary biologist, Humberto Maturana, and cognitive scientist, Francisco Varela. I won’t be able to do full justice to the range and subtlety of their groundbreaking research, but I’d like to share one key aspect of it with you because I think it has direct relevance for how people see the world and how we choose to live in it.

Maturana and Varela’s work reaffirms that as a species we humans have evolved the unique capacity for talking together and for making distinctions of meaning in language. This human gift for living in the braided meanings and emotions that arise through our conversations is what enables us to share our ideas, images, intentions, and discoveries with each other. Since our earliest ancestors gathered in circles around the warmth of a fire, conversation has been our primary means for discovering what we care about, sharing knowledge, imagining the future, and acting together to both survive and thrive.

People in small groups spread their insights to larger groups, carrying the seed ideas for new conversations, creative possibilities, and collective action. This systemic process is embodied in self-reinforcing, meaning-making networks that arise through the interactions that conversation makes possible. Maturana and Varela point out that because we live in language—and in the sophisticated coordination of actions that language makes possible— we “bring forth a world” through the networks of conversation in which we participate (1987, p. 234). We embody and share our knowledge through conversation. From this perspective, conversations are action—the very lifeblood and heartbeat of social systems like organizations, communities, and societies. As new meanings and the coordinated actions based on them begin to spread through wider networks, the future comes into being. However, these futures can take many alternative paths. In a provocative seminar that Maturana later gave at the Society for Organizational Learning, he brought this message home:

19All that we humans do, we do in conversation. . . . As we live in conversation new kinds of objects continue to appear, and as we take these objects and live with them, new domains of existence appear! So here we are now, living with these very funny kinds of objects called firms, companies, profit, incomes, and so on. And we are very attached to them. . . . Just the same, we are not necessarily stuck in any of the objects we create. What is peculiar to human beings is that we can reflect and say, “Oh, I’m not interested in this any more,” change our orientation, and begin a new history. Other animals cannot reflect, as they do not live in language. We are the ones who make language and conversation our manner of living. . . . We enjoy it, we caress each other in language. We can also hurt each other in language. We can open spaces or restrict them in conversations. This is central to us. And we shape our own path, as do all living systems (Maturana and Bunnell, 1999, p. 12).

Thus, from the perspective of human evolution, conversation is not something trivial that we engage in among many other activities. Conversation is the core process by which we humans think and coordinate our actions together. The living process of conversation lies at the heart of collective learning and co-evolution in human affairs. Conversation is our human way of creating and sustaining—or transforming—the realities in which we live.

Vicki Robin, my dear friend and colleague, is the founder of Conversation Cafés, an innovative small group dialogue approach that invites citizens to gather in cafés and other public places to explore key societal questions. Recently, she shared with me a vivid reflection of how this often invisible process works in everyday life.

20We talk to ourselves in our minds about our past, present, and future. Out of this self-talk, we talk with others about our pasts, present, and futures, generating personal and shared possibilities though lively exchanges of ideas and feelings. We each then carry the meanings and possibilities we’ve created into other conversations at home, at work, at church, in boardrooms, and bedrooms, and halls of power everywhere. A daughter talks to her father about her concerns for the future . . . and company policy changes. A father talks to his daughter about his concerns for her future . . . and a new life path unfolds, later impacting thousands. Line workers talk with their bosses . . . and a plant is redesigned. Citizens testify at public hearings . . . and new priorities for society emerge. We speak our world into being. A buzz develops—a kind of overtone of resonant ideas carried through multiple conversations— that tells us what’s on our collective mind. Some among us put words on this buzz and new possibilities for us as a whole begin to enter our language, the vehicle of meaning-making. We see ourselves in their descriptions—“Ah,” we think, “I never saw that, but yes, that is true.” We talk about it . . . shaping again what we collectively imagine for ourselves.Our conversations shape the spirit and substance of our times.

Another colleague shared with me a wonderful story that provides a powerful example of the way we can shape the future through conversation. The story began with a dinner conversation among four friends over steak and Chianti at the home of a young businesswoman in Munich and evolved, in just a few weeks, into one of the largest mass movements in Germany since the end of World War II.

Over dinner, the four friends decided it was time for them to step out from the “silent majority” and show their repudiation of the rising number of neo-Nazi attacks on foreigners. By the time dessert was over, each agreed to call several friends and colleagues and share the idea of creating a silent candlelight vigil to bear witness to these injustices. Their first gathering drew one hundred friends to a popular downtown bar, each of whom agreed to call ten others to encourage a larger turnout for a second event. Within days the “candlelight conversation” spread across the city through circles of acquaintances in businesses, schools, churches, and civic groups. The original group of friends—and the nation as a whole—were stunned when four hundred thousand people turned out in Munich for the vigil.

21Inspired by the Munich gathering, citizens in other cities held conversations and created vigils over the following weeks. Over five hundred thousand turned out in Hamburg, two hundred thousand in Berlin, and one hundred thousand or more in Frankfurt, Nuremberg, and other cities. Many smaller towns joined in what became a national dialogue on the acceptability of neo-Nazi behavior. The seemingly endless chains of flickering candlelight became a powerful symbol of the nation’s collective commitment, born in conversation, to turn the tide against such behavior (Kinsler, 1992). And this happened prior to widespread use of the Internet!

Conversation as a Generative Force

I was excited to discover Maturana and Varela’s work on the power of conversation to shape our future and to encounter vivid examples of this power in action. For the first time, I could see that leading edge thinkers with backgrounds completely different from our own were discovering what David and I had intuitively sensed from our lived experience with social movements as well as with our early World Café experiments. As we looked at the picture painted by both scholars and practitioners in other fields of endeavor, a fascinating pattern began to emerge. Although their perspectives on the importance of conversation may have made up only a single piece in the larger puzzle each was exploring in his or her own work, when taken together these insights began to reveal the critical role of conversation in shaping our lives. I’d like to share a collage of these ideas to give you a flavor of what we noticed as we literally put the pieces together on a large wallboard. Please take a few minutes to read carefully, on the following pages, what these thought leaders from different fields have to say. I think you’ll find their ideas illuminating.

CONVERSATION MATTERS!

Learning Organizations

True learning organizations are a space for generative conversations and concerted action which creates a field of alignment that produces tremendous power to invent new realities in conversation and to bring about these new realities in action.

Fred Kofman and Peter Senge

“Communities of Commitment”

Organizational Dynamics

Politics

Democracy begins in human conversation. The simplest, least threatening investment any citizen can make in democratic renewal is to begin talking with other people, asking the questions and knowing that their answers matter.

William Greider

Who Will Tell the People?

Strategy

Strategizing depends on creating a rich and complex web of conversations that cuts across previously isolated knowledge sets and creates new and unexpected combinations of insight.

Gary Hamel

“The Search for Strategy”

Fortune

Information Technology

Technology is putting a sharper, more urgent point on the importance of conversations. Conversations are moving faster, touching more people, and bridging greater distances. These networked conversations are enabling powerful new forms of social organization and knowledge exchange to occur.

Rick Levine and others

The Cluetrain Manifesto

Education

Within communities that foster human growth and development, change seems to be a natural result of constructing meaning and knowledge together—an outgrowth of our conversations about what matters. Leaders need to pose the questions and convene the conversations that invite others to become involved. . . . In social systems such as schools and districts, one good conversation can shift the direction of change forever.

Linda Lambert and others

The Constructivist Leader

The Knowledge Economy

Conversations are the way workers discover what they know, share it with their colleagues, and in the process create new knowledge for the organization. In the new economy, conversations are the most important form of work . . . so much so that the conversation is the organization.

Alan Webber

“What’s So New About

the New Economy?”

Harvard Business Review

Family Therapy

Our capacity for change lies in “the circle of the unexpressed,” in the capacity we have to be “in language” with each other and, in language to develop new themes, new narratives, and new stories. Through this process we co-create and co-develop our systemic realities.

Harlene Anderson and Harold Goolishian

“Human Systems as Linguistic Systems”

Family Process

Leadership

Talk is key to the executive’s work . . . the use of language to shape new possibilities, reframe old perspectives, and excite new commitments . . . the active process of dialogue, and the caring for relationships as the core foundation of any social system.

Suresh Srivastva and David Cooperrider

Appreciative Management and Leadership

Collective Intelligence

Dialogue is the central aspect of co-intelligence. We can only generate higher levels of intelligence among us if we are doing some high quality talking with one another.

Tom Atlee, Co-Intelligence Institute

The Tao of Democracy

Conflict Resolution, Global Affairs

The reality today is that we are all interdependent and have to coexist on this small planet. Therefore, the only sensible and intelligent way of resolving differences and clashes of interests, whether between individuals or nations, is through dialogue.

His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

“Forum 2000” Conference, Prague

Executive Development

As the new business landscape continues to emerge, and new forms of organization take shape, our ability to lead will be dependent upon our ability to host and convene quality conversations.

Robert Lengel, Ph.D., Director

Center for Professional Excellence

University of Texas at San Antonio

Executive MBA Program

Futures Research

Conversation is the heart of the new inquiry. It is perhaps the core human skill for dealing with the tremendous challenges we face. The culture of conversation is a different culture, one that can make a difference to the future of the world. If we combine conversations that really matter . . . with the interactive reach of the Internet, we have a powerful force for change from the ground up.

Institute for the Future

In Good Company:

Innovation at the Intersection of

Technology and Sustainability

Consciousness Studies

I’m suggesting that there is the possibility for a transformation of the nature of consciousness, both individually and collectively, and that whether this can be solved culturally and socially depends on dialogue. That’s what we’re exploring.

David Bohm, On

Evolutionary Biology

Our human existence is one in which we can live whatever world we bring about in our conversations, even if it is a world that finally destroys us as the kind of being that we are. Indeed, this has been our history since our origins as languaging beings—namely, a history or creation of new domains of existence as different networks of conversation.

Humberto Maturana and Gerda Verden-Zöller

The Origin of Humanness in the Biology of Love

What We View Determines What We Do

What if you began to shift your lens to see the power and potential of the conversations occurring in your own family, organization, community, or nation? What if you believed and acted as if your conversations and those of others really mattered? What difference would that make to your daily choices as a parent, teacher, line leader, meeting planner, organizational specialist, community member, or diplomat?

As Maturana and Varela point out, we live inside the images we hold of the world. It can be disturbing to “see differently” and to contemplate the practical implications of changing our lenses (Lakoff, 2003; Morgan, 1997). Yet as Noel Tichy, head of the University of Michigan’s Global Leadership Program, told me many years ago, “What we view determines what we do.” How we view the world around us, and how we act based on those images, can make all the difference.

As we enter a time in which the capacity for thinking together and creating innovative solutions is viewed as critical to creating both business and social value, many of us still live with the idea that “talk is cheap,” that most people are “all talk and no action,” and that we should “stop talking and get to work.” Lynne Twist, a social entrepreneur who has raised millions for improving life in developing nations, has a different perspective—one that you might want to play with as you read the stories and reflections that follow. “I believe,” she said, “that we don’t really live in the world. We live in the conversation we have about the world. . . . And over that we have absolute, omnipotent power. We have the opportunity to shape that conversation, and in so doing, to shape history” (Toms, 2002, pp. 38–39). As your host I invite you, just for the time you are reading this book, to put on a new set of glasses. See with new eyes the conversational landscape that has been here all along awaiting our personal attention and care. And begin to live a different future.

Questions for Reflection

Consider the conversations you are currently having in your family, your organization, or your community. To what degree do they create frustration and fragment efforts or offer new insights and ways to work collectively?

If you were to accept the perspective that conversation really is a core process for accessing collective intelligence and co-evolving the future, what practical difference would that make in how you approached conversations, particularly in situations you care about?

Pick one upcoming conversation that matters in your own life or work. What one specific thing might you do or what one choice might you make that would improve the quality of that conversation?