Download PDF Excerpt

Videos by Coauthors

Follow us on YouTube

Rights Information

Terms of Engagement 2nd Edition

New Ways of Leading and Changing Organizations

Dick Axelrod (Author) | Richard Axelrod (Author)

Publication date: 09/07/2010

Bestseller over 25,000+ copies sold

Find out more about our Bulk Buyer Program

- 10-49: 20% discount

- 50-99: 35% discount

- 100-999: 38% discount

- 1000-1999: 40% discount

- 2000+ Contact ( bookorders@bkpub.com )

Dick Axelrod is a cofounder of the Axelrod Group Inc., a consulting firm that pioneered the use of employee involvement to effect large-scale organizational change. His clients include Boeing, British Airways, Chicago Public Schools, Calgary Health Authority, Coca-Cola, Harley-Davidson, Hewlett-Packard, Novartis, and the UK s National Health Service.

CHAPTER 1

Why Change Management Needs Changing

That. didn’t work. Let’s do it again.”

In organizations around the world, this is how change happens. You, the organization’s leader, identify a problem and hire an expert consulting organization to create the solution. The consultants bring in their legions and you get your answer. Next, you try to sell the plan to the rest of the organization. But instead of excitement, you’re met with indifference and resistance. Getting people on board becomes a full-time obsession. Your elegant solution, wrapped in a handsome binder, sits in silence on your bookshelf, an expensive reminder of what might have been.

“That still didn’t work. Let’s tweak the model.”

This cycle has repeated often. To deal with the apathy and resistance that accompanies many change processes, consultants developed a change management structure to ensure buy-in. This structure consists of a sponsor group, a steering committee, and design teams representing a cross section of the organization. This streamlined organization strives to reduce the barriers to change that exist within the wider organization. But these groups and teams often fall into the same trap that exists when consultants work solely with leaders. They go on to create the solution, and then, after making all of the key decisions, they seek to create buy-in from the rest of the organization.

Whether you are developing a strategic plan, improving a process, or redesigning an organization, the process is the same. This way of working is so ingrained that few question it.

THE DETROIT EDISON STORY, PART 1—WHAT NOT TO DO

For over a year, Detroit Edison managers had been working to improve their supply-chain process. They were following the acknowledged best change management practice, complete with a sponsoring group, a steering committee, and a set of commodity teams, along with an army of expert consultants from one of the big four consulting firms. Despite the hard work of many people from inside and outside the organization, they had little to show for it: lots of good ideas, none of them implemented. The lack of progress frustrated the sponsors, the steering committee, and the commodity teams—they just could not understand why they could not get the organization to support the changes they were proposing.

In spite of its critical importance to the organization, most people greeted the supply-chain improvement process with yawns. The only ones who seemed to care were members of the various committees—and even they were starting to show signs of disillusionment.

Fortunately, this story has a successful conclusion. The next installment—in chapter 2—describes how Detroit Edison abandoned the old change management approach to supply-chain improvement in favor of the new change management with dramatic results.

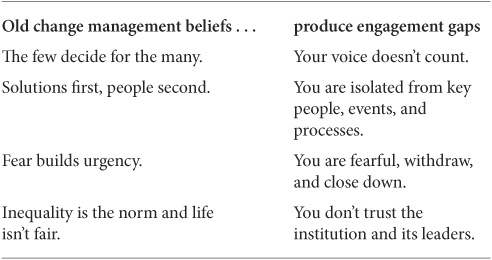

Four beliefs are at the core of the old change management:

• The few decide for the many. The change process works best when a select few—that is, leaders, consultants, and members of the sponsor team, steering committee, and design teams—decide what should be done. Populating these groups with the best and the brightest ensures success. This multilevel, cross-functional structure puts all key decision makers in the room. As a result, people within the organization will feel represented.

• Solutions first, people second. Because getting the right answer is crucial, developing the plan becomes everyone’s focus. The groups work hard, often in isolation because they don’t want to be distracted from the task at hand, to develop strategies, redesign organizations, and develop new cultures. While giving a nod to participation, they believe the best approach is to focus on the solution first and people second. The prudent course is to make the important decisions first and then move to widespread participation.

• Fear builds urgency. The best way to motivate people is to alarm them. A sense of urgency occurs when you light a fire under people, thereby creating a “burning platform.” When people are concerned about their jobs or their future, they take action. Nothing of consequence ever happens without a burning platform.

• Inequality is the norm and life isn’t fair. At an early age we learned life isn’t fair and not to expect equity in our dealings with others. The title of Harold Kushner’s book When Bad Things Happen to Good People. says it all. Because life is capricious, we must constantly be on guard. It’s a mean world out there; do not expect equity or to be treated fairly. As the saying goes, no good deed goes unpunished.

THE ENGAGEMENT GAP

These four beliefs combine to increase the engagement gap that naturally occurs in any change process. Any change initiative necessarily begins with a group of people who initially grasp the need for change. At this point, an engagement gap opens between those who want change to occur and the rest of the organization.

The old change management seeks to address this problem by creating sponsor groups, steering committees, and design teams. The problem is that as these groups immerse themselves in their work, the engagement gap widens between those who are part of the instigating groups and everyone else. Increasingly, these groups tend to objectify those not involved in the process as resisters and isolate themselves from the rest of the organization, fearing that time spent away from their work will cause delays.

As the engagement gap widens, resistance increases. This engagement gap, first identified by Peter Senge and others (1999), is an inescapable part of organizational change. No change effort can succeed for long in the face of an everwidening engagement gap. Consequently, success depends on narrowing, rather than widening, the engagement gap. Why, under current change management practices, does the engagement gap widen?

Your Voice Doesn’t Count

Whenever a change initiative is structured around a small group (representative or not) that designs and develops the overall change process, there is a risk of widening the engagement gap. The smaller the group and the less open the members are to soliciting input from the larger system, the greater the risk. When the gap widens, people come to believe that their voices do not count.

In such cases, people commonly resist plans in which they weren’t included and, as a result, don’t feel any real ownership. Or they have concerns about the decisions reached but feel blamed if they raise their concerns. Or they feel they have no choice but to accept the inevitable.

Excluded from the planning process, the “opportunity” occurs to decide how to implement plans. This typically does not feel like an opportunity at all but more like a manipulation. Is it any wonder that this process increases resistance rather than reduces it? When people are excluded from the planning process, the only opportunity they have is to implement the plans.

You Are Isolated from Key People, Events, and Processes

The old change management committee structure isolates leaders and organization members from one another, thus further increasing the engagement gap. The top of the organization has one view of the world, the middle levels another, and the lower levels a still different view. And customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders add another dimension. Instead of working together to bring their combined knowledge to bear on an issue, these groups work separately on their own discrete parts.

Here is a scenario I have witnessed repeatedly that demonstrates the problems of isolating leaders and organization members from each other. The design team works feverishly to develop a set of proposals. It then spends as much time preparing for their presentation to the steering committee as it did developing its proposals because the team knows how important it is to present the ideas well. At the steering committee meeting, the committee members put design team members on the hot seat. Soon everyone becomes defensive. Steering committee members, usually midlevel managers and union officials, feel that they are raising legitimate concerns based on their understanding of the organization.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU |

Relegating leaders to the role of sponsors is a significant flaw. In this role, leaders are frequently isolated. This prevents them from contributing valuable knowledge, expertise, and insights to the design teams that make up the parallel organization. The only time they can contribute is when they review plans for approval. |

On the other hand, design team members begin to believe that the steering committee has already determined the answer it wants. The design team goes back and tries to give the steering committee what it wants while staying true to its own beliefs. The steering committee waits for the next report, not quite understanding why the design team members are so defensive. After a number of iterations of this process, the steering committee arrives at a decision it can support. Then the process repeats itself when the steering committee members review the proposed changes with the sponsor group.

You Are Fearful, Withdraw, and Close Down

The inability to develop critical support for necessary changes results from the decision to use fear as a motivator. We have all seen what occurs when widespread organizational fear takes over. People shut down. They stop working. Instead of focusing on improving the organization, they focus on self-preservation.

You Don’t Trust the Institution and Its Leaders

When leaders believe inequality is the norm and life isn’t fair, their actions often produce a lack of trust. Because people in the organization come to believe that fairness is not present, they distrust leadership’s motives, and any change process the leaders initiate is doomed before it starts.

TELEPHONE COMPANY’S BREAKTHROUGH FAILS TO BREAK THROUGH: WHY? |

Consider a telephone company’s recent experience. The change management committees created a brilliant design for a new organization aligned with its customer base: they replaced the previous organizational silos with integrated business units. Both the sponsors and the committee members believed that they had created a breakthrough for this stodgy old organization. |

Yet paralysis gripped the organization. Why? For more than a year, the design group had made decisions behind closed doors. Although the design group actively solicited opinions, not all departments and levels of people felt included in the process. When the time came to roll out the new organization, there had been so many rumors that people were negatively disposed toward it. |

In the end, the design group could not bridge the gap to the new organization, with its greater responsiveness to customers and increased collaboration and teamwork. From the very beginning, people believed that fairness was absent. So they rejected ideas that would benefit them and the organization. |

A NEUROSCIENCE VIEW OF THE OLD CHANGE

MANAGEMENT

Neuroscience helps explain how the old change management actually works against creative problem solving. Simply put, there are two human responses: we move away from threats and we move toward rewards. When the threat response in the brain kicks in, creativity and innovation decrease. When the reward response in the brain kicks in, creativity and innovation increase.

According to David Rock, author of Your Brain at Work, “Engagement is a strong reward state . . . Rewards activate the reward circuitry of the brain that increases dopamine levels in your pre-frontal cortex, decreases cortisone levels. It literally makes it easier to make connections, makes it easier to learn, makes you more optimistic, helps you see solutions, helps you find alternatives for action . . . So when you get an increase of dopamine in your pre-frontal region, you have essentially much better decision-making and problem solving, emotional regulation, collaboration, and learning” (D. Rock, pers. comm., December 22, 2009).

TABLE 1.1

HOW THE OLD CHANGE MANAGEMENT PRODUCES ENGAGEMENT GAPS

Rock (2009) has developed the SCARF (Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness) model to identify those factors that influence the reward response. When you apply the SCARF model to the old change management, it is easy to see how

• Status fades away when the few decide for the many. Status is about your relative importance to others. It’s difficult to feel important when you know your voice doesn’t count.

• Certainty diminishes when you are isolated from key people, events, and processes. You just don’t know what is going on and you end up feeling more threatened.

• Autonomy shrinks when you don’t feel you can influence your own situation. A feeling of helplessness sets in, fear takes over, and you withdraw and close down.

• Relatedness decreases as leaders and organizational members become isolated from each other at the very time you need connections between people.

• Fairness lessens when the change process appears to ignore evenhandedness. Self-interest takes over when you need people to look out for the good of the whole.

KEY POINTS

The old change management works against innovation and creativity.

The old change management works against innovation and creativity.

When people do not have a voice in change that affects them, they will resist even if the change benefits them.

When people do not have a voice in change that affects them, they will resist even if the change benefits them.

Engagement gaps increase when

Engagement gaps increase when

• You believe that your voice does not count.

• You are isolated from key people, events, and processes.

• You are fearful.

• You don’t trust the institution and its leaders.

QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION

What are your own beliefs about organizational change?

What are your own beliefs about organizational change?

To what extent do a lack of voice, isolation, fear, and low trust exist in your organization? What are the causes?

To what extent do a lack of voice, isolation, fear, and low trust exist in your organization? What are the causes?

What are the upsides and downsides for you and your organization to continue using the old change management?

What are the upsides and downsides for you and your organization to continue using the old change management?